~ Americana Harmony ~ 'that simultaneous occurrence of musical tones' '... streamlining the process of learning our harmonic spectrum of colors with basic nuts and bolts theory and movable shapes ...' |

Americana harmony nutshell. How lucky for all musicians, and fret players especially, to have such a system of tuned up pitches to make harmony right under our fingertips in the piano. Mathematically built right into the necks of our guitars, with strings over frets we really get the best of both; a flexibility in tuning ancient single note melody pitches by various bendings and vibratos and the modern 17th century pitches of super precision, often termed as the 'equal temper' tuned pitches, which are stackable into any chord imaginable. Imagine that :) |

For in our Americana musics we can express with single notes ideas that lean towards the pitches of the natural tuned scale and its Americana pure blue hue, while we can also have supportive bass line and the chords, whose stacked pitches require a high precision of tuning to properly (aurally in tune) function through all 12 paired key centers simultaneously. This gives the artist a consistent aural rock (bass note) and hard spot (chord) to lean their natural pitches into. In AmerAfroEuroLatin musics, we need both to bring the magics |

A history nutshell. Our very oldest chordal instrument could very well be the harp. And it was probably open tuned right? It goes all the way back to where our written record begins, so with even just a couple of strings, when plucked together, voilà ... a chord :) So all the way back we've had a 'chord potential', and now today ... ? R.O. ! |

|

All of the 'modern' Americana harmonies we enjoy today come about thanks to, what was still into the 1600's, a rather complex mathematics that creates our equal temper tuning. Based on the division of the octave interval in 12 exactly equal parts, it is this and only this 'equality of the pitches', that allows us to stack pitches one atop another to sound any variety of chords that are all in tune, singly and together. Any chord, in any key center, sounds in tune with any chord in any other key center. So, anything from anywhere? Yep, that's the idea. It is the math of equal temper tuning, applied to tweak the natural organization of pitches from nature, that energizes our full spectrum array of modern harmony. |

Euro based harmony. Of our 'modern' Americana harmonies, most if not all of the wide variety of amazing chords we can create today, are sourced from our European ancestors' side of our Americana family music tree. These Euro cats, through centuries of trial and error and even more in some cases, invented, perfected and then imported for us, the whole tamale of the functional harmony. |

So thanks to the luthiers, who can build this magical mathematical precision of equal temper tuning into our various guitars, many which that play like absolute total butter through their entire range of pitches; so three plus octaves, there are no real bounds to creating chords on our guitars. And for piano? Well, pianos and keyboard instruments in general, are designed for chords. Pianos do a lot more too of course, but specialize in harmony. From the triadic groups of pitches for backing folk and rock songs all on through the 7th's and 9th's of blues, pop and funk, and on to the 11th and 13th's of bossa and jazz, all of these chord colors and in any combinations of their pitches, are equally available from each of our 12 unique pitches of the chromatic scale. |

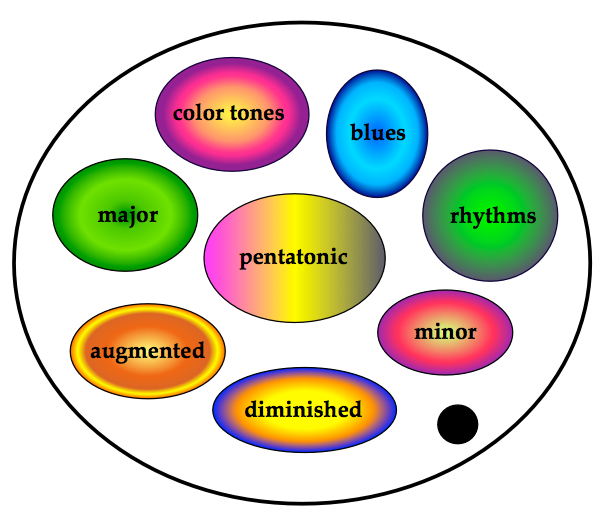

It's a lot of resource once we're hip to the 'che che changes.' Our main theory topics here include; the spelling of chords, chord voicings, chord type, chord cycles, rhythm guitar, color tones and the evolution of chords through our musical style. And as best we can, maintain our core philosophy that pairs numbers of different pitches used to create a chord, with the musical style we'd most commonly find it. R.O. ! One more nut. |

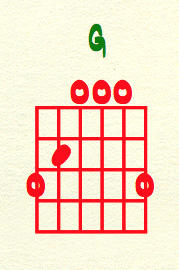

A music style nutshell. In learning about our Americana harmony, that the number of different pitches in any chord will help determine where we are in our spectrum of styles; folk ~ blues ~ country ~ rock ~ pop ~ bossa ~ jazz For example, while there's six pitches in an open 'G' chord voiced thus, yet there's only three different notes or pitches in the voicing. There's three 'G's, two 'D's and one 'B.' Here's the shape; six notes three different letter name pitches. 'G B D.'

Know this chord shape ... learn it here if need be. |

AmerAfro based harmony. Now we add a fourth note to our three note 'G' chord to make 'G 7.' Recognize this 'G7' chord shape ?

Our four different letter name pitches are 'G B D F.' Now we bring the blues hue, just swap in a blue 7th above the root, just like this. So from a '3 different note (triad) chord to 4 different note 7th chord', we've added the blues, one of Americana's tap roots. Our styles morphs from folk styling to blues and blues roots grow into all of the other styles; blues and jazz from earliest times, surely 50's rock and roll is G7 / V7 based, and into the fusion of the 60's and 70's, blues rock, jazz rock, Southern rock, pop rock, soft rock, hard rock, into the often cubism mix of hip hop. Flip it over. We can trend to reduce the number of pitches in chords towards five, to four, or three or two or octaves / one, while judiciously choosing from our color tones to set the mood. A full spectrum of colors :) |

|

Motion to Four - bring the 'gospel' to Americana. Motion to Four is the basis of 'bringing' the gospel quality to our musics. In any style, motion of One to Four and back, and forth ... will bring that sense of spiritual freedom that our gospel musics embody. While there's no limit to the variations for a song, and its spirit will surely take it where it needs to go, chances are that along the way one of the destinations in near every song in the Americana song book will include 'motion to Four.' Crazy as it sounds, when there's no Four chord in a song, it takes on this different, fusiony sort of vibe, as we need this 'motion to Four' to bring Americana's gospel to the story being told. So in our studies of harmony, we want to parallel; a bit between style and how this motion to Four is achieved. Are there passing chords between them ? Is there a V7 chord involved ? Just a straight off rockin' move ? Maybe a Two / Five cadence or a descending stepwise motion in the bass line from One down to Four. Or ascending, walking stepwise up to Four. Hip to the idea of 'motion to Four?' So for us theorists, we can think along the lines of musical styles, and see if there aren't a few common, tried and true ways songs in a particular style, that composers have solved this essential harmonic motion in our AmerAfroEuroLatin musics. And just as interesting is how songs, once they get to Four, find their way back to One and home. For some great songs start on Four, or its close diatonic relative, Two. So probably just food for thought here, but theory food that might feed the puzzle bulldog, finding missing pieces of the compositional puzzles we call songs :) |

Scale / arpeggio / chord. Once we've some pitches to work with, and begin to organize them into our musics, they most often take the form of a scale, mode or loop of pitches. The ability to diatonically morph any scale into its arpeggio, and from arpeggio into chords is for many, enough theory to solve a career's worth of musical riddles as they come along, thus well worth the price of admission to this show. |

Spelling chords. One essential theory skill is developing the rote ability to spell chords, and any chord really regardless of where we find it in the music. This is an absolute game changer in a couple of ways. Our improvs can more readily evolve from working over changes to creating lines through the changes. Sounding out the pitches of a chord through spelling in itself becomes a melodic, improv idea, giving rise to permutation and its near endless possibilities. |

Spelling chords is an easy way into the analysis of any written music really, thus a key to unlocking a vast resource of new ideas. In my own case, it was this ability that opened the doors to the vast J.S. Bach library of musical magic that first challenged me at college. Herr Bach's collection is so chock full of melody and harmony ideas it's a bit overwhelming, so as theorists we might just kick back and enjoy it all through listening, When we hear something we dig, we use our chord spelling abilities to go through the scores and puzzle out individual pieces, then find them on our guitars and create our own magics :) |

Open tunings. Once even a basic understanding of spelling chords is cool, we can readily open tune our guitars to any number of chord possibilities. Instruments open tuned to a chord are also a slide players dream come true, especially for the three chords of blues songs. |

"Open G." Among the most important open tunings initially for creating the Americana sounds is the open G of the banjo. For its transfer to the guitar in say the 1830's or so, and that's a guess sorry, becomes an original tuning for the early blues artists. |

Some of our first recordings of the blues from the mid 1930's have songs performed in an open G tuning. Blues is an Americana root and gives us the 'rub' of pitches to create the blue hue, that we can find somewhere in near all of our styles, through the generations of players. |

Four essential triads. Triads are created in major and minor thirds, we in theory call this 'tertian' harmony. And when built on the same root pitch, we get four and only four possible combinations. Once we rote learn these we are good to go :) |

Adding the 7th. Building triads up beyond their three notes opens up some new pathways in musical style. For example, add a 'blue / b7' to any major triad and the tritone bearing V7 chord evolve. Once here, the idea of chord type emerges also, a way to categorize chords based on what quality of third and seventh they contain. Once the seventh is added to any chord really, we open up the additional color tones above in their diatonic arpeggios, all of which can be altered in some way. Thus, our harmonic universe and musical styles may expand dramatically, through this simple addition and evolution. |

The diminished triad / chords. The diminished chords are so named because they make a plain old minor triad just sound more minor by ...

There's just the one diatonic diminished triad and two types of diminished 7th chords. The 'half diminished' 7th is diatonic, built on Seven. The fully diminished 7th chord is diatonic from the harmonic minor scale. We also find this fully diminished seventh color in the V7b9 chord, which becomes a super clear portal for chord substitution of the jazz languages. We've a symmetrical diminished scale also, for creating these triads and fully diminished 7th chords. |

The augmented chords. Augmented triads are so named because they are constructed with a major third and ...

... augmenting meaning to raise by half step. Its diatonic source, like the diminished seventh chord, is the harmonic minor scale. Also, we find this triad / chord in the pure symmetrically whole step constructed patterned whole tone scale. a whole tone = a whole step = one fret :) |

The 'sus' chords. The 'sus' chords contain one or more pitches that have been 'suspended away', through pitch and rhythm, from where they would 'normally' in musics. Most common is the 'sus 4.' In this chord the third of the triad is moved up to the fourth, where it creates a feeling of suspension, in that the triad is no longer truly major or minor.

In the realm of classical music and its theories, every possibility, both harmonic and melodic in regards to chord tone / non- chord tone, has a label. In our Americana studies here, a simple numerical representation, as the 4-3 mentioned above, is enough of an indication for astute artists of a suspended note or chord. |

The diatonic three and three. "There's really only a couple of places it'll go." This a quip from a pal that describes the chord progressions in the music they dig. Surely just a bit of theory slang, the 'diatonic three and three' describes that; in each of our 12 key centers, we can diatonically generate the One, Four and Five chords for both relative major and minor tonalities. |

That we weave these six chords into the harmonic progressions for most of our Americana songs, is the bit of theory to rote know in the most common key centers we each play in. For in knowing this bit of the theory, our diatonic improvs take an easier first step in moving from soloing over the changes to soloing through the changes. With arpeggios? Yep, one sure way to outline the chords in a song. |

'Three chords and the truth.' Originally, these five words represented a formula for what constitutes a well crafted song in country music. That just three chords, and a story of with truth, is what is needed for a story told in a song. It is included here for us composers who might ever think that simplicity in our own work just might not be feeding the bulldog :) |

Chord progressions. We use this term to talk about the sequences of chords that support our melodies that create our songs. The best and most essential chord progressions are in ...

'... listen to this song ... ... find the root notes of the chords, ... determine major or minor of the chords ...'

Like this. G C G C D A- D A- C D ... G ... :) 1 4 1 4 5 2 5 2 4 5 ... 1 ... Key of 'G' major ? Yep. We use both of these to name out chord progressions. A '1 4 5' is a 'G C D'er' in the key of 'G' major.

Most chords move by fourth or half step, in more jazzier sounding styles. Then there's composers such as 'Steely Dan.' If there are no songs with the progressions you want, you'll have to write your own. Which you will figure out how to do :) Got a bass line story ? |

Harmonic cadences. In definition; a progression of two or more chords that bring music to a close, stopping / resting point, new section etc. This can be in both musical sounds and time. Euro classical artists tend to theory define these way more than we Americano's but either way, the results are the same. These cadences are categorized by what degree of 'closure' or 'finality' they bring to the musical phrase we find them. Some are 'stop signs' sort of pausing in the music. Others are the end of the road finality, song is done. And then there's cadences in relation to modulation or changing keys, that look to trick us into thinking the music is going somewhere else entirely, then doesn't go to its 'expected' spot. Found in both major and minor key centers, composers will borrow cadential motions from one to jazz up the other. The songs and music styles we each love to listen too and create are going to be a solid source for ideas to initially understand chord cadences. Find a fave and listen to the end points of the phrases, figure out what the artist is doing at these points in the music. These are the cadence points. Once we know the concept, we'll shape the pausing and stopping points in our musics to suit its story line. |

Chords of musical styles. To understand the relationship between chords and musical styles, we take a fairly scientific approach and simply bend it to musical art. Knowing that we can break the rules when necessary to express our ideas, our studies here are again numeric and even a bit close minded if you will. We do this to simply learn the basics that help us to modernize our creative. Number of different pitches in any given chord begins to determine what styles we generally create with it. Three note triads for folk and country. Four pitch 7th chords for blues. Five different pitches in a chord? We're jazzing things right on up :) |

Chord voicings. Chord voicings are simply the way we stack up their pitches to make our chords. 'How are you voicing that chord? Is a common enough question. We initially look at our pitches the way we understand them from nature and then apply these principles as best we can to the guitar and piano. Thinking from the root pitch as the #1; 1 3 5 / 1 5 3 / 1 5 7 3 / 1 7 3 5 etc. |

Chord inversions. Chords by their very nature have a couple of pitches. The order in which we stack them up is their voicing. Once we have a voicing, we can juxtapose these pitches any way that best expresses the art in our hearts. These various configurations of a chord's pitches we term a chord's inversions. The different inversions of the pitches of any chord give us different options and textures of our harmony. There are three basic inversions of a triad, and we simply evolve things from there. Inversions 'lighten' a chord's texture. The 'heaviness' of root position 'lightens' up in first inversion. Inversions create nice passing chords in progressions between the principle chords of a song. They help us adjust a chord's 'weight', when we've a bass player, keyboards etc., in the mix. That our chord inversion labeling system follows a numerical evolution, makes it easier to understand and rote learn. We've a 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th inversions. And like most of our theory, once the principle concept is in place, we can apply the exact same theory to any chord, in any key center, in any style, and in any song in any of our local universes. |

Chord color tones. This term might be a bit old fashioned now but what it represents is still the same regardless of the labeling. A chord's color tones are simply the notes we add to our three note triads. And while any notes are possible additions to a triad, there's a systematic approach that organizes the remaining nine pitches ... 3 triad notes + 9 colors tones = 12 ... creating an evolution of sorts. For as the chords evolve as we add on color tones, we'll see a corresponding evolution of our musical styles. |

Chord melody. Most probably a slang term in academia, the idea of a 'chord melody' is simply a way to arrange the pitches of a melody to be supported by chords as we perform the song. And while each of us as artists will find our own ways to arrange and present a song's melody and chords together, there's a few tried and true ways to begin the process. Click over to the chord melody page to explore. |

Chord type. In theory, the idea that any chord can be a specific 'type' of chord, is simply a way to categorize chords, thus simplify our learning process of harmony. While mostly a jazz thing, which often deals with lots and lots of variously related chords, chord type is a basis for building cadential motions and chord substitution. |

In UYM, there are just three types of different chords. Based on the quality of a chord's triad and added 7th, rote learning these basics empowers us to apply its theories to really any chord that comes along. In doing so we streamline our learning process; we no longer have have 12 different root named chords of the same type but one category that they all fit into where they all function in a similar manner. In jazz theory, thinking 'chord type' opens the portal to the realm of chord substitution. We'll exchange one chord for another of the same aural qualities that share a few of the same pitches, that functions the same way in a song. This all leads to understanding the historical evolution of our Americana system of harmony. |

Chord substitution. As the term implies, we're just replacing one chord with another. We mostly do this for variety and to streamline our musics for faster and faster tempos. Of course as we do this, our musical style might evolve also. Yet, faster tempos can often generate more challenge and excitement, both of our own intellectual process and for listeners and dancers. Initially, chord substitution theories are quite simple, knowing the basics can dramatically expand our palettes for both performing and composing. |

Evolution of Americana harmony. While really a vast topic to sort out, in theory, we've a relatively easy task. For we can simply follow our own historical timeline and let our ears decide this evolution. |

For by using the core diatonic basis of thinking 'inside / outside', the theories of our harmonic evolutions are a gradual evolutionary process towards chromaticism, and the degradation of our sense of a tonal center, tonal gravity and its corresponding sense of aural predictability. |

Also, we Americanos can compare our evolutions here to our Euro brethren. In doing so have the benefit of compare and hindsight, two essential perspectives that can sure up our own works and artistic directions, while being a modern day creative music theory empowered musical artist :) |

Diatonic chords, One / Four / Five in major and minor. An often overlooked aspect of the basic six diatonic triads, the ones used to create the chord progressions for the vast majority of our songs, is that in theory, they are already pre-programmed into being the One / Four and Five chords. The same One / Four / Five chord progression? Yep. The 'three chords and the truth' chords? Yep. The three chords of basic blues songs? Yep. The 'G, C, D'er' of folk and country? Yep, absolutely. |

One set of '1 4 5' triads is major and one is minor and they all come from the same group of pitches. Let's extract these chord pitches as three note triads in the relative key pairing of G major / and E natural minor. Example 2a. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

One / G major |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / C major |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

Five / D major |

. |

. |

D |

F# |

A |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

One / E minor |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / A minor |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

Five / B minor |

. |

. |

B |

D |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

Ever seen the letter named pitches presented in this manner? This is just a fairly common way to spell out the pitches of the diatonic chords. Here created from the perspective of the 'G' major and 'E; minor key centers, we measure and numerically label each of the pitches from 'G', then 'E', which assumes the position of One. |

This adding of the numbers to represent letters is nothing short of potentially super game changing for the emerging theorist. Using numbers instead of letters allows us to project any theory ideas or principles equally from any of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale, advancing our understanding of the entire system. |

Cool isn't it? Two sets of One / Four / Five chords, one major, one minor. The ultimate sets of threes for the AmerAfroEuro harmony mix and match. No end to the chord progressions they might create in all of our styles. Super rote learn these chords for maximum success. Example 2b. |

|

Wow, in this graphic we get a variety of theory coolness. Diatonic relative pitches and keys, the upper (major) and lower (minor) case Roman numeral chord degree symbols, standard notation of the pitches, string tab note locators and line grids for chord shapes. |

Do consider working in some fingerpicking to help locate your single line melodies from within these open chords. Sing, hum or buzz along with your melody to get it just how you want it to sound, feel and flow. Make it all dance with the magics of time :) |

So did you already have these chord shapes under your fingers? Cool. No, then just learn them here if need be. In learning new chord shapes; try to slowly strum each chord a time or two then move to the new shape. Simply back and forth till the new shape is mastered. The strumming is usually the easy part, making the finger change between chord shapes the challenge. |

|

OK with the last barre chord B minor? As it is the same core shape as A minor just up two frets, the index finger becoming the barre replacing the nut of the open strings. Evolving open chords to the movable barre chords is often a dramatic step for the evolving guitarist. |

Bass lines of harmony. Bass lines often begin by just playing the root pitches of each chord in succession, of the chord progression of our song. This becomes a story line for this song. Typically, bass lines develop along a couple of tried and true ways. We can use the diatonic pitches of our key center as passing tones between the roots of the chords, creating a 'walking bass line.' These lines drive along on the 'big 4' groove to bring the swing. We can arpeggiate each of the chords and 'rock around the clock a la boogie woogie and stride too' around, cycle of 5th's the roots a bit, locate the diatonic 3 and 3, add seven maybe and lay the basis for all of the colors. |

|

Review. This index page for topics for harmony and chords has a few of the keystones for building up your harmonic vocabulary. From spelling out chords to diatonic chord progressions, to color tones and musical styles, to chord type and chord substitution, there's topics to explore. These all knit together in theory, now U've got to knit the components you need into your own understanding, so as to have the pieces needed to play the songs, to tell the tales you want to share. |

Advanced theorist. Once an artist hear clear major or minor in triads, and can spell out the letter names of the chords through all 12 key centers, the rest is fairly easy. Hearing root motion of chord progressions and understanding chord type, opens up into the vast universe of chord substitution. From this point, it's about what we can hear, understand and utilize in our own creative endeavors and collaborations. The tritone interval is a catalyst to most points beyond. Understanding Coltrane's evolution through the harmonic resource and a bit beyond to the '#15' colortone portal, are additional pathways to wander and explore. |

"It's amazing how much you can learn if your intentions are truly earnest." |

wiki ~ Chuck Berry |

References. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

Find a mentor / e-book / academia Alaska. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music and can help you with your studies in the musical arts. |

|

Always keep in mind that all along life's journey there will be folks to help us and also folks we can help ... for we are not in this endeavor alone :) The now ancient natural truth is that we each are responsible for our own education. Positive answer this always 'to live by' question; 'who is responsible for your education ... ? |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

~ |