|

~ Arpeggios / Chords ~ ~ arpeggio pitches stacked into chords ~

~ naming chords and a quick history of harmony ~ ~ diatonic melody notes and chords ~ ~ the '1 4 5' major triad notes ~ ~ adding on a 7th to diatonic triads ~ ~ chords without a 3rd and 7th ~ ~ chord shapes are riff generators ~

|

A definition of an arpeggio ... The playing of a chord with its notes sounded in succession, rather than sounded simultaneously as in a chord ... |

A definition of a chord. A chord is simply three or more notes played / sounded simultaneously. With three notes we name them triads. More than three notes? Chords. |

In a nutshell. Simply to complete the diatonic discovery process of how a scale's pitches are reconfigured into its arpeggio, and now, how this arpeggio is segmented to create its chords. Associated topics include; naming a chord, the four types of triads, their inversions, spelling triads, adding their 7th, and diatonic harmony and chord type. In exploring these topics we also gain a new way to listen, interpret and understand the harmony that surrounds us in music. And is there a 'theory' way to 'numerical identify' of chords as the music moves along in time within a key center ? Yep, sure is. |

Advanced theorist. For the advanced theorist reading here, if you're cool with the theory of how chords are constructed and can quickly spell the letter names of really any chord that might come along, click ahead to advance your knowledge forward by exploring new components such as; chord color tones, the three unique chord types, common ways to create chord voicings, their inversions and chord progressions. The last link out, chord substitution, opens a pathway into the colossal universe that we can examine by timeline to a better understanding of the evolution of Americana harmony. |

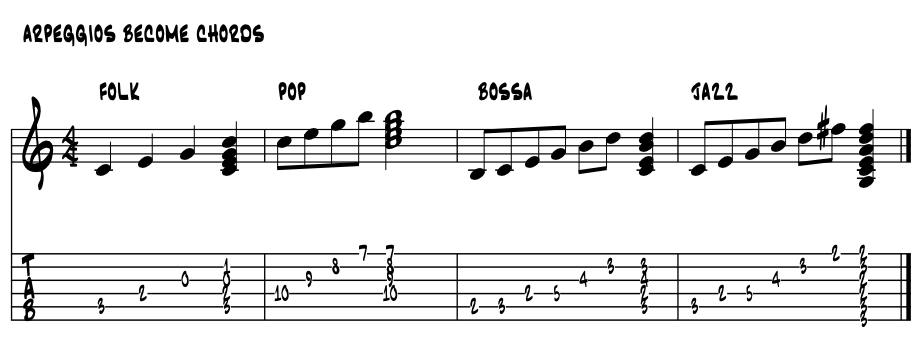

Harmonizing melodies. When we come up with a nice melody, or are learning a new song and trying to figure out where the chords go as the words move along, we theorists want to 'harmonize the melody', meaning we want to have chords to support the notes of the melody. Guitarists love to do this as their instrument provides the big three; melody notes, full chords and rhythms to motor things along. So with some gumption, 'working up tunes' for solo guitar performance is a solid option. |

Composers. A lot of what we might write is usually influenced by wanting to get the musical stories we write played, performed, recorded, shared. What is popular in each our own 'era' of creating music models possible forms to emulate while learning our craft. Melody on top, supported by a chord, which is supported by a bass note, is a start point that we've used now for a couple of hundred years. melody ~ 'C' chord ~ 'C E G Bb' bass note ~ 'C' For beginning artists and composers, here's a three step mini-curriculum for getting the basics. As in the above example, and in all of the studies that follow, our central tonic key center pitch is 'C.' It can all go pretty quickly for energized composers, arrangers and songwriters. |

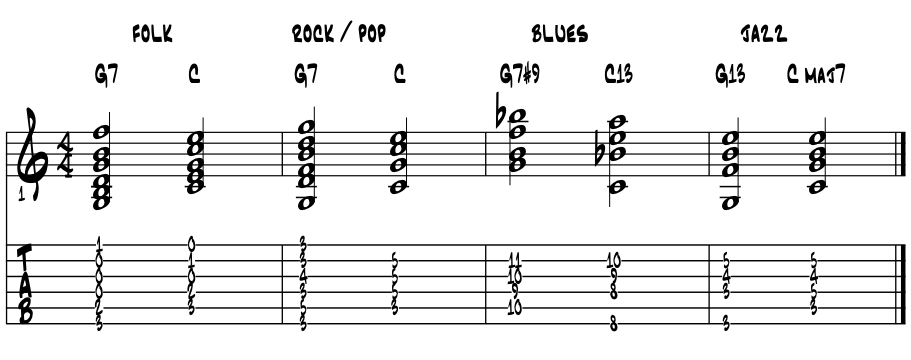

And for guitarists. Harmonizing melodies are puzzles for mixing the aural colors for telling the emotional side a song's story. Again the basics of it are pretty easy to do, almost in a mechanical numerical way. So a lot depends on style and how much to to 'jazz it up', moving our 'chord melody arrangement' along our style horizon. |

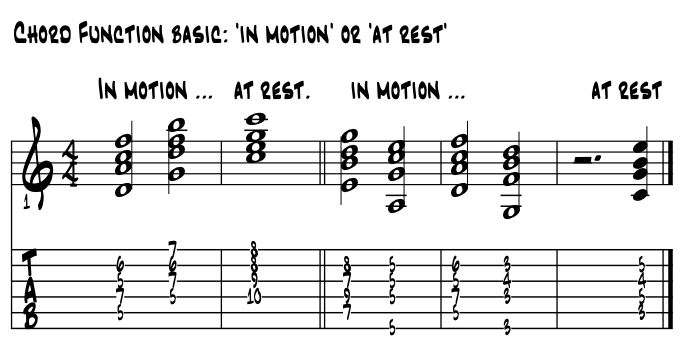

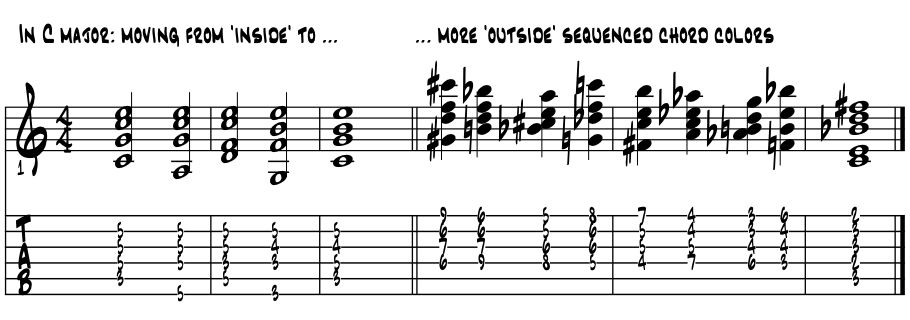

Tonal Gravity. How complex we want to 'arrange' the harmonies for a song knows no real bounds. In this range of complexity, the style of music we're writing for often creates our chord choices for supporting a melody note. A spectrum of styles pans across a spectrum of complexity. The idea of a 'tonal gravity' is simply about creating a pull of one chord towards another as a melody moves along. Near the midpoint of this style spectrum is where we draw the 'diatonic line.' From which side of this line we build our harmonies gives us a way to begin to find our chords to harmonize our melodies. Lean one way and our tonal gravity shows clear where the harmony is going, as say with a 'G, C, D'er' song. Lean the other and the pull of the gravity is diminished, helping the music float a bit making the bar lines begin to go away. Musical form plays a role too in harmonizing melodies, as say in a '12 bar' blues. For if the song we want to harmonize is a blues song, the basic three chords fall right into place. That we can 'jazz it up', and how to jazz up a 12 bar blues is what we want to study. And in these studies we learn the principles of harmonizing melodies. |

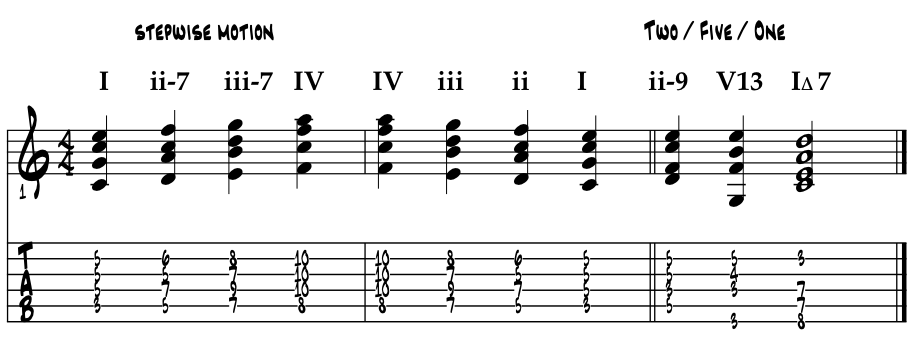

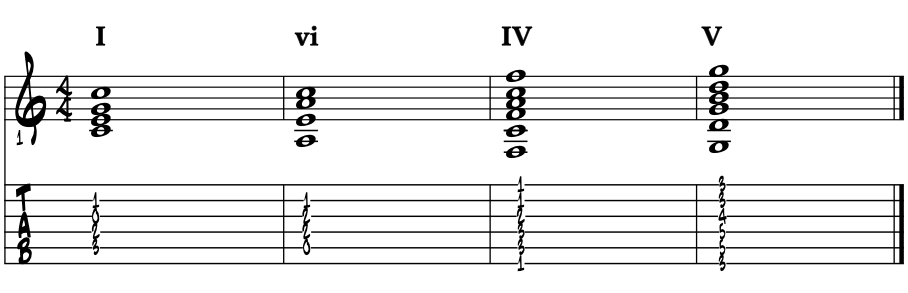

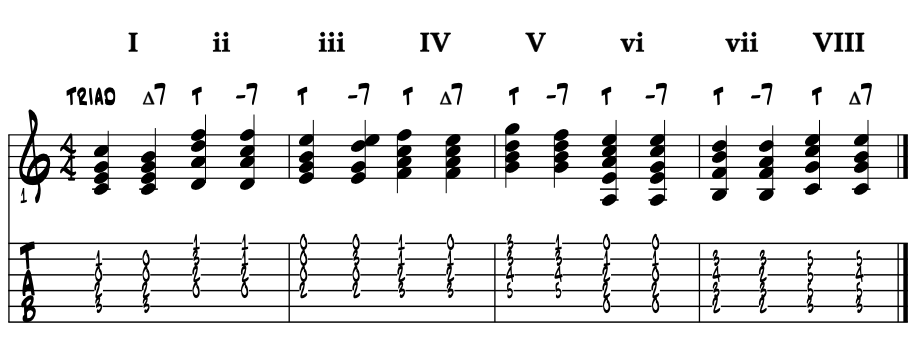

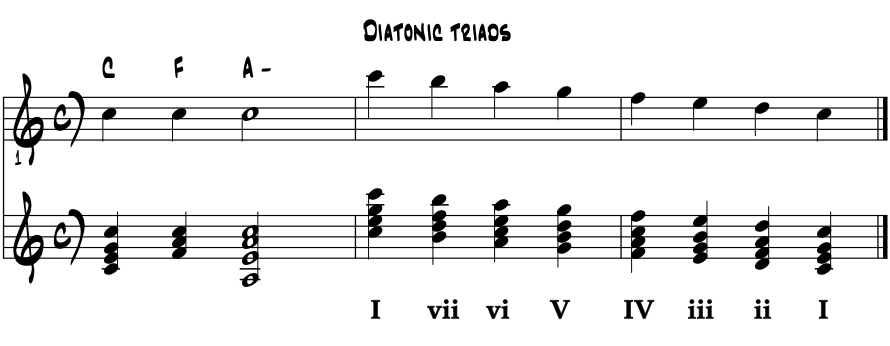

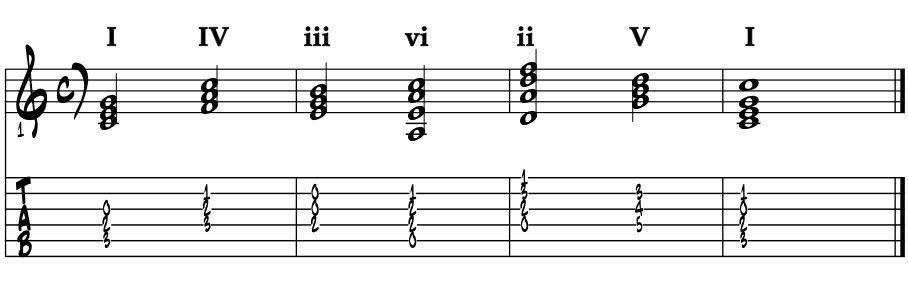

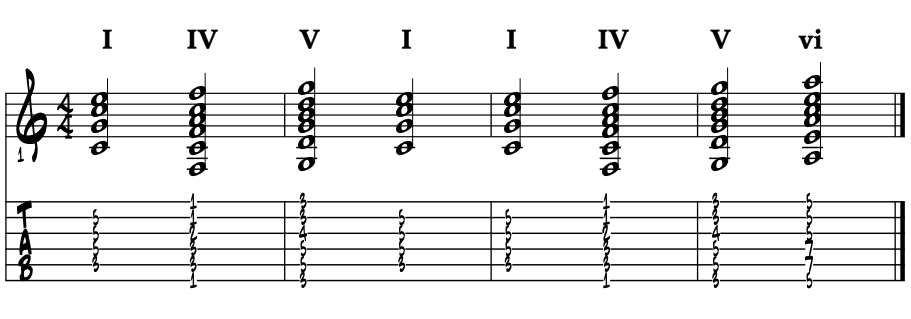

Diatonic melody notes and their chords. In diatonic style harmonization of the pitches of the major scale, any of its seven melody notes can be supported by any of its diatonic triad / chords where we find the pitch. Please examine the following chart. Thinking 'C' major. Ex. 1. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

major scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V7 |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEG |

DFA |

EGB |

FAC |

GBD |

ACE |

BDF |

CEG |

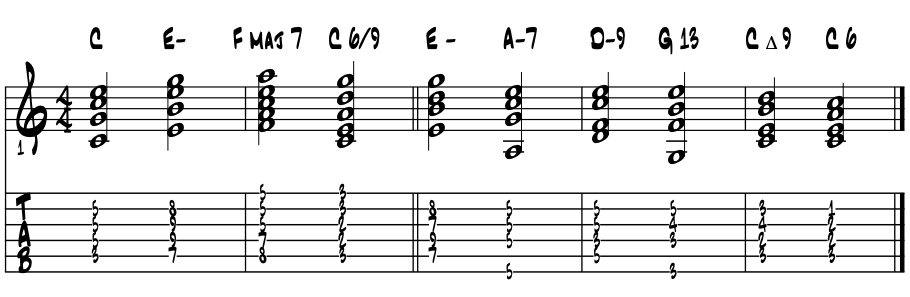

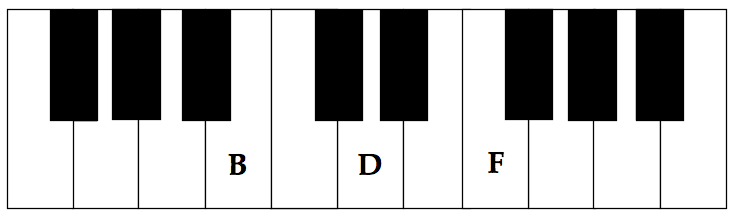

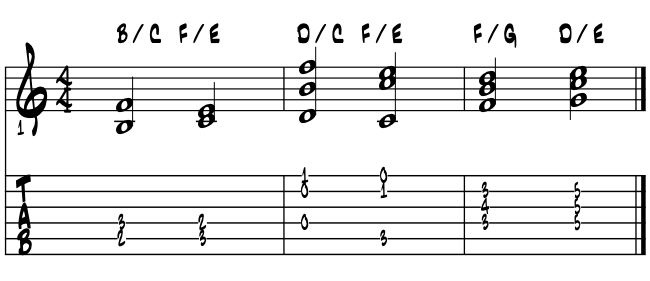

Using bold type, our melody note 'C' is found in three of a key center's diatonic triads. So in looking to support this melody note, these three triads become some first choice possibilities. Here's the chart's letter names in standard notation. Example 1a. |

|

So a song in the key of 'C', any of of its diatonic pitches can find supportive chords in the same way from the same chart spelling out its triads. And of course, each of the seven notes gets its own triad for support :) And for a different key? Just rewrite the chart with the appropriate letter names of any of the 12 relative key centers. |

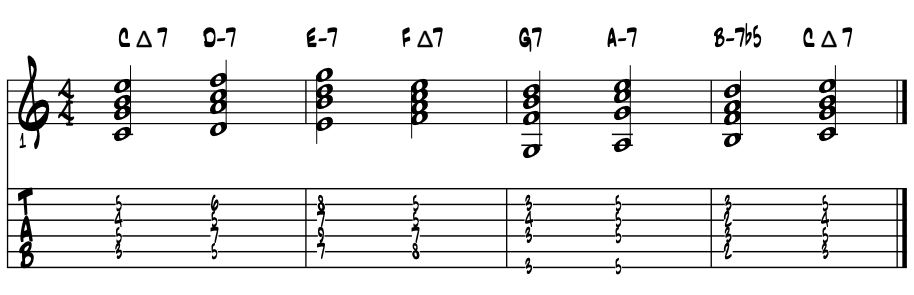

Jazz it up. An easy way to jazz up the chords to support a melody is to add the 7th above each diatonic triad. Examine the following chart. Example 1a. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

color tones |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Cool? So by expanding beyond the triad, and remaining diatonic, we gain another possible chord to support our 'C' melody note. From this point we've expanded options to; add additional color tones, think by chord type for finding supportive harmonies, add in some blue's hue', and consider crossing over the 'diatonic line' and begin to find chords that are beyond the chosen key center. |

Quick review. The basics of harmonizing melody centers on the style of music, and to what degree the song is within its chosen key center and its degree of diatonic center. A key skill in doing this is to be able to spell out triads and chords, first within a key center and then in terms of its chord type and chord function. These go hand in hand and become the basis of exploring beyond the diatonic. Again, the style of the music that we're presenting the melody in initially determines its harmony, and then we can jazz it up from there :) |

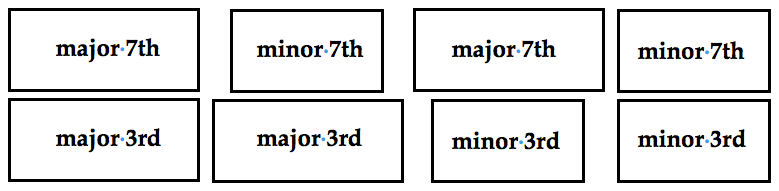

About our chords; tertian harmony. New term for you? Cool, another Essential's first. The term 'tertian' generally implies a cycle in three's. We music theorists use the term 'tertian' to describe the overall structure of our harmony or chords. It simply means that our chords are constructed with our two types of thirds intervals; major and minor. We can stack these thirds up to the stars and it's all still all tertian at heart. By far and away, tertian harmony, or chords built in thirds, covers what we hear chord wise in all of our Americana styles of music. Even the 5th's of metal? Yep, to a certain degree. Everything. Other chord building possibilities? Surely. |

Based on triads. The vast majority of our chords, in any style and coloring, are based on the three notes that create triads. Triads consist of a root, 3rd and 5th. While the 3rd and 5th have variables, our root pitch does not. Only the one root? Yep. As we'll explore in the following discussions, the variety available with just three pitches is rather remarkable. As a solid basis for really any and all chords, triads surely carry the big weight of harmony in our musics. |

Why spelling chords is important. So what do we gain by knowing the theory of diatonically spelling out the letter names / pitches of chords within key centers? Mostly the ability to unlock any chord's pitches quickly and find the good ones for making melodies. And locate the clunker notes too :) With any chord, we can then examine each pitch and uncover its relationship to the all of the pitches within a song. |

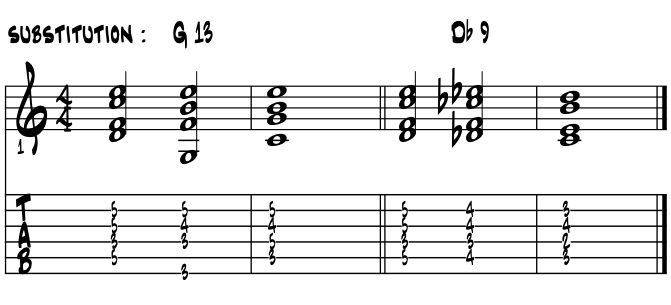

Once the diatonic spelling of chords within a key center is well in hand, a next evolution is to know chords by type. Built on the triads, we add a 7th to determine a chord's type. Like the primary colors of red, yellow and blue, we get three different chord types. Once in place, any chord from anywhere can be nestled into one of thee three chord types. While mostly a jazz idea, chord type is a great way to catalogue chords and find ways to substitute one chord for another, creating variety if desired and a 'discovery process' when looking for a missing piece for one of our puzzles. |

And gain as players? We create an essential tool of learning that strengthens our ability to discover, by our own labors. Spelling chords helps to solve musical puzzles, helps us build our own chord shapes from just theoretical letter name pitches, create chord melodies from lead sheets, find common tone pitches and motions between chords and generate pitches, arpeggios and chords for creating our improvisations, oh and understanding and using color tones ... to name a few. |

Learn the theory by numbers. In the learning method of Essentials, much of the process is about swapping out numbers to represent the letter name pitches associated with our musics. And it just may be that this numerical representation process is the best way to understanding, and more so to catalogue, our vast array of harmony. |

While pitch letter names are essential to sort things out and keep track of what's diatonic within a key center, any way to shorthand the material to be rote learned is a blessing. So in the following discussions we'll again use numerics and synch right up to our core Essentials philosophy; how the number of pitches involved can influence and even determine musical style. |

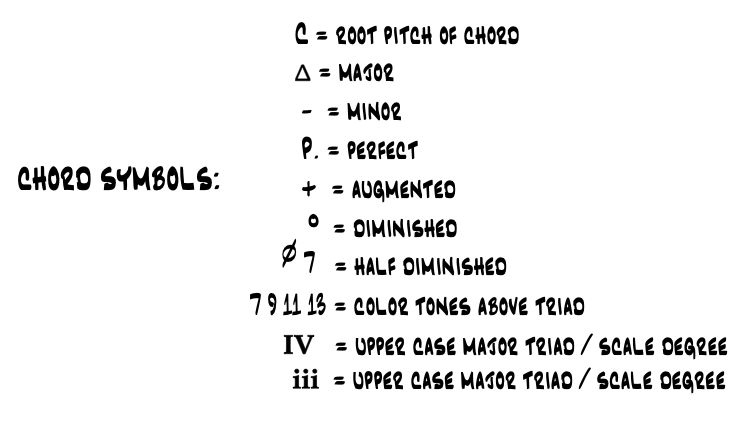

Chords ~ naming triads / chords. In naming any triad or chord, the basis is Yin / Yang; is it major or minor. This is determined by the third of the triad; root, third and fifth. Beyond the triad there's the numerical colortones which we simply identify by number also. These numerical colortones are further defined by their interval relationship as measured from their diatonic root pitch. That we always think from the root pitch is the mantra we mere mortals should adhere to. Here's the basics in chart form. Example A. |

|

Natural theory just sounds good to us :) As with our perfect intervals, named for their aural purity, we can follow the natural harmonic series' pitch sequence in creating our guitar chords, we simply follow nature's way to sound good. Mirroring the harmonic series' initial wider intervals for the bass and lower pitches, the higher pitched color tones are closer together. With our lower to higher pitched strings, all of this science of pitch is of course built right into our modern six stringers. |

Re-sciencing nature's own pitches. Here we delve for a moment a bit deeper into nature's acoustical source for our pitches and their organization. We started this discussion way back in our 'silent architecture' and continue here to sure up our basic science, as we move into our discussions of harmony and all things chords. |

In this next example we view the ascending harmonic series from the root pitch C. The initial two intervals, the octave then perfect fifth, follow the interval sequence that Pythagoras is said to have used back 2500 years or so ago in creating the initial basis for our music theory; octave, perfect fifth. Example 1b. |

|

|

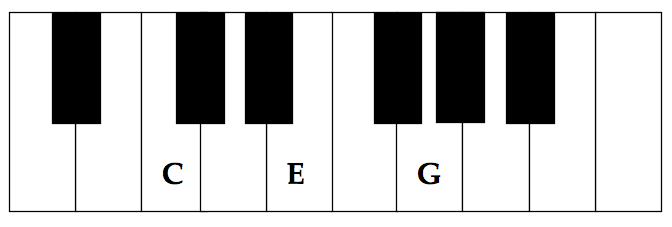

For theorists, once we pass the initial octave, fifth, octave, so the 'C ~ C ~ G ~ C' sequence, we see our pitch letter names emerge from the overtone series. Big and bold, 'C ~ E ~ G' turns out to be a stack of intervals that creates nice sounding voicing for guitar. Imagine that! Built right in from the Mother :) And those three pitches over the first barline? The C, E and G? The are a key to our music universe, for they make a major triad. |

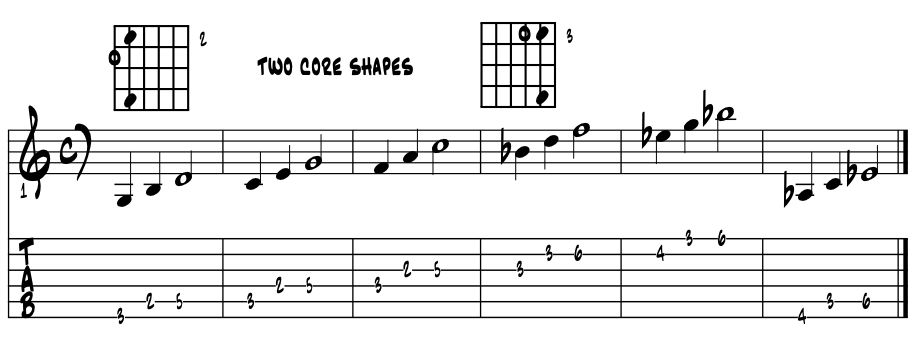

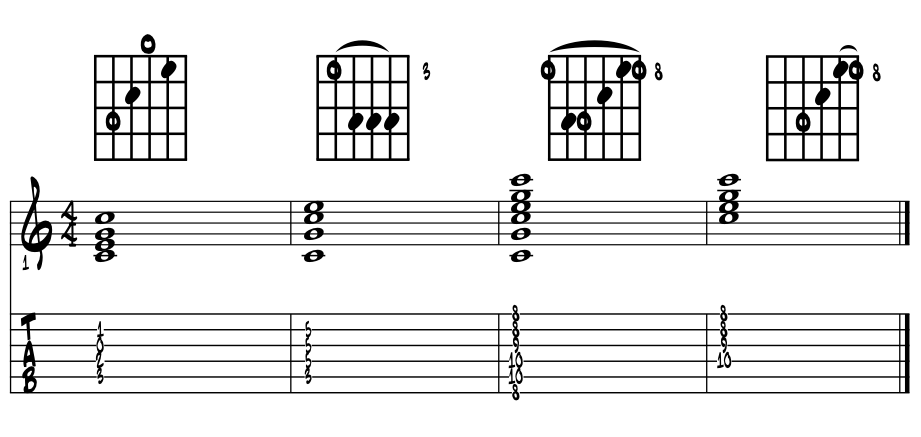

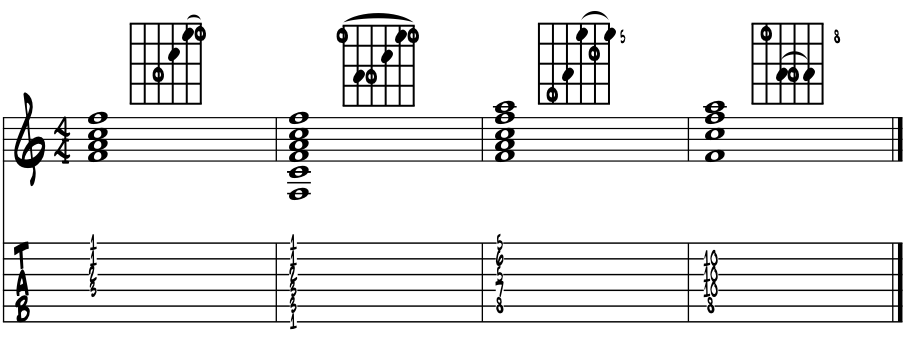

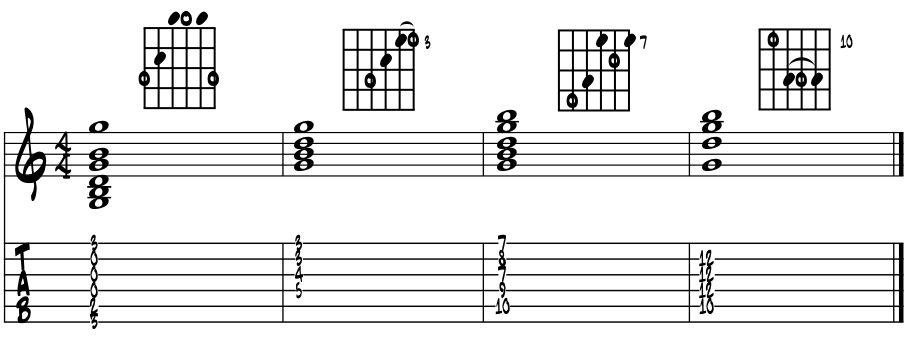

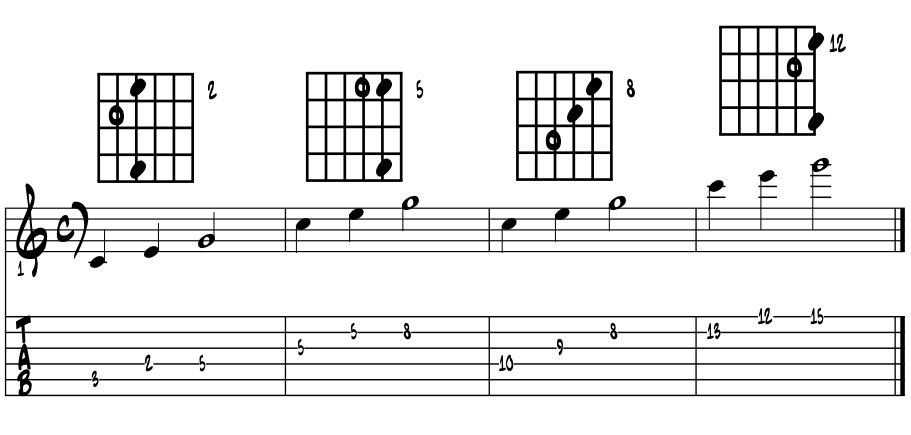

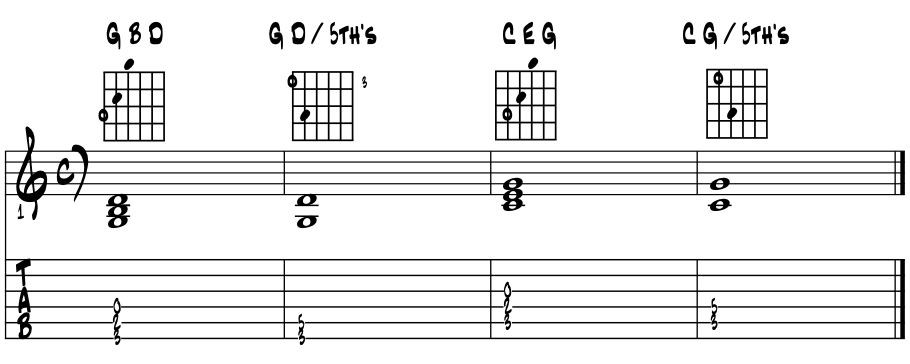

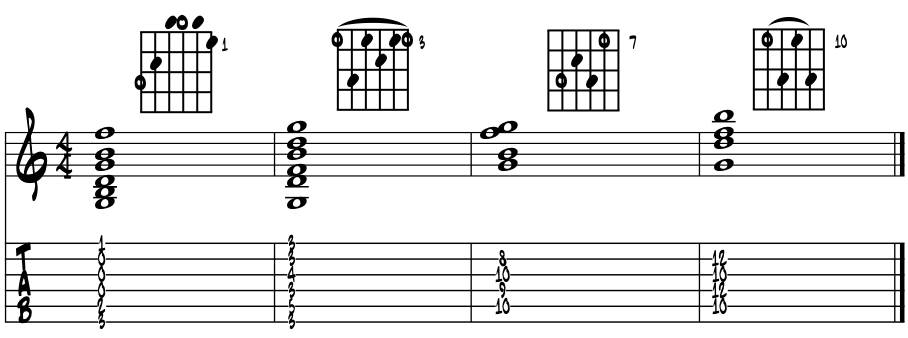

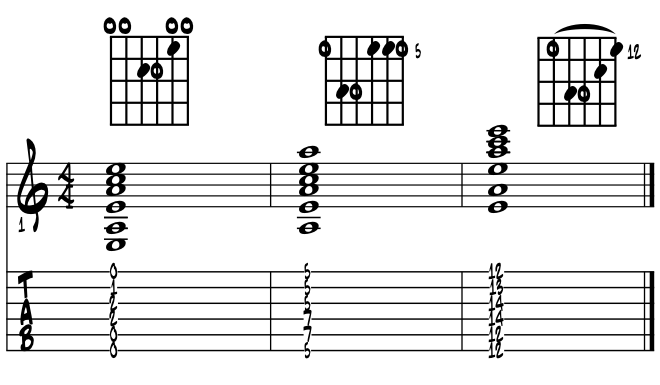

A very cool and popular chord, the major triad has formed the basis of much of our music for the last couple of millennia. So a couple of thousand years? Yea. Same triad? Yea. The tuning of these pitches has evolved, but the structure is the same. For guitarists, initially there's really just two or three core triad shapes on the instrument. Thinking 'C' major. Example 2. |

|

Familiar? All movable shapes? Totally. Cool. Learn them here if needed n'est-ce pas? So if popularity of intervals is in part determined on their inclusion in melodies, then the major triad ranks right up there with the best of 'em. In improvisation and its historical evolutions, in both approaches of 'over' or 'through' the changes, the major triads have played a vital role in telling the tales, for they quickly bring an exciting and joyous sound to the music. That triads also determine the major / minor aspect of our idea, thus form the emotional basis of our stories throughout all of our musics. |

As modern guitarists. As guitarists we enjoy the full spectrum of possibilities provided the homophonic style of stacking pitches into chords to support melodies. Our equal temper tuned axes provide the tuned pitches to create any chord we might imagine. And we can stack different voicings together, as when there's two guitars in the band. |

Author's note. Lately I've been working with a smokin' blues lead player who proudly says he does not know the names of chords, and even adds that they could care less about a chord's name. OK, no worries, we end up working out parts so as to not play the same voicings, positions etc., the neat thing is how by knowing the names of chords, I easily create a 'stack' of two different chord shapes, searching for that 'wall of sound' style for recording from the 60's. I then usually play their chord shapes when I comp for their soloing. |

|

Quick review. So thanks to our history record keepers, we have an amazingly varied body of guitar art to study created by the hard work, determination and creativity of the cats that have come before us. That all of our pitches, scales, arpeggios and chords, as well as the rhythm motor to drive it all forward, are all potentially right under our fingers on a standard, six string guitar instrument that travels well, is really nothing short of simply amazing. Even awesome? Yea, might qualify. |

So just what are triads / chords? Our triads / chords are select groups of pitches all sounded all together. In our resource evolution, we evolve a scale group of pitches into its arpeggio, then select distinct segments of three or more pitches of the arpeggio, then stack these pitches atop one another and sound them all together. Bingo, chords. What could be simpler? |

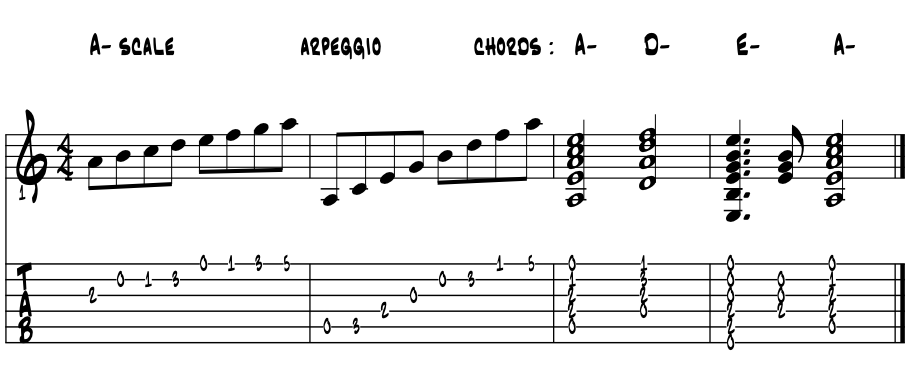

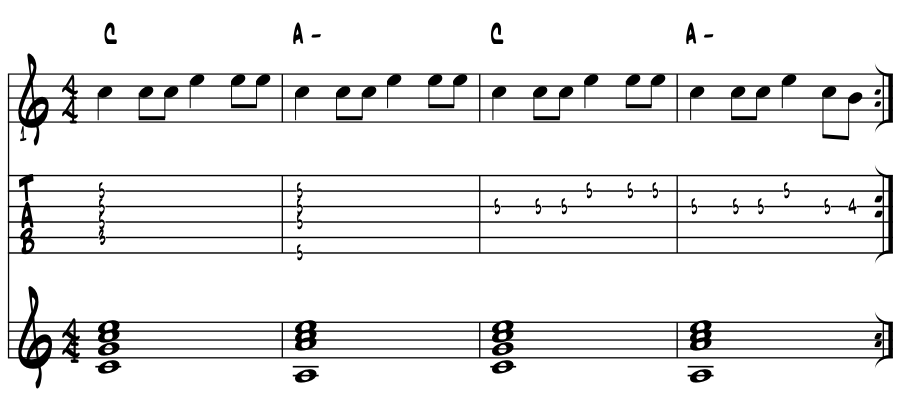

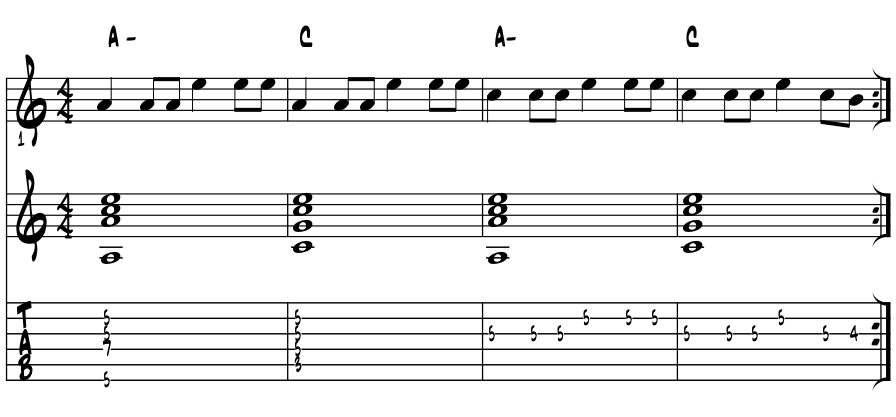

Is there more? No not really. Scales, their arpeggios and chords are our three main aural components for making songs. Of course we do have to motor them along in time. So on guitar we get to be the motor too ! Here is this basic evolution of our resources using the pitches and key center of A natural minor. Example 3. |

|

Same pitches create three components. Sensing how this is going to work? Scale becomes arpeggio becomes chords. Once Ya got this pitch conversion process solid, you'll have it forever. And, you'll be able to teach it to those in need while always being hip to the changes :) |

Same pitches for C major and A minor. The following discussions will also begin to weave ideas from both our diatonic C major and A minor together. For as we look at the evolution of chords, we'll come across many well worn chordal pathways of our Americana music, that are based on mixing the major and minor chords associated with one key center. |

These same paths become our well worn chord progressions, simply the traditional ways we've woven a balance between this two stranded, musical DNA double helix of major and minor, all while using the exact same group of pitches. |

An evolution. This major / minor mixing process starts diatonically then gradually evolves. We evolve by simply adding select pitches from our remaining five to get the sounds, chords and cadential motions we want. That surely 7 + 5 = 12 yes ? |

Evolving a scale into its arpeggio and chords. Since this whole tamale can be such a simple process, we just might as well scare it up from scratch the first time through. We can start by extracting the seven pitches of 'C' major from the twelve pitches of the chromatic scale to create the key center of 'C' major. Example 3a. |

| chromatic scale | C | Db | D | Eb | E | F | Gb | G | Ab | A | Bb | B | C |

| C major scale | C | . | D | . | E | F | . | G | . | A | . | B | C |

|

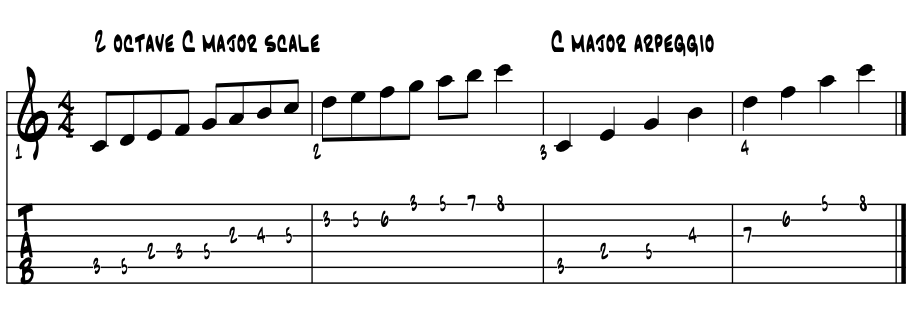

Next, we need a full, two octave 'C' major scale loop so as to be able to completely reconfigure the pitches into its complete arpeggio. We apply a bit of magic here; that by simply skipping every other pitch in the two octave group, we create its entire arpeggio. Example 3b. |

1st octave |

2nd octave |

2 octave C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

C major arpeggio |

C |

. |

E |

. |

G |

. |

B |

. |

D |

. |

F |

. |

A |

. |

C |

|

Cool with this? Kinda super crucial total rote learn this 'double octave' metamorphosis of the pitches, scale into arpeggio, scale into arpeggio ... and learn that poem :) |

Reveal the magic. That in 'skipping every other pitch', to evolve from scale to arpeggio, we're 'leaping' by 3rd's, both major then minor. That scale groupings are constructed stepwise with major and minor 2nd's, and arpeggios, like chords, are constructed by leaps of major and minor thirds, is set in stone music theory of today. |

So easy enough yes? That in creating chords, we now simply stack up the arpeggiated pitches of bars 3 and 4 respectively and sound them simultaneously to create chords or harmony. Example 3c. |

|

Clear as mud right? And that is all there really is to the evolution of our arpeggios into their chords. Sorry it took so long to get here :) So we can create chords in this manner from any arpeggio and create arpeggios in the above manner from any scale? Yep, pretty much. |

Of course, the vast majority of the Americana chordal sounds, in all styles combined, come from the major / relative minor groups of pitches. And by adding in the blue notes to the mix, our complete core Americana palette of colors evolves. |

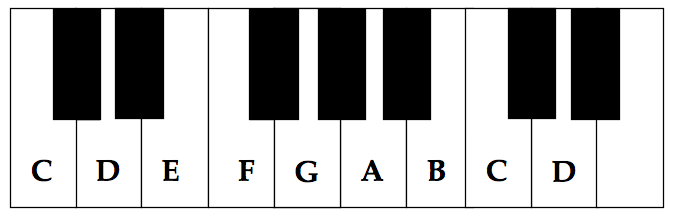

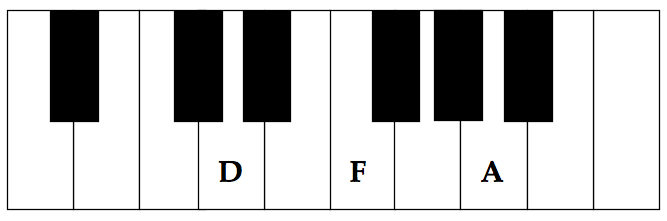

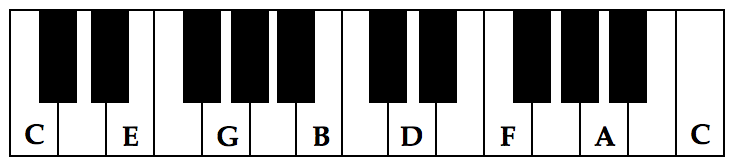

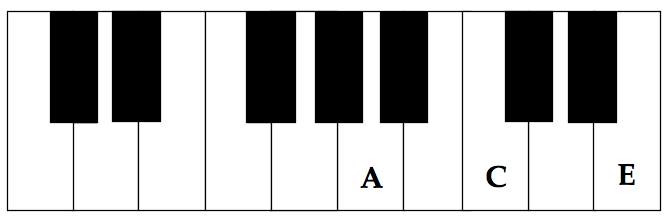

At the piano. Projecting this scale / arpeggio / chord theory onto the piano, we can see how all of our pitches of 'C' major live right on the white keys of our standard piano keyboard. Please examine the pitches of the 'C' major scale on the piano keyboard. Example 3d. |

|

So, built right in? Yep, ain't that a beauty. The diatonic pitches of 'C' major, its arpeggio and chords are sounded by the white keys of the piano. Its relative minor key of 'A' minor too? You bet, just the white keys. Now examine the diatonic arpeggio and chord pitches of 'C' major. Example 3e. |

|

All clear? In the above graphic, it really jumps out how we've consistently skipped every other note of our scale group in creating its arpeggio, thus chords. Cool? Also from this graphic, see how clearly any of the pitches of the arpeggio can become the root of the chord, its triad pitches the next two pitches to its right i.e., C E G ~ E G B ~ G B D ~ D F A ~ F A C etc.? These are the diatonic triads of 'C' major and 'A' minor. |

Creating diatonic harmony ~ new vistas. Depending on what theory understanding you're bringing to the table today, another valence of thinking leads us to apply these harmony building principles to our other groups of pitches. And while the major / relative minor group is really by far and away the most common for creating chords all throughout our American literature, we surely can apply this chord making process to our other melodic groupings. |

Thus; the major scale and its modes, the natural, harmonic and melodic groups and their modes, the symmetrical augmented, diminished and #15 groupings, and of course any new configuration of tone rows imagined by the modern guitarist. And while we'll surely enter this new vista to locate various gems that aren't diatonically available from our major scale, there's a whole 'nother world available to explore for those so inclined too. Is this the #15 and beyond system? Yes it is, the symmetrical #15 creates its own unique hybrid looping of the pitches and morphing of key centers. |

Back to where we started. So at the top of this page we talked about the homophonic style of composition whereby one melody line is supported by chords. As our chordal ability is pretty vast, we modernists get lots of cool, artistic considerations and techniques concerning chords; chord progressions, chord inversions, different voicings, chord melodies, picking and finger techniques to sound them, rhythmic aspects of comping, all sorts of colortone combinations, chord type, chord substitution, musical style considerations, open tunings and related chords and colors, so lots to consider depending on to what degree we include chords in the art we create. |

Chord theory. With this basic understanding of how we morph our 'C' major scale into its arpeggio and into its chord, let's go back and build our chords up from scratch, examining their organic (diatonic) basis. The following discussion surveys what's initially available. We should try to keep in mind the style of music we're wanting to create. For in essence, each musical style has its own chords that brings forth and motors its magic, while preserving its historical traditions. |

For while the pure theory discussions which follow attempt to encompass the whole tamale, in the everyday reality of performance, musical style and common practice often dictate what actually gets played in making music. Again the idea that empowered by the theory, we get a big picture of the resource, a way to understand how things get knit together in each style, thus evolving the artistic potential within each of us. |

~ super theory game changer / tertian harmony ~ |

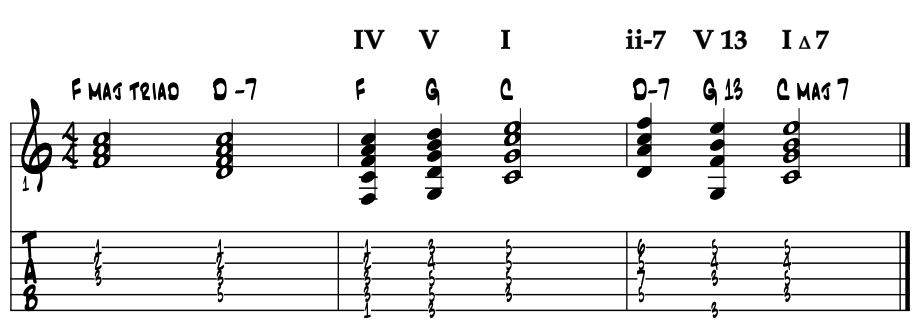

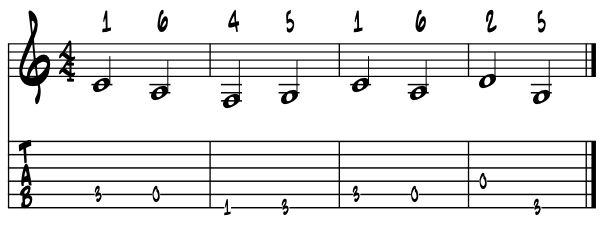

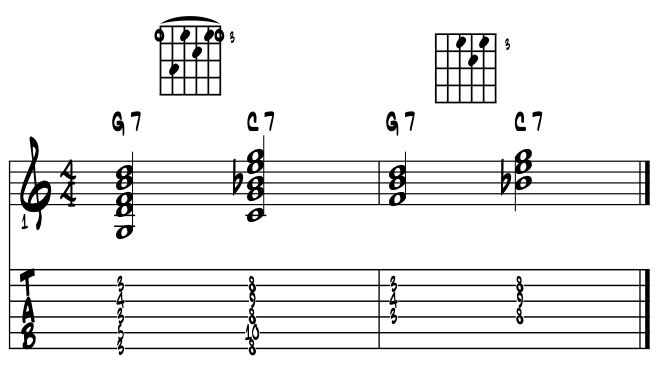

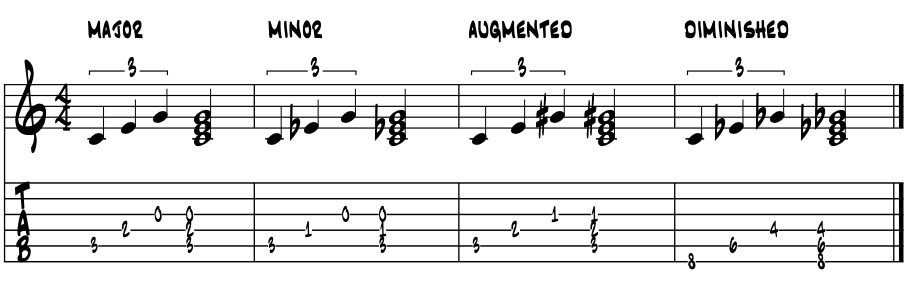

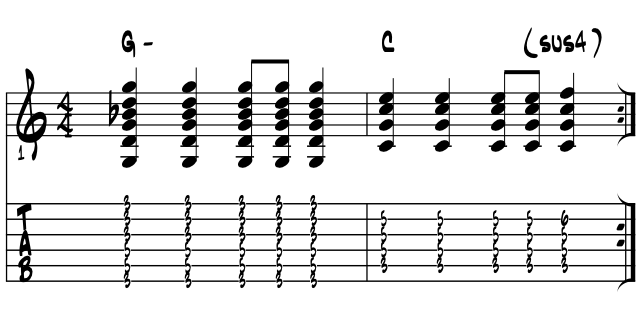

Triads / tertian harmony / 1 3 5 3 1. At the core of our musical harmony today, and in nearly all of the Amer / Euro styles of the last couple of centuries, are the three note chords built up with the intervals of thirds. Termed tertian harmony, we generally call our three note stacks of pitches triads. With just our two types of thirds; either minor and major, only four possible triads are available. Only four? Yep only four. So on the rote learn list? Yep. Here's a new melody built up by arpeggiating the major triads on One / Four and Five. Example 4. |

|

Need a new break tune? In hearing this ditty, do any other melodies come to mind? No surprise if they do really. Triads rule the day in lots of ways for us, and especially the major triad, as in this last song. Once under the fingers, fairly easy to transpose to different key centers. Works a break tune between sets too :) |

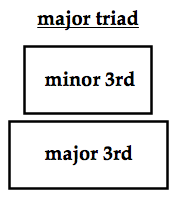

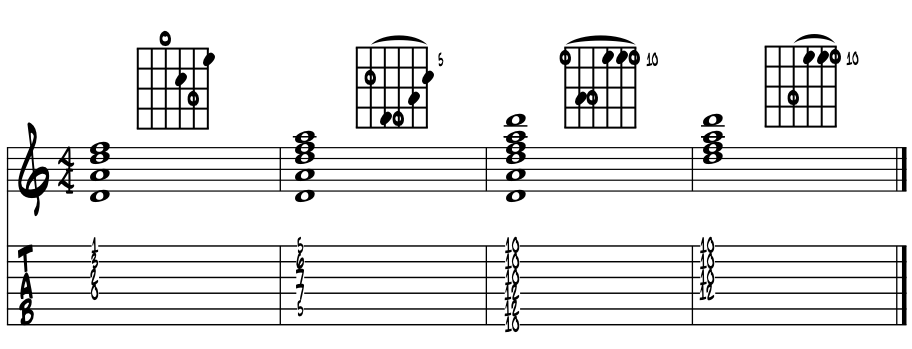

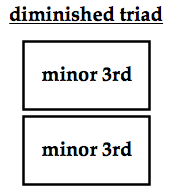

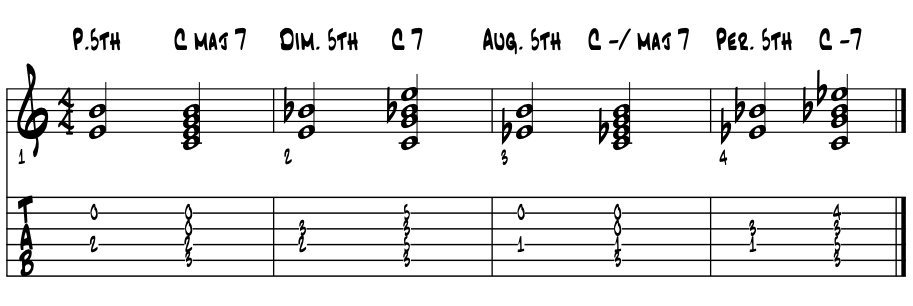

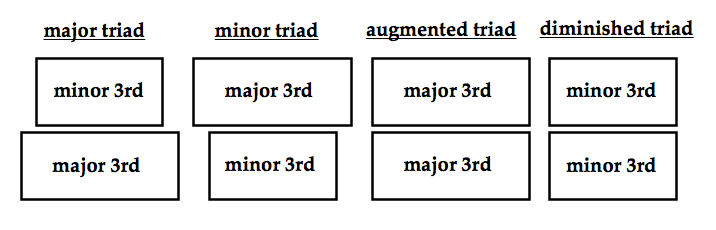

Major or minor? Triads, as the name implies, are comprised of three pitches; a root, third and fifth note. The root pitch anchors the chord, is usually the bass note, and is also the letter name we use to identify it. The third determines whether the triad is major or minor. The perfect fifth above our root completes the triad. Using two different sized rectangle building blocks to represent our thirds, do consider memorizing these four configurations. Example 4a. |

|

Four types of triads. From the above graphic, we can see the four different combinations of our major and minor thirds building blocks. These are; major, minor, augmented and diminished. The major, minor and diminished triads we get from the diatonic realm, with major and minor triads to carry the bulk of the work in our American and European Western musics. In using building blocks to create the augmented and diminished triads, the idea of our symmetrically built colors emerge. Please examine in writing and sound our four unique triads. Example 4b. |

|

Where in the music. We'll find the major and minor triads in all of the AmerEuro music we love. In all of our core folk genres, where the melodies are sung, the harmony is most often diatonic major and minor triads. The 'diatonic 3 and 3' ? Yep. The old diatonic 3 and 3 :) They've all been around for a while now and usually hang out with the '3 chords and the truth' cats. |

This symmetrical augmented color is quite a bit more reclusive yet adventurous, as its sound can be a challenge as it's not diatonic to our major / relative minor scale. The augmented triad also has three parent scales sources; the whole tone scale and the harmonic and melodic minor groups, so it delves a bit deeper into our melodic resources and off the central path. |

That said, with three parents, the augmented colors can, once understood and validated, blend into and create solid pathways for musical art that often exceeds all and breaks new pathways for the modern guitarist. |

The diminished triad is diatonic to the relative major / minor grouping, so right at home through all of the styles. Built on Seven in major and Two in minor, it usually finds its first home nestled into our very common V7 chord, the tip top traffic cop for all of our musics really. The diminished triad, and the diminished triad bearing 7th chord is usually seeking resolution. The symmetrical diminished and harmonic minor groups also are also parent scales for this 'doubly' minor triad. |

This same V7 chord is of course the tonic function chord in most blues tunes. We can also diatonically derive both the augmented and diminished colors from the one harmonic minor group of pitches. We'll find these chords peppered into the blues and pop music. |

In the jazz music of course, all of the four possible triads are employed regularly, again with the major and minor triads getting most of the work. When we begin to add the 7th's to these triads, these four core triad colors, in sound, function and malleability evolve dramatically. Leaning stylistically towards jazz guitar by chance ? |

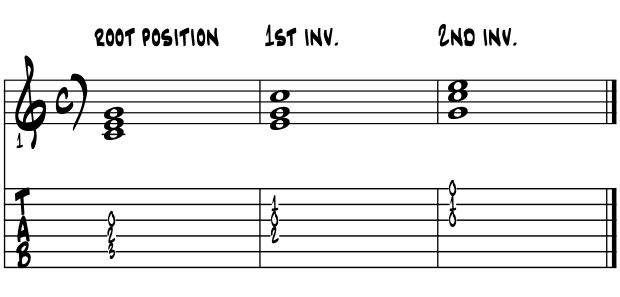

Triad / chord inversions. The three pitches of triad can be stacked any old way. Any one of the three pitches can be the lowest pitch in a stack, which is technically termed a voicing, while the chord retains its basic sound and function. |

Each of the first three possibilities we call inversions, as they simply 'invert' the stacking of the common '1 3 5' sequence of the pitches. Please examine the letter pitches and their sounds for the tonic One chord in C major as we create its inversions. Example 5. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

. |

. |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

. |

. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 (1) |

. |

. |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

. |

. |

root position triad |

C |

. |

E |

. |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1st inversion triad |

. |

. |

E |

. |

G |

. |

. |

C |

. |

. |

2nd inversion triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

G |

. |

. |

C |

. |

E |

|

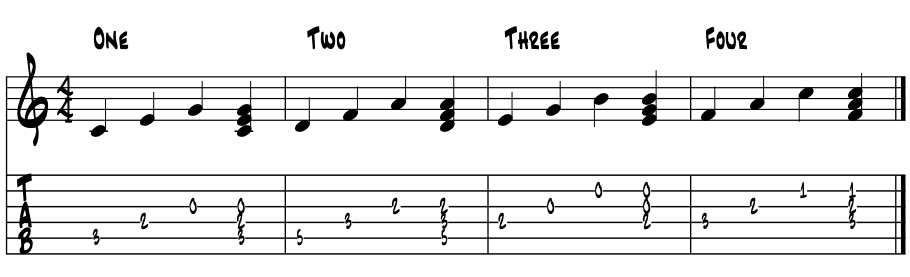

Hear how the texture of the chord 'lightens up' as we move through the three inversions? Composers and improvisors use chord inversions for variety, to smooth out root motions in chord progressions, i.e., create passing chords, also to create different degrees of forward motion in their music. This ends up affecting the flow of the music in regards to the story being told. |

So what's the difference in the music? In a word or two, tonal gravity and aural predictability, i.e., creating and playing with the sense of 'direction to' a destination, and its resolution or coming to a resting point, in the music. Inversions will also play a role in creating our cadential motions. We find these cadences most often at the end of a four or eight bar phrase, they help point to and shape the direction of what's to comes next. |

|

Root motion chords. Root position chords have the strongest, predictable and solid sense of directional motion. Their motion between one another creates the bass line / storyline of the song. Here in 'C' major, just root motion working around the cycle. Example 5a. |

|

Hear the aural predictability and gravitational direction of the chords towards the close of the phrase? Hear the finality of the V to I (G to C) cadence to close the idea? We can create the strongest sense of this closure with root position triads / chords. Of course the half note rhythmic consistency firms up the direction too. |

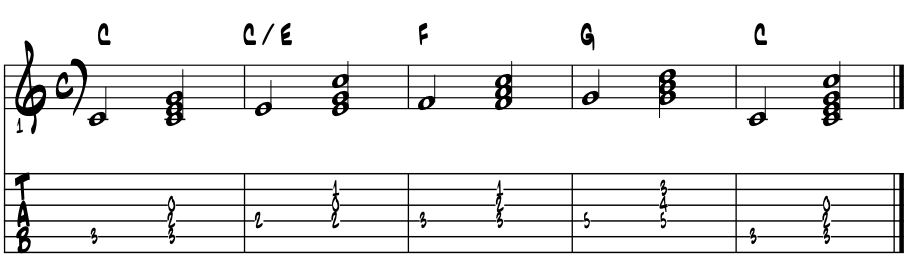

First inversion. First inversion, with the third of the triad as its lowest pitch, our chord now simply has a lighter texture, and is often used as a passing chord between One and Four. Example 5b. |

|

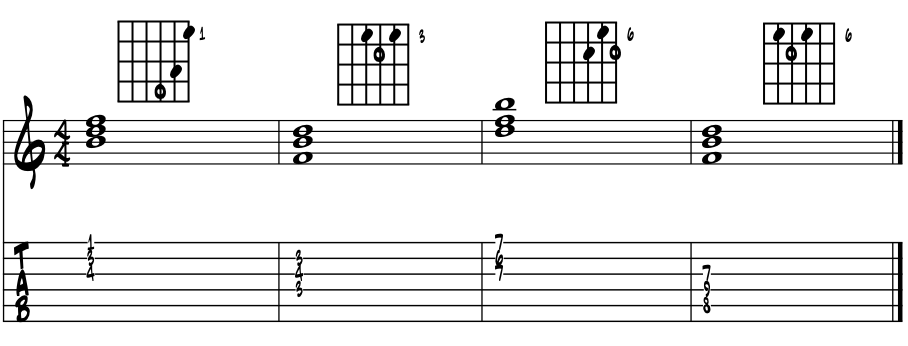

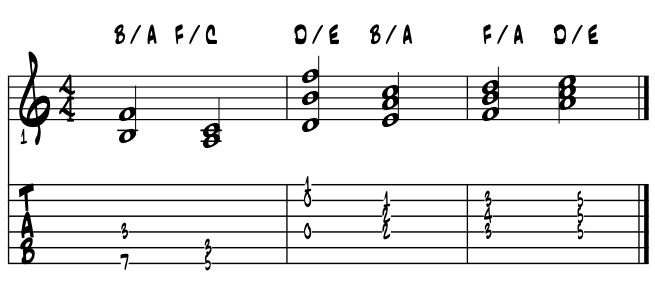

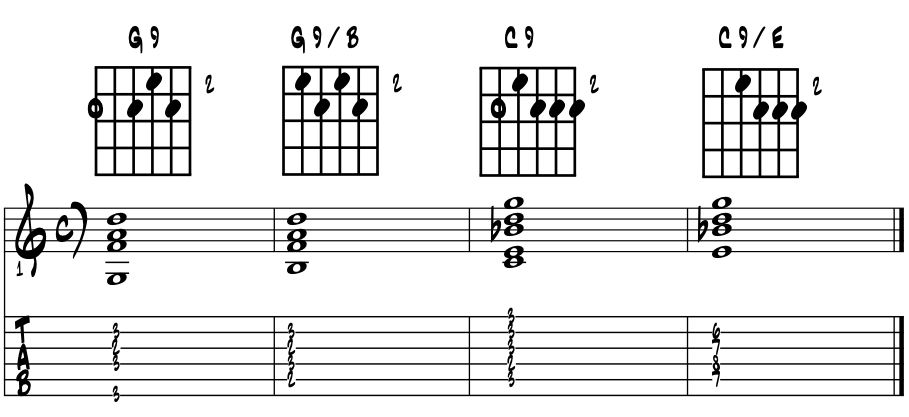

First inversion / blues gold. There's two fairly common first inversion dominant chords used in playing blues. Both are voiced to bring some added color to the chords as the 9th colortone is featured. For guitar, both shapes are fully movable up and down the fingerboard, thus movable forms. Using first inversion chords, lightening the texture, helps to give the bass player more room to find their lines. |

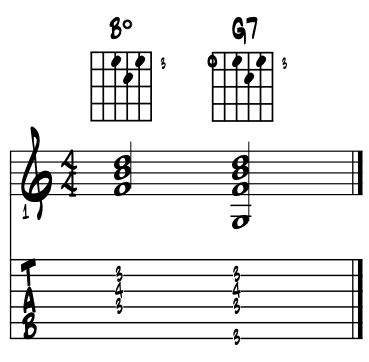

These two first inversion shapes are also structured as half diminished 7th chords, thus they each diatonically qualify as Seven in major and diatonic Two in minor. Half diminished is also the sound of the 'Tristan' chord as created by Richard Wagner in 1865. Example 5c. |

|

|

OK with the shapes and labels ? Both shapes easily handle their own simplification process too, creating additional chord shapes. Using just these two shapes creates a nice 12 bar blues chorus. |

Second inversion. Second inversion puts the fifth or dominant pitch (V) in the bass, and is also a good way to stay out of the bass players way, while thickening up the harmony. With 'C' as our root with V7. Example 5d. |

|

Easy fingering transition to second inversion ? Ah, the marvel of the construction of our modern guitars :) Bossa cats love this sort of handy root motion on their guitars, simply alternating root and 5th to create a bit of a counter line in the lower harmonic structure :) |

|

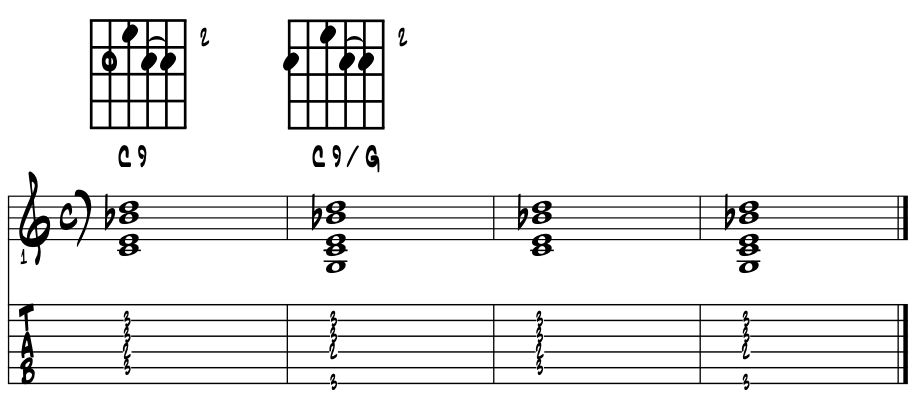

Second inversion / dominant pedal. That second inversion has the fifth of the chord in the bass, it can create the sense of the dominant pedal tone, a trick that bass players also love to use, that creates a neat sense of anticipation of something to come in the music. We chord cats might use a second inversion chord in setting up a stronger motion to Four. In doing so we achieve a chromatic motion in our bass pitches. Example 5e. |

|

Ah the motion to Four, which is probably our most common destination throughout the styles, as we move off from One to new destinations. Thus, cats like us have devised a million or so ways to get there. So we picked up a bit of a 12 / 8 feel in bar 3, on the dominant pedal. Ya hip? This 'feel' is surely a component of swing, totally setting up the 'big four' and its cousin 2 and 4. |

Third inversion. Since we're already here, might just as well add the potential of third inversion chords, so a wee bit beyond the three notes of the triad. Third inversion finds the 7th in the bass, the theory of which, in this discussion thread, we've just not quite gotten to yet. Oh well, click the link to the right to explore adding a chord's 7th if necessary. (Adding the seventh is simply including the next pitch of the arpeggio into the chord.) |

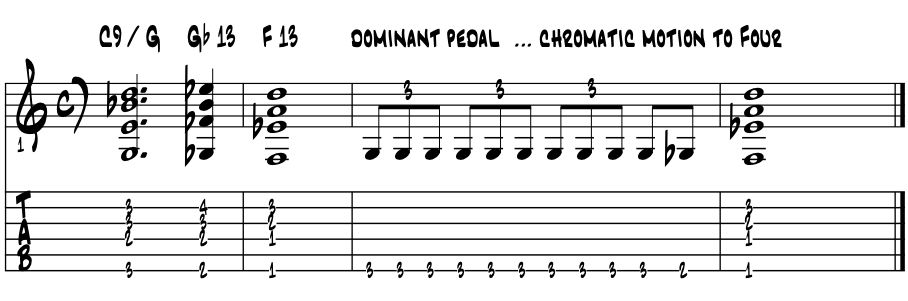

Right off there's two lovely third inversion chords that really can honk in the blues and jazz settings. And as our first inversion pushed us up to the 9th, third inversion nudges us further up in the color tones towards the 11th and the 13th. Both these next two chords are dominant chords; so a tonic chord in a blues setting and a Five chord in jazz and pop etc. As the second voicing comes from the first, let's look at how the chord evolves into being a third inversion dominant 13th chord. |

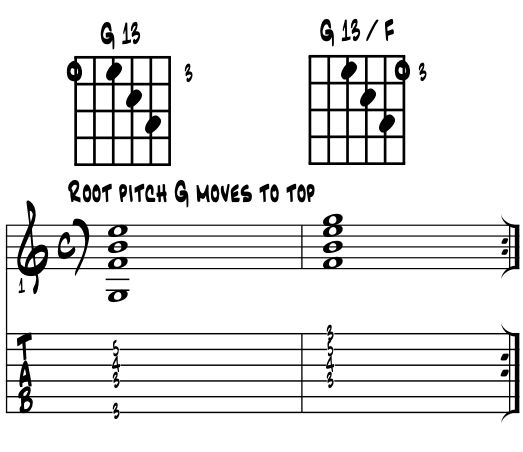

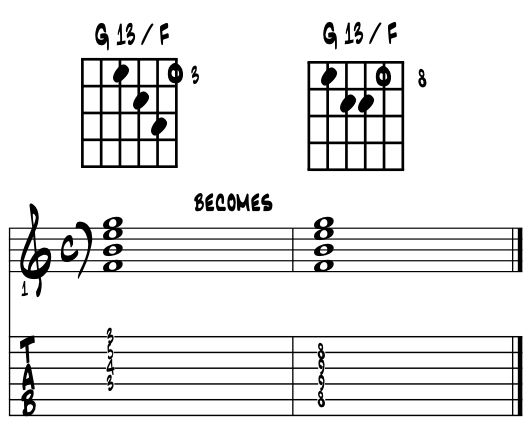

Abandon the root. One easy way to create an inversion of any chord is simply to abandon the root pitch. In this next idea that's what we'll do, although we'll move it from the lowest bass pitch to the top of the chord. Cats call this top pitch of a chord as 'being in the lead.' We guitarists do this all the time with our chord melody arrangements, especially when the pitch is part of the melody of the song. Example 5f. |

|

Same pitches on different strings. Another common trick the hipsters do is to find a chord voicing they dig on another set of strings. In this next idea, our third inversion 13th chord moves from the top four strings to the inner four to create the new magic. Example 5g. |

|

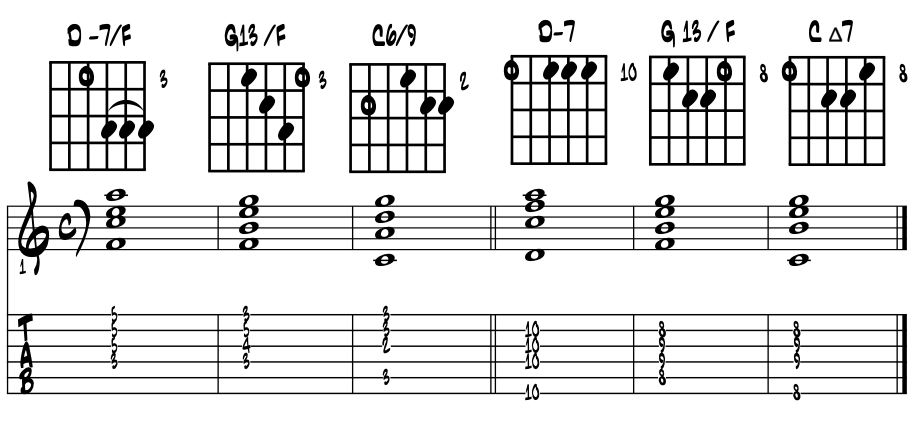

Down a string set and move the one finger and voila ... presto ... new chord. Ever done that before? No? Another first yes ! Dig these '3rd inversion dominant 13th chord shapes' in action. Example 5h. |

|

Author's note. As a jazz leaning artist, Two / Five / One is king of the progressions, we see it over and over in song to song all day long. These two solutions, and the last one especially, are my faves. Actually, I think the latter 'G 13 / F' is my favorite chord today. And for tomorrow? We'll explore and see :) Also, I think I left the major 3rd out of the 'C' 6/9 in the middle chord. Ooops my bad. Know where it is? Hint; right smack dab in the middle of the black dots. |

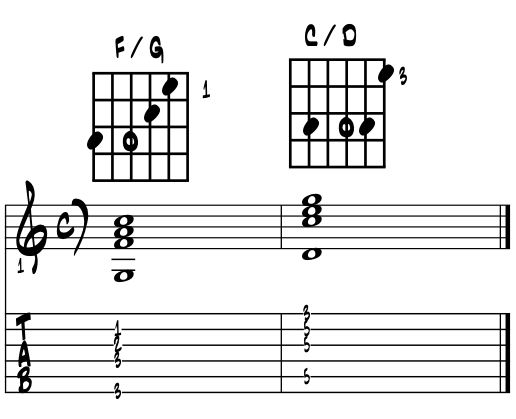

Fourth inversion. In following the sequence here, our next inversion / root pitch would be the 9th of the chord as its lowest note. There are two fairly common shapes here that cover this coolness. Both movable, can evolve these chords just like the last ones above; basically moving one voicing / shape onto a different set of strings. In practice, these two chords have found nice spots through the jazz and pop literature. Example 5i. |

|

Look familiar? As far as being a legit fourth inversion chord, in theory we're getting onto thinner ice here. For 'G is the 9th of the F arpeggio as D is the 9th of C.' But wait, don't these chords, if named from the root become 'sus' chords too? Yep. And 'sus' if more Four and Eleven yes? Tis is indeed. |

|

Luckily by knowing the theory we can sort things out in the actual music we might find them in. The first shape was used by guitarist George Benson for a jazzy cover of the pop tune "On Broadway", which went top 10 for him. It has been covered by lots of other folks too. |

|

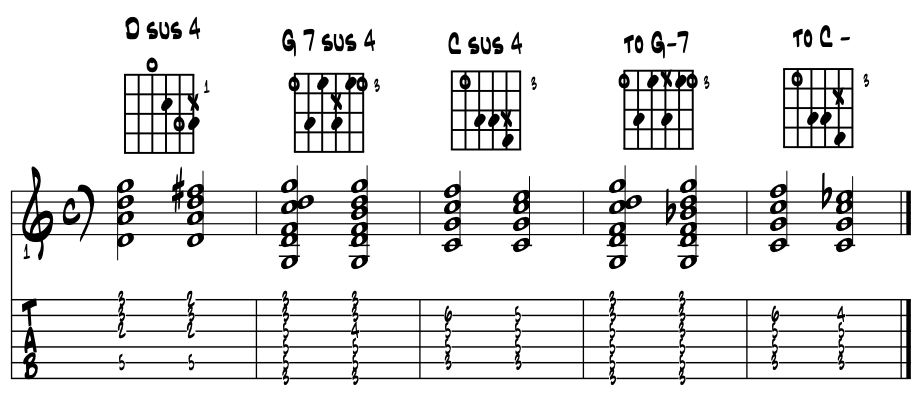

'Sus' chords. Since we opened the can here, might as well pepper in a few more 'sus' chord voicings into the mix. For there's two or three common shapes that get a lot of mileage in throughout the literature. 'Sus' is abbreviated for suspension, meaning we are simply suspending one pitch to another within a chord. We do this both momentarily, or whole sections of a song, even whole songs, with this magical, ethereal, 'between the definites' color. And just what are we suspending between the pitches? Why the centering magic of tonal gravity, giving us a way to 'pause along the way, enjoy the view,' of our stories and journeys. |

The most common suspension is to raise the 3rd of the chord to its 4th. So we're suspending the 4th which 'resolves', usually that is, down to its chord tone 3rd. Same theory for both major and minor chords. Ex. 5h. |

|

Again any look familiar? That first open 'sus' chord pops up towards the end of the arrangement of The Who's classic, and for some readers here, essential rock opera "Pinball Wizard." It is also the 'sus' chord that works wonders with other open chords. So anywhere on the folk, folk '+ anything', spectrum end of things. Add a capo into the mix and we get another ton of coolness in other key centers with the same chord shapes. While movable, this open 'D' sus shape moves up the neck, we just need to be careful to manage the open strings that live underneath. |

|

The barre six string 'G' barre form in measure 2 and 4 :), is included right up and into the jazz stylings. A bit heavy with all six strings included, it sure packs a wallop and can make the big roar, when needed to 'change' direction in a song with just one strum. That it slides right into V7 with just a one note flick makes it a true 'traffic cop lick extraordinaire.' The 'C' sus 4 of bar 3 is at heart just a big time rocker. Add bass and keys and drums and all, and depending on the room, this chord big time pumps the 'hammonator' groove and will fill the dance floor. Just sets 'that' mood of 'awe shucks here we go ... now it's time to move with the music ... let's go have some fun :)' |

Adventurous cats will pair up these two barre shapes, into a back and forth Two / Five motion. Lots of hit tunes love this minor to major, with a potential to resolve, or not as the case may be as in a vamp. Looks like this. Example 5i. |

|

Couple of big song hits ended up in copyright court with these chords too. One of which was in this key, this Two / Five / One in 'F' Major. So give them whirl and bring them to life, ya never know, maybe there's a song in them for you too. |

|

Quick review. So we started off with triads and ended up with 'sus' chords, after passing through the triad's multiple inversion capabilities. It's an amazing thing how as we sift the pitches and new combinations emerge, they often take the on form of other known components. This filtering process and the shifting of the pitches into new forms is similar to creating our art, music and beyond, as we pursue of ever elusive Muse. |

|

So what's left to discuss here are; other sized intervals to stack into chords, spelling chords, diatonic harmony within a key center, and a way to categorize chords into three unique 'types.' As each of these topics will generate ideas for links to additional discussions of art, music and finding our own muse, click away to explore then come back here for more. Perhaps to remember that a large part of learning music theory is vocabulary. We then build words and what they represent into new discussions and their resulting puzzles. |

Other chordal options? Yes of course, we have everything here, we're artists! No limits to what our curiosities might conjure up. There are theoretical variations in our chords that oftentimes, in a big way, help to determine the character of musical styles. |

The chords 'just 5th's of various precious metals. The pure fifths of all of our 'metal leaning', and thus all the various genres and subgenres of our modern blues / rock, that employ the big overdriven, crunchy sounds which generate the pure magic of near endless aural sustain of today, lean modal and function as tertian generated chords at heart. For between the root and the fifth would be the third, and from the third to the fifth is also a third. So what's the deal? Well ... historically speaking ... as the guitar amps / pedals evolved ... Sustain. As the amplifier / gear / signal / gain structure with pedals processing evolved from the 60's forward, tech engineers armed with electricity solved the sustain issues for a guitar. And with some lashups, one note can now be help out till the power runs out :) We as guitar players never had 'endless' sustain of notes and chords, since the beginning so for 500 years or so. Modern rockers / shredders / the metal leaning cats use just the perfect 5th's for their chords, ( root note and fifth / One and Five ), leaving out the third of a triad. Why ? Well, in defining where songs in these genres go, the power of root pitch sequence is enough to define where and how a song moves along in telling its story; so by style, its root and 5th. |

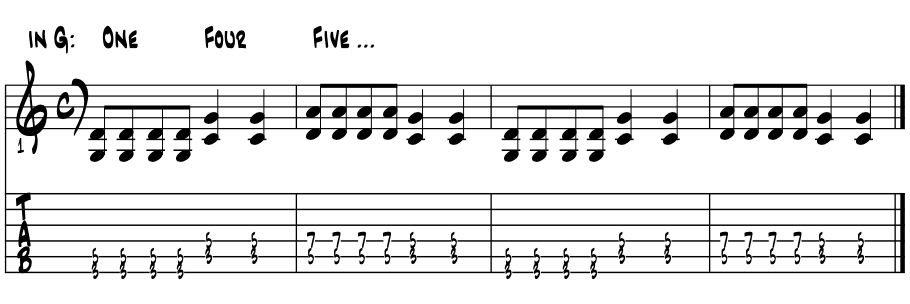

Turns out that even just three note triads are oftentimes too much pitch info for the gear to properly process. The sound is just too muddy, thus cumbersome for the clean, shred type effect desired. Sound all this out LOUD, as is often the case with various rockin' genres, and no real surprise that adjustments we're made pitchwise. The brighter (faster) tempos of the style must also play a role in this triad evolution from three to two pitches. Less pitches, sleeker, thus potentially faster. We could probably safely conclude today, in 2016, that these 5th's are the new powerchords of the last couple of decades. Here's the basic evolution from triads to fifths. Ex. 6. |

|

5th's in blues and rock. Here's a nice idea of using the fifths in a rockin' One / Four / Five motion a la oldtime classic "Louie Louie." This is the sort of lick that launched the early rockers into stardom. Cats often call this a 'G, C D'er.' Example 6a. |

|

|

Sound familiar? Learn it here if need be. And surely write a song of your own with this riff if so inclined. Take about 17 minutes. Got any hooks lying around ? |

Core of it all Americana rockin' 5th's plus. This next idea probably should be under all of our fingers, regardless of our own artistic directions. For in joys of making music in day to day jamming, once ya got it moving, it'll light a room right up. While a tough lick for beginners, it's just way too much fun not to know :) |

For through a spectrum of genres, say with traditional blues and the rockers, its pulse, or a variation of, can be felt somewhere within almost every tune. With tons of rhythm variations, a few different pitch combinations and harmonic motions, same lick on different strings sets, this lick is maybe the heartbeat of 'rockin' musics Americana', and nine times out of ten, a sure hit with the dancers. Here is the basic motion, just follow the tab numbers. Please go slow at first, for it's a finger stretch that can hurt. Using the index, middle and pinky, so the 1, 2 and 4 fingers, start slow and off you go. Example 6b. |

|

Know this motion? Slow, fast or in between, on the barest of acoustics, it get toes tappin', heads weaving and dancers itchin.' Coming originally from the 'boogie woogie' piano players of the 20's and forward, it surely has a link to a root or two of our core Americana DNA. Well worth a few minutes a day shedding to rote learn. |

|

The pure and altered 5th's, the choice of the modern metalists, are pretty much used as just the two pitches; stark, somewhat hollow and yes, quite powerful through an amplified stack. Do remember that it is thought to be the interval of the perfect 5th, sounded on the long horns, that heralded the approach of august dignitaries from the olden days. |

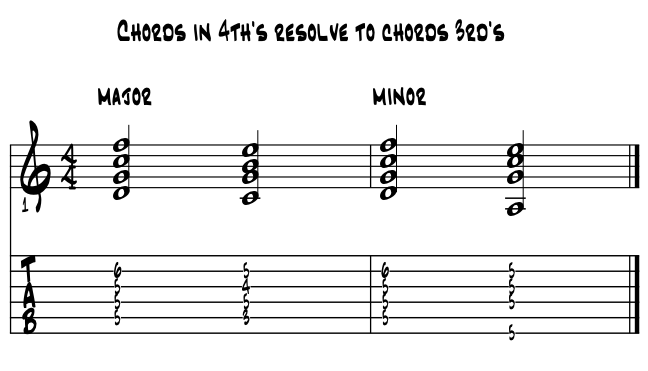

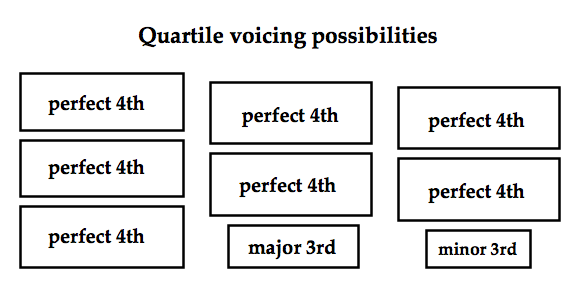

Quartile harmony. Another way to stack pitches into chords is termed quartile harmony. Now our pitches are stacked mostly in intervals of fourths not thirds, although combinations of both intervals in the same voicing are not uncommon. Here's a pure 4th's Two coming to rest on pure 3rd's tonic, major then minor. Example 7. |

|

Hearing the difference between intervals of fourths and thirds? Click it again, no limit clicking we call it here :) So while surely a jazz color (well they all are), we'll also hear the quartile colors fairly often in pop, country and surely surely surely in the western swing musical styles. Next, examine our interval building blocks for quartile voicing construction techniques. Example 7a. |

|

Make sense? So we can do both. Stack 4th's and jettison some TG, or define our chord as either major or minor, by starting with a 3rd. Easy, three choices to rote know. |

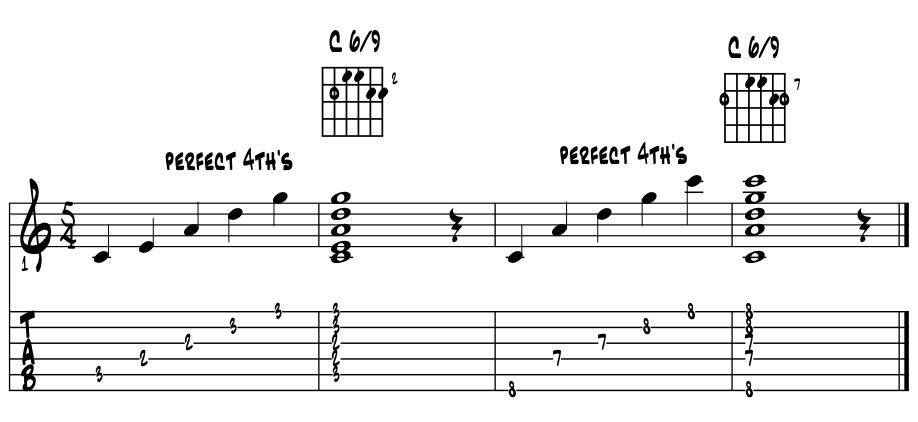

The quartile chords have a special place on our palettes in that they give us super nice bright and tight chord voicings that can easily feature the tonic pitch in the lead. This clearly solves problems for cats who dig to 'jazz up' their chords with colortone pitches and yet need that sense of finality for a last chord or hold in an arrangement. So chord color plus tonic on on top? Quartile to the rescue! Example 7b. |

|

Hear the finality of the last chord? That's home. With the tonic pitch as the root and in the lead, supported by cool colors, these quartile critters lock in our tonal center and can swing with a depth and power possibly unmatched by any other combinations of pitches. Even equal to a 'blues 13th' chord? Man that's a tough one, for both can be true tonic chords and swing just madly ! |

For tonic is king in our American musics, has been since our inception. We theorists call this centering 'tonality' and it all just seems to swing hardest from the center. Click to the '6/9 chords' link for additional ideas and shapes for the evolving, modern guitarist. |

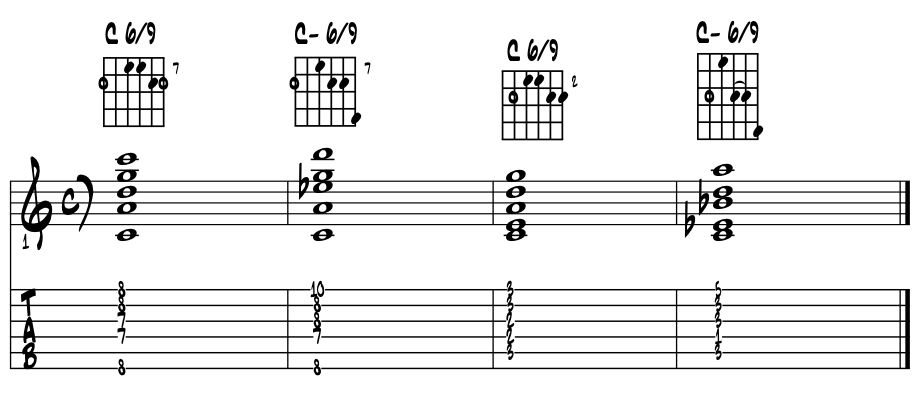

Minor 6 / 9. In the following example, we take one root position quartile chord shape and evolve it from major to minor. Example 7c. |

|

Hear the shifting to minor? Cool. Surely a core skill for the evolving theorist and player. So how do you perceive these two chords? Are they new ones for you? Broad yet restive is my own best description for now. Broad surely as they sound and sit like a meditating Buddha. Restive in that they are a tonic color and thus have sat at the center of things since the days of old. |

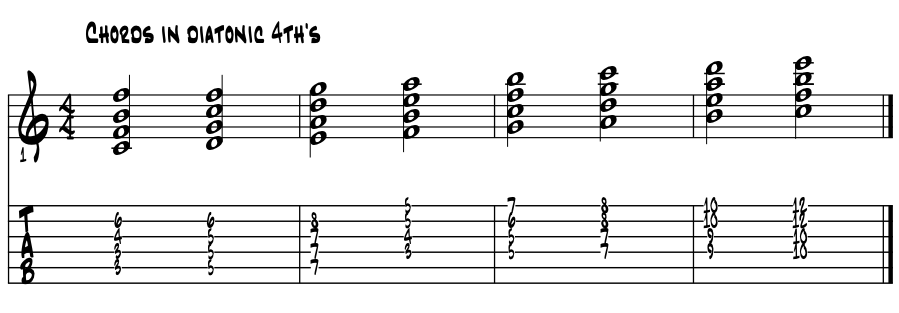

Another quick review. Chords built in 3rd's are by far and away the most common in our American musics. Chords with 4th's usually have additional pitches of 3rd's to round out and stabilize their voicings, keeping the center of things the center. We also can create cool chords exclusively built in fourths, often diatonically, to create unique progressions and entire songs. Examine the seven diatonic, quartile chords in 'C' major. Ex. 7d. |

|

Still in Kansas here? Yea we are but ... there's a twist in the tonal gravity and sense of center. A 'veiling' of sorts that changes our sense of tonic within the diatonic tonality. Leaning modal? Yep. So a new 'kind of blue?' Yea that too :) |

|

How spelling chords can help us. Well, if you were able to decipher the 'how to' to create and spell arpeggios in the last discussion, then the following theory should be be a breeze. For it is exactly the same process plus one. Spelling chords is the letter / pitch basis of playing 'through' chord changes. So for cats leaning towards this sort of improv, spelling is just essential really. For we can first 'guide tone line spell' each chord in the progression, and give our ears an easy way in, a 'correct' way to 'hear and rote learn the changes in the line.' |

Diatonic Euro harmony / inside ~ outside. Since our harmonic abilities originated from Europe, we could benefit from understanding how their music evolved from the 1700's onward. In the emerging compositional style termed homophonic, diatonic theory holds that one set or group of pitches becomes the sole pitch resource for making melodies and the chords to support it within a single song. This group we term a parent scale, such as 'C' major, who's pitches becomes the basis of all things diatonic. The idea of 'diatonic' creates that closed loop of letter name pitches that we spell our chords with. |

In diatonic classical music, everything bolts right up perfectly pitch wise between melody, chords and the arpeggios in between. For the melody lines of Bach, on through the music of Hayden, Mozart and Beethoven, all are supported by harmonies that are created from the same group of pitches, thus diatonic. And when they're not, we theory scholars really want to know why. Good spellers quickly unlock the mysteries. |

|

Non-diatonic pitches. Non diatonic pitches are simply those that are not part of a key center's pitches or parent scale. These non-diatonic or outside pitches, which we oftentimes simply viewed as borrowed from other key centers, can become the artistic points in the music that we scholars use in tracing the evolution of the artists we love throughout their careers. Again good chord spellers can quickly unlock any jumble of pitches. |

Spelling chords ~ a rule of thumb. Think diatonically as best you can then borrow or alter whatever additional pitches needed to support the melody line in the style of music we're making. It's a numbers game really, for diatonic gives us seven, so there's only five left to muse on and negotiate. Please examine the key signature and pitches of A major, with cliche rhythm. Example 8. |

To these diatonic seven we jazz up with the other five. What's your style? Folk? Probably spelling diatonic triads. Blues? Might need a 7th on each chord so need to borrow, so spelling gets tricky. Jazz? Diatonic basis, with modulation, so additional tonal centers within one song. So additional 'sets of seven' for diatonic chord spelling and a new group of five to jazz them up. |

Americana music. And we while we Americana music scholars follow along the same general techniques for discovery of evolution as our Euro brethren, there's one consistent musical color we have they don't, that rocks the diatonic boat if you will. This of course is the blues, whose pitches, while theoretically identifiable, are so often articulated in performance in ways that are a distinct challenge to accurately notate and write down to preserve. |

Is this a problem? No not at all, for the blues is an oral tradition, passed lovingly along from player to player, generation to generation by the cats who work the magic. So without charts, we work by ear. Thus, spelling the chords becomes an easy way to decipher how the blue notes and chords line up. For in the 'blues rub', while there's really no end to the combinations, there' are some set in stone hair raisers, and spelling chords will help to unlock these powers for the emerging artist. |

|

The blues rub. So while children's songs and folk music generally follow this diatonic ( inside ) scale / chord format, any time the American blues colors spice up our music; in rock, country, pop etc., we oftentimes end up in a situation where we cannot seamlessly evolve from scale into arpeggio and create our chords as described in the diatonic process. Oftentimes ...? Then there's a bit of wiggle room here? There surely is and for us theorists, an amen to that :) |

So the idea of the blues rub, simply a situation when our diatonic melody pitch / chord relationship is challenged by using non-diatonic pitches. So again is this a problem? No of course not, but as theorists we surely want to know what's what so as to be able to identify and recreate non-diatonic coolness when desired. For the core freedom of the American way surely applies to all things musical. We simply create the elements we need from their diatonic sources and collage them together to express the art in our hearts. |

|

It turns out that this 'rub' between the pitches can become the actual sounds that can make our hair stand up, when we listen to the cats that know the language and have something to say. For in traditional blues performance, often it's the wailing of one blue note, rhythmically pulsed that connects to the blues within us all as sentient beings, that stands the hair up and encourage the dancers to move. In this sort of testimony, the lead melody line, often the voice, sets the tone. The supporting chords oftentimes do not have this pitch, tuned up the same way, and in there as we say ... 'lies the rub :)' |

Spelling the seven diatonic triads in a major key. So with the above ideas in mind, let's create the rock and the hard spot; a diatonic core, rock solid foundation that never varies in the theory, yet is absolutely bendable to any artistic whim or notion, and of course works in all our key centers, styles, genres and beyond. Layering scale and arpeggio degree numbers with pitch letter names, we line them up to spell our chords. Thinking 'C' major, examine the following chart. Example 9. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 (1) |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 (1) |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Numerical magic. While the pitches are the same, we need to add a way to locate ourselves in the chart to facilitate the spelling of our diatonic triads. We do this by creating numerical equivalents for each of our pitches. In the above chart we see two numerical designations, one for our major scale degrees and a different set of numbers for its arpeggio pitches, named arpeggio degrees. |

By using the numbers instead of letter names, we lock in a set of theory principles that we can apply to all 12 of our major scales. Relative minor too? Yep, relative minor too, and of course all their modes and variations that live in between. Everything? Everything :) |

This simple evolution from pitch letter name to pitch number is an integral part of changing the game and getting one's arms completely around the resource. We need the numbers 1 through 8 or 1 through 15, and move by half step with the sharp (#) and flat (b). Done. |

Scale degrees. Our numbered scale degrees are simply stepwise one through eight and designate each step of our various scales as contained within one octave. Again, #'s and b's move the symbols half step. One, up a half step, becomes '#1' etc. Two, down a half step becomes 'b2' and so on. We can apply this type of thinking to any of our melodic groups, for both their diatonic and non-diatonic pitches. |

Arpeggio degrees. As we evolve our scale into its two octave arpeggio, our numerical pitch representations follow the lettered pitches by skipping every other one. This evolves our group from a stepwise pattern of half steps and whole steps to our arpeggiated grouping based on the intervals of the major and minor thirds. Rote learning. Again, we can apply this type of thinking to any of our arpeggiated groups, for both their diatonic and non-diatonic pitches. And again, the #'s and b's will generally move any symbol by half step. |

The trick. The whole trick to spelling triads with this chart is simply to decide which one we want to spell. And once we decide that, their three letter pitches to build up a chord jump right out of the chart of King Tut. ( Of course using primary colors is a sure help. ) |

The tonic One chord. Well, knowing that most of our songs have chord progressions with at least a couple of chords, and there's near always a One chord, may as well start there. In the key of 'C', a One chord is a triad / chord built on the first scale degree. So, we theorists want to spell the pitches of the triad built on One, in the key of 'C' major. Knowing that, we simply find that number / pitch as a scale degree and then within the arpeggio, we read the letter name pitches to the right to spell its three triad pitches. Which in this case provides the root, major 3rd and perfect 5th of a 'C' major triad. Example 9a. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 (1) |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Easy to see the cornerstone of our chord spelling chart? Cool. Can you find and spell the letter pitches of a triad built on the second scale degree? Two? Example 9b. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Ah, the magic of color to highlight the point of focus. Once we can position the number One above the root of the triad / chord we want to spell, we're golden. Seeing the patterns here? And are are loops yes? Yes, all are loops. Each line has the perfect closure :) |

Chordal building blocks of thirds. As depicted above, we can view our triads as structures built by different sized blocks of the major and minor third interval. Knowing how we stack these blocks will surely come in handy, especially when we add additional pitches, our color tones, to spice up our harmony. Re-examine here the major triad building blocks of 3rd's and rote memorize the interval constructions. Here we focus on the major triad, surely a top choice of pitches for composers throughout the ages. Example 9c. |

|

There's really just a few key shapes for playing these triads as arpeggios across and up and down the strings. Invaluable movable shapes to the cats who aspire to improvise by playing 'through the changes. Common major triad shapes and fingering suggestions. Ex. 9d. |

|

Bit of a pattern forming in this last idea. Did you pick it up? Motion in perfect fourths. Could go on for a while. |

Common C chords. Here are a couple of common C major chord voicings used to create the Americana sounds. Do note the doubling, and even the tripling, of our root pitches in the following example. Example 9e. |

At the piano. Here's a look at the piano keyboard showing the location of the pitches of a C major triad. If you have access to a piano, do try locating other positions of the C major triads by simply noting the location of the white and black keys. There should be seven in all on a full size piano manual. Example 9f. |

|

Where in the music. In every song we play, in every musical style, there's some sort of a tonic One chord somewhere in the tune. It's not always a 'C' chord or a major triad of course, but there's a tonic in there somewhere, that's if there are chords in the song. Tonic chords are usually preceded by a Five chord, as we begin to build up chord progressions. Here's a few Five to One cadential motions. Example 9g. |

Familiar? Cool. And in about 69.059463 % of the time, or 7 out of 10, our tonic chord is also the first chord of the song. It's the Sun center of the song, all the other pitches will orbit in varying degrees around this root pitch and chord. In songs written in either the major or minor tonality, the tonic One chord / tonic pitch is the core resting point pitch that all of the other pitches and chords in the song gravitate to and fro. |

|

Tonic function chords in children's songs and folk music are traditionally speaking, triad based. Players use open chord voicings to create the harmony. American blues chords are predominantly triad based with an added blue 7th, so essential in creating the blues rub from within. Any blues influence to folk or rock will carry these colors right along. While open chords are common, a capo and or barre chords, are often employed to change key centers. |

Pop music will run the spectrum from triads to adding any of the colortones. In surveying the libraries of well crafted songs of artists such as Stevie Wonder, Steely Dan and the Beatles, tonic function One chords encompass the full spectrum of what is available. In the Latin bossa styles and American jazz music, we'll find a full spectrum of tonic harmony also. |

Author's note. If by chance there is no tonic chord in the music you dig, and or, even aspire to play, then chances are good you do not need 95% of the info of this book. And there's really just a pair of way advanced ideas that relate to non tonic musics. One about time, musical time and phrasing. And one about looping our ancient pitches in a new symmetrical way. |

Chord type / tonic. We theorists also designate the One chord in a major key as a chord 'type.' Chord type is a sort of shorthand for cataloguing chords that function the same way throughout our various styles of music. Based on the third and seventh intervals of a chord and mostly a jazz concept, the chord type of our One / tonic chord is one of three categories of chords. |

The 'supertonic' Two chord. Let's locate and spell the Two chord in the key of 'C' major by using the same process and chart. Thinking 'C' major, our second scale degree pitch is 'D.' To spell the Two chord we simply find that pitch in the arpeggio and read to the right to locate its pitches. Notice again the shifting over of the arpeggio degree numbers, as the pitch 'D' is now the designated root pitch. Example 10. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 ... |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Ok with the process here? Keep trying and you will. Is working this chart all about sliding these numbers around? Designating our start points with One followed by Three then Five? Yep, kinda light on the magic for such a game changer huh ? Positioning to designate the number One / 1 as the root pitch, of the triad / chord we want to spell. Read letters to the right. 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 and close the loop ... :) Yep, in this chart form, it's just that simple really. |

Common D minor chords. Here are a couple of common 'D' minor chord voicings used to create the American sounds. Example 10a. |

Such clarity of harmony with voicings created using just the three notes of the triad. No mistaking the minor sounding quality of each chord. These last few shapes work fine in folk, blues, 70's rock and on into pop and jazz. They're also the core, tonic harmony for the ancient Dorian mode, who's melodies go all the way back and then some. |

Where in the music. We can find the Two chord through any of the styles of Americana music. When the bass story line wants to walk up between One and Four, Two is an easy fit in between. Once Two ( ii-7 ) begins to cover for Four in cadential motions, in 'C' major; the triad 'F A C' becomes' D F A C', and the stage is set to walk the bass. When well crafted, the walking bass lines can and will add swing to anything. The Two chord has historically been a huge part of this evolution. |

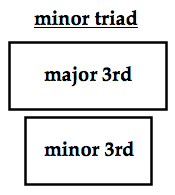

Triad blocks of thirds. Our minor triad is centered on the minor third interval between root and 3rd. Then a major third leap to locate its 5th. Is this an 'interval flipping' of the major triad? Yep. And diatonic Two is always minor when generated from a major key? Yep. Always. Building a minor triad. Example 10b. |

|

|

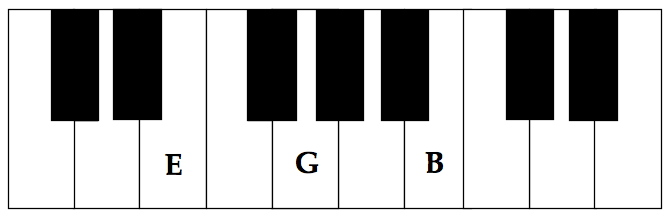

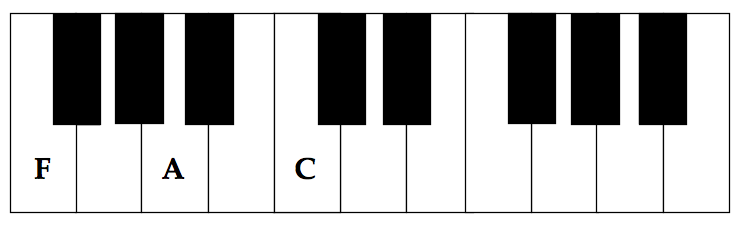

At the piano. Here's a look at the piano keyboard showing the location of the pitches of a 'D' minor triad. Find this at a keyboard as resources permit. Ex. 10c. |

|

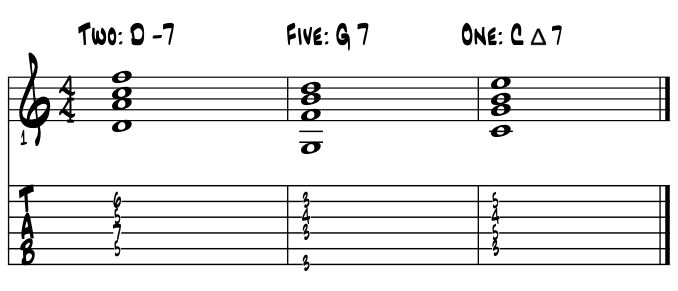

Two chord type. The Two chord also gets a place in our discussions of chord type. In this theory, we simply seek to simplify things as best we can, so as to free ourselves for creating the art. In Americana jazz from roughly the 1930's onward, as the tempos got brighter and brighter towards the blaze of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and pals, the sleeker Two / Five harmonic motion begins to dominate cadential motion. While Four remains a true destination in near every song, we'll jazzily, and quite more rapidly, get there via Two / Five / One. |

|

Chord type goes right along with ideas of using numbers to represent pitches. As one set of theory numbers creates the template for all 12 major and 12 minor keys. So once the theory is learned by the numbers, we simply adjust for the right pitches to create each key center. And key color? Colors of keys? Of course our keys hold different colors, we each just have to discover what each means to us individually. Especially so if a voice is in the mix. |

Where in the music. As we theory name the Two chord the 'supertonic', in its whole step proximity to One, we can commonly find it a couple of places. In this next idea, we build chords on our first four scale degrees and create the essential, diatonic stepwise motion. The last bar is a cadence using the diatonic Two chord. Note the the Roman numerals added, to identify the diatonic chords in this next idea. Example 10cc. |

|

Sound familiar ? Cool. Just our stepwise, diatonic chords heading to Four. With some added color with a booboo in the last measure. There's something goofy with that tonic 'C' chord. The tab indicates a bit of a stretch too :) |

Songs. Bill Wither's classic 'Lean On Me' is one classic song using this diatonic stepwise motion to perfection. The Two / Five is common throughout the literature but surely an essential cadential motion in American jazz. |

|

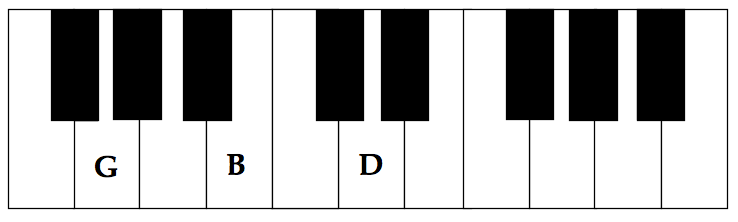

The 'mediant' Three chord. Let's find and spell the triad built on the Three in the key of 'C' major. Our third scale degree pitch in the key of 'C' major is 'E.' Find that pitch in the arpeggio and read to the right to locate its triad pitches. Our diatonic Three chord is always a minor triad and also termed the 'mediant' chord in classical theory. Example 11. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

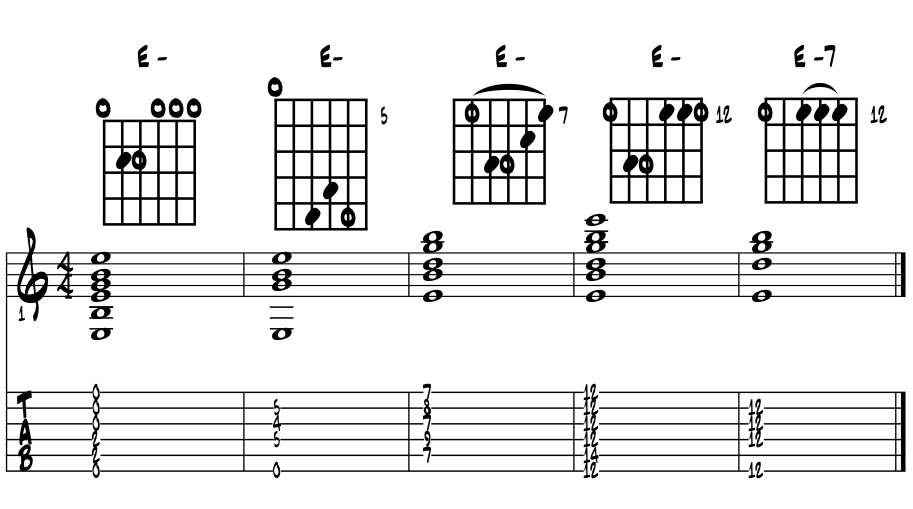

Common E minor chords. Here are a couple of common 'E' minor chord voicings used to create the Americana sounds we love. The open chord is in the folk traditions. The second shape is a handy three note movable chunk with the root on top. Of the two barre chords, both are of course completely movable. |

The last chord adds the diatonic 7th degree, which up on the 12th fret just might not be all that handy as a root position 'E-7', but it also is easily moved down the fingerboard to different root pitches, and is a keeper. A rather an essential shape in blues and rock and beyond, this 'E-7' voicing helps cover the bebop jazz right up through the more 'pop jazz' of Van Morrison and forward through to today. Example 11a. |

|

Recognize any of the shapes? The first open E minor is the first most of us learn. Hangs very cool with the open A minor and often paired with 'G.' The middle barre chord shapes are classic 70's. The last voicing is a key blues and jazz voicing. |

Triad blocks of thirds. Like our diatonic triad built on Two, the Three chord is always a minor triad. From our root pitch we simply stack a minor third interval then a major third on top. Example 11b. |

|

At the piano. Here's a look at the piano keyboard showing the location of the pitches of an E minor triad. Find this chord at the keyboard sometime if necessary, pretty powerful. Example 11c. |

|

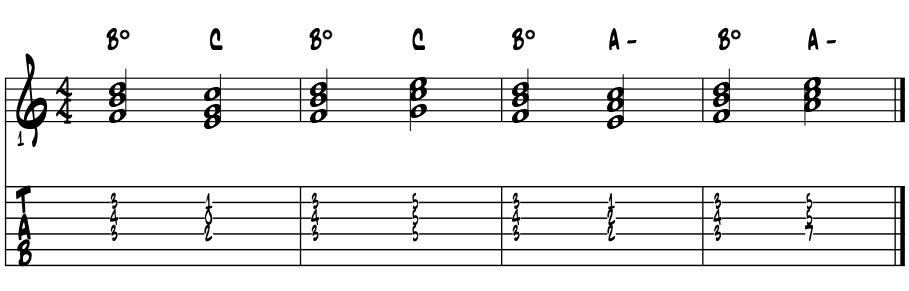

Where in the music. Initially there's probably one key spot where we'll find our Three chord through a range of styles and songs. In moving from One to Four, we often land to pause on Three, as a passing chord, creating that Americana gospel effect. |

The second half of this next example is a realization of the essential Three / Six / Two / Five motion. While mostly a jazz progression in today's terms, its cycle of fourths motion reaches somewhere stylistically into everything we historically have a record of. This type of historical depth in a chord progression generally means there's a ton of songs that use it. Example 11d. |

Where in the music. The easiest song to hear Three working its stepwise magic between One and Four just might be in the folk / rock classic titled 'The Weight', by Robbie Robertson. |

|

Wendy Williamson. Years past here in town there was a cat named Wendy Williamson. Back during the pipeline days, Wendy surely was one of the kings on the local gig circuit. I was lucky to hang with him a wee bit at the community college where he mentored everyone and anyone about anything music. |

On more than one occasion he quipped to us in describing jazz harmonies and motions, that 'everything can be thought of or turned into a Three / Six / Two / Five chord cycle. He then would sit down at the piano and show us just how it all could be done. With Wendy's piano mastery, hearing surely was believing. So just a thought to ponder for those so inclined; that everything somehow can be though of as a 3 6 2 5 motion :) |

An evolution. Here in Essentials, it is firmly believed that this 3 / 6 / 2 / 5 / motion was the catalyst that inspired the next evolution of Americana jazz harmony. It first appears on record in 1957. Mr. Coltrane? Yes. |

The Four chord. Next up is to find and spell the pitches of the Four chord, which in a major key is diatonically always a major triad. Theoretically termed and identified as the subdominant, from the following chart we can quickly discover that the fourth scale degree pitch in the key of 'C' major is the letter named pitch 'F' natural. Finding that pitch in the arpeggio and reading to the right, we locate its three triad pitches; root, major 3rd and 5th. Example 12. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Common F major chords. Here are a couple of the common 'F' major chords used to create the Americana sounds. Again the formatting that these shapes generally follow the style evolution. Example 12a. |

Triad blocks. Our major triad built on Four shares the same construction as our One chord; root, major 3rd and perfect 5th. Example 12b. |

|

At the piano. Locating the pitches of an 'F' major triad. Example 12c. |

|

Where in the music. The Four chord is essential in so many ways in the Americana sounds. It's hard to know where to begin. That Four is the secondary resting point, second only to its tonic One, is probably tops of its importance to us and its abilities. As most musical stories start somewhere around One and then figure a way to get to Four, where we can get a breath of respite before moving on and eventually heading back home to finish our story, verse etc. |

An essential gospel color, motion to Four can lift our spirits like no other. In the blues, the Four chord is fully 1/3 of the core 12 bar form. The One / Four / Five progression, in both major and minor, supports how many songs? Having the One / Four and Five triads / chords diatonically generated in each key center gives us the basic six chords of folk, blues rock and country. The diatonic 3 and 3? Yep. |

Four becomes Two / the Two chord type evolves. As Americana music evolved over the decades, while the Four chord has retained its preeminent place in the most of our styles, in jazz progressions, the sleeker Two chord better accommodates the brisker tempos and the wider range of modulations available to the evolving jazz artist. And while Four is still a popular modulation destination in jazz, chances are we'll use a Two chord to get there :) Examine how our major triad built on Four becomes a minor 7th chord built on Two. Example 12d. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

So which to use, Two or Four? If the song is mostly diatonic, Four is most common. Stepwise motion? Two comes into play. Need a stronger sense of key change? Either really, but Two / Five in brighter tempos. We just have to look at the spot in the music and decide what's needed. And while style plays a role in choosing, as theorists it's just good to know what's out there, even generate new components, so to have a few choices for composing our ideas. |

So might we apply this idea to other chords as well? Simply change the root of the chord by finding the next lowest pitch in the arpeggio? Or even the one above it? Absolutely. For we have the chord inversions discussed above, that process in which each of the three pitches of the triad can be the lowest pitch of the chord. Remember about bass line stories ? |

Quick review / spelling triads. We simply rearrange diatonic scale pitches into its arpeggio pattern of major and minor 3rds, then create three note segment blocks termed triads. Spelling the letter names of the triads and chords is a process we should learn and rote memorize. All 12 keys major and minor? Eventually, but surely in the keys you mostly hang in. |

Once mastered, perhaps share this theory magic with your friends and bandmates, for it sure can makes things a lot easier when everyone in the group is hip to the changes. Here's a chart to review the letter name pitches of our first four diatonic triads in the key of C major. Example 13. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

C |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

scale pitches |

C |

D |

E |

C |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

C major triad |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

D minor triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

D |

F |

A |

. |

E minor triad |

. |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

F major triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

F |

A |

C |

Getting the hang of this chart and spelling out the diatonic triads? There's more we can do with this chart; easily explore the arpeggios, added color tones, altered chord and color tones, help create substitutions etc. |

Projecting / spelling chords in 12 major keys by numerical equivalents. That we can recreate all of this diatonic harmony equally, that all is in tune with one another, from each of the pitches of the chromatic scale is thanks to the equal temper tuning of the pitches. That magic of the 12th root of 2, or 1.0594631. Dividing the 12 pitches equally within the octave span, '2.' While we're using letters to keep track of things at this juncture, we eventually can choose to shift to using our basic numbers, our numerical equivalents, to represent any pitch position; melody, arpeggio, chord position, colortone and chord progression. |

Of course there is a potential ton of this type of numerical thinking in our theory studies. Where numbers replace letters and math and music continue their eternal dance. Can all things pitch can be numbered, thus generating new avenues of exploration based on numerical possibilities, i.e., patterns, sequences, cycles etc. ? Once numerical patterns are established, our own creative nuance of articulation, phrasing and melody brings the potentially more sterile mathematical possibilities back towards artistic life. |

Numerical equivalents / what we gain. Our learning curve can dramatically flatten out once a thorough numerical sense of the theory is achieved. It's actually kind of shocking in a way. That the theory is essentially so numerically simplistic while its are implications not only colossal, but probably artistically limitless too :) |

So where in the music. The 'numbers perspective' can be used anywhere in our music. In children's songs, the folk styles, and most blues and rock and pop and beyond. And while this type of numerical thinking is not predominant in these styles, as there's usually just a few chords used in songs, knowing and hearing numerically can open up a wider range of choices for the curious, modern guitarist to consider. |