~ EMG jazz guitar method / B. A. ~ ~ thinking with all 12 pitches ~ . |

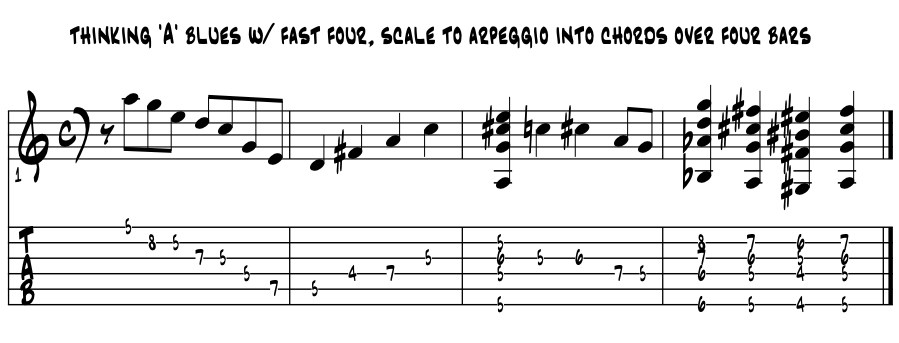

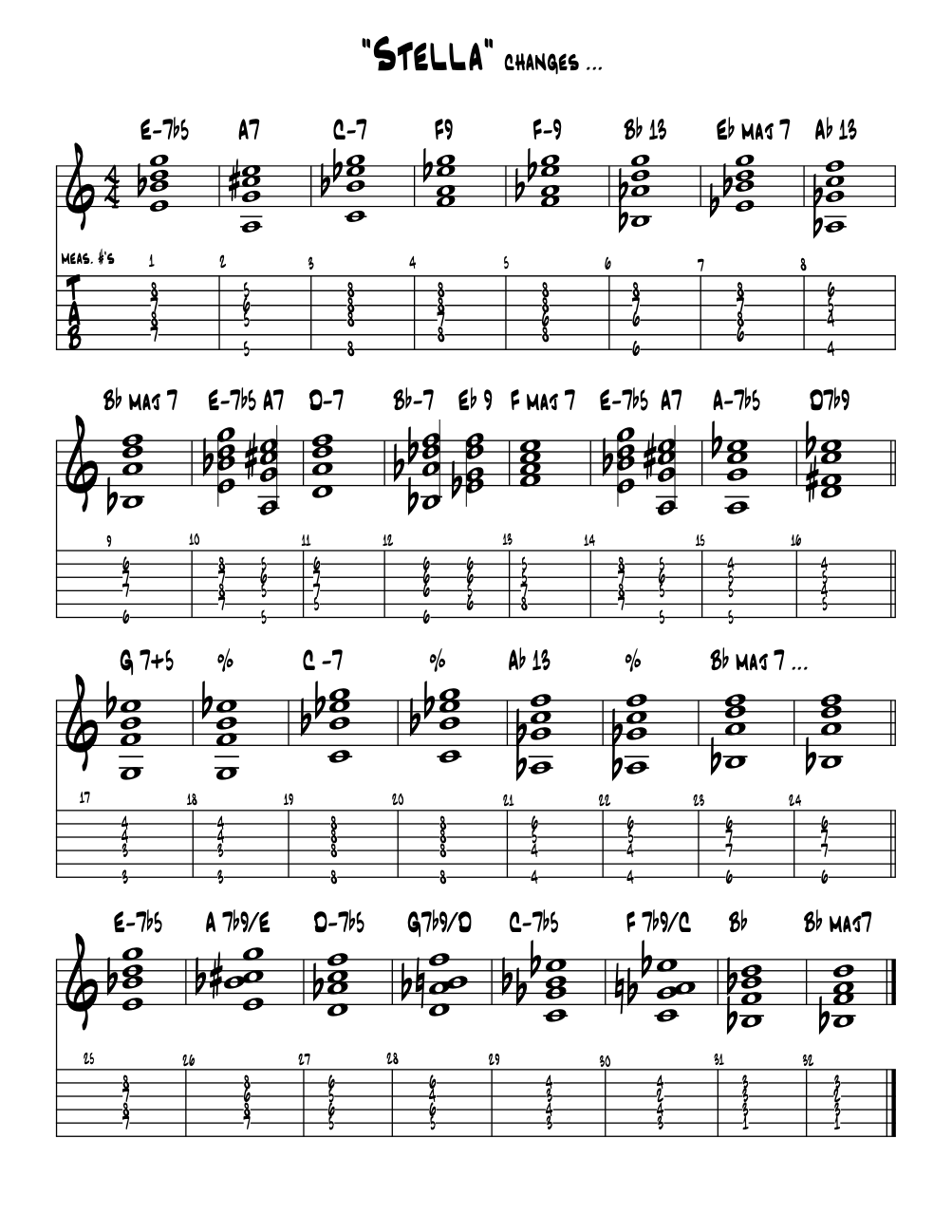

In a nutshell. In this guitar method e-book the basics of Americana jazz guitar are developed through three exciting pathways of discovery. The first pathway is the blues, a deep root in Americana, studied with the steady clicks of a metronome. For by mastering the 12 bar form we can readily develop its initial 'three chords and the truth' harmonies to eventually include a chorus or two of pure bebop changes, 'chock full of changes' and thus, all sorts of melody / improv options and challenges as the gaps between the changes slim and tempos accelerate. |

And with 12 bars, three / four bar phrases, we learn the powers of a four bar phrase and the compositional form of many jazz songs. Through in the blue notes, and that all the chords are 'V7' harmony, we learn chord substitution and get them under our fingers, knowing these same substitution principles will also work through the Americana jazz 'standards' songbook. |

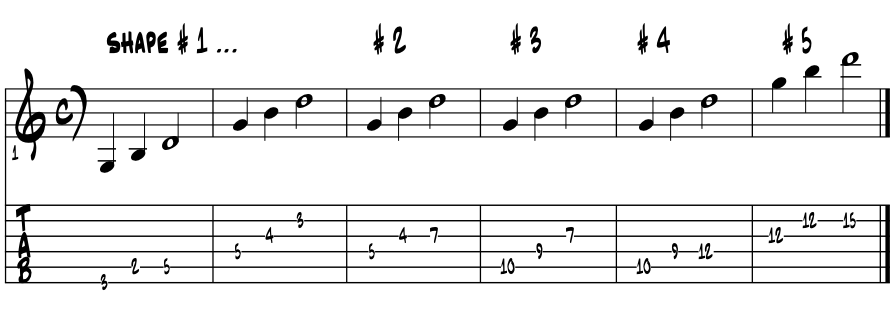

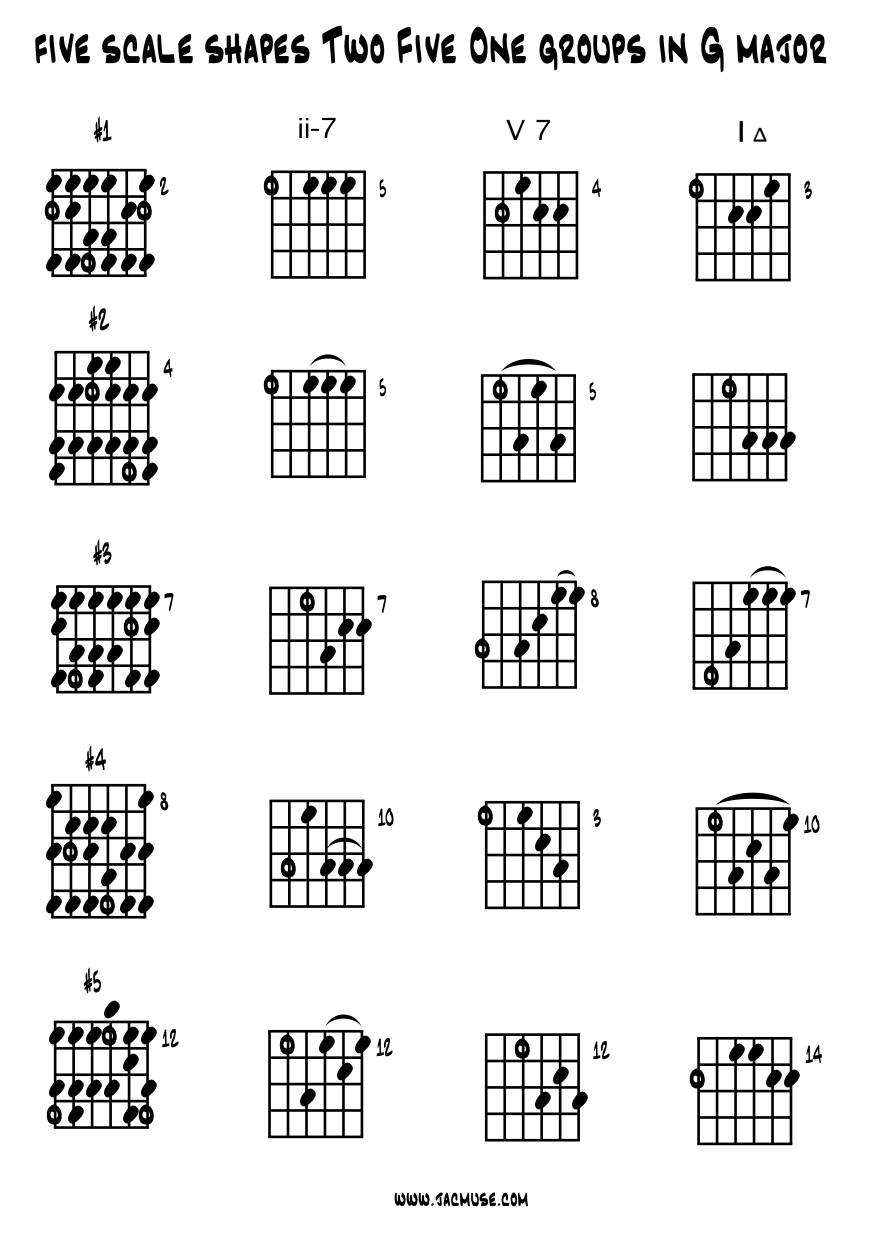

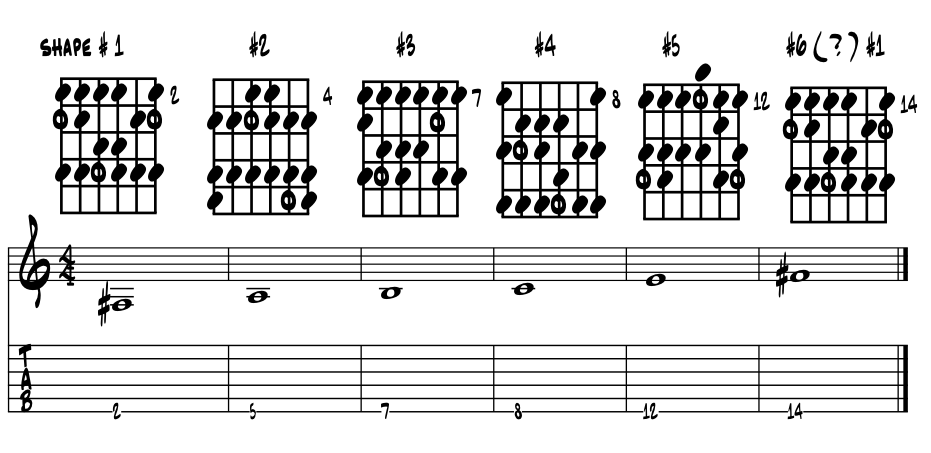

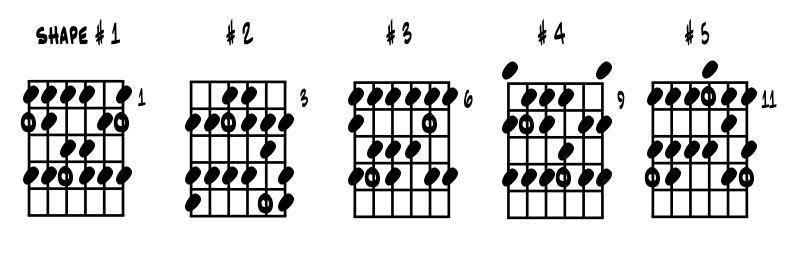

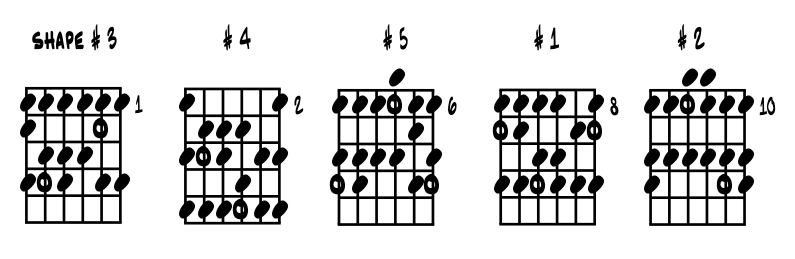

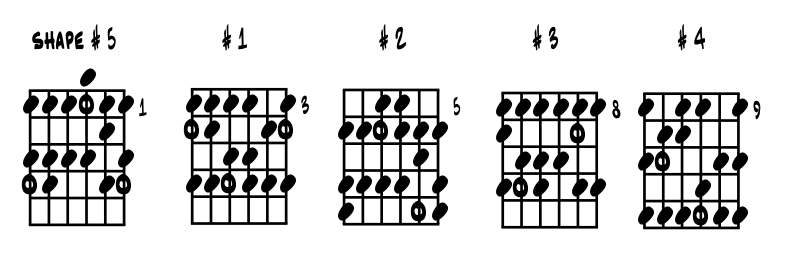

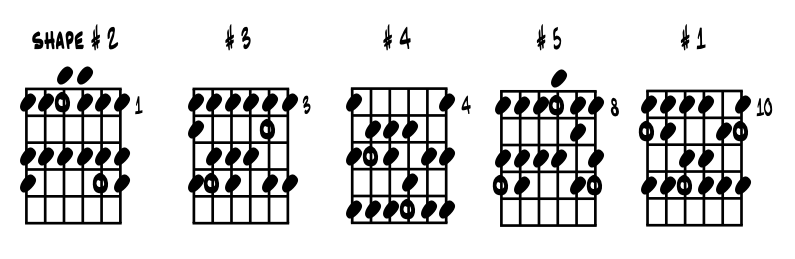

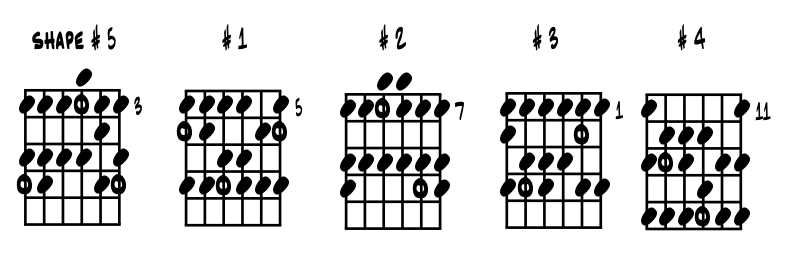

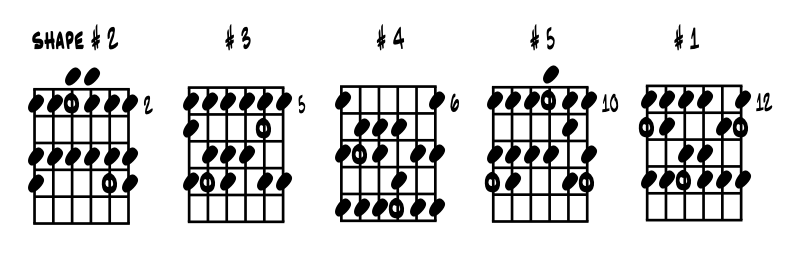

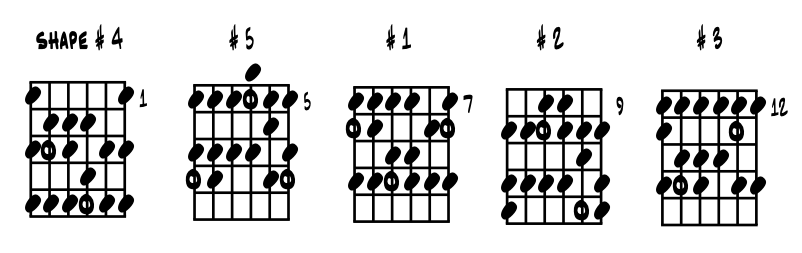

The second pathway leads to understanding how the pitches of a guitar are 'built right in' for the relative key centers of 'E minor and 'G' major, the ancient pairing. Five fingering shapes cover these groups of diatonic notes over first 12 frets and create a closed loop. |

|

In these five shapes are contained the diatonic pitches of our most common scales, modes, intervals, arpeggios, chords and color tones. In jazz guitar, near every shape we learn is a movable one; scales, arpeggios and chords, and this is a big help getting through the popular keys and eventually to all 12 of our diatonic key centers. |

Jazz players improvise. Shedding these five shapes forms the basis of the jazz guitar studies in this primer. For in working through the chores; first stepwise motion for the basic pattern, then intervals, then 7th chord arpeggios and their chord shapes, they combine to give us the nuts and bolts components to improvise jazzy lines from right out of thin air, actually from our own imaginations ... and a little help from Muse. |

|

For when we 'theory study' the improvisations of the master jazz artists we each love, and look to discover what makes their music so happenin', rarely is it ever just one component, but a combination of elements knit together in their own way, and these essentials elements are developed from these studies. |

The third discovery pathway is for understanding the physical nature of time in music. Its been called 'swing' in Americana musics, especially jazz, since the beginning of this style now. There's a solid physical 'pull' to it, to feel and clap right along to. Once this feeling is in place, development of the timing and rhythms of Americana musics with guitar becomes unique challenge we guitarists accept. |

"Space has its own groove and swing." |

wiki ~ Wayne Shorter |

All artists that jazz up their musics share in this boundless excitement that jazz music creates. For with the 'jazz it up' upgrade, we get to more liberally use literally everything, all the musical colors our instruments can create. In this primer, 'everything' is brought together under the long term shedding and understanding goal of 'anything from anywhere.' |

The ancient method. Really ? Well in a couple of ways yes. Knowing that our fretted instruments have had a go at equal temperament all along, and that the lute itself eventually becomes a six string guitar, we carry the Euro traditions of shedding into the Americana world of jazz when wanting to master the fingerboard through all 12 of our paired major and minor key centers. And while there's lots of variations, the basics of the guitar remain the same. That in standard tuning, it is built and tuned to the 'G' major and 'E' minor pairing of key centers. So in our shedding to master the resources we can combine all of the cultures and styles into a sequence of shedding to master the fingerboard. The method here based on BA college curriculum can go like this. There's five shapes that link together to form a loop of the relative major / minor pairing of 'G and E' pitches that covers the first octave, or 12 frets of our guitars. Above the 12th fret it just over again. Once in place we run each shape through the interval studies. Then work the diatonic arpeggios for each shape to include the triad and 7th. These arpeggios become chords, which we then can 'type' as a '2 5 1', jazz music's historical bread and butter changes and chord progression. Learning the five 'looping' shapes in sequence allows us to start our numbered group on any one of the five; 1 2 3 4 5 / 3 4 5 1 2 / 5 1 2 3 4 etc. And if we follow our numerical pattern up the fingerboard from any starting point in the loop, we can find all the key centers up and down the neck. Likewise, once the five shapes are solid, with some minor shifting we'll get all 12 key centers in a localized' position anywhere on the neck. This built in magic is essential for jazz guitar as tempos brighten and we look to create improvised melody lines through the chord changes of a song. For bebop leaning artists, mastering the five shapes in localized positions is is highly and soundly recommended :) |

|

Tunes. For jazz players learning to improvise, learning tunes is like ... everything, so ask your mentor for suggestions. It's melody and original groove, bass line story and root motions of chords, the chords and of course it's song's poetry; the lyrics and hook, to nuance our phrasing of the story, all combine to strengthen all our musicality while giving us songs to perform. For each new melody under our fingers and in our hearts brings us a new motif or two that'll end up as a riff somewhere in our improvisations. |

|

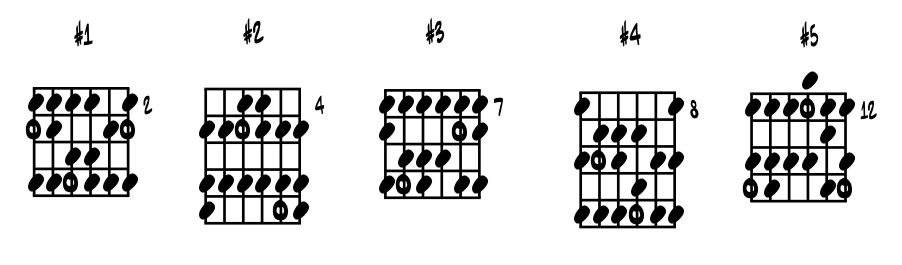

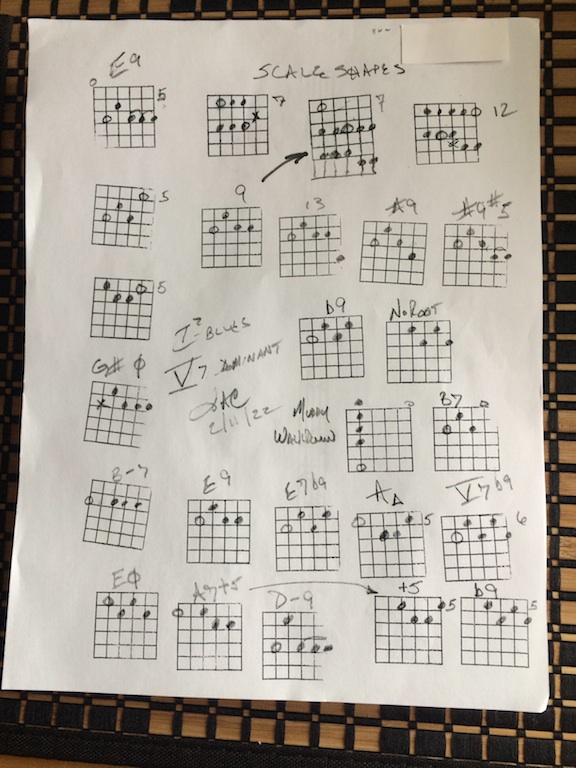

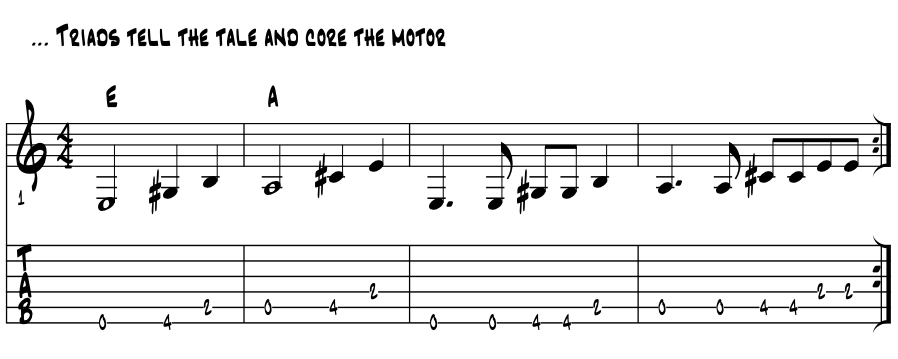

Triads, a first idea ~ five scale shapes. In this next idea, the 'G" major triad outlines its range on our fingerboard. As most of this jazz method is in the relative keys 'G major' and 'E' minor, these pitches and their major triads are some of our initial reference points on our guitars. Find these triads on your guitar. Example 1. |

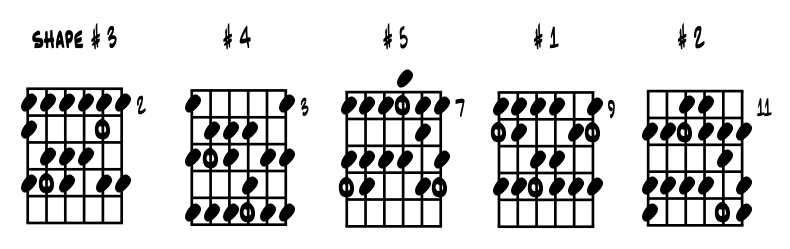

In my era of jazz guitar education, 1980, there were five relative major / minor scale shapes from which all else ... (?) ... flowed and followed. Locating these 'G' triads begins our learning process for each of these five scale shapes are based around the 'G' triad pitches. Established in books by the jazz guitar kings of those days, these combined shapes form the academic basis of much of what follows and help foundation this jazz guitar method. Now ancient, they look like this. Example 1a. |

|

Look at all those black dots ! Lotta doubling there :) And the open dots? Those are the 'G' notes. Combine these two examples and yep, that's the whole tamale for the first year or so of diligent jazz guitar studies. |

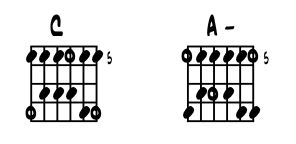

'Jazz concept; the shape of a chord brings a lick too.' This 'theory / in practice / jazz it up' concept idea and format fits for all the styles of Americana, so any song with chords. In creating lines and spaces in writing out idea or improvising, a flip side of generating ideas from any scale shape is to use any chord's shape of pitches ... to generate a riff, a single note line idea, even run its whole scale shape, then refine it into something musical for you, make it your idea, to jazz it on up :) As this evolves, we can learn to play a chord, then find a melody idea from it, then move to the next chord in the song's progression etc. Maybe the most common is this first one, uber popular movable major triad and groovy '1 2 3' fingering shape. Starting here with a few chord shapes in root position, generating riffs and thinking mostly in 'G' and 'E', our built in keys. Ex. 1a. |

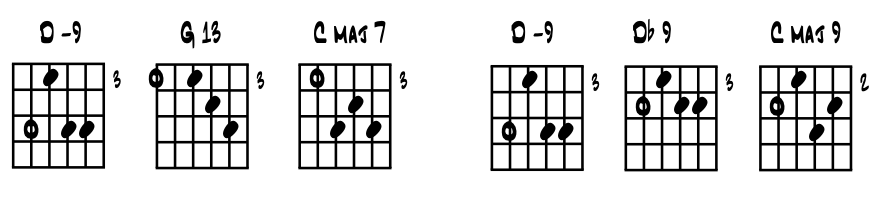

Here are a few more chord shapes generating a motif, leaning more jazz here with added colortones and no doubling of pitches. Example 1b. |

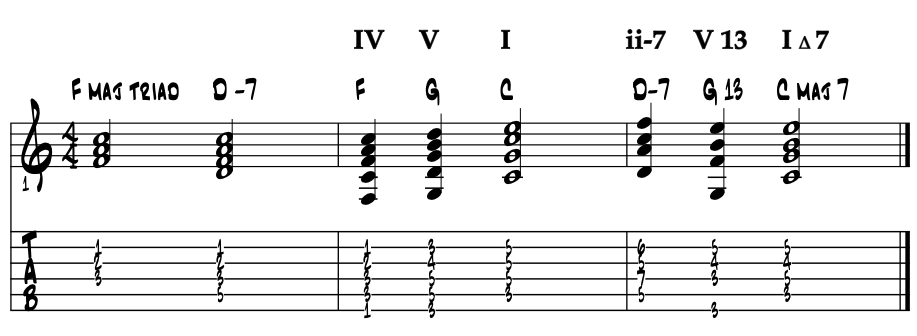

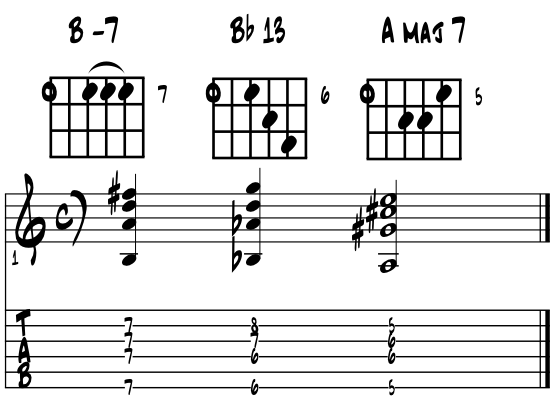

'Shapes in progression.' Chord shapes generating riffs right on through a common jazzier chord progression; the Two / Five / One. First in 'G' then 'C' major. Ex. 1c. |

'Fit's like a glove. As this idea of chord shapes generating melody ideas and riffs comes direct from guitarist Jerry LeVeane during PSUC formal music schooling, we'd be remiss here to not also include a classic Jerry quip ... that it 'fits like a glove', to describe some monster lick he comes up with based on a chord shape. Here's a classic chord shape from those days, so the early 80's, when the 'E9' funk chord ruled as the divebar dancefloor filler chord of em' all :) |

In true "LeVeanian" fashion. A lesson with LeVeane would sort of go like this; 'what can one chord shape, in this case a dominant 'E9' chord, generate for a curious cat.' Here's the results on paper. Example 1d. |

|

Quick review. Using a shape to make a riff works can work with every chord shape, from every style, in any groove. So try it a couple of times with whatever is under your fingers today, see if there's not something here for U, especially knowing they'll be new chord shapes coming along in the future; explore. Author's note. This physical magics knows no bounds, talent will always find a way to make it happen, and this shape magic goes all the way back. How the chord shapes come along with songs, and the new ones we learn along the way, is really up to each of us to discover yes ? That said, knowing the theory of a shape and how it fit's in ... that's also the principles we can chose to explore. And combined ? Well that's the whole tamale n'est ce- pas ? |

"Learn the rules like a pro so you can break them like an artist." |

wiki ~ Pablo Picasso |

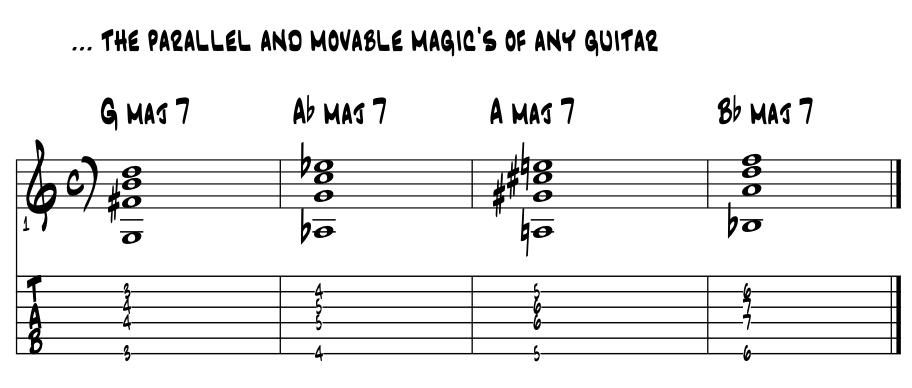

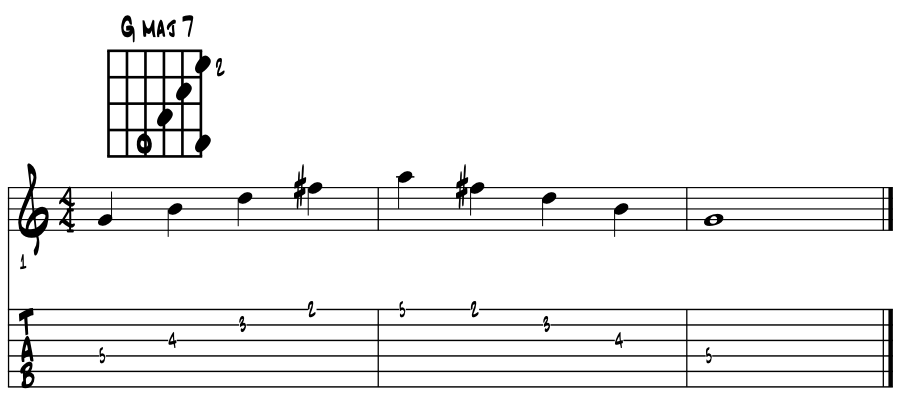

Everything is movable ... in it's own way.' While the above shapes look notey, and they are, as we look to exhaust whatever might be in 'G' in each nook and cranny, know that they are completely movable. Up and down, to cover the other 11 key centers. So there's only these five to master, and while still a handful, it's only a handful. Likewise, every lick, scale, arpeggio and chord we shake loose from each of the these shapes is also movable up and down sometimes even across the strings. This 'everything is movable' is the great facilitator of learning jazz guitar and it'll apply to everything we learn. Everything? Well yes, at least till all this is mastered. The components of jazz songs often move around a lot; moving key centers, chords, arpeggios, borrowing pitches. So even just having five shapes covers a ton of ground when working through the literature. For example, this 'G' major 7th chord works fine in songs in 'G' major. It also feeds the bulldog for songs in 'Ab', 'A', 'Bb' and beyond. Example 2. |

|

Need to jazz up a folk rock ending ? And there it is. |

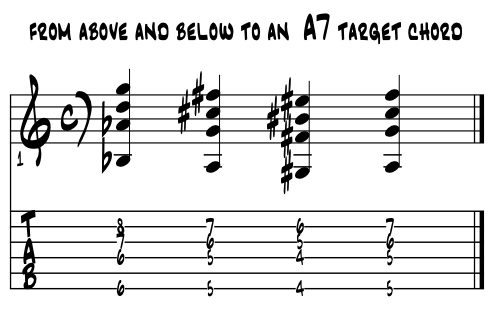

'Half step lead in' technique. Among the first licks to add in to jazzing up our musics, most any note and especially chords, is to move by a half step to get there. For example in a blues in 'G', we'd have step into our 'G' from 'Ab', a half step above. Or from F# of course, a half step below moving up and resolving to 'G.' Example 1. |

|

Drive the rhythm and groove. Ain't nothing that'll bring the smile and to tappin' of Americana swing rhythms like a well placed 'half step lead in.' |

|

Jazz guitar in theory. Those that find their way to jazz guitar inherit an opportunity to understand and utilize the full spectrum of our modern resource; 12 pitches equally tuned, equally capable of centering a full diatonic palette of colors while encouraging any chromaticism between pitches. So key center balance and form with flashes of its blues and beyond too. That the improv nature of jazz encourages the 'borrowing' between diatonic palettes coupled with the modulatory nature of the literature gives us full range of challenges. |

Throw in brighter tempos, soloing through the changes, and jazz's inclusionary nature of style and form, a library of a couple of thousand songs, and we create a curriculum of discovery that can easily span a career's worth of study and creative energies. Then there's the shedding to get the music under our fingers and sharing the joy of working the magic in creating community. |

This jazz guitar method as presented here is a collaboration from players I was able to study with early on. Most of what follows is rote learning of how the instrument provides the 12 equal tempered pitches that create our blue notes, scales, arpeggios and chords. What makes music jazzy include; rhythms, time and swing, color tones and the further divvying up of the diatonic pie, and playing with the expectations of where the music 'sounds like it is going.' |

This method is combined from a few sources that recommended similar approaches to developing the resources. Segovia from the classical side, Joe Pass and Johnny Smith for scales and arpeggios, chords from J.S. Bach, Dr. Miller and Ted Greene. Beginning improvisation and chord melody ideas come directly from Dr. Miller. Near everything included is in root position, thinking from the root pitch, there are links in the following discussions to inversions of various lineages and points beyond to lost worlds. Just kidding :) Explore as your own curiosity demands knowing that ... 'if we think from the root, we'll never get lost.' |

|

Jazz guitar and swing. And while teaching someone how to swing is tricky, teaching what swing is, the physical sensation of what 'swing in musical time' feels like for us, is a fairly easy thing to do. We each of us then just gots to find our own way to work the time magic, which generally means working a bit, or a lot, with a metronome. Learning the swing feel of the monsters we dig that came before us, and then making it into our own unique way to swing, is the tried and true method, and is for all of the fine arts really :) |

"Learn your horn, forget it and play jazz." An idea of the iconic jazz artist Charlie Parker, who sat right in the middle of a blistering groove and revolutionized the artform in the 1940's. This guitar method is to 'learn your horn.' And even to play some of Parker's bebop style jazz, surely a most difficult of challenges for a modern guitarist. Thus empowered, when we apply our jazzy improv ideas and timings to a song of any style, there's just a lot of ways to put our own signature on it, make it our own to share. For jazz guitar is chock full of personal challenges, that when met, strengthen our character as musicians. A rather exciting music to behold and share, jazz music is created by an incredibly exciting thought process coupled with an exhilarating physical sensation of pure joy when performed. And that we get in one sense to make it all up as we go along, ices up the cake nice :) |

Jazz guitar fingerings. This idea of 'learning and forgetting' might also apply to fingerings for learning the various jazzy colors. For while there's some definite ways to finger certain elements, retain the flexibility to say to yourself; 'this lick is unplayable with my normal fingerings.' Then find your best way to play the phrase. Four fingers for four frets. This is historically a classical approach and covers a large bit of jazz ground too. The basics looks like this.

While 'four fingers covering four frets' is a basis that covers a wide wide range of jazz guitar licks yet ... |

Decades ago now a true friend here in town called me and invited me to come over to behold our favorite jazz guitar player perform on video cassette, that they found in the $1 bin box at the video rental store. An hour or so later we both were thoroughly stunned by the myriad of different hand / fingering technique's that this jazz guitar master utilized in getting out their ideas. Rapid one finger horizontal fret and vertical string moves, stopping anywhere for a four finger four fret lick, then thumb over the top for root pitches of chords, an amazingly facile right hand pick hold method that we'd never seen before, and a blurring left (fret) hand we never thought could move that fast, you get the idea. Moral of this story ? Whatever works, works. And we'll find a way to play the lines. |

Advanced jazz music. Chances are if you love jazz music, you'll dig the bebop style of the 1940's. And at some point start to play it. Mentioned above with Charlie Parker, these original bebop lines are saxophone lines, so they've a whole different challenge to sound out when played on a guitar, or any stringed instrument really. Horn to strings is a big technical and technique jump when moving the lines over. Same could be said for chord voicings with piano. There's always a way, we just got to find it. |

|

Technique is important of course but there will be times when a 'proper' sort of fingering, like four fingers four frets just might not work, so we have to adjust and be flexible to the music and its own unique performance demands. Finding a way to play a lick of music correctly is going to simply mean playing the lick successfully, in time and in tempo. And rote learning that fingering for that one lick. Again, bebop lines, often chromatically enhanced arpeggios, are one example of this 'solve this puzzle this way, and play it this way every time.' |

Ah yes, these musical puzzles ... ? Yep, for those so inclined yes, it's all just a series of puzzles to solve. Theory, composing, fingerings and beyond. |

Evolution of the jazz ear. So much of a players evolution into jazz guitar, at least academically, revolves around how we hear the music. For what an artist will 'accept' as a workable color, in common musical situations, can energize the learning. And the lion's share of this 'evolution of the ear' revolves around V7, the dominant chord, and all its potentials and possibilities to create real tension and obscure the tonal and artistic direction of where the music is going. |

For sure there's a lot of coloring we can do with any and all chords, but V7 has its own systemic evolution allowing for near endless substitution. When we add in the evolution of jazz styles into this mix, that a V7 type of chord eventually becomes every chord in our progressions, there's just no end to the machinations of color combinations for the impassioned artist. |

|

And surely style, and 'style / genre of a ___ ', plays a role in all of this. Often being historically 'correct' means a 'D7 chord is a D7' chord. Dixieland players are probably not looking to employ tritone subs or other fancy b2 / 'b9' colors in their weave. That is, if they want to sound legit as a Dixieland guitarist I'd imagine. Just as Bop players will probably not use an open 'C 7' chord too often when heading to Four. Click off to examine the evolutions of V7 through some of its basic historical and theoretical 'jazz it up' magics with V7 chords. |

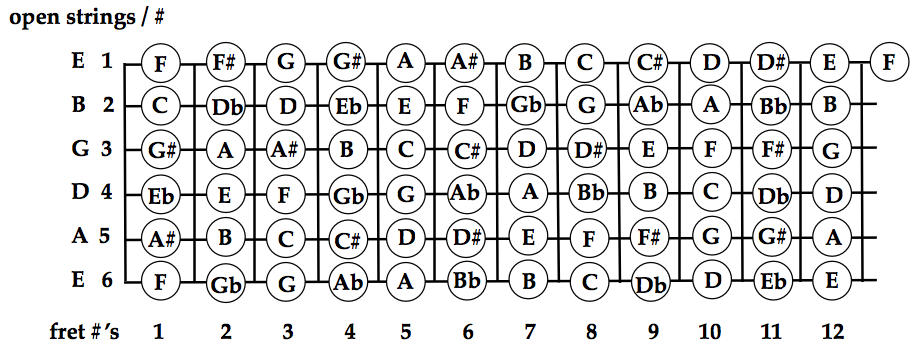

Pitch letter names. Leaning jazz ... ? No better time than the present then to learn the letter names of the pitches. Rote learn them up and they will be yours forever. In some ways, it's a sign of respect for the art and for jazz, today beyond just essential into 'a must.' In our theory learning, struggling with letter name identities of the pitches is akin to not really knowing the alphabet when learning to read and spelling etc. The transfer rate of info kabooms when letter names are in place. You'll be glad you did when you get a lesson with a pro who is helping you find the 'pitches in between' the ones you already know. Here's a chart to help. Ex 3. |

|

Major key perspective / author's note. Nearly all of what follows is from a major key perspective, in 'G' major. That four songs out of the 50+ that are included in the Omnibook are in a major key is my justification in all of this. Most any other jazz real book follows along similar lines; nine out of 10 songs start and finish in a major key. So if you totally dig Gregorian chants, or are a reggae artist crossing over, this 'major key perspective' might rub a bit, as much of the music of these styles is in minor keys. Sorry. I just have to go along the mainstream in this, for to try and write of both perspectives all through the book I probably might not ever get finished. |

|

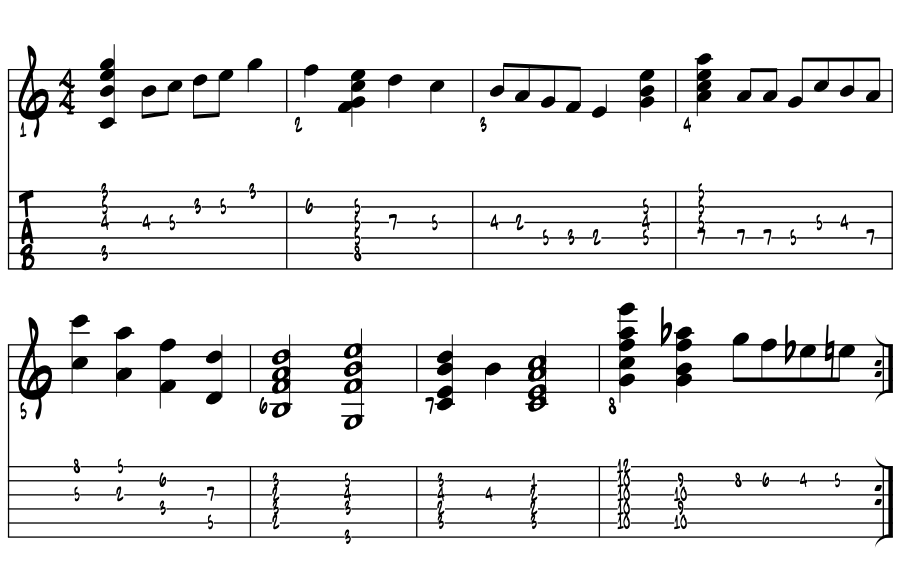

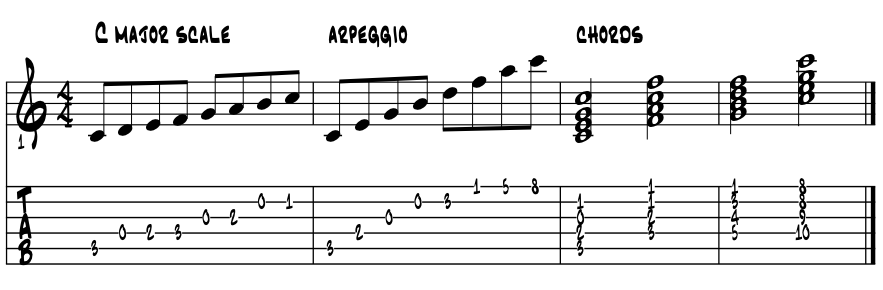

Scales / arpeggio / chords. Every picture tells a story don't it :) This evolution is a well worn pathway to the whole tamale stand. Example 4. |

|

Scales / arpeggio / chords. Cool with what just happened? Need to review this process ? Easy do. |

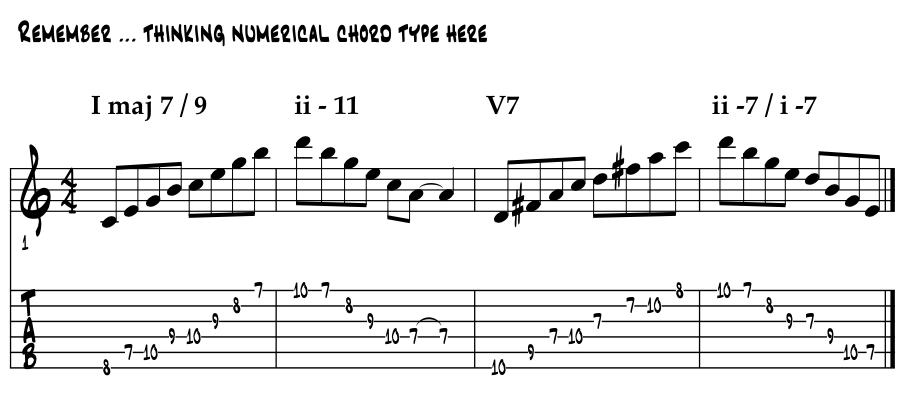

Jazz harmony / chord type. In examining diatonic harmony in general and in these discussions of the jazz stylings, there's two ideas to add into the mix; first is that most jazz chords, like in the blues, will include a 7th above the triad. Two; and perhaps this is the more important idea here; that any chord in our galaxy of harmony belongs to one of three families of what is commonly termed as a 'chord type.' There's three chord types; tonic / One, dominant / Five and supertonic Two, these three families of chords together create the Two / Five / One cadential motion, which in the real basics of jazz chord progressions, is so essential to the performance of many many many jazz standards. Example 5. Chord type simply is defined by chord quality; so what is the chord's triad ? Major or minor ? And what type of 7th is included. That's it. Major or minor triad, major or minor 7th. Easy to rote on up. |

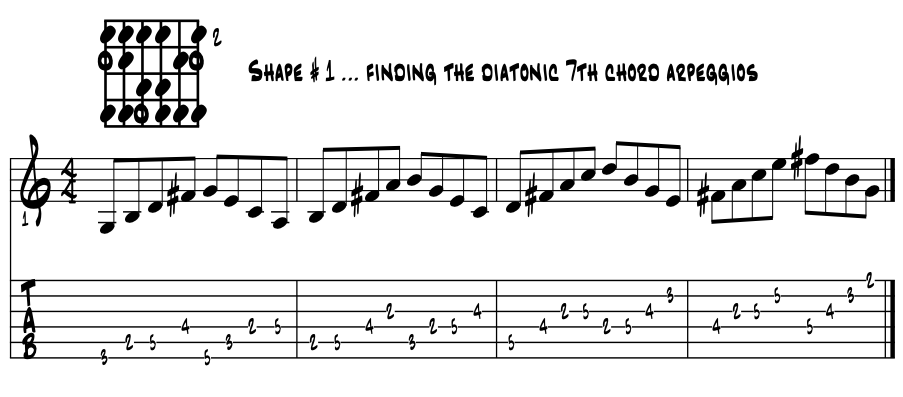

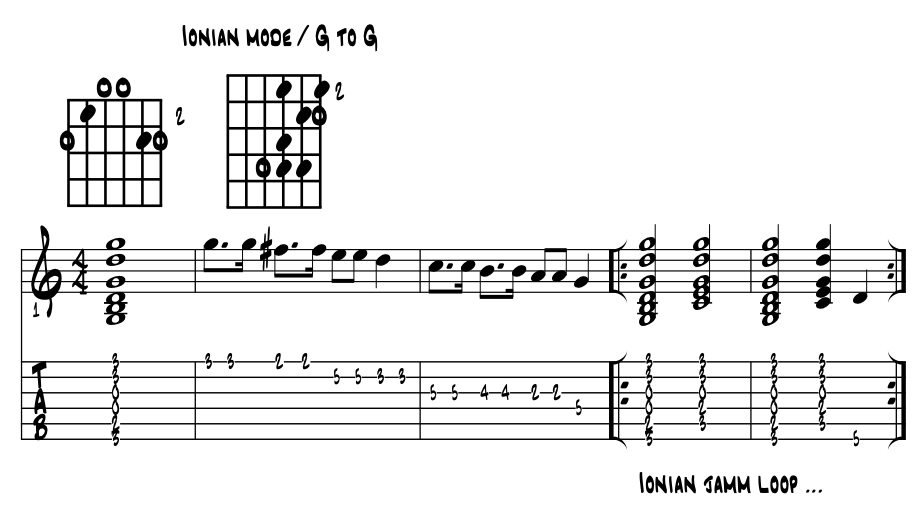

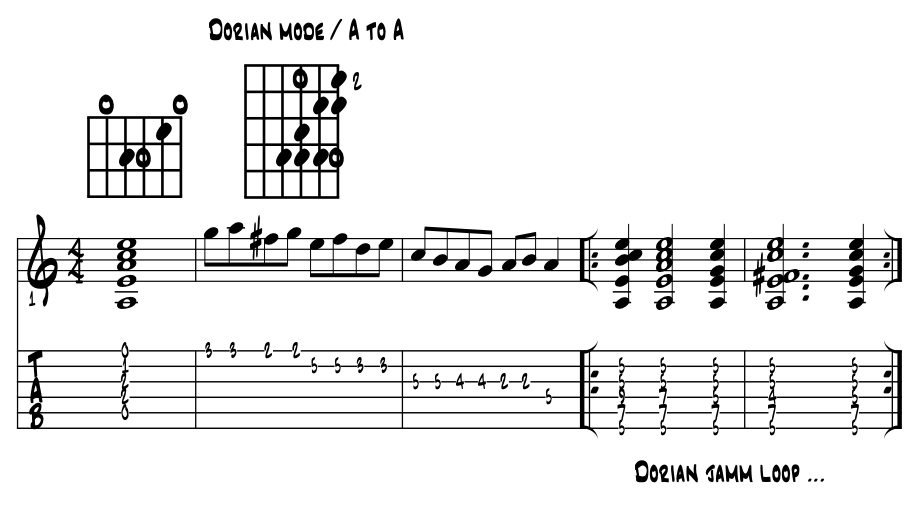

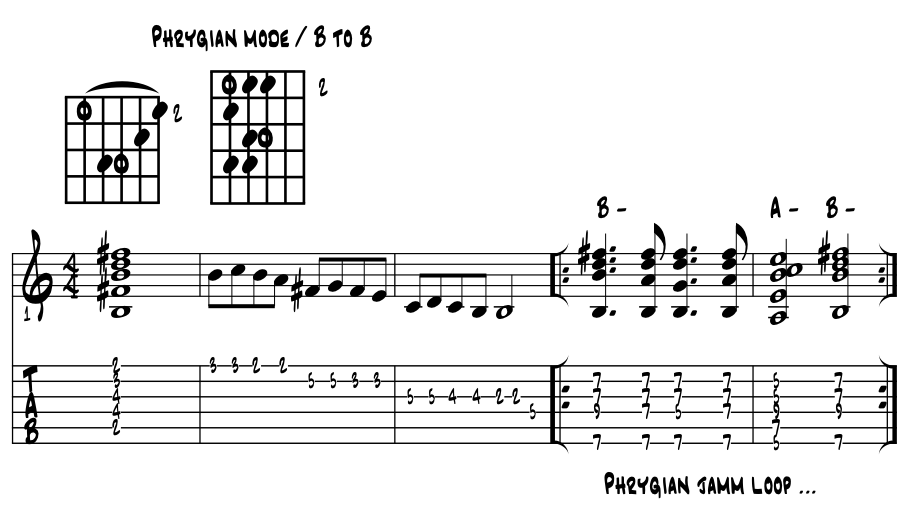

Jazz guitar; five scale shapes / arpeggios / modes. The Essentials jazz guitar method is based on an interlocking pattern of five unique scale shapes. Each of the shapes is a couple of frets wide so all combined we get a fingerboard roadmap for all of our diatonic key centers, the 12 relative major and minors, all their modes, the intervals, arpeggio and chord shapes generated by the pitches in each position. The blues elevator is in these shapes of course, as is the expansion of the first pentatonic box scale to include four more, so 5 total. Surely there can be more, and you will discover your own faves, but these five will feed the jazz bulldog daily. So the five scale shapes which follow should be committed to long term, rote memory with lots of muscle memory thrown in for good measure. For once established, we'll shed into another couple of layers of coolness to these scale shapes to complete this intro to jazz guitar studies and training. |

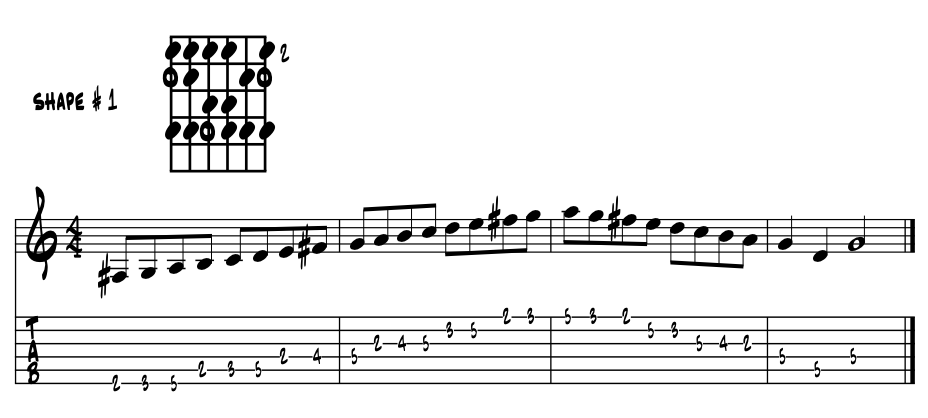

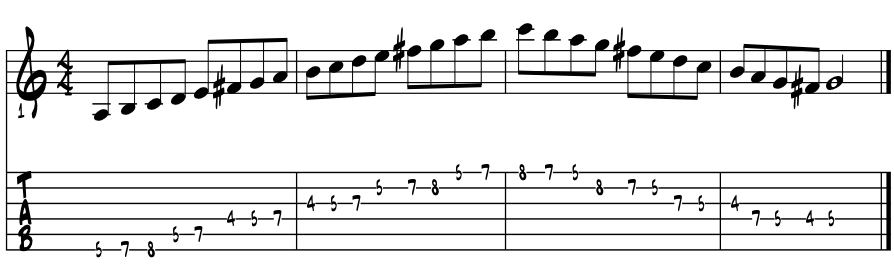

Shape #1 for G major, the 'arpeggio' shape. This first shape is often called the arpeggio shape as it has a nicely symmetrical tonic, major 7th arpeggio right down the middle. Please examine this two octave diatonic major scale shape, get it under your fingers if necessary here and start to run the shape chromatically up and down the neck, keeping track of root pitches / key centers. Starting off on the major seventh pitch of the G major scale and exhausting everything diatonic in the four fret span. Example 6. |

|

Starting off on the leading tone F# and simply finding all of the pitches of G major in this one localized position. The closing Five (D) / One (G) in the written lick is ancient and as solid a way to close a line we get. Here's the major 7th arpeggio shape, a One chord type, from which this shape is named. Example 6a. |

|

Cool huh? Smooth shape for sweep picking? Absolutely. It get's us right up to the Nine colortone in a hurry too ! We'll see this ladder shaped critter again for certain. |

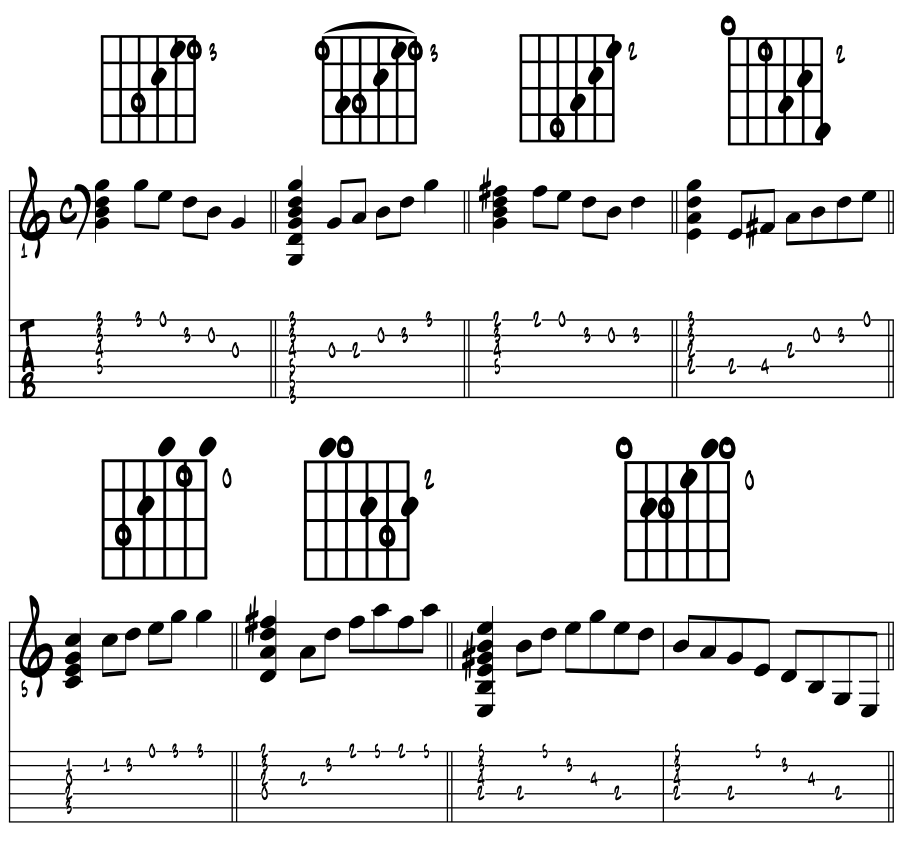

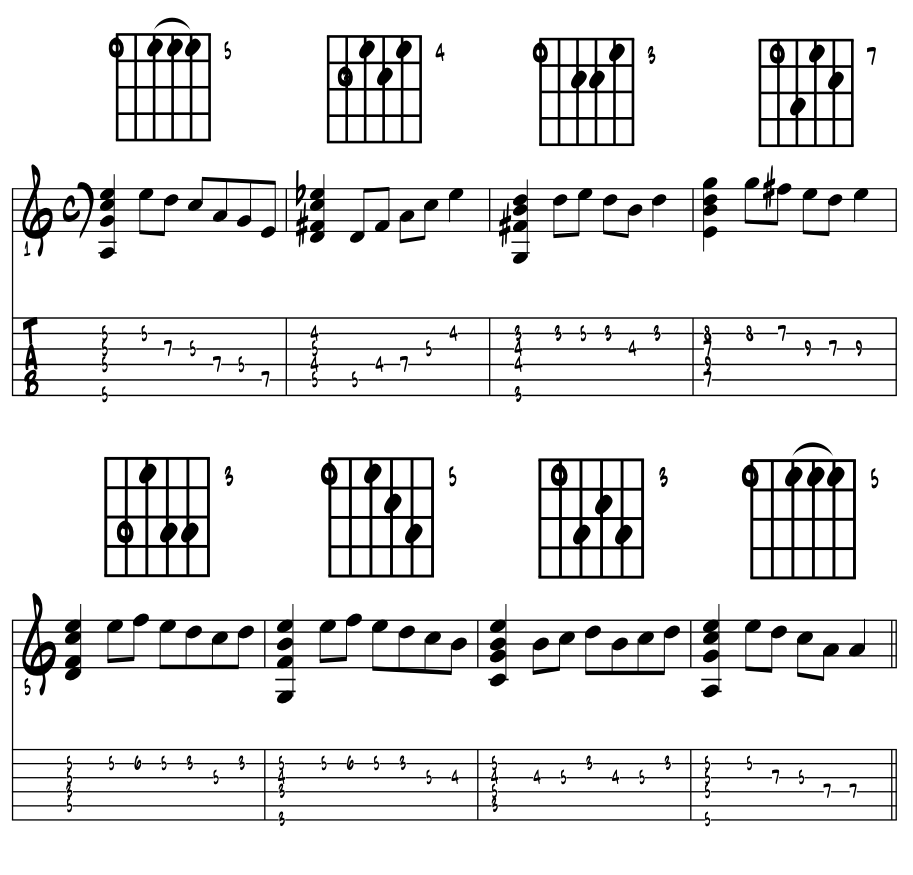

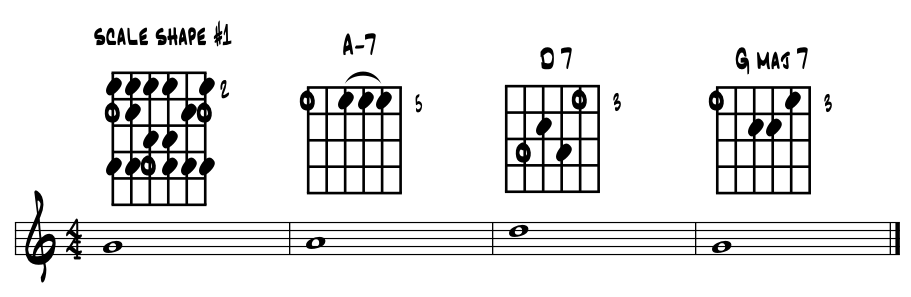

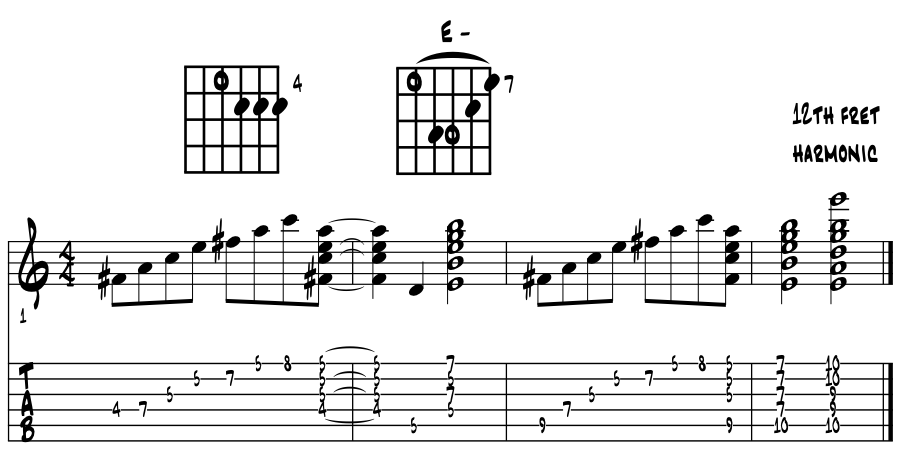

Two / Five One shapes for scale shape # 1. Let's find the movable Two / Five / One chord shapes within scale pattern #1. Example 6b. |

|

Cool harmonies, totally movable, and all three are principle chord types. Call it jazz :) |

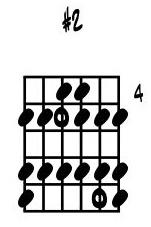

Shape #2 for G major, the 'Two chord' shape. As it's nickname implies, this shape has a ton or two of the blues / jazz world's Two chord Dorian flavor. 'Built right in' to the scale shape as folks used to say. While a fairly friendly scale shape fingering wise, a bit of a shift here or there as your chops desire. Fingerings eventually become more situational to a melody line and surely how fast the music goes along. Faster tempos require more thought to how a slight shift is best achieved. Faster tempos makes easier for booboo's so need more planning. This is especially true of bebop lines. |

Find these pitches with notes and tab, click the music to hear core Dorian's minor modal magic right from the first few notes. Run this shape / pattern up and down the neck to rote learn the shape. Starting off on the major second pitch of the G major scale and exhausting everything diatonic to G major in the five fret span. Example 7.

|

|

Find the G major scale within the shape? Pitch and theory wise probably more A Dorian ... ? Who cares really as we've now got a solid link between shape #1 and #3, there's a super solid G triad right in the middle of this one, with G major still in ascendant :) |

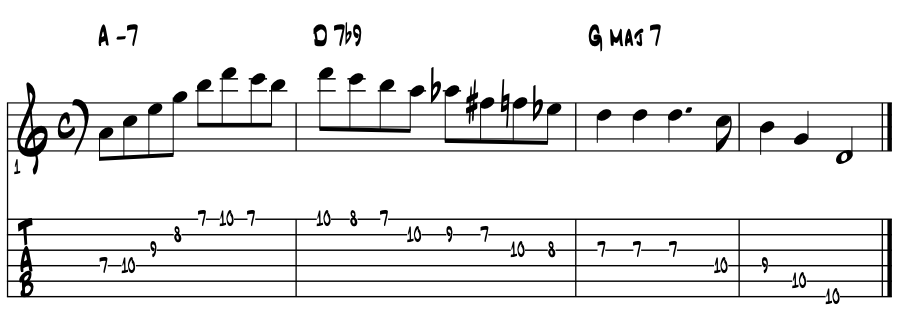

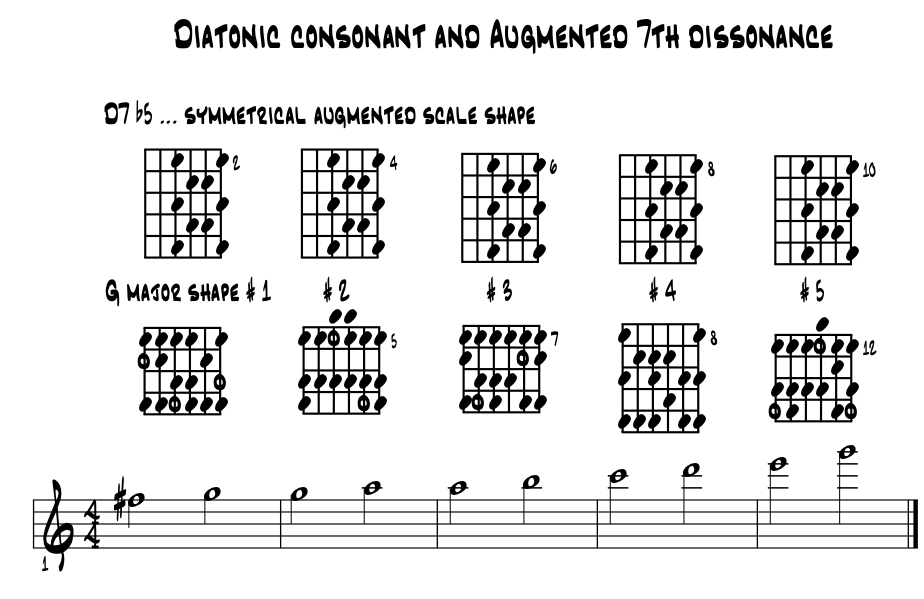

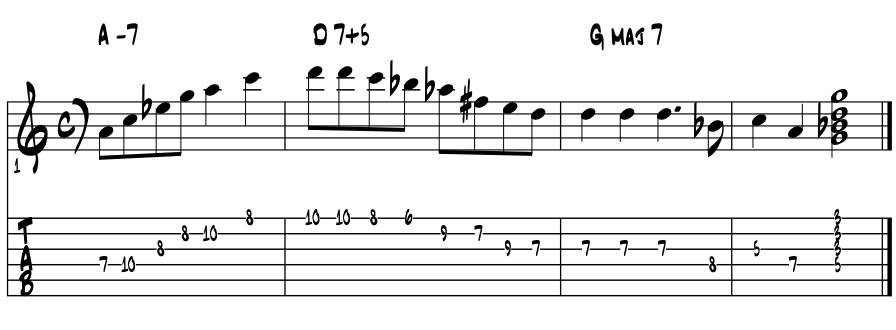

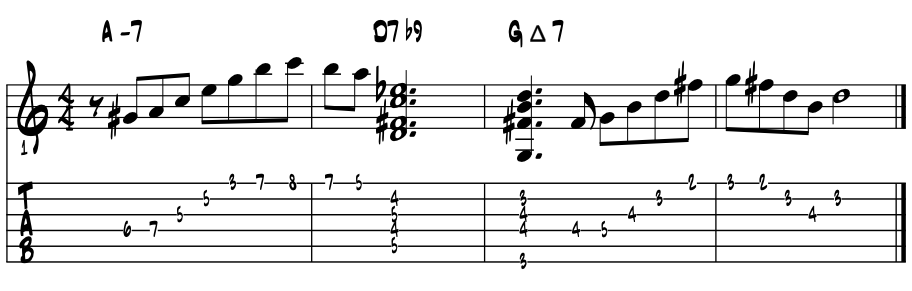

In this next idea we use the easy Two chord DNA of this scale shape to create a jazzy sorts of improv melody line and resolve to G major. So, thinking Two / Five / One in 'G', or A-7 / D7b9 / G major 7 and ending up back around shape #1. Example 7a. |

|

Well kind of got carried away as we ended up back in shape # 1. Oh well that'll happen. Man do those arpeggios ever do tell the harmonic tale. Hip to b9 yet? Oh, and are the chords in the last idea movable shapes too? Indeed they are; root position chords that go to wherever we need them up and down the fingerboard. |

Arpeggios from scale shape # 2. Very similar to the above idea, maybe a bit more academic and closer to what shape # 2 provides. Note Roman numerals. Also, careful as the tab numbers in bars 3 and 4 are goofed up a bit. Find yourself a better fingering. Example 7b. |

|

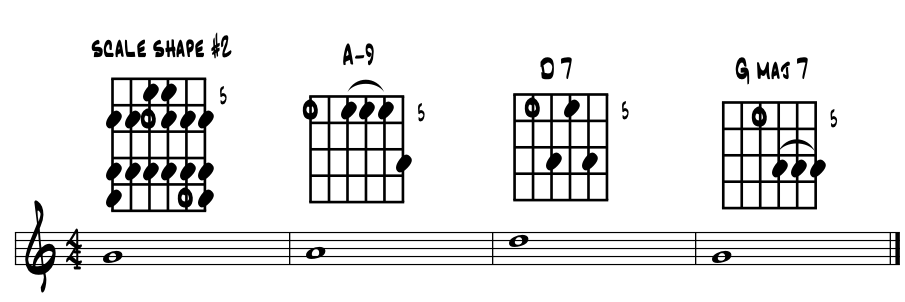

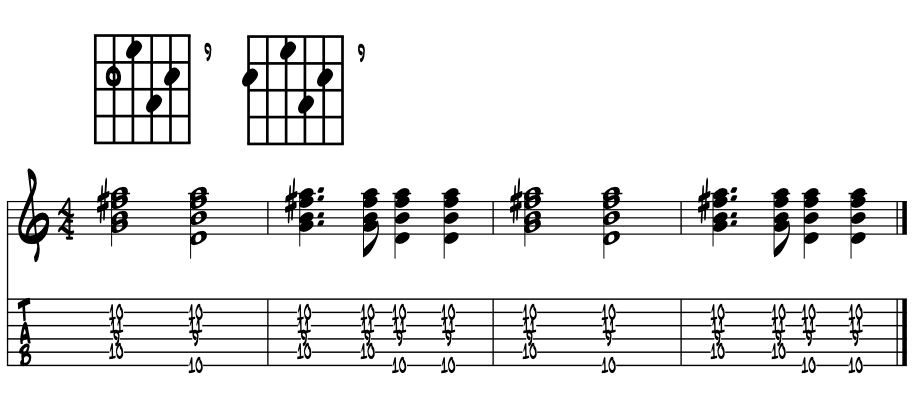

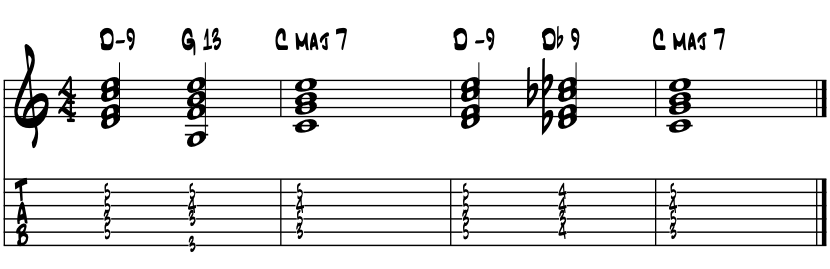

Two / Five One shapes for scale shape # 2. Let's find the movable Two / Five / One chord shapes within scale pattern #2. Adding a 9th to Two, a common enough jazz color, and getting new brand shapes for Five and One. Example 5c. |

|

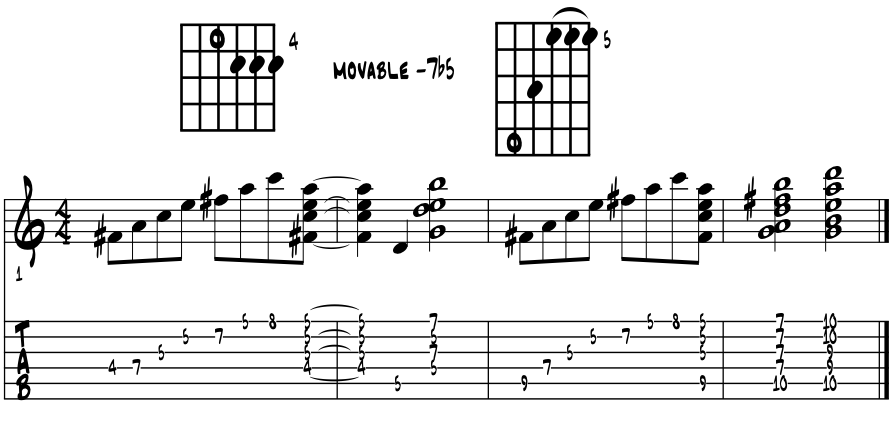

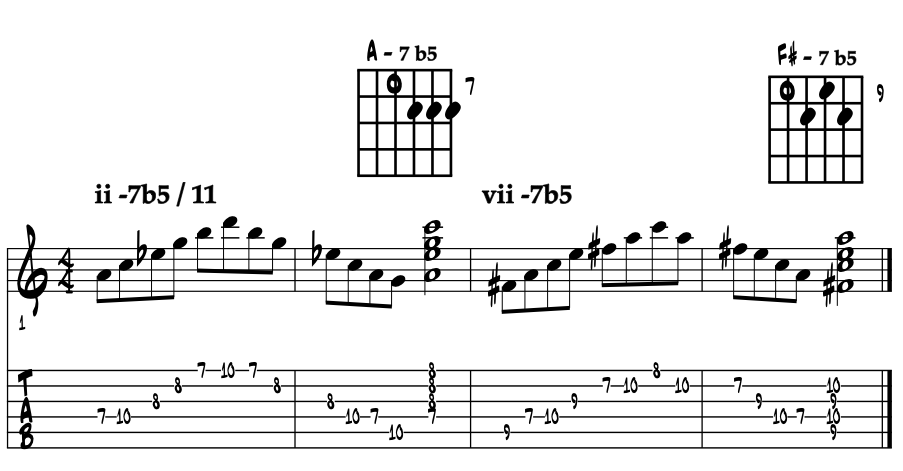

Lest we be remiss ... Sure enough there's a key diatonic half diminished chord here to be discovered, illuminated and linked. Actually two movable shapes, as we'll stretch a bit and move up towards shape # 3 to borrow our root pitch, from the next piece of our fret board puzzle. Building from Seven in 'G' major, a couple of nice, root position movable F# -7b5's keepers, arpeggiated and resolved. Example 5d. |

|

And the balance. Let's resolve these half diminished chords to the relative minor side of 'G major / E minor.' Example 7e. |

|

Diatonic Two in minor. So with all the talk of major this and that, most songs are in major etc., lest we forget that the diminished triad and its extension to 'half diminished 7th', is the diatonic chord built on Two of the natural minor. Well worth exploring for those so inclined as this color finds its way into all sorts of coolness throughout our Americana songbook. |

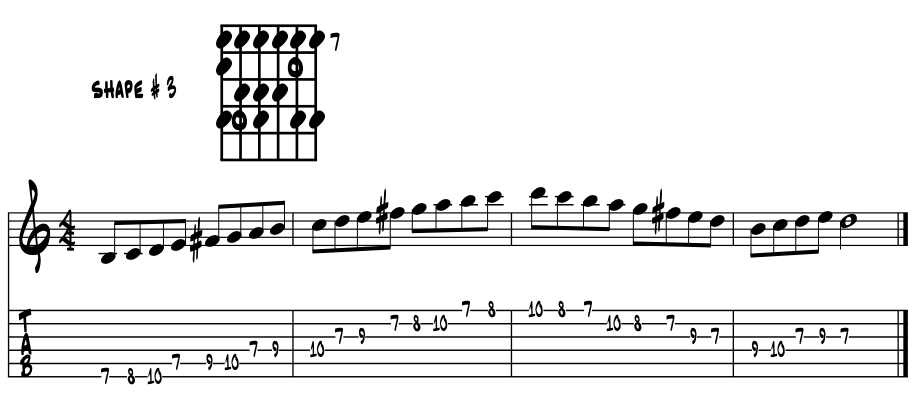

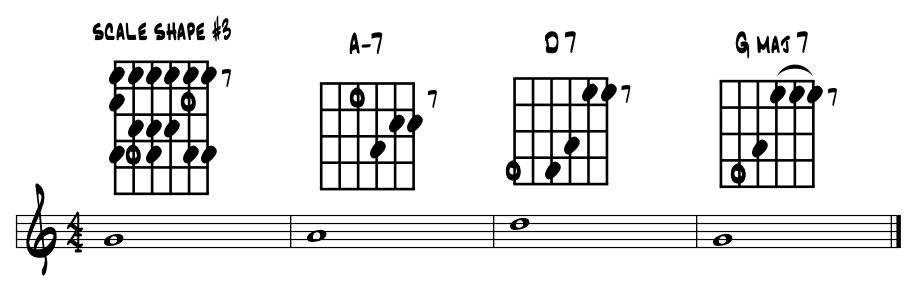

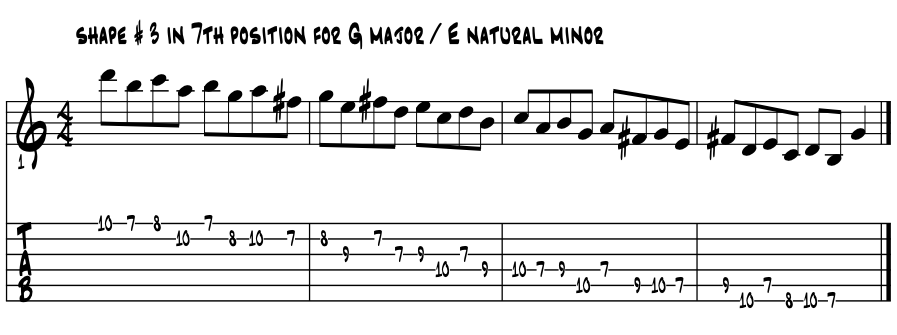

Shape #3, the 'gospel butter' shape. What? Gospel and butter? Yea, just can't decide which description so glue them right together. For this scale shape is as happening as they get. Starting off on the major third pitch of the G major scale and exhausting everything diatonic in its four fret span. Example 8. |

|

Familiar? Cool. See the exact same arpeggio shape as from example 1a from above? Lots and lots of folk / country / bluegrass artists use this one shape down in open position, where its shape sounds out the pitches of C major. Tons of miles in this scale shape for all of our styles really. Even the blues? Yes, but with some blues hue'd variations of course :) |

Regardless, it's a real burner for a lot of cats and super buttery for a lot of Americana melody coolness. In this next idea we simply sequence the pitches of the shape in thirds creating a commonly heard melodic idea throughout the literature. Basic G major scale motion descending in 3rds. Example 6a. |

|

Sound familiar? Really a very common idea through most of our styles. Of course, the thirds are big players in our theory scheming; melodies, arpeggios, chords, major or minor, advanced harmonic cycles. On and on really ... just knowing about them and being curious, we end up bumping into them just about everywhere in our musics. |

Arpeggios from scale shape # 3. By thinking numerical and chord type, these four arpeggios are keepers for sure. The first is a tonic staple, which also shapes the basic launch pad to #15. The minor Two in the second measure is right back to the tonic arpeggio shape first seen back up top. Now starting on the second scale degree. Modal? Yep right up to 11. Measure three has a vanilla V7 shape, but know there's a diminished / b9 scale shape right underneath here in shape # 3. The fourth bar is a straight up minor 7th arpeggio, so either a Two or tonic. Again, all are keepers really. Consider rote memorizing a shape you dig and then running it chromatically up and down the neck to lock it in, keeping track of roots pitches etc. Example 8b. |

|

Of course we forgot at least one arpeggio shape. This 'butter' shape is ... just can't say enough about the magics within. Perhaps the most overlooked of our colors are the diatonic half diminished arpeggios and chords created from Seven of the major scale, and Two of the relative minor. These two 'half diminished' shapes are sure keepers, lots of miles in these for those so directed. Both live snugly within this buttery shape. Example 8c. |

|

Cool sound and a fairly doable fingering yes? There's a side of jazz guitar that's about control of sounding the notes. That every note of a chord voicing gets a finger to sound a pitch, hypothetically anyway. This way, whatever gets sounded is supposed to get sounded :) |

Color tones. When color tones are added to chords and we mix them into other instruments when making the music, we just want to be sure that each pitch we chime in with, is fairly directed and intended. Four finger / four frets, chord voicings such as the above F# -7b5, where each of the four pitches can get a finger to themselves from both hands. That the A-7b5 is the upper part of D9 probably means using a flat fingered approach to the upper three pitches. So 'three for a nickel' from the one butter shape. |

Two / Five / One shapes for scale shape # 3. Let's find the movable Two / Five / One chord shapes within scale pattern #3. Wow, three new shapes. The 'D7 adds 9 and 13, thus qualifies for one of Doc's Hollywood chords. Example 8d. |

|

These shapes are tricky fingerings for sure. But there's a trick to solving the tricky for certain. Get the A-7 shape, strum it once. Move to the D7 shape, strum it once. Find the A- shape, strum it once. Move to D7 etc. Repeat as many times as needed. |

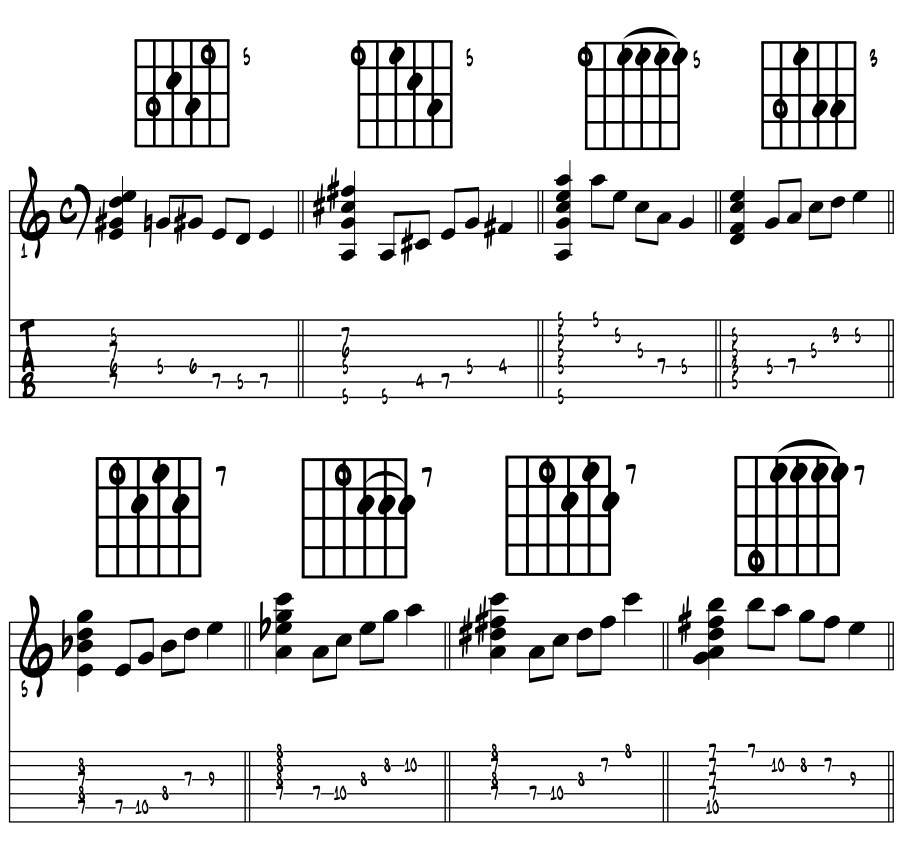

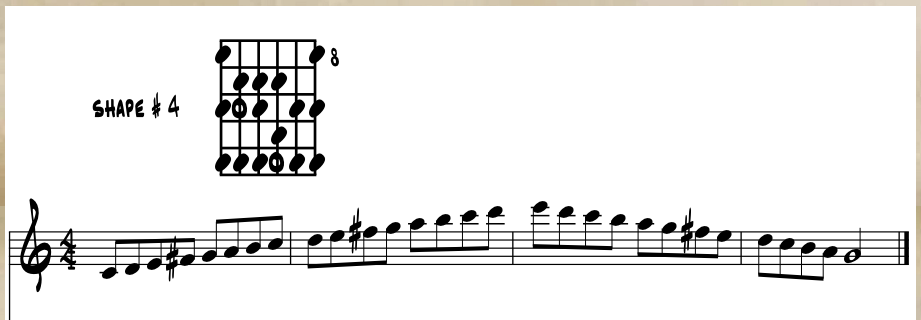

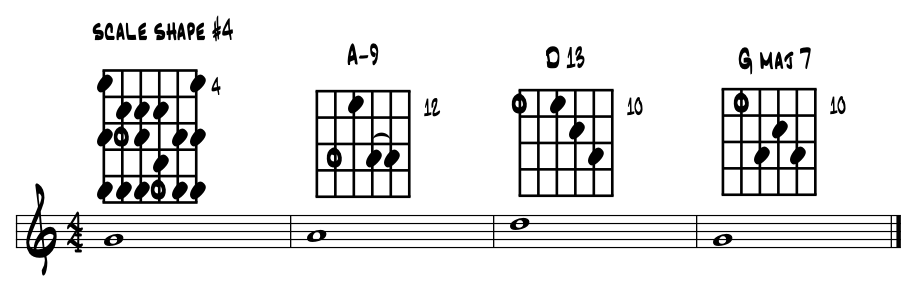

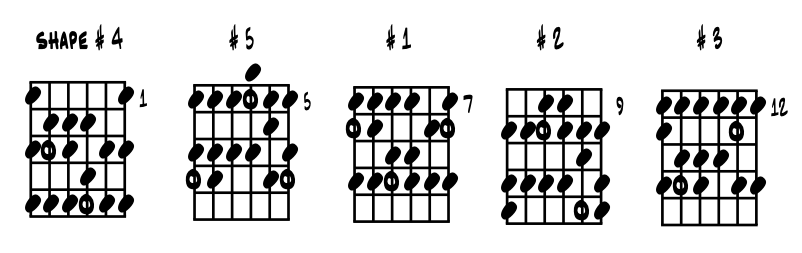

Shape #4 for G major, the 'bossa' shape. As in the Latin bossa nova style? Yep. For there's a 'major 9' chord shape built into this scale shape that owns the warmth of the original core bossa feel. With an alternating bass? Yep, One and Five just a string away. Here's the scale shape first, again G major starting on its 4th pitch 'C', stretching a wee bit to cover all of what is available in this position. Example 9. |

|

|

Tricky fingering? Don't fight it really. How a 'thing' gets played is all about where we find it, how fast, what follows etc. Chances are we won't ever really need the whole shape most of the time. Focus on locating the notes of the group, their letter names. That said, there's a fingering hand solution to this next chord, find the root with your middle finger and the rest should fall right into place. Same finger alternates our bass pitches. Here's the 'major 9' chord voicing that lives in the middle of major scale shape #4 with an alternating One / Five bossa bass motion. Example 9a. |

|

Handy bass motion huh? Yes the alternating bass is a big part of the bossa pocket. So the chord shapes come right out of these five scale shapes? Yep, many do indeed. And if the shapes are movable are the chords all movable too? Pretty much. And if the scale shapes generate the chords then their arpeggios must be in there too? And of course movable? Yep, yep, yep the stars align. The whole tamale on the way to jazz guitardom ? |

|

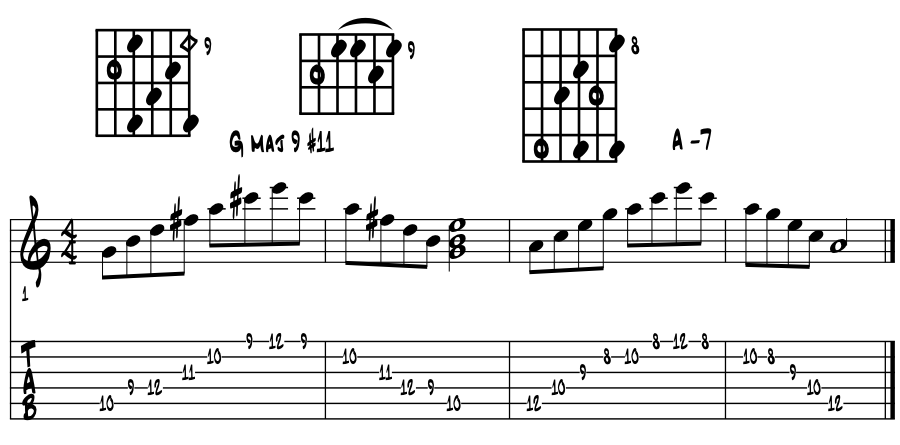

Arpeggio shapes for scale shape # 4. Got two keepers here for sure. The first is a bit of a blast off as we aurally get up to the #11 colortone to sound 'correct.' We'd be remiss not to slip in the tonic / #11 voicing right here too. This is a super keeper for some artists in many jazz ways. First is the commonality of the chord shape itself. If it looks like a barre chord on five strings, right on. No? Quick cruise through the 'evolution of chord shapes' will get you hip right quick. |

Second is the proximity for swapping root notes from the lower root pitches 'G', as notated here, so 'D', right below it. So what is it now? Second inversion G maj 9 #11? Or a D 6/9 maj 7th? An 'A' major triad over 'G?' Or even leave both off and we've a minor 9 / 11 sus chord of sorts from the now lowest pitch 'B' or an 'A' triad over 'B.' Crazy yea but very cool and can be confusing, just more puzzles to sort out as our understanding of the jazz language evolves. |

And the 'A' minor lick? See the outer sort of arc of dots at the top of the shape? Find that 'C' on top at the 8th fret with the index finger, a perfect balance point to smite this one with authority ... meaning fast? Yea, jazz music likes to go fast, thus we jazz guitar players likes to go fasts too :) Example 9b. |

|

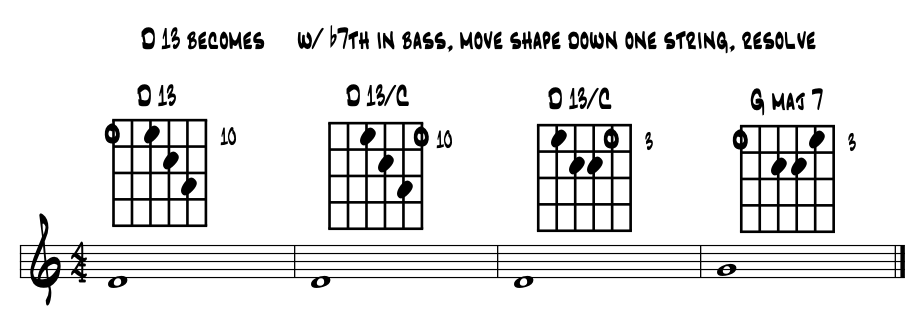

Two / Five One shapes for scale shape # 4. Let's find the movable Two / Five / One chord shapes within scale pattern #4. Wow, three brand new shapes. The 'D' 7 in the middle adds 13 ... thus qualifies for one of Doc's Hollywood chords. Example 9c. |

|

These three jazz chord shapes are among our most common of our Two / Five One progressions. The Two and One chords give us the alternating 'bossa bass' very easily. The Two chord is the shape that covers the basic bass line pattern for "Take Five", an ostinato pattern to motor things along in the A section of its 32 bar form. The D 13 is used in the blues too and without its root pitch (... think from the root), is one V7 chord type shape to be examined for coolness for your work, and if worthy, thoroughly mastered, for it's a three note scooter with a tritone bite. Here's the evolution of the one Five chord shape into three. Example 9d. |

|

|

So from the one voicing we make two more by slight shifts of pitches and moving the pitches down to a lower set of strings. Very common way of finding new coolness. The second and third shapes, especially with a bass player on the gig, are just too handy to not have under the fingers for the evolving modern guitarist. Do learn and master them here if need be. |

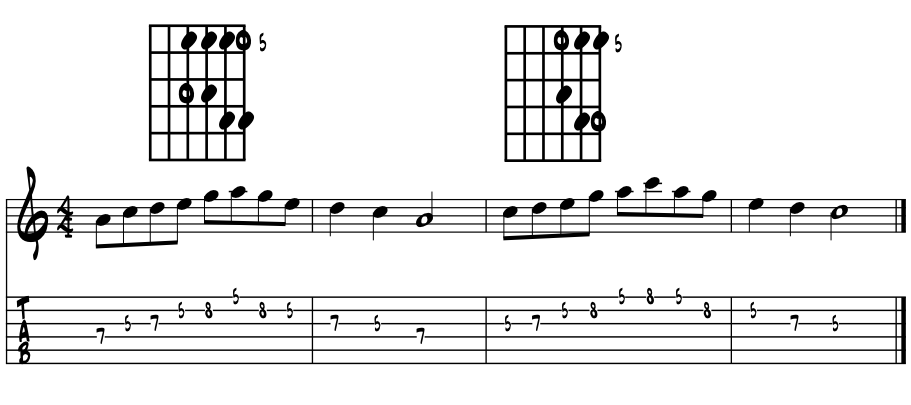

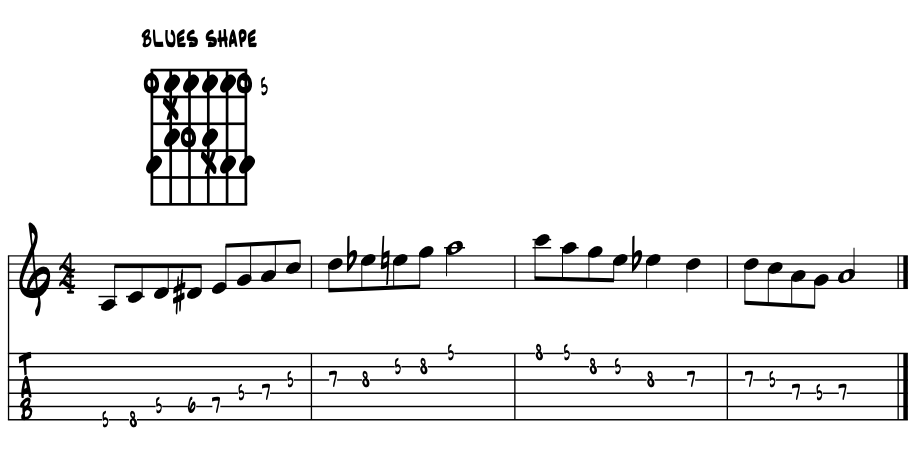

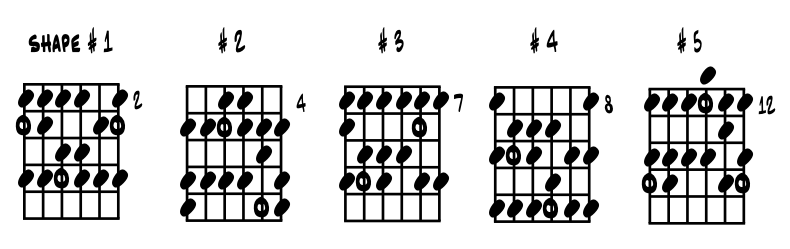

Shape #5 for G major, the 'blues and butter shape.' Saving the best for last? Pretty much depending. For this last idea is oftentimes the first scale shape many of us first learn when starting to make the magic. Two full octaves, and a clear audio of the relative major / minor pairing. Way up on the high notes, some guitars might be out of frets here, proceed with caution :) Example 10. |

|

Cool enough huh ? There's just a ton of melodic fun in this shape. Here's a reduced version, down to just its pentatonic five, in 5th position for easier access. So now, our shapes cover 'C major and A minor.' Example 10a. |

|

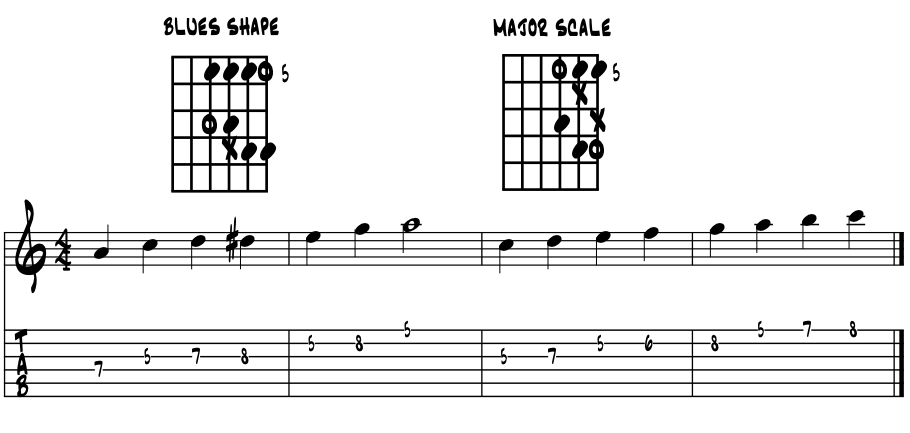

Look familiar? Pretty sure that A minor pattern was the first one I learned. And the C major is the shape used for creating all of the melodies in the 'by ear' songs sections? Tis' is indeed, well after adjustments that is. Such as? Well, to make the 'blues and butter' we need the tritone color too. Add it in shall we? Sure. A one pitch, octave splitting tritone for the blues and a two pitch, tritone interval to make the butter. Example 10b. |

|

So 'X' marks the tritone spots? Surely they do Amigo, for both the blues and major scale colors come right forth when sounded with their five pitch basis. As this theory is also a 'super theory game changer', better split these up for clarity of discussion. Here's the full blues shape. Example 10cc. |

|

|

Look at all the black dots ! Wow, that all got thick in a hurry. So with the blues scale, at least here in Essentials and for emerging artists mostly, this one scale shape is the core of it all. Fully movable, we just move it where we need in terms of keys and chord changes of a song. In the olden days cats called it a 'box' scale. We can initially evolve our blues vocabulary of ideas by finding a lick from the box, then simply relocating that idea to other spots on the neck with the exact same pitches. Rarely will they have all of the black dots as shown above :) |

What we discover oftentimes is that the same idea in different spots evolves; might sound a bit different, higher or lower in pitch, lends itself to other fingerings thus embellishments, surely other string bends and double stops associated with the same pitches. For the cats reading here who have the mojo to take blues licks right off their records, i.e., transcribing, finding the exact spot where they hear the idea is just part of the coolness of their discovery and surely ties into the way the blues has always been passed from one generation to the next. |

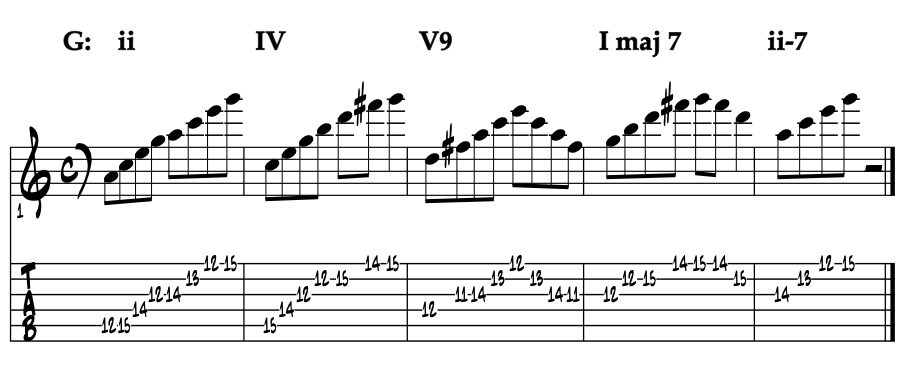

Arpeggios from scale shape # 5. "Somewhere over the rainbow, way up high ...', remember these are all movable so don't struggle with fret location etc. The first 'ii chord' arpeggio is a real keeper, cats blaze this one and find cool ways to resolve the line with a descending lick. The second idea, from 'IV', gets us to #11, so again way up high, and this time to near the top of the color tones ! The 'V9' is a just a bit of thing really, but once mastered is a cool 'cell' that moves chromatically like butter. The tonic arpeggio likewise, short and sweet. The last 'ii-7' a four note blazer arpeggio that tells the tale. Ex. 10d. |

|

Ton a miles on these launch pads, find a fave or two and run them all around the town. |

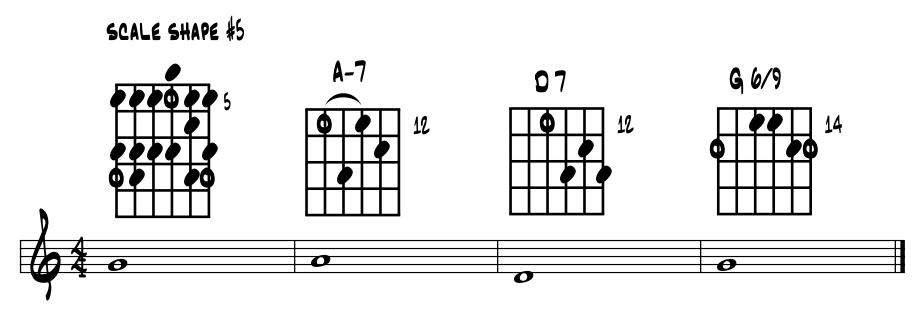

Two / Five / One shapes for scale shape # 5. Let's find the movable Two / Five / One chord shapes within scale pattern #5. Wow, three new shapes again ! The A-7 is the open chord A- up one octave and barred. The D7 is on the vanilla side of things jazz but common in the blues, collapses down in a heartbeat to a fully diminished 7th chord and ... is a nice old gentle sort of V7 with the major 3rd in the lead, works cool on the jazz blues standard "All Blues" by trumpeter Miles Davis. The tonic, G 6/9, while still wholly diatonic, moves us into the quartile possibilities, so creating chords in stacked 4th's as opposed to the 3rd's of tertian harmony. Surely a game changer for cats looking for the next harmonic level in their jazz studies. Example 10e. |

|

Some octave closure here from the A -7 chord; same shape as the open voicing now moved up one full octave. Again, the D7 shape is an old timey blues chord that 'collapses' right into a diminished shape, which we would simply call a common tone diminished, sharing the common root pitch 'D.' While this is an early early blues lick, from the 30's even, jazzers picked up on it and will use this diminished color as a temporary One chord, to mix things up a bit and delay 'a bit further' the impending resolution. Jazz pianist Bill Evans had a knack for this 'extending things along', using altered tonic chords at points in the song normally reserved for clear resolutions, so jazzing it up, while performing in his trio format collaborations. |

|

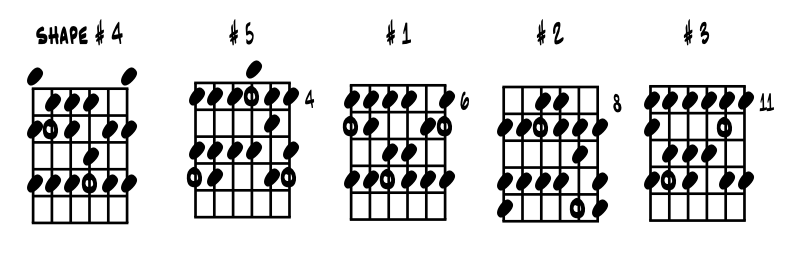

Quick review. Here's a quick and condensed review of the five scale shapes and associated Two / Five / One chords. This one pic might be worth printing and posting for easy reference. Author's note. Once solid with the diatonic running of the pitches, keep a basic shape and chromaticize the location by filling in the spaces in between the black dots. Keep aiming for the open circle pitches as they are the tonic note of its key. Example 8e. |

|

'20 shapes and down the road.' Depending on what music you're working on, performing etc., getting these 20 root position movable shapes (5 x 4 ) fluid should feed the jazz bulldog for the foreseeable future. Throw in 12 keys and our number jumps to 240 for these shapes and chords to play songs in a chosen key center. If you're cool at this level in whatever way, and are needing additional 'ascensions in understanding' for jazz guitar and general jazz studies. |

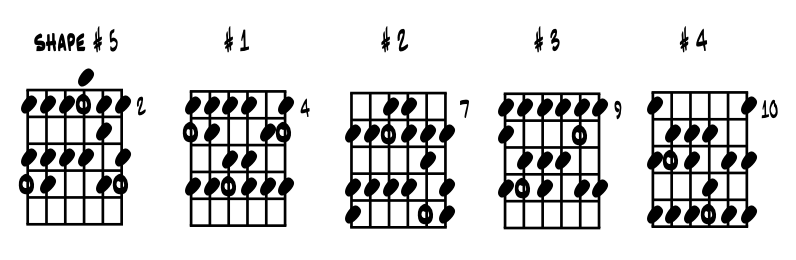

So ... if we had a sixth shape. Well, since we're past the octave 'double dot', it just turns out that we're back to our starting point, but now up one full octave; so our scale shape #1 would be next in our puzzle of these five scale shapes. After one then two, then three to four etc. They're a loop of five shapes that span the guitar's lower octave and puzzle together like this in the relative keys of 'G' major and 'E' natural minor. In this next idea we use the starting bass pitch of each shape to ascend the frets. Example 11. |

|

So for real, this is just one way to conquer this puzzle. There's many many additional approaches to learning the basics of jazz guitar; additional scale shapes, or always having three pitches per string, using wider spans ... and there must be more. And as we'll see in solving the next two puzzles, these five shapes have, and will continue, to feed that jazz bulldog :) |

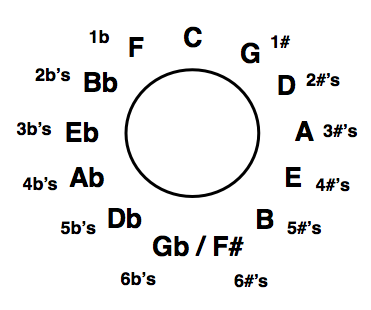

12 paired keys. The presentation of the scales shapes and their number sequence represents the relative key centers of G major and E natural minor, leaving 11 other key centers to be examined. So, can we start at different points in the cycle, following the sequence and find the other keys? Yep, that is exactly how this system works. |

Following the cycle of fifths to organize our keys, the following sequences of scale shapes create the following key centers over the first octave range of our fingerboard. Here presented in a numerical shorthand of sorts, click their link to go to their full presentation as key centers, their pitches, arpeggios and chords and sequencing of the five shapes. Example 11a. |

flats |

|

sharps |

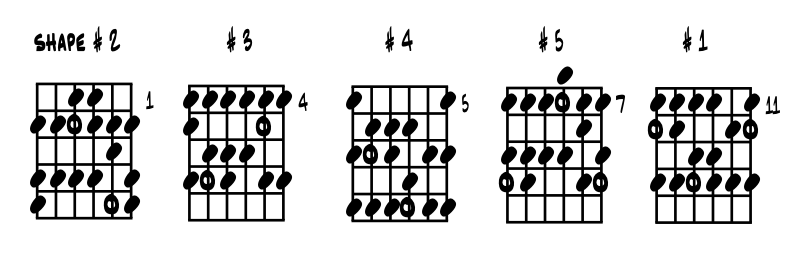

In the following idea we look at the 12 relative key centers and puzzle out the five movable shapes to find their pitches over the first octave of the fingerboard. Open shapes with open strings are omitted here. The open circle notes are the root pitches of the major key associated with each group. Example 11b. |

key center |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E major / C# minor. Open circles are for the pitch E, root of the major scale. Locate your C#'s in these shapes and they will be yours forever. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

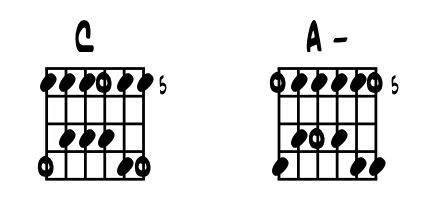

C major / A minor |

|

|

So that's the whole tamale for our ancient diatonic scale, run through equal temper tuning, to create our modern pitch resource for six string jazz guitar. Actually, our guitar's early ancestor the lute, whose fret positioning is measured into place by the mathematics of what is termed 'the rule of 18', had this same 12 key pitch ability. According to a method book credited to the father of famed astronomer Galileo, the lute, of say the 1550's, had equal temper tunings ability; so anything from anywhere? Yep, any lick, ditty, riff scale, arpeggio, chord and beyond equally available from the original 12 pitches, as brought forth by Pythagoras and perfected through the millennia. Nice. |

|

One at a time. Now take each shape individually and run it up and down the neck noting key centers and their pitches etc. Did you get to all the letter names / pitch locations up top? Cool. This 'one at a time up and down the neck' rote learns the shapes. Simply move shape # 1 chromatically up and down the neck. Lock in and muscle memory the shape. This sort of practice / exercise / work is what is commonly termed shedding. |

Follow through with the other 4 shapes. Once the shape # 1 is solid, take each of the remaining four shapes and one by one, run them up and down the fingerboard, noting key centers etc., to rote learn / muscle memory each shape. This basic 'shape shedding' is months of work for most of us. Decades ago I helped a metal artist through this basic shedding. Six weeks later the cat was on to generating the intervals and arpeggios from each pitch in each shape. An amazing talent and intellect. |

Keeping it local. Once the five shapes are locked in a bit, try finding all 12 major keys in a localized position. In this next idea, look to hang right around 5th position; the 5th fret, and get through all 12 key centers. Some shifting and drifting to nearby frets for sure, but just as we say; 'trying to keep it local.' Example 12. |

| Stem to stern. Run this idea stem to stern, up and down the neck, just be creative and find your own ways; 'grist for the mill.' There's surely other solutions to all of this madness, find your own way. Finding some 'go to' spots of pitches you dig? "There's probably some money in those frets for ya." |

Now all on the one string. Ever hear and dig those monster violin masters who play those cool and exhilarating runs up that seeming rather small and fragile neck, yet fill a concert hall with a sound that makes 'ya wanna cry out ... how did you do that ?' Well me too, and then I got to see Pat Metheny a couple of times in concert and thought wow, that's how they do that, how we can do that with Americana jazz guitar :) So in this next idea, we simply play a 'G' major scale from top to bottom on just the one high 'E' string. And as we descend we realize that if we stop anywhere along the way, that thanks to the five shapes, we've a whole mess of pitches in 'G', right there, in that location. And of course 'E' minor too. Plus, all that comes along with the shape; scales, modes, intervals, arpeggios, chords and blue notes. Crazy I know but man does racing up and down on just the one string electrify the joint, trust me, seeing is believing and surely well worth the price of admission :) As is having tab numbers for this next idea, not set in stone, just adjust as ya go along. Example 13. |

|

| Again ... stem to stern. Run this idea stem to stern, up and down the neck, just be creative and find your own ways; 'grist for the mill' yields coolness as the process unfolds. These become 'yours.' And with the looping nature of the five shapes, we get this melodic strategy in all 12 keys too; major / minor, all the modes, intervals, arpeggios and chords. It's jazz guitar, what's not to love ? |

|

Interval studies. This following sequence of learning placing each of the 12 pitches as a functioning key center over the first 12 frets has deep historical roots. We can trace back this Euro methodology to the lute era and forward through classical guitar methodology of the 19th and 20th centuries. When Americana jazz guitar comes along in the 1920's, its blue's origins dovetail right into the classical guitar's 12 pitch abilities, encouraging its eventual evolution into a single line melody and soloing instrument, just like the horns in jazz. |

Our guitars have been built and standard tuned to the paired / relative keys of 'G' major and 'E' minor for the last couple of hundred years. And in locating the other 11 paired keys centers, the 'G / E' pitches pitches become the initial scaffolding up the fretboard to the 12 fret. Once there, all shapes perfectly loop up an octave. |

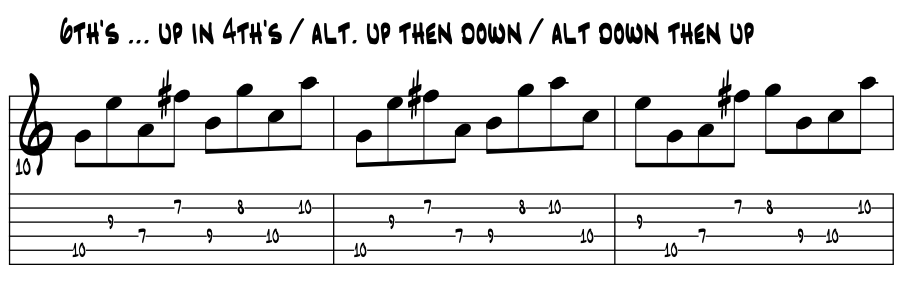

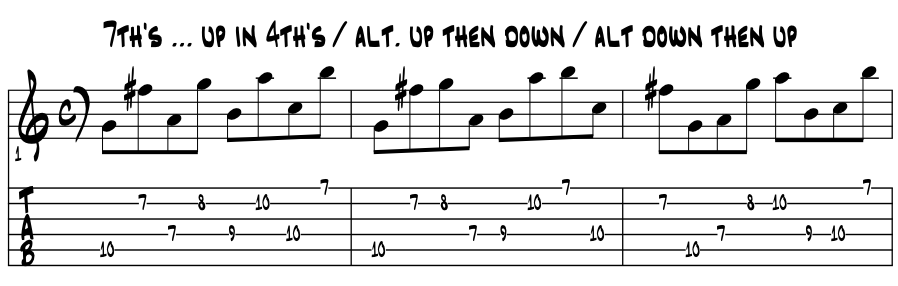

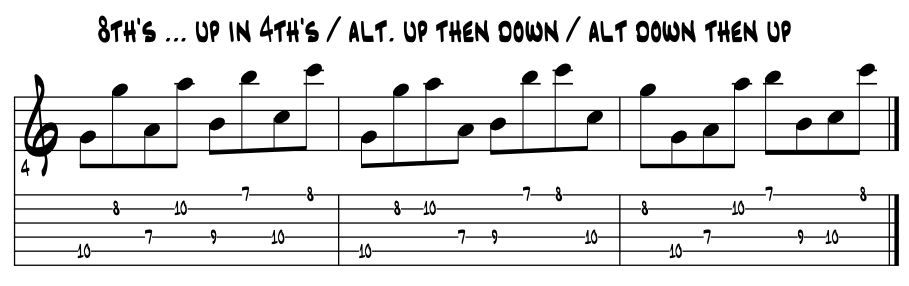

Finding the intervals. With the five basic shapes finding their way under the fingers, and for any melody instrument too, now we begin a new next level for additional studies using the seven intervals we have in the major scale. This shedding will be endless (for some) as it evolves into the idea of permutation; the taking of an idea of a couple of pitches, and generating new coolness into a motif / motive, which can then be sequenced through common filters, further expanding on any melodic idea we dig. Here's an example of an interval study with shape # 3, the 'butter' shape, in diatonic 3rd's, starting off on the dominant note of the key, the 5th scale degree. Example 14. |

|

Cool ? There's a lot going on in this one lick. So getting it up the fingers should open whole new vistas. Or, an easy one for ya ... ? Then run it up and down the neck as an exercise shape, keeping track of key centers. Or maybe get some clicks going and pepper in a few chords along the way, staying mostly in position. Did your shedding / exercises just go kaboom by chance ... ? |

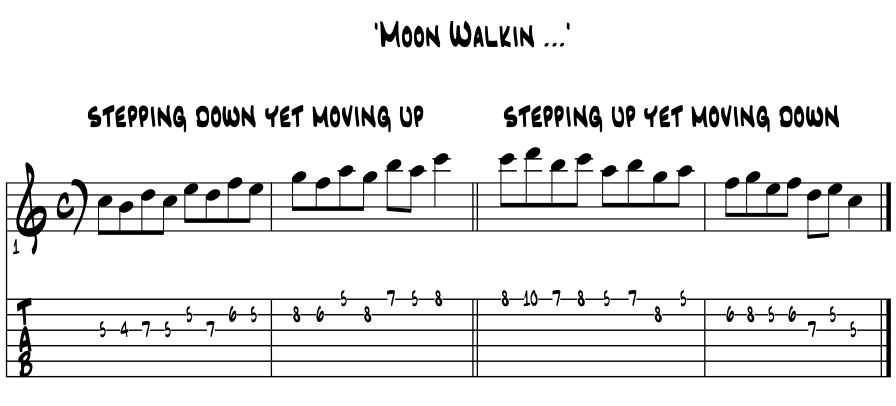

Stepwise motions. There's two classic jazzy stepwise motions that are reverse images of each other. They work nice in all the styles, they're just that classic. Ya probably know them, learn them here if need be. And since they're stepwise, usually manageable yet bring big juice when played with authority. There's just two and they go like this. Thinking in 'C' major. Example 14a. |

|

Huge miles. These two ideas, with diatonic scales, might be a fundamental as fundamental gets, but for creating lines the bring some solid sensibilities easily directed and understood. The 'moonwalk' licks. like the MJ trick :) |

|

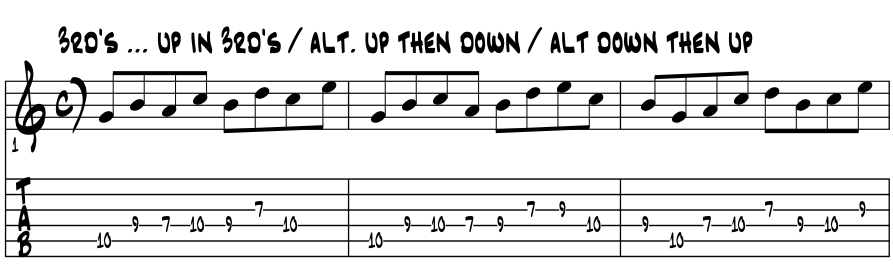

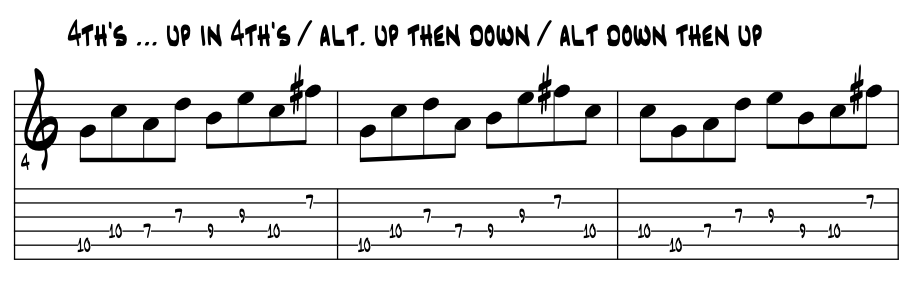

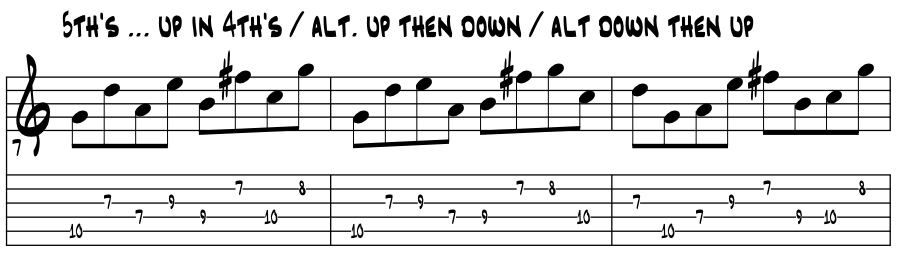

Steps to leaps. Staying in 'G' in 7th position, it goes like this. Once past the stepwise motions, each of the intervals has three initial permutations. In the following examples, they are each one measure in length. 1) motion up in diatonic 3rd's. 2) motion up a 3rd, up by step, then down a 3rd. 3) motion down a 3rd, then by step, then up a 3rd. Once 3rd's are cool, use the same three basic permutations for 4th's, 5th', 6th's, 7th's and octaves. Work these interval permutations through each of the five shapes. There's some 'square pegs / round holes' grist for the mill shedding here for certain, but as we go through the studies, they'll be certain licks of pitches that your ear will just really dig. Extract these, focus in and find what's cool about the permutation. These will help define and add ideas for the development of your own artistic signature. Some just won't take, that's cool, work it at enough to get your chops doing things they might not ever do. Who knows, further on up the road something once discarded may come along again and open a new vista for you to explore. Example 14b. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Making sense ? Cool, yea it's a lot of shedding, rote learning and just plain work. Once you've got it going on, help is there with the clicks, give ya something to lean into, create some swing, even up your 1/8's and take a breath to relax, while time marches on :) |

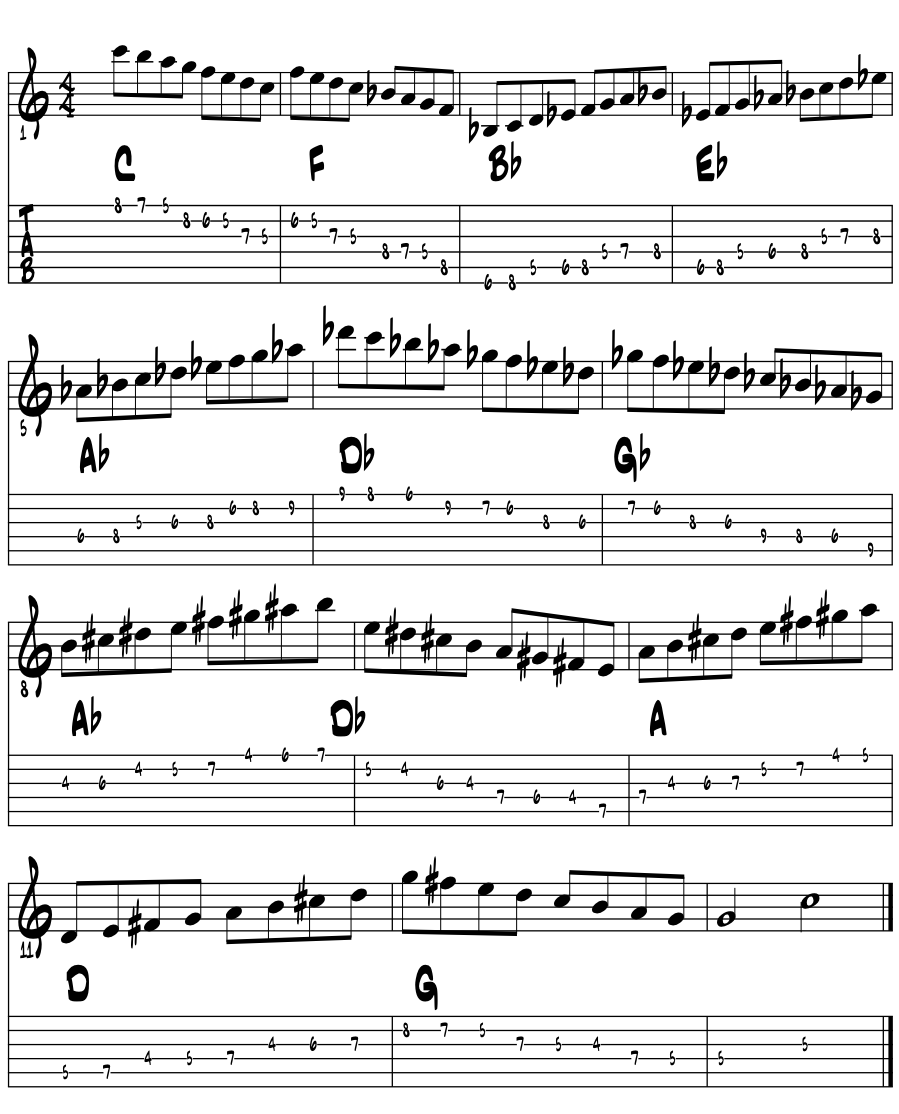

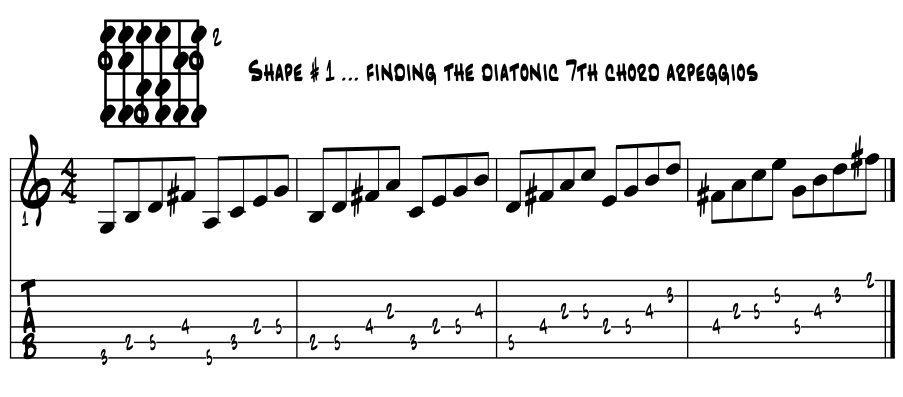

Finding the arpeggios. These exercises follow along with the last entry of shedding the intervals, now we're finding the diatonic 7th chord arpeggio from each pitch of a shape. Motion up for all, then up then down are common permutations. Do make up your own of course. Do work the '7th chord arpeggios' through all five shapes at least a time or two. For some shapes yield blazing arpeggios, some don't ... some fingers are stubby, some slender etc. That down the road as we advance, don't ever be too surprised to find a new gem today that was skipped over back when, overlooked :) Maybe on the first couple of tries, 'there's no money in those frets.' But then on another try on another day in another year, something new is revealed. And maybe that something new becomes a motif for a new song and maybe that new song lights up part of your universe :) Wouldn't be the first time. Here's the basics for shape # 1 in 'G' major. Example 15. |

| There's a flip side to these interval and arpeggio studies; just alternating directions of the pitches. Example 15a. |

|

| Yea pretty academic but a way to strengthen all of the above, especially if you add in some clicks to lean on into, let Franz do the heavy 'time' lifting, that's his bag. Run these last ideas up and down the fingerboard noting key center and pitches. And while all are eventually necessary, we play in some keys more than others, so be sure to master those. |

Through the five shapes. With the five diatonic scale patterns under the fingers, pick out each of the diatonic triads and 7th chord arpeggios found in each pattern. A tall order for certain, just be methodical and create your system for the shedding and understanding of the task. For many of us who have aspired to really play 'bebop' guitar have worked through this prepatory process. |

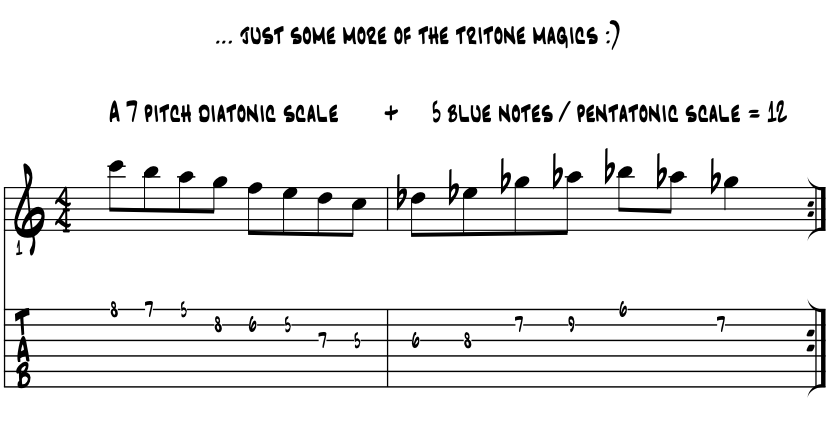

Americana 12 tone. Let's get that old box scale out and find some new, modern sounding coolness from the now ancient shape. For the 'Americana 12 tone' is the 7 pitches of the diatonic scale plus the 5 blue notes, which form up their own pentatonic scale. 7 + 5 = 12 Combining the two ? = chromatic, right. Here in 5th position thinking various things 'C.' Ex. 16. |

So we get 7 diatonic notes in the major scale and the five left over are the blue notes, that also form their own pentatonic scale loop. Root relations? You guessed it; polar opposites on the cycle of 5th's, 'C' and 'Gb', 'just a tritone away from your nearest dissonance.' |

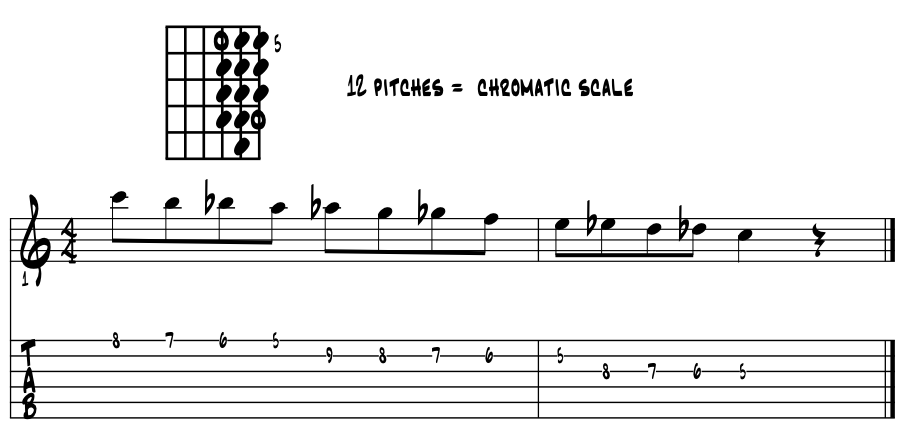

Find the chromatic shape within. Same spot and everything, but now looking for all 12 pitches in and around 5th position. Example 16a. |

A wee bit of magic ... It takes time but eventually the pitches of the jazz language will / could / should / might or not as the case might be ... gradually tend towards the chromatic for the modern guitarist. As we chromaticize our diatonic lines, the degree of the strength of gravity, of tonality and a tonal center, veils or slips away, and we be free'r from the confines of the bar lines and the predictability they often bring. So ... depending on the styles you dig, this may or may not be the direction you be going. You explore and you choose :) |

|

"I don't know if Charlie Parker was the first to use chromatic ideas in his blues lines, but he sure was the King of doing it." |

wiki ~ Herb Ellis |

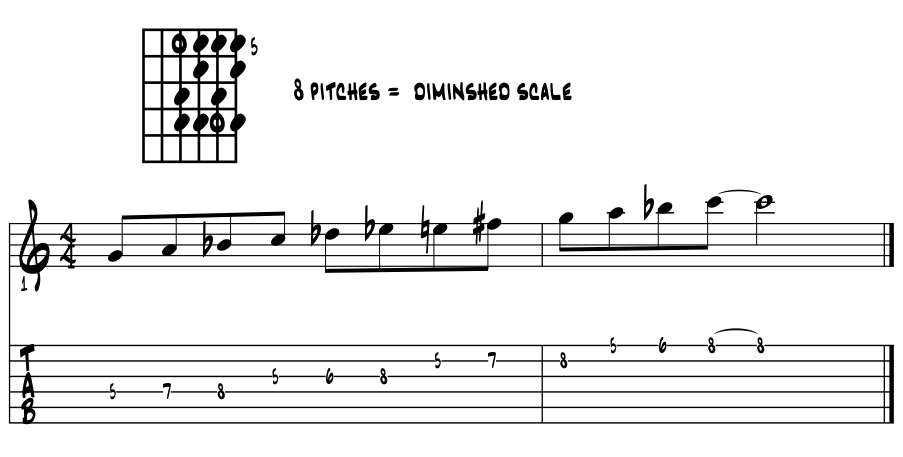

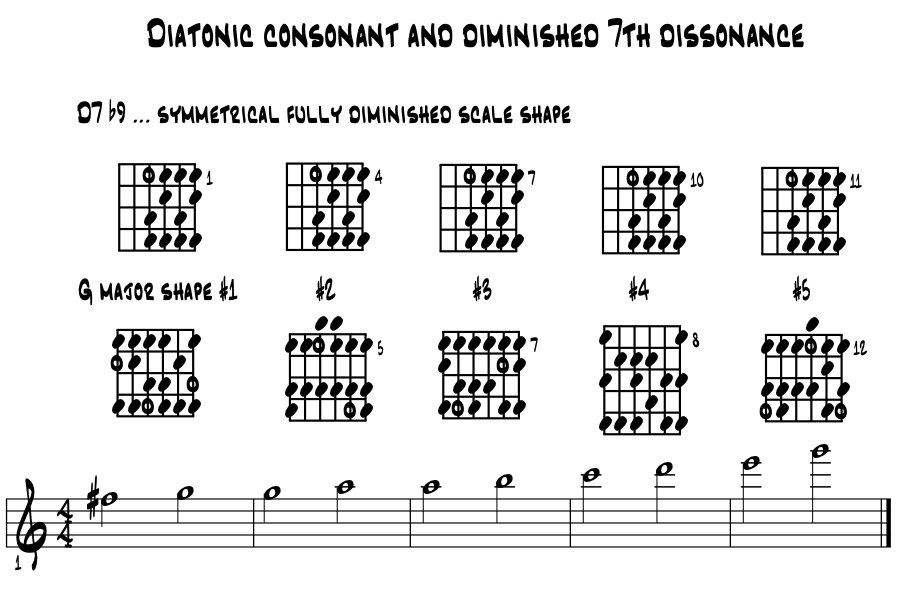

Find the fully diminished shape within. Using the same spot on the neck and everything, but now we're looking for the eight pitches of the diminished scale from the chromatic group above. And while this may look like a 'C' diminished scale, it's not quite the one we want now. Note the 'G' root pitch designated by the open circles. Why this designation is so is a whole 'nother conversation for sure. Here and now, just marvel at the coolness of the symmetrical shape that is a fully movable, fully diminished grouping of pitches. Ex 17b. |

Depending on how you evolve in your musics, this last diminished shape can be a game changer for sure, for a couple of super solid theory reasons. First, that the minor 3rd symmetry of the diminished group will perfectly invert its pitches every three frets. So this shape as written in the last example will have the same pitches when located on the 2nd, 5th, 8th and 11th frets. They just have different starting pitches, 'E', 'G', 'Bb' and 'Db' respectively. Thus empowered, we get a nice potential of mixing this shape within the five shapes of our relative major / minor groups. Simple shapes to create some tension and resolve it. |

Second, that in theory, each diminished scale has four pairs of tritones, while the fully diminished 7th chords will each have two. These tritone pairs create the resolving tension within any V7 chord, or a as a single tritone note, is the #4 / b5 blue note. So with the tritone substitution, we can flip a tritone and get a new V7 chord of a different root pitch, thus a diatonic resolution to a new key center. Or stay in our key and get a sleeker cadential motion. In jazz, sleeker is faster, and faster is exciting, and exciting is an organic nature of the music. So with a diminished chord, two tritones in the one group, we've four possible resolutions, eight if we're thinking of the combined relative major and minor key center resolutions. For now, super rote the shape to blazing levels. And of course, apply some interval and arpeggio permutations too as you see fit. |

All of this 'myriad of tritone tensions' becomes the theory basis of chord substitution. For here and now, just rote up the shape and such if it is new to you, for it is mostly for jazz performance on guitar, chances are we'll not find it in any prominent way in any of our other Americana styles of music. |

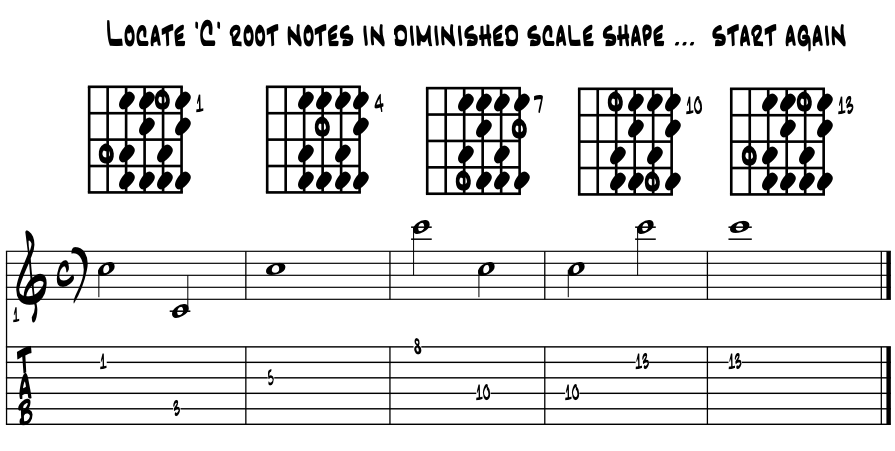

Finding the root notes within the diminished shape. Turns out that with 12 equal pitches and the diminished symmetry of minor 3rd intervals, three' a charm with our diminished 7th arpeggios and chords. Please examine the following pitches as we build the 'dim 7' arpeggio from successive root pitches. Example 17c. C diminished 7th = C Eb Gb A C# diminished 7th = C# E G Bb D diminished 7th = D F Ab B Eb diminished 7th = Eb Gb A C E diminished 7th = E G Bb C# F# diminished 7th = F# A C Eb G diminished 7th = G Bb Db E G# diminished 7th = G# B D F A diminished 7th = A C Eb Gb Bb diminished 7th = Bb Db E G B diminished 7th = B D F Ab B diminished 7th = B D F Ab ... and back to 'C', our start point. Get knocked about by the enharmonic spellings ? No surprise, most of us do. For these four note diminished 'cells' are right frisky critters, chock full of juice to move the music along. Each designated group of three has identical pitches. And trying to sort this on the six strings is a challenge for sure. In reducing our diminished scale shape to four strings / four frets, and knowing there's just the three unique diminished arpeggios; C Eb G A Db E G Bb D F Ab C C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B C ... The combined pitches of the three arpeggios give us the 12 pitches of the chromatic group. Thus empowered, a jazz guitar learning trick is to super rote locate where the root pitches are in relation to the fingering. Starting with 'C', here's how it falls within the minor 3rd, symmetrical diminished shape over the range of the fingerboard; by including all of our 'C' notes on the top four strings. Example 17d. |

We start with the most common of the spots where we find the diminished chords, both written in and subbed into a jazz song's chord progression. And then just branch it out from there. This might be cheatin' but a lot has aligned over the centuries to bring us this color and its multiple resolving properties, in such a handy package. And this is an easy way to blaze it. And this one shape we'll knit into the five relative major / minor scale shapes further on up the road. Academia in part, teaches music by thinking of root pitch to root pitch, of whatever music is being created. We hear this in the blues, the tonic notes of the three principle chords often rings clarion true as the story unfolds through its 12 bar format. It's in all the styles and genres and in truth, "if we think from the root we might never get lost." 'Cause sometimes things are just flying by and ya decide to grab some diminished spice for the gumbo. We can shed the shape pattern and eventually blaze it, what with its four finger / four fret perfection. We can think from the root and blaze away :) Got the letter names of the pitches solid under your fingers ? Cool :) |

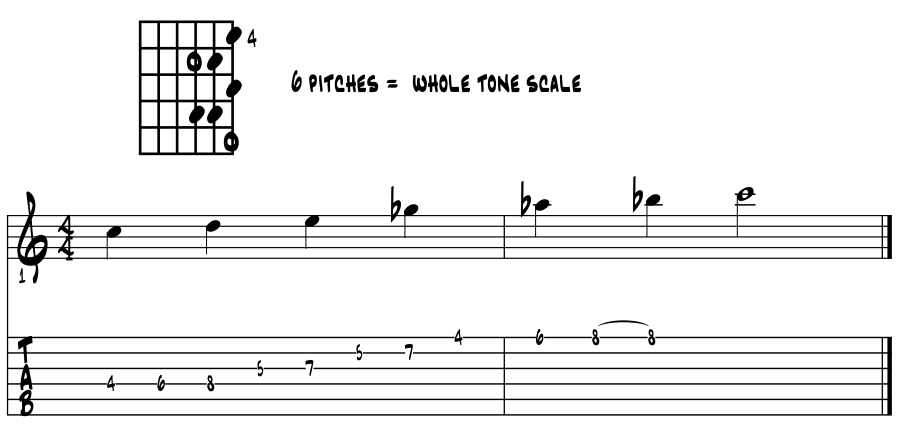

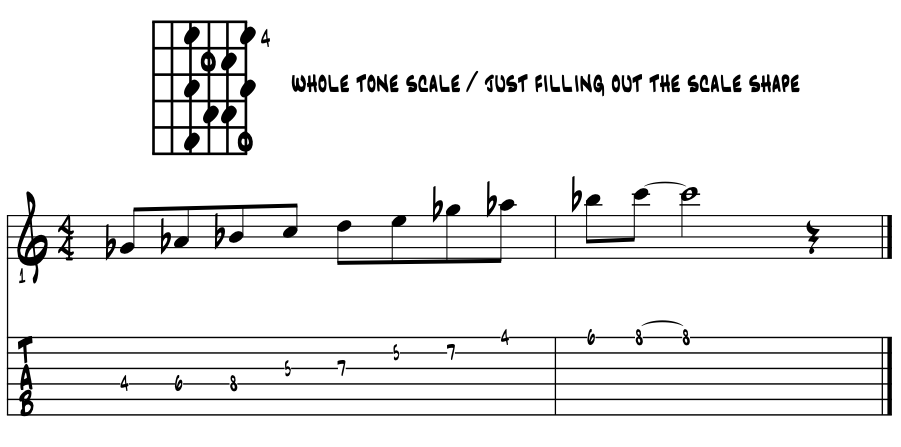

Find the whole tone shape within. Same spot and everything, looking for the 'C' note in the middle, but now looking to extract the six pitches of the whole tone scale from the chromatic group of pitches, all from the same locale on our fingerboard; 5th position. Ex. 18. |

Filling out the shape. Same locale on our fingerboard just filling out the shape to include more localized pitches. Example 18a. |

This shape, and various pieces we can discover within, are all fully movable. All of the pitches are a whole step apart, thus every two frets becomes a possible location and starting point for motion in creating our ideas. |

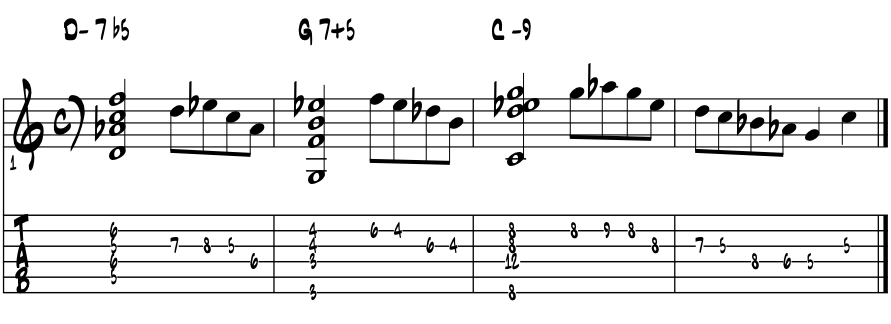

Whole tone magics. Since the construction of this group is all whole steps or whole tones, any one of the pitches can become the tonic or central pitch of the group. So ... six possible resolutions? Yea, six major and minor key centers. The whole tone colors and the augmented triad are part of an evolution of our jazz musics in the late 50's that seems to have come after the explorations of the diminished colors, and their dominant chord evolutions and substitutions based on the V7b9. |

Whole tone loves minor. If there are musical matches made in heaven, this is surely one. Whole tone loves creating a bit of the 'sus float' in the stories of songs that tell us a somber tale. Sharing the minor blue third, between Five and One, here's some of the colors in Two / Five / One action in 'C' minor. Example 18b. |

Cool ? And yea, the minor colors tend to slow things down, give us a chance to dig a little deeper on every pitch. The blue 3rd in whole tone is the 'definer' for all things minor tonality. Half of the Yin / Yang pairing so essential to our lifetime sentient developments:) |

So all of the above are 'movable' forms yes? Absolutely. Everyone of the scale, arpeggio, chord shapes in the above method are all movable, and to think of it, in root position :) So yea, and times it all by 12 and do the math of the way jazz guitar just kabooms equal temper pitches. Plus, since guitar is finger on metal and wood, there's a wide potential for the wiggle in the middle when sounding pitches, and to bring a deeper sense of the blue hue when the spirit moves us. So the best of both tuning worlds and the instruments the build for creating the Americana spectrum of musical styles. A trick link. A link at the top of the page down to near the bottom? Yep, it's a trick so please scroll on back to the top now, and along the way do a first look survey of this jazz guitar method. For the rest of the ideas that follow below are more 'treatments' of the jazz language, the components of which are above. Historically, we as jazz players have just about a century of coolness now to discover and build with, and build upon by adding in our own unique magic of working the pitches, and bring folks together to share in a vision of empathetic togetherness through jazzy musics. Here are topic / links to additional ideas and discussions for jazz guitar studies. |

Finding the 'in ~ out' V7b9 bookends. In this next idea, we use the symmetrical diminished scale shape, created by whole step / half step, which recreates itself as if by magic every three frets. In this shedding routine, we pair it up with each of the five scale shapes for relative major / minor / modes / intervals / triads and arpeggios over the first octave or so of the fingerboard. This diminished group is a 'parent scale' for the fully diminished 7th chord that lives within any V7b9.Thinking in 'G major here and D7b9', our root pitch is 'D', the fully diminished 7th chord is built from the 3rd of the chord, so 'F#'; spelled 'F# A C Eb.' Within this diminished scale are various tensions that we can resolve by slipping back into the relative major / minor scale pitches, from each of its five shapes. Please examine the pitches thinking 'D7b9' into 'G major.' Example 19. |

V7 b9 |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

Eb |

full dim 7 chord

|

|||

diminished 7th scale |

Eb |

F |

Gb (F#) |

Ab |

A |

B |

C |

D |

Eb |

D 7 b9 |

b9 |

b3 |

maj 3 |

b5 |

5 |

6/13 |

b7 |

root |

. |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

. |

|

So each step along the way, up and down the fingerboard, we've this one movable, symmetrical diminished shape that brings quite a bit of dissonant, bluesy and jazzy colors, handily resolved anywhere along the way to our chosen key center pitches. There's a lot of exploring here, and what commonly happens is you will find your own faves along the way. There's a 'something' in each of the five shapes that's cool. Many times, as in the following idea, the pitches of the Two chord are arpeggiated. One super handy combo mixes the diminished color with the 'butter / gospel shape. So in 'G', we're in seventh position, so at the 7th fret. Example 19a. |

Cool ? Yea when things are symmetrical we each often find our own to master the shape, then it'll move faster, faster is sleeker and so forth. The shape also breaks into bits a bit, there's arpeggios within, easy to locate the color tones we want, especially the 'b9', which is what got us here in the first place :) V7b9 leans jazz, seems to be a tricky color anywhere else. |

Finding the 'in out' V7 'b5 / +5' bookends. Here we follow the same format as just above, now with the whole tone color with its similar symmetrical pattern. This shape moves along every whole step, or two, four or six frets, and beyond ! :) Example 19a. |

|

V7 +5 |

D |

F# |

A# |

C |

augmented 7th chord

|

||||

augmented scale |

D |

E |

F# |

G# |

A# |

C |

D |

E |

. |

D 7 b9 |

root |

maj 3 |

maj 3 |

aug 4 |

aug 5 |

b7 |

oct |

. |

. |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

. |

|

As above, so below ... each step along the way, up and down the fingerboard, we've this one movable, symmetrical augmented shape that brings quite a bit of dissonant, bluesy and jazzy colors, handily resolved anywhere along the way to our key center pitches. Again, there's a lot of exploring here, years even. What commonly happens is you will find one idea that really work for ya and rings true, then just build from there. The symmetry of the shape generates ideas by itself. Knowing the theory, players take 'chances' along the way, bring some unpredictability and excitement of the unknown to the moment. U'll find it, just keep playing a bit all along the way. Or a lot, if the jazz bug bites :) Mostly the same like except for the V7 +5 color in the middle of it; tension then more tension then release. Example 19a. |

Surprise ! Cool with minor yes ? In the blues, it's often associated with a minor tonic, as the '+5 of V7' is the blue 3rd of One. |

Soloing through chord changes. 'Hearing the chord changes in the line has historically been the basis of jazz improvisation.' In academia, this is one of the basic skills taught to up and coming players. A fairly sizeable chunk of jazz guitar is the mastery of 'running the changes' in our single note improv melodies. This is a lifetime of coolness for those so disposed, for then search is on for a new line of color to express the essence of our ideas. Empowered with the melodic resources described above, simply find songs with chord progressions you dig and create melody lines that use the pitches of the chords. These we often call a chord's 'parent scale.' Linear, scale shaped lines work this magic also, while properly sounded arpeggios of the written changes always tells the tale. Can you hear the chord changes in the following melody lines? Ex. 19. |

Hearing a One / Six / Two / Five chord progression? Cool. Here's another that uses the five notes of the major pentatonic color to outline the chords of the song, a song that shook the jazz music world 50 years ago that still wakes knowledgeable listening folks right up :) Ex. 19a. |

"Giant Steps" styled melody / changes? Yep, the distinctive minor 3rd / perfect 4th cycling of chords. |

|

Soloing through ... spelling the chords. For those just beginning this 'through the changes' improv, spelling out the chords in our lines, creating arpeggios, is an initial way forward, providing a basis of success that our own ear learns to correct. Learn to spell out the letter names of the pitches that create the chords in your music, and find them on your ax. It's really too easy a process to learn and master to not know of. Here's a chord spelling chart for rote learning. Example 20. |

|

| Diatonic 7th chord spelling chart in 'C' major. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

7th chord quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic triads |

CEG |

DFA |

EGB |

FAC |

GBD |

ACE |

BDF |

CEG |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

analysis numbers |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

2 octave scale |

C D E F G A B C D E F G A B C |

|||||||

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 1 5 |

C . E . G . B . D . F . A . C |

|||||||

Inside / outside the diatonic realm. In jazz music there's another world of musics that live outside of the 'inside playing through changes just discussed. Termed free jazz mostly, we don't very often get to hear it. Generally it is not a big seller, so often tough to get folks to show up. As musicians, we often dig this free environment, which demands that we listen closely and respond in musical kind, to what players are doing around us, most of which does not follow along a form or structure beyond the steady time / groove chosen and the ancient strength of a four bar phrase. |

|

We just need some 'musical time' to get this happening, maybe a bass motif or not, a melody or not, theme and variations or not, call and response or not, advanced cats with a lot to say just chime in and let it flow, creating phrases built one upon another (common in all styles really). so very liberating really. |

So not all of jazz guitar is 'through the changes' sorts of improvisation. Modern players often dig a less structured environment to hang and create in, listen and respond. Not for the faint hearted really, ya need some gusto to make it all go. Of course we can combine the best of both, through the changes or free / over the changes approach, in traditional performance formats. Cats call this inside / outside, a proper (?) mix of which in improvised music is a true wonder to behold. We each get to decide, but improvising even 1/8's lines through changes is today, can be the basis of it all. |

Jazz performance format. The basic way of performing jazz songs usually works as follows; once a song is chosen, the band plays the melody completely through. Sometimes twice if it is a fast song. Then each soloist plays an improvised solo over a part or the full form of the song. Cats call a full cycle of a song one 'chorus.' And the stronger your chops, the more choruses you'll string together, becoming a masterful storyteller in music. Once the soloists have completed their parts, the melody of the song gets played and the band takes it out, slang term for ending a song together as a group. |

While performing in public, and when working with players of various skills, the cat who calls the tune usually plays the melody, and usually conducts the ending too. The drummer can always have the 'last say', to ensure a final stop. As jazz music is often a bit of a 'swirl of colorful musical sounds' to many listeners, so having the band start, and surely ending a song solidly together, helps make for a memorable experience for all within hearing distance :) |

2 and 4 / swing / half step lead in. In jazz, while there's a rhythm for 'everything' somewhere of course, most revolves around the big 4 and finding the 2 and 4 accent within these four beats of the 4/4 parade marching time. For this is where the swing lives for one and all :) Click time and explore these essentials and more. The 'half step lead in' is as its name implies; is a half step away from our target notes. So we can time our punctuations and resolutions from a half step away, really pulling on the time to bring the swing. This is perhaps the easiest trick in the book for blues and jazz guitar as our chord shapes are movable, thus easily slide in from a half step above to our target chord and notes. Master this one jazz guitar trick if no other. Looks and sounds like this. Example 21. This half step motion also has the greatest potential to get things up off the ground a bit and swinging. The 'tritone substitutions' are near the top of the 'half step lead in' devices. Single line players use time and articulation to master this swing magic potential, the half steps becoming a way of chromatic enhancement, to jazz up their lines and used delayed resolutions with time to bring the swing. Again and sorry to harp, but if ya learn no other 'jazz lick' here, master this half step lead in motion with a metronome, then use it, or not, as your musical tastes determine but at least you will have it under your fingers if ever needed. |

Single line / arpeggio / chord. These are the three main ways we group the pitches to express our ideas. Single note lines is mostly stepwise through scales. Arpeggios come from the scales and are sequenced in 3rds; major and minor leaps. Chords are simply sourced from the arpeggios and traced back to their parent scale; the pitches stacked on up and sounded together. Easy enough and with perfect closure to insure correctness. Looks like this. Example 22. |

Knowing this diatonic transformational theory cold, and throw in the five blue notes, is enough for some cats who just have a knack for music and a stick with it attitude for finding the sounds they need, to both support fellow musicians and express themselves as soloists, and be a team player thus part of the family. |

While this three part sequence of pitches; scales, arpeggios and chords, is a cornerstone of our theory, it also is a great way to build up a solo over a couple of choruses. Start with single line ideas, move into arpeggios and / or octaves and end with some well placed chords looking to drive the song's own sense of swing. Then maybe back to a bluesy single line idea to finish up and give the next soloist an easy start point (the blues) to begin their story. |

Wes Montgomery, a fingerstyle guitarist was a master of this sort of building of a solo. And coupled with the depth of his octaves and swing rhythm, his sound is unmistakable to the initiated. That with no pick for sounding pitches, Montgomery might have invented 'thumbstyle.' Which sounds a lot like fingerstyle but Montgomery is said to have mainly used his thumb for sounding his ideas. |

|

Single note melody lines, arpeggiate the chords, sound out blues licks, play melodies in octaves (his signature sound) and play fuller voiced chords. Nice palette of sounds and rhythms and never a worry about dropping our pick ! If you're reading here your leaning jazz ... find some Montgomery and just wear it out. Secret ... every jazz guitarist who could, has found some and done so. |

In jazz guitar and its improvisations, we can use all of these approaches in our work. The example which follows does just that; single line from a scale, it's arpeggio, some octave melody and then to an associated chord which resolves in the last bar. So, all combined, this next idea is a total mashup and so probably not very musical either, though can hear the changes in the line. What time's the bass player showing up ? :) Ex. 22a. |

The key shedding / technique strengtheners? Simple; where we change from one style of notes to another, single line to chord often termed to 'pepper in the changes' as in measure 1 through 4. Either one to octaves and back as in bar 5, chords to single note lines as in bars 7 and 8. These transition points are the tricky spots. Shed the transitions, just slow things way way down; one note / strum, one note / strum ... at a time. |

You'll be amazed how quickly you'll adapt. It's the same really as moving from one new chord shape to another; one strum then move, one strum then back, repeat. Down the road you might take five choruses on a blues so 60 measures or so; 2 or 3 single lines, 1 or 2 choruses in octaves, followed by chords and back to single line. Take me word for it, tis a tried and true, time honored tradition and formula, to building up an Americana jazz guitar solo thusly, although not in eight bars for the most part ... prolly need a few more :) |

Trio jazz guitar players, working with drums and bass, often excel at this weaving of the elements. Players such as Ed Bickert, Ted Greene, Jim Hall, Mark Whitfield, Pat Metheny, Bill Frisell, John Scofield have all memorably added to the library of the trio jazz guitar format. Explore the recognized masters and evolve. |

|

Jazz chords / movable shapes. In jazz guitar playing we love just about anything that we can move around as a 'complete something'; scale shape, arpeggio, chord etc. Generally, no more strumming a chord for even a bar or two :) For jazz songs, or even just the ones we jazz up, we use lots of different chords in progressions and even couple of key centers through modulation; we just like the variety of options. Everything included above is movable yes? Five scale shapes, 12 or so arpeggio shapes and the 15 voicings to cover the Two / Five / One motions. Develop a half step lead in technique and by golly be good to go ! |

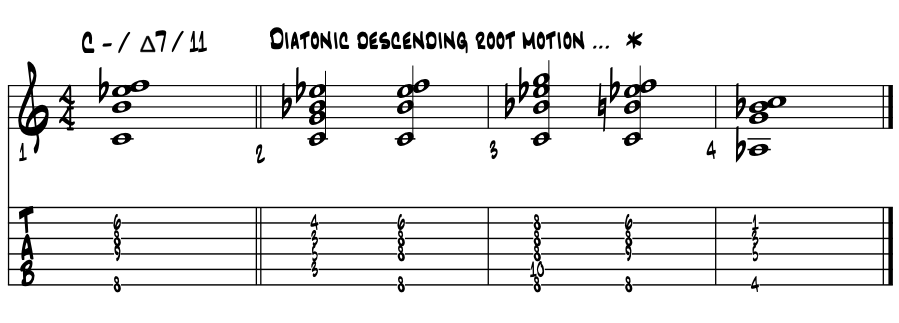

In learning these movable pieces, we simply start by thinking from the root, root position chords. And gradually build out from there into various inversions (movable too) and eventually to the 'one of a kind' puzzle pieces we each discover that only work in one spot in one song or two; here's one such lick. Ex. 23. |

Tangle up some fingers? While the 'C - / maj 7 / 11' is surely movable, it's a one of a kind for me because I've only really ever used it in this one spot in performing one song. Major 7 with 11 in the melody from a minor triad basis is somewhat rare in the literature. But jazz chords will solve these combinations of colors on guitar, become piano players in a sense. |

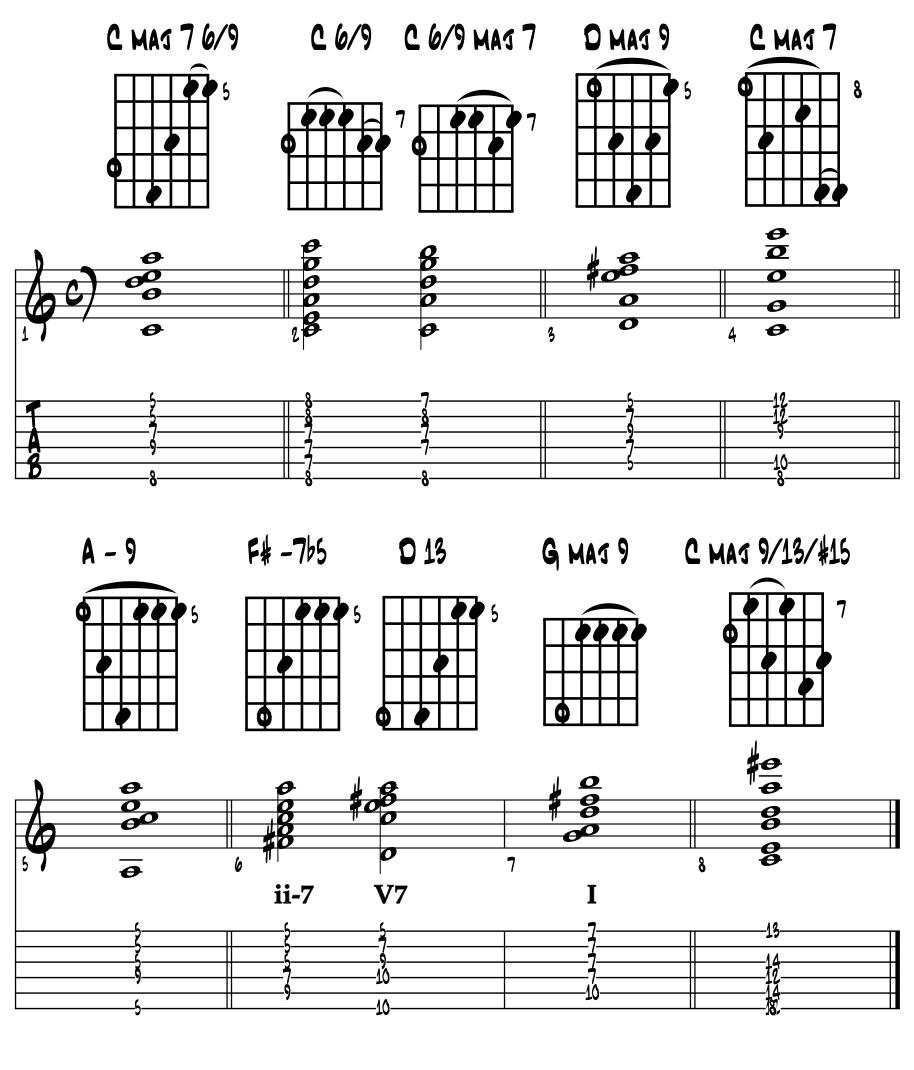

Hollywood chords. This is sort of a slang for uniquely voiced chords that jazz players love to impress one another with. At college, Dr. Miller would say, when reading through a song ... 'good spot right there for a Hollywood chord ol'e boy', pointing to spot on the chart. Then wow us with some octopus type looking chord who's sound defied reason back then. The few included here are ones that have stuck around over the decades (probably because I can still play them). Lucky, all of the included shapes are movable too, so they'll run up and down the neck as needed all the while retaining all of its qualities and magics. Here's a few. Example 24. |

Cool huh ? See any new shapes to explore? Cool. |