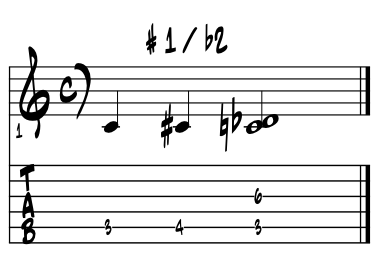

~ sharp One / flat Two ~ ~ #1 / augmented unison ~ ~ b2 / minor 2nd ~

'a halfway energizer between One and Two' 'What was, was.' 'halfway between diatonic One and Two ... '

|

In a nutshell, with a 'sharp one in the mix.' In the jazz vocabulary of colors there's a few ways to 'accelerate' the music, to make it sound as if it is going by faster, thus hopefully ramping up the excitement of the moment. In one sense we're just squeezing in a passing chord between the usual chords of common chord progressions. And yet, 'sharp One / #1', especially when a fully diminished 7th chord is employed, is the most common of our nitro burning accelerators. Author's note. Thinking major tonality here, near all of the theory principles that apply to this 'sharp One / #1' in the following discussions as a passing chord color will also work with passing chords built on 'sharp Two / #ii', 'sharp Three / #iii', 'sharp Four / #iv', 'sharp Five / #v' and 'Seven / vii.' So if ya dig the #1 motion, there's plenty more to discover yet still all within 'the spaces in between' the seven pitches of the diatonic realm. |

"Space has its own groove and swing." |

wiki ~ Wayne Shorter |

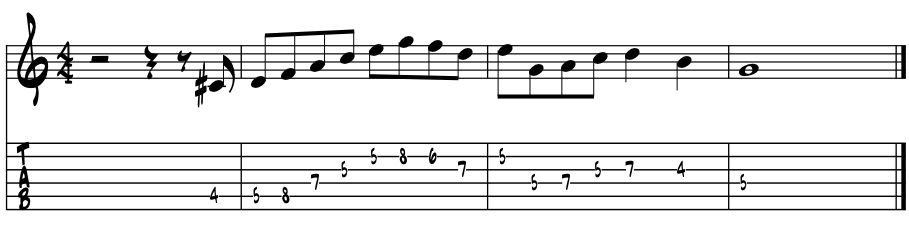

The basic function for a note, arpeggio or chord created on the #1 / b2 position is nearly always as a passing, non-diatonic element between One and Two. We can find the motion really anywhere in our music, though less so towards the folk side of things and lots more on the jazz side. Please examine its position within the letter pitches of the diatonic 'C' major scale. Example 1. |

|

Evolution of the artist. Sharp One is on the accelerator side of musical magics for sure. Most common ramping up is in a major key, to slip in a '#i dim 7' chord between One and Two. Just jazzing up our motion to Two by using the diminished color to zero in on where the music is going. "Hey Jay Bell" uses this #1 dim 7 motion in a jazzed up bluegrass setting. |

The other way, descending from say Two, we ramp down a bit before landing on One, and resolving as the case may be. For 'b2' is the root pitch for the tritone sub chord, flipping around the tritone pitches within the diatonic V7 to make a different chord and chromatic motion in the bass line. Again, it's really all jazz but some blues too, so if there's any blues in your musical weaves of Americana magic, maybe get hip to this chord substitution, built on the root of b2 and resolving by half step to One. For guitarists, the ' #1 / b2 tamale' is really the supreme, by 1/2 step, swing time rhythm accelerator. So, up or down by 1/2 step, give a booster to the rooster and all the dancers too. |

|

Theory names. This half step above the tonic is often simply referred to by its numerical designation. Generally we'll use the sharp (#) when ascending away from the tonic One towards Two so '#One.' And the flat (b) designation when descending from Two towards our tonic One pitch, so 'bTwo.' I'd also call this pitch a blue note, but I'm probably the only theorist that does. |

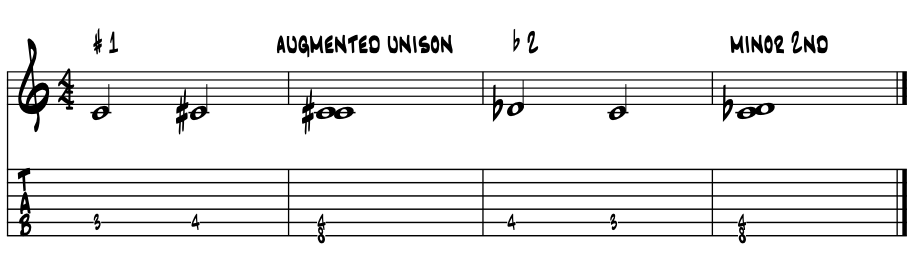

The sharp One interval. The theoretical distance between the tonic pitch and sharp One / flat Two is a half step, so a one fret distance on our guitars. Theoretical terms describing this interval include augmented unison and minor second. In motion, its termed chromatic, so by one half step. Example 1a. |

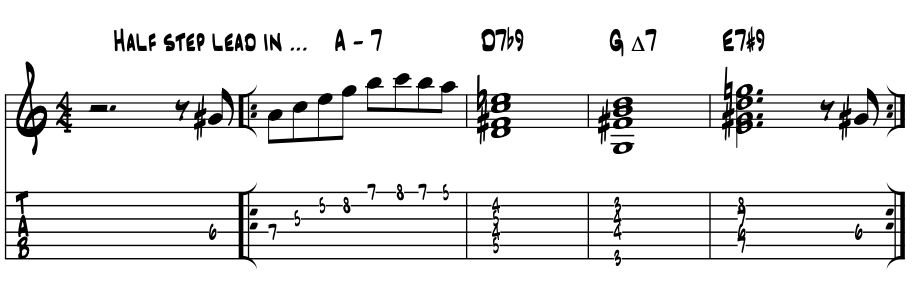

Half step lead in / melody. Melodically, we'll often use a pitch to anticipate the start of our line, we call this simply a half step lead in. While mostly a jazz and blues idea, it's just a natural way for giving our ideas a bit of a lift in getting started. The advancing theories of forward motion love this half step start to a line too, creating that something 'extra special' in the timing and phrasing of the music, found in all our Americana styles performed by seasoned artists in the know. |

Melody with #1/b2. In this next idea our #1 resolves upwards as a leading tone into Two, and the eighth note arpeggio to outline the chord tones. Here, starting on the 'and of 4' is cool and very classic. Example 2. |

|

In the above idea we do use the # One pitch for the half step lead in. Any of our pitches can often provide a similar lift to the line. Five to One is common as is the blue 3rd to major third also. Any of the 12 all are available of course. Some just more common that others, depending on the style. By half step is a good way to begin this 'jump start' process for our ideas. |

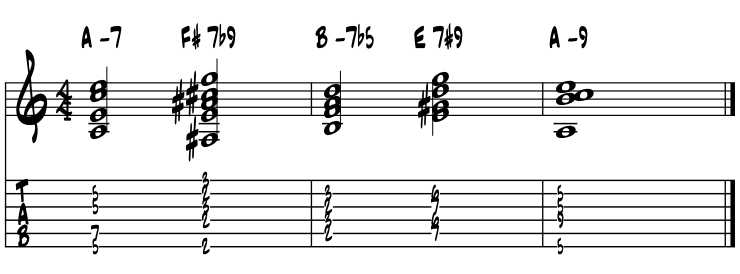

In this next idea we follow along the same lines but use a single line idea that merges with chords to complete the phrase. Thinking in 'A' minor. Example 2a. |

|

Sing the line. We can get a real feel for the energy of the sharp One idea by singing the line we're going to play. Often termed 'scat' singing, to sing the line then play the line helps insure our ideas speak from the heart. |

Harmony. In thinking chords, the half step motion has a few key aspects. As employed just above to jump start a line as a single note, we can do the same with the chords. As one of our essential 'great accelerators, we gain a few new, very cool, components simply by adding the half step motion into our mix. For in combining this simple motion with time and rhythm, we gain a rather robust way to energize our ideas. Bring it swing ? Yep. |

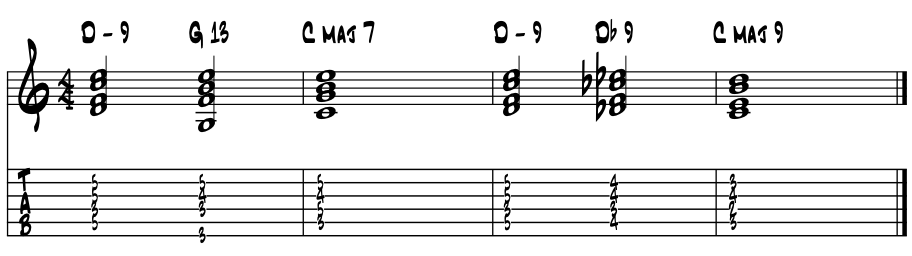

In the blues. In the blues, and really any of its genres and tempos, motion by half step is simply one of the core moves that helps the music groove big, stretch the time out. In this next idea, we use the half step motion from above to set up the One and (fast four) Four chords. The notation drives the quarter note rhythms on the beat. Click the pic for a live rendition of the following magic. Example 3. |

In this next idea we simply use the half step lead-in for our Two / Five / One cadential motion. Sharp One into Two, then from above down by half step to Five, the again from above into One. As guitarists, we'll generally use the exact same chord voicing for each of our half step motions. This type of voice leading is also often termed parallel motion or using a 'constant structure' as with the keyboard instruments. Example 3a. |

root motion by half step: |

C# to D

|

Ab to G

|

Db to C

|

resolution |

|

||||

The half step lead in as depicted above is one powerful component. While mostly in the realm of the jazz artist, it does find its way into the blues, especially when cats are working the 12 / 8 magic. As a rhythmic component, when used over a steady quarter note walking bass line, and 2 and 4 high hat drum groove, the half step lead in allows the chordal instrument in the mix, basically us and piano and vibes players, to judiciously sound their chords in anticipation of the bass and drums, oftentimes just a wee wee wee bit out front ... ? getting things to swing just right on the front half of the beat. |

Advanced players can and will often use this technique on all of the changes when performing. Add in substitutions and the various colortone possibilities and options can expand dramatically, with just a few components in place. As guitarists, our 'movable chord forms' make this half step process a snap. Much of this coolness is written right into the jazz language and literature. Learning tunes and explore opens the doors. |

|

Why in some cases, the Americana jazz music is so well crafted that all we have to do is push the written buttons on the page and the magic just pours right out, the swing is so deftly built right in :) The old time American classic "Careless Love" can truly be just such a song. |

|

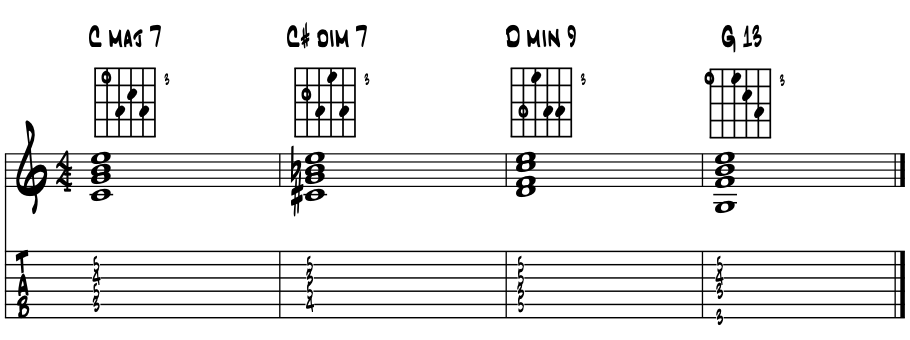

Sharp One diminished chord / major key. This next idea features perhaps the great accelerator of our more advanced Americana chord progressions. Kind of crazy how a relatively doable physical motion for guitarists can create such dramatic results in the positive energy and sense of forward motion we can gain for the music. Here we slip a fully diminished 7th chord between One and Two. Example 4. |

Feel the push on the energy of the music towards the Two chord? We get a chromatic motion in the bass, and chromatic is physically sleeker, sleeker can move faster. And notice how each chord has four pitches? This gives us a chance to use more of our fingers to start the music in motion. Of course a pick works too. Damping the strings between beats helps to articulate our timing. |

The above chord voicings are pretty standard, stock jazz voicings. All of these chords are root position and thus create a big, solid harmonic motion. These types of voicings, root position and also movable, and in such close proximity to one another, work super fine in many musical settings; with a big band, in the more ballad leaning tempos, and surely in rhythm sections with no other chordal instrument. |

In a big band setting, we're probably chomping four beats per chord in 4/4 time, a la Freddie Greene, to help drive and motor the groove / pocket along. There are initially three 'sets' of voicings for this progression for the evolving guitarist, each set capturing the root position, chromatic bass motion of the chord changes. We can initiate this motion from the 6th, 5th ( as in the example just above ) and 4th strings respectively. Click the link to the right to explore these motions. |

Sharp One diminished color in the line. Well, since we now have the chord in the phrase, why not add some of its super energizing color pitches into our melody line, jazz it up a bit, as it weaves through the changes. Here's a melodic idea slipping in the sharp One diminished motion as outlined in the chords just above. Example 4a. |

C maj 7 |

C# dim 7 |

D -7 |

G7b9 |

Scale shapes. Nice color yes? Inserting the diminished color surely spices up the line. We've a couple of additional ways to use this sound, the main one being in how there is a fully diminished 7th chord in the upper part of V7b9. Gaining this insight of b9, coupled with the multiple leading tone potential of the diminished color in V7b9, is oftentimes the next giant step in the theory for the advancing, jazz leaning guitarist. |

For in jazz guitar, one pedagogical approach is to master seven scale shapes. Five shapes cover the major / minor / modes and one scale shape each for augmented and diminished colorings. From these physical shapes we can generate both our most common arpeggio and chord shapes. We then begin the process of 'mix and match' between the shapes and search for the coolness within. We use this resource for writing and performing songs. |

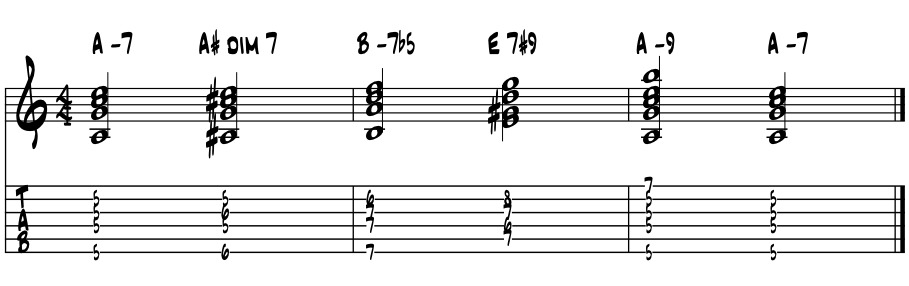

Sharp One diminished chord / minor key. Theory wise we use the same diminished 7th chord pitches for both our major and relative minor groups with one key center. The major 6th interval from major to relative minor inverts to a minor 3rd, the core interval for constructing our diminished colors, thus our chord pitches are identical. This next idea mirrors the above sharp One diminished motion but in the minor tonality. Example 4b. |

This sharp One diminished passing chord motion, in a minor key exampled just above, is not all that common in the literature. Actually, can't seem to recall having ever seen it or even playing it. Harmonically rather dense yes ? |

Sharp One diminished 7th = Six 7b9. What is super super common in the jazz literature is motion from a tonic minor One chord to VI7b9, so a basic One to Six? Yep. One to Six. These are the major / minor relatives yes? So share the exact same pitches? Sure do. In minor, Two is ii-7b5 half diminished to V7 altered, so knotty pitchwise and to understand too. That said, can we borrow this VI7b9 for a Two / Five in major ? Sure why not, for the 'b9' is a true power Americana blue jazz note n'est-ce pas? |

This is simply the very common and oh so essential motion of the One / Six / Two / Five chord sequence but here in a minor key, making it a wee bit more obscure. Let's examine the pitch relationships between the sharp One dim 7 chord ( #i°7) and the Six 7b9 (VI 7b9) chords. Example 4c. |

|

Simply different root pitches? So it seems mon ami. The bass line often tells the tale of a song's story. The chords built on them are often just different parts of arpeggios borrowed from one another. So in the upper part of our Six7b9 chord we've a fully diminished 7th chord? Yes, absolutely. For some reading here, this one bit of the theory will become a portal to a wider universe of music theory and a basis for chord substitution. |

We'll not only find this exact situation in the major keys but in all and any of our other various V7b9 chords as well. Here's a solution for subbing Six for sharp One diminished 7th ( #i°7) in a minor key. Do note that the root of our Six chord here is melodic minor based, not natural minor. Example 4d. |

An essential composition to learn. This last idea includes the opening changes to Thelonius Monk's "Round Midnight." A tune so well crafted and loved by players and listeners alike, that it is probably being played out in the world in a couple of places while you're reading this. For us guitarists, it is a great melody to play in octaves and also a possible chord melody too. Wes Montgomery had a nice hit with this composition. |

|

Author's note. There's a fluid spectrum of colors that floats the three basic forms of minor scales back to the major scale. This 'float' of course goes both ways. |

Sharp One Blue note. Not all too sure there is such a thing in our theories as a 'sharp One' blue note, maybe it's just a way sharp tonic pitch. Regardless, pushing the tonic up and then some more can raise some hairs and hackles and maybe even get the dancers a prancin'. I've seen it time and time again. We are not really talking a wide vibrato here, a la B.B. King, although that approach will surely push the pitch sharp. This is more deliberate, sharp and with some metal to the tone. |

|

As a mostly jazz flatwound player, I maybe bend a couple of pitches month. So this degree of bending is generally beyond my way of thinking and doing. My notation software won't go there so we'll have to go light strings to find this sweet spot, for those so curious. |

The flipside of sharp One is flat Two. The other side of the ascending sharp One position is simply to go the other way; by descending towards our tonic pitch from half step above. While we know the letter names of the pitches as enharmonic equivalents, and they are the same of course, in theory how we use and what we build upon them surely plays a role in their 'proper' identity. |

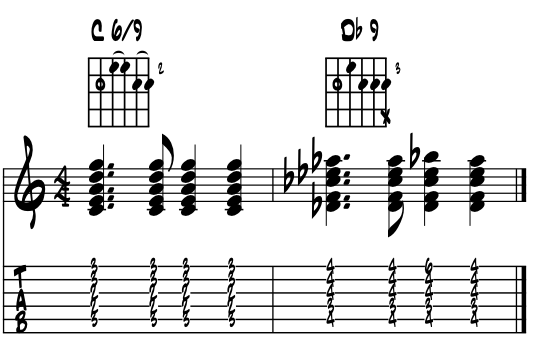

Montuno / flat Two. In this next idea, we create a basic montuno vamp that utilizes the tonic to flat Two motion we find within the Latin styles. We not only can readily find this motion within the literature but often will improvise such montuno vamps as intro's and outro's in performance. Example 5. |

These last two voicings are very solid bossa nova shapes. When played on a traditional bossa guitar, the nylon stringed classical guitar, they sound and feel warm, rich and solid. Once comfortable with the shape, try alternating the bass pitch between the tonic as shown in the example and the 5th of the chord, located on the lower 6th string. Oftentimes an easy do with giant results for this is a true core motion of bossa nova guitar :) |

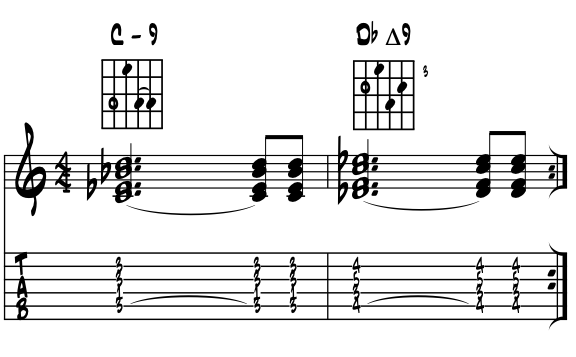

Montuno / flat Two / minor tonality. This next idea gets a lot of milage in jazz, especially in the last couple of decades or so. It also works well going in as an intro or out, as an outro to an arrangement of a song. Here we use the tonic minor 9th to major 9th coloring to set the mood. This type of coloring can work well in all sorts of grooves. Adjust the rhythm as your musical style demands. Easy alternating bass motion with these changes too. Example 5a. |

This motion might be a way into developing the ability to making the bar lines go away in your grooves. A tricky thing to do but one that many contemporary jazz cats love to do. Guitarist Pat Metheny just might be one of the original wizards who mastered this bar line magic and then consistently shared the magic globally. Note the triangle symbol for the Db major chord ? Just a shorthand symbol for major triad. The minus symbol (-) is a minor triad. Major and minor, Yin / Yang balance. |

|

Tritone substitution / flat Two / author's notes. Of all of the things I've learned over the years with guitar, it's a pretty safe bet that I've gotten more mileage out of the concepts surrounding the tritone sub than any other one theory component. Picking up the concept after a college big band rehearsal from trombonist, true friend and mentor Kirk Lamberti, I remember being simply stunned by a combination of its conceptual simplicity while sensing its eventual swing consequences on the music; 'sleeker is faster.' |

T'was amazing in how what little I had under my fingers that day dramatically evolved in that one spark of theory newness, creating a whole new dimension of musical coolness. This important evolution was not only in the tritone sub's cadential sound but somehow ... and this I don't fully understand yet ... it evolved my rhythm / chording / comping to swing ever so much harder. Perhaps this is part of the 'evolution of sleekness' of our musical components that artists have discovered over the last century or so. Sleeker trends to faster yes ? |

Simplistic beauty. We can initially illustrate the tritone sub in the essential jazz motion of Two / Five / One. All we'll do is replace our dominant / Five chord with another dominant chord type, whose root pitch is a tritone interval away from the written dominant chord. Thus the name of 'tritone sub.' It looks like this in letter names in the key of C major. Example 6. |

numerical chord progression |

Two |

Five |

One |

written changes |

D - 7 |

G 7 |

C major 7 |

tritone sub changes |

D - 7 |

Db 7 |

C major 7 |

|

Cool? Hopefully fairly easy to do for the most part. In jazz guitar studies we'll find this same basic tritone sub motion in each of our five major scale shapes and evolve the whole tamale from there. |

Why it theoretically works. Examining the pitches of the two dominant chords, the G7 and the Db7, we can see that the tension creating core of these two chords are the same two pitches. Example 6a. |

|

Three becomes Seven and the flip. Interesting huh? Not only are the roots of our chords a tritone interval apart but the pitches that work the magic within the chords are also a tritone apart. Those hip to this motion are of course already in the know. Cats just getting to this level of theoretical possibility should experiment with the changes and see if it will work in their music. Regardless of one's current theory hipness, there's a giant evolution of the harmony possible based on this initial chord substitution principle, one that just may be essential to the evolving guitarist within you :) As guitarist Jerry Levene might quip, "it lights the fuse." |

Chord type / 3rd and 7th. When we as theorists start to focus in on the third and seventh in our harmonic groupings, we open up the potential to discuss chord type, which simply becomes a numerical way to define any harmonic component's qualities. The core theory of chord type and chord quality is decided by simply determining the major / minor qualities of the third and seventh within any chord or arpeggio. |

Thinking along the lines of chord quality can put us in the theory bonus, as we now get to view things simply by mathematic interval, grouping like constructed components into unique families or categories of sounds and colors. Free from letter names, our theory machinations know no bounds. |

Theory cats think along the lines of chord type to; create a vocabulary of chord voicings that can function in similar capacities, find substitution chords as in the above tritone sub ideas, in streamlining the theory to a numerical perspective, helping to organize the shedding in preparation for performance, in soloing through chord changes as well as over the changes etc. |

Chord type in jazz. In jazz music and its performance, and of course depending on the players, time spent together, instrumentation, rehearsal time and the type of gig itself, when players see or think of a G7 chord, potentially lots of options can open up. There's G7 of course and its various voicings and inversions, the various color tones associated with the dominant harmony aspects of G7 and their inversions become possibilities, there's substitute chords with their color tones, voicings and inversions and further on into polytonal considerations. |

Our own evolution becomes based on what our ears will accept as cool and correct ... One way to explain this evolution might simply be, that if we took the first chord or chords we ever learned when we first picked up our gits, which for me was probably an open C major into an A minor chord, the "Teenager In Love" chords, and today 40 years later played the various ways I might play C major to A minor today, what I need to ask myself is that even if I knew then what would eventually become the hipper changes I know now, would my ears then have accepted the more advanced chords to function the same way in the music as the chords I first learned? Probably not. |

|

Could I have used my jazz voicings of today in that musical setting then? Probably not. So our way of hearing things, what our ears will accept as 'correct' for the music we're creating at any given point, will evolve over the years. This may be the initial case with accepting the flat Two, tritone substitution chord for V7 examined just above. |

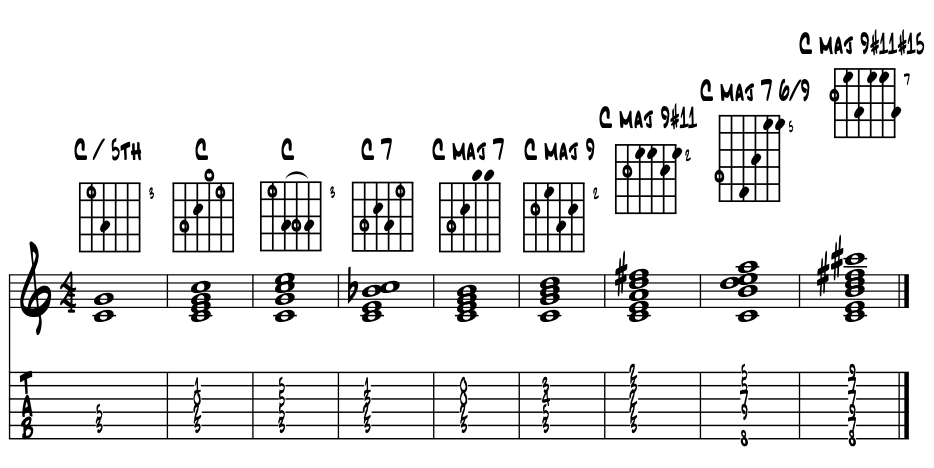

Of course the style of music we're playing is often the determining factor in the chords we choose. Maybe that's why we love the jazz language for its ever expansive nature of both discovered and to be discovered array of musical colors. But the digressed discussion here is more about one's own ability to handle the various degrees of stability and tension that our various chordal choices provide. To realize this evolution can exist, understand and dig this artistic evolution. Examine the following evolution of tonic function C chords in the major tonality. Example 7. |

|

From Metallic 5th's ... These chords are, in theory, tonic C chords for the key of C major, for all but the 5th's have a root pitch C and a major 3rd E in the voicing. Thus, they can function as tonal centers in C major. What we as artists are tasked to do, among many things of course, is find the chords that sound the proper degree of stability for the music we are performing. |

That way back in the beginning my first C chord of choice was the open C triad. Then I needed a blue 7th chord to hang in the blues music. Then a major 7th coloring to play pop and jazz standards. Then bored with major 7 colors things gradually evolved to became a bossa major 9. Then the polytonal #11 came along. Then that giant Hollywood 6/9 chord and tertian harmony evolved towards quartile stacking. Then through exploring theoretical discovery, that #15 monstrosity. |

So what do it mean ? Simply that our ever evolving ability to accept new colors, as in this example of tonic chord stability, helps us to evolve our art. Having this flexibility may also advance one's abilities to evolve melodies that are initially based on open C chords and reshape them to accept other less stable tonic support. |

And of course vice versa, better to understand how to stabilize the higher atmospheric ideas when they come along. To create melodies and music of a less predictable cadential nature which charts out our core theory evolution of our American styles. And that the ability to morph stylistically through the theory can continue to open new doors of creative exploration over the course of our careers. We simply strive to achieve a sense of the boundless potential available with the same basic core group of 12 pitches. |

In my world, John Coltrane's music creates the musical map that outlines the evolution in the tonic chord changes discussed above. Mr. Coltrane's biographers hip us to his work ethic, encouraging my direction of thought of how he simply exhausted things at each level, necessitating the creation of greater and greater challenges in the music he was creating, eventually looping back to starting off points for all of us. |

Luckily, we have his original compositions to study and recreate his evolution. Luckily we have recorded music, oftentimes live recordings, that includes his 'searching' and the exhausting of possibilities at each level of artistic development. That in many recordings we have Mr. Coltrane's tenor voice and ideas paired right next to Miles Davis' trumpet voice really helps things along. Side by side, by comparing their generally contrasting improvisational voices, Mr. Coltrane's searching, exhausting and eventual evolution of the music they were performing becomes even more evident. |

|

Review. The sharp One and flat Two positions in relation to our tonic pitch offer some interesting possibilities in regard to tension and release of the art we create. The diminished color has emerged yet again. The essential jazz tritone substitution has made a first appearance, creating a first step into the advanced evolution of Americana harmony as rediscovered and further advanced by John Coltrane. The montuno of the Latin / bossa flavors opens up a window to a whole new world, where our straight ahead jazz colors find a whole new set of dance grooves for exploration and enjoyment. |

|

"Space has its own groove and swing." |

wiki ~ Wayne Shorter |

Coda. Guitarist Charlie Christian might very well have had a strong hand in developing and establishing the tritone substitute to become a common sub for V7. His 1941 "Airmail Special" contains a bridge of chromatically descending fully diminished 7th chords, possibly replacing the cycle of dominants common in that era as modeled after the 1930 hit "I Got Rhythm," by George and Ira Gershwin, whose chord progression and form eventually became know as 'rhythm changes', providing a popular compositional form / model for jazz artists. |

|

The Latin influenced montuno, as its name implies, comes from the mountains. So we might conclude it has origins in the folk music. Of possibly Cuban descent, it has been mixed into the salza (sauce) of the Latin grooves we cherish today. With endless variations and its heart in the clave beat, musicians of many stripes dig the basic montuno vamp to help get the dancers up. While used in this discussion to describe a flat Two located musical device, this one location is just the tip of an iceberg of coolness for those still in the hunt :) |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

Find a mentor / e-book / academia Alaska. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music and can help you with your studies in the musical arts. |

|

Always keep in mind that all along life's journey there will be folks to help us and also folks we can help ... for we are not in this endeavor alone :) The now ancient natural truth is that we each are responsible for our own education. Positive answer this always 'to live by' question; 'who is responsible for your education ... ? |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

~ |