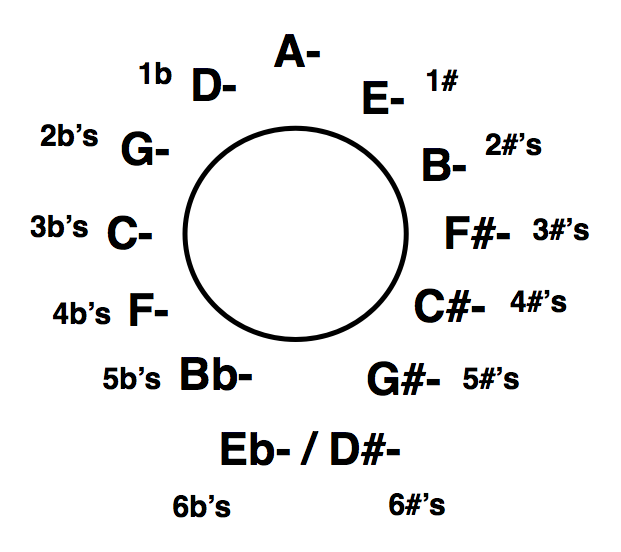

~ 12 paired key centers ~ ' ... leaning towards jazz in your studies ... ?

|

'here's our 12 pairs of keys, u got a fave yet ?

|

In a nutshell / key center. A key center is comprised of a set group of pitches, a 'key', that features one pitch as its tonal 'center', this we think of as One, while the remaining pitches of a 'key center' orbit around and create the various strengths of tonal gravities between the pitches. In modern day diatonic theory, key centers have seven unique pitches. Each of these we number, One through Seven, as measured from our center, One. Thinking in the key center of 'C' major, example one. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

So, a tonal center is really just a fancy theory term that organizes the pitches for creating our songs? Yep. We've 12 pitches in the chromatic scale, so we get 12 major and 12 minor centers, so 24 total. Each of the pitches of the chromatic scale can be the One, the root, the tonic note of a key center.

We choose a key center for a song usually by how the song first sparks to life, although with a bit of theory, movable scale and chord forms, or even just a capo, we changing keys is a snap. A song's chord progression, the pitch range of the melody paired with the vocal range of the singing artist, the 'mojo' of a key in relation to our instruments, all combine to find the right key center pitches to tell the tale. And then there's the 'movable one' if necessary. Once a key center is determined, the whole tamale of the theory falls into place. |

For with equal temper tuning, all the scales and their modes, their resulting arpeggios, all the triads and chords we create from these arpeggios, with their various color tones and alterations and voicing combinations, all of this resource we can equally project from each of the 12 pitches. So an awfully big tamale yes ? And with no creative mix and match limits, we're super golden. |

Leaning jazz and the 12 paired key centers. For jazz leaning learners there's at least two superior additional reasons to total understand this topic of key center. 1) It get's all 12 pitches under our fingers throughout the entire range of all of our chosen instruments thus; the 'anything from anywhere' concept of any scale, arpeggio or chord from any one of the 12 pitches fully manifests. 2) By getting to all 12 key centers in our musics, and especially in learning songs through a range of different keys, chances are good we can pick up a nice motif or two, a melodic idea, a 'turn of phrase' from each key's 'exact letter pitches' and know how to sound them on our chosen ax. For at some point along the way in learning the jazz language; its rhythms, melodies of songs with chords for jamming on, and improvising new melodies too, chord changes needing these exact same letter named pitches will surely come along. Placing / locating them from a melody and key center gives us something (anything :) under our fingers, gets us through that spot with a riff to weave into our lines. |

|

"Imagination is more important than knowledge." |

wiki ~ Einstein |

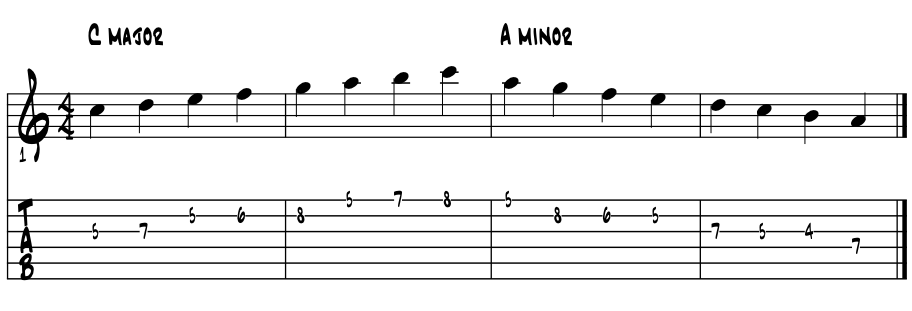

Relative major / minor. As songs are mostly written in a major or minor key, or a balance and pairing of both, our most common key center is built up with the pitches of the diatonic major / natural minor scale. This ancient grouping is also known to us today as the Ionian major / Aeolian minor modes, their modal identity from the olden days. In theory chart form and using letters and numbers, sketching out a modern key center's resources can often look like this, thinking 'C' major then 'A' minor. Example 1. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

A minor scale |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

A minor arpeggio |

A |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

chord # / quality |

i-7 |

vii-7b5 |

III |

iv-7 |

v-7 |

VImaj7 |

VII7 |

i-7 |

diatonic 7th chords |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

These last two charts are a nice bite of the whole tamale. Rote memorize these by speaking the letters aloud and writing out your own charts. By knowing how to create them, you've taken a giant step forward in understanding the nuts and bolts of our Americana musics. Throw in some blues hue and swing rhythms ... and off ya go :) |

We use a key center, with its own unique identifying key signature, to write a song down in music notation, which really is just a paper road map for how the song goes. Other players can then recreate this song from its map. Our standard notation of today creates the written paper 'recording' of the song to pass along to friends, colleagues, future generations of artists and to copyright. |

Quick review. Thanks to equal temper tuning, we get twelve equally unique and independent letter named pitches. And while we can expand this number by adding another octave or two, the basic theory of the 12 letter names always remains the same.

|

Theory overview. What a key center creates for us is a chosen, designated focus on one of our 12 pitches. For example, that a song is written in the 'key of C' tells us that the pitch 'C', is designated as that songs key center. Once selected, this pitch creates the center musical note from which the remaining 11 pitches are honorably beholden to. We term this centering on just the one pitch 'diatonic', and from this one pitch, in theory, we generate the 'diatonic realm', which becomes the pitch organization hierarchy of our songs. |

Simply identified by letter name, we create a key center by following our now ancient tone formula to create its core, mode, scale or 'group of pitches.' The seven pitches in this set group are termed diatonic, meaning 'through the tones', and in theory, form a perfectly closed looping of the letter name pitches. And the five pitches not yet included ... ? These become the blue notes. Combining the two we create one of those 'forever after' basis of understanding Americana music theory. That whatever comes along we'll have a reference point foundation to sort through the pitches of all music, find its rhythm magics and make it ours too. |

Scales / modes / arpeggio / chords. From each of the 12 key centers we get the exact same diatonic resource. Its seven unique scales include the relative major / minor and their modes. And of course, all of these scales reconfigure into their arpeggios, whose pitches are then segmented up and stacked into chords. |

Musical styles and composing. For guitarists, this instrument does many many excellent things in a number of ways. Our 12 unique key centers each have their own distinctive aural colors and depending on where sounded on the neck, composers of a style often work in select keys. Said composers who sing also, are also finding their keys to match up with their voices. Throw a capo and some open tunings into the mix, and off we go with a rather robust and unbreakable resource that can quickly adapt to our vocal range and ... handily go right on down the road. |

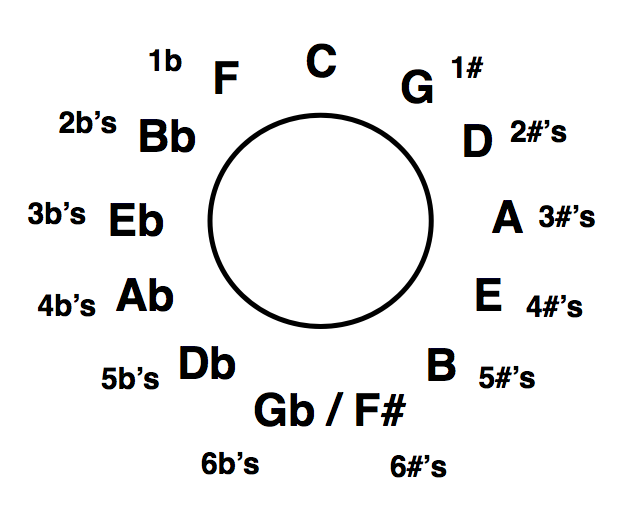

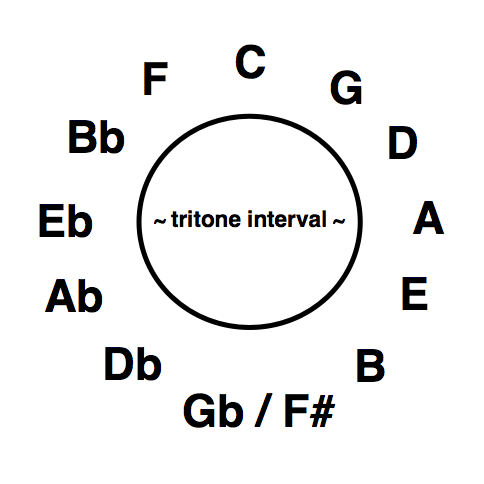

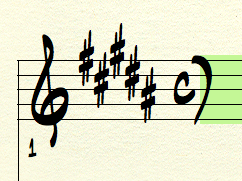

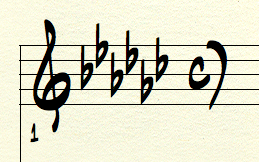

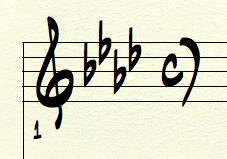

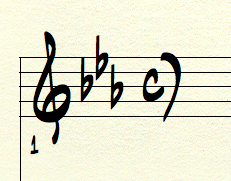

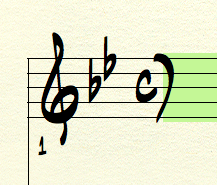

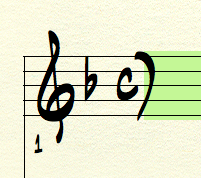

'G major E minor' key centers. For example, folk and children's songs love the open chords to back their story, thus 'C' and 'G' are the common major keys. Blues songs love the open chords too, which for our guitar often translates into 'E' and 'G.' These are the keys that our instruments are built in. Country music loves 'G.' Rock and beyond loves all of the above and surely into 'A', both major and minor, all things 'E' ~ 'B' and beyond. So in one sense, popular guitar key centers are moving clockwise on our circle of 5th's (shown just below here). Once barre chords, movable forms or a capo equivalent come into the mix, all the 12 keys open up, further adapting the guitar for any style in any key center. Jazz songs generally follow along with 'horn' keys so, 'C', 'F', 'Bb', moving counterclockwise on our circle of 5th's, as many different horns are built in the 'flat' keys. Those key centers are where we use the 'b' flat symbols to create the correct letter name pitches. Here's the 12 key centers by root letter name mapped out for major. We theorists call this picture puzzle the 'cycle of 5th's moving clockwise and 'cycle of 4th's moving counterclockwise. |

|

In storytelling. Somehow the right key center for a song seems to find itself. This is a big help. A song's words needs to find its own pitches. Once set into motion in time, the repetitive working out' of the idea generates its mojo. We theory cats turn this into a key center. |

How we then style or jazz up the story becomes the composer's art of weaving many things together. These often include; the vocals of the writer singing the story, instrumentation at hand, even an arrangement and orchestration of the song as resources permit. |

|

What follows. A most academic presentation of the nuts and bolts of our 12 key centers, paired as relative diatonic major and minor tonal environments. First there's a chart for spelling out the letter name pitches for each key's scales, arpeggios and chords. Also included are suggested songs for each key and some Jacmuse riffing on cliche Americana that happens in certain key centers plus ... whatever else shakes loose in our theorizing process of the magic we call Americana music. |

Creating a key center ~ a local universe. So just what is meant by the idea of a key center and how do we make one? A key center becomes like our own local universe of sun and planets, commonly termed our solar system. Our chosen key's letter name becomes the sun. Its other pitches become the planets. Their position within the key is simply determined by how far away from the center pitch they reside. These measured numerical distances become our musical intervals. It used to look like this out in space. Got a SWest comet in there too ! Prob-a-billy a chromatic tone passing ! |

|

Tonal destination. A key center also creates our tonal destinations when a song changes key, We usually use its dominant chord V7 to get there. In composing works, moving from one key center to another creates opportunities to explore, developing our melodies in ways that move beyond the initial diatonic realm or key center for a song. Common destinations include major / relative minor and motion to Four, the subdominant. Termed 'modulation', changing key centers is a powerful way to enhance really any event in the music, as our ears tend to 'perk up' when a new tonal center is sounded, even if the pitches are momentarily borrowed. And the V7 chord is the traffic cop directing key changes and modulation ? Yep. |

Tonal forces. And just as with our solar system, where there is a gravitational pull between the spheres, so to is there a tonal gravity between the pitches in a key center. We use this 'sense of pull' between the pitches to create the tension / release energy that powers our music along. How we shape this 'pull' within a tonal center, and in doing so creating tension and its release, is here often described as the 'aural predictability' of the music and further, correlates with music style. tonal gravity + aural predictability = style |

These two 'tonal forces', coupled with the number of pitches we choose to sound out our ideas, are a good part of the basis of musical style. For our various musical styles and crossover genres become the ways we tell our stories; of the society and ways of life, reflections of its peoples, inspirations of day to day way of doing things in that part of the world. |

The whole tamale ... what we get within one key center ~ a palette of the diatonic colors through and through. So in most every Americana song, in choosing one pitch to be the tonic pitch (One) of our song, we get the basis of what we need for composing most of the music we hear on the radio, at any given moment on any given day, across both the AM / FM broadbands. Here's the resource. Follow any of the links you are not familiar with yet, then bounce on back, or forward. 'Click and read' is the mantra here. |

Seven pitches to create a diatonic key center. Check. C D E F G A B C Seven modes? Check. Seven arpeggios? Check. Seven triads / chords? Check. Chord color tones? Check. Seven, full chord color tone arpeggios? Check. The 1 4 5 chord progression for major and minor. Check. A designated pivot chord between major ~ minor. Check. Seven select pitches. Check ... ooops back to start :) Cool? Lots of coolness to explore in a key center. |

~ three major / three minor chords ~ |

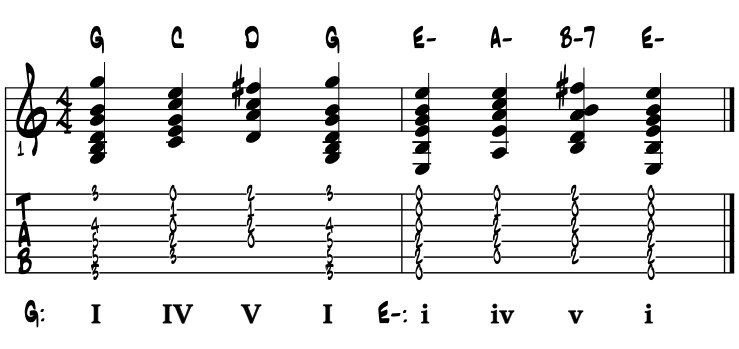

One / Four / Five chord progression ~ major and minor. Among the most essential secrets of our music theory is understanding that in any given key center, we get a One / Four / Five chord progression in both the major and minor tonalities for writing songs. As this harmonic motion / chord progression is most common all through our spectrum of styles of Americana, simply good sense to know of this theory and rote learn it now if need be. Please examine the pitches in 'G' major / 'E' minor and spelling the One / Four and Five triads / chords. Example 2. |

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

One / G major |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / C major |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

Five / D major |

. |

. |

D |

F# |

A |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

One / E minor |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / A minor |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

Five / B minor |

. |

. |

B |

D |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

Only a few places ... In so many of our Americana songs, these six chords have formed the harmonic basis, created the chord progressions for like a gillion songs. And as we look to the horizons for the songs to come, don't be surprised if these same chords show up again and again. For they go all the way back in our song book catalogue, no reason to think that it'll change any time soon. Master them here if need be. ( hmm ... why only six; G C D E- A- B- ??????? :) For across the spectrum from folk songs to pop, in keeping with a style's groove and vibe, with the chords, 'there's only a couple of places it'll go', as the diatonic realm rules the songwriting composing day for telling our stories. |

Borrow from another key center. Those looking to jazz things up will inevitably borrow pitches beyond the diatonic seven pitches and these One / Four / Five chords. That an identical harmonic resource is available with each of the 12 pitches as a key center is the resource we have today. |

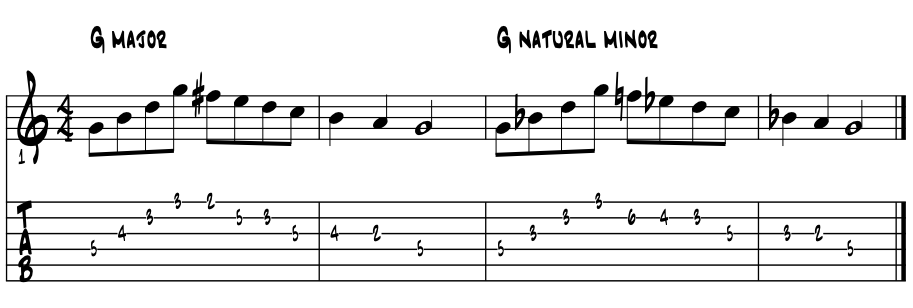

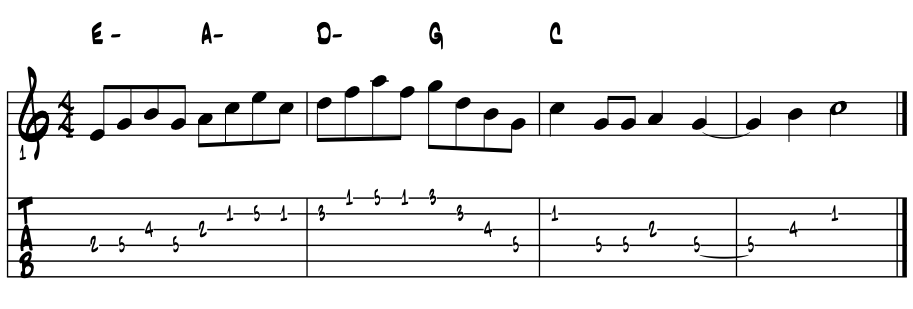

One / Four / Five melody scales ~ major and minor. Really just the same idea as above but included here for the non-chord instrumental artists. So, arpeggios? Yep, for the arpeggio players among us. Relative keys of 'G' major and 'E' minor. Example 2a. |

Relative and parallel keys. The idea of relative keys is really the gist of this discussion, pairing up the major and minor centers that share identical pitches. Parallel keys simply use the same root pitch and project various tonal centers and colors from the one pitch. Example 2b. |

Cool? Relative or parallel key centers. There's only these two, mostly. |

For the advancing reader. We theorists arrange our 12 pitches in a couple of key ways that can help shape our own 'big picture' of our art and music. U decide which. Thusly empowered, we can constellate any number of musical elements into a 'mobile of puzzle pieces', that floats right along in our own thought process as we compose musics. |

|

'No more no less ...' At the heart of our theory are the 12 unique pitches with which we create our musics, no more no less. Now an ancient format, we have cycles of the 12 pitches, such as this next pic of the cycle of fifth's. Seen this before now ? Yes. Cool. No ? No worries for ... This arrangement of the letter names organizes the pitches just like an ol' fashioned clock with 12 numbers. By thinking diatonic major scales and their key centers, the letter 'C' sits at the 12 o'clock position, as its seven pitches need no accidentals, no addition of pitch altering sharps or flats, to create the diatonic, relative major / natural minor scale formula. Example 4. |

|

Look familiar? Cool. No? Easy, begin to learn of it right here, looking to rote learn the diagram. Just get a piece of paper and pencil and draw the picture above. |

Now the minor keys. Similar format with 'A' natural minor. Located at the top of the clock as it uses no accidentals; sharps or flats to get the right pitches. Just like the pitches of 'C' major? Yep. Example 4a. |

|

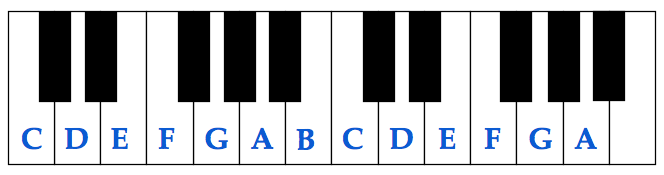

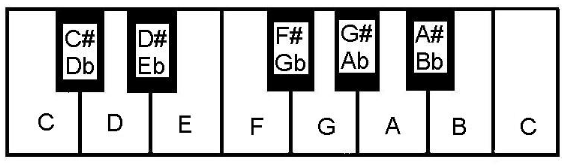

Cool so far? So 'A' minor and 'C' major share the same pitches? Sure do :) Remember the white keys on the piano? Example 4b. |

|

So built right into the white keys of the piano are the relative key centers of 'C' major and 'A' minor ? yep. And it has been this way for a long long time now, easily 1000 years or so. |

The 'jazz it up' chromatic. The chromatic scale is just another cool theory way to include all 12 pitches in a closed 'loop of pitches.' We design a loop by the interval / intervals in their composition, chromatic is by half step. While mixing sharps and flats accidentals together is generally a Bozo no-no, what with diatonic spellings and all, here's mix and match version to create a bit of confusion for U to sort through. So, are these letter names forming up the chromatic scale. Look familiar? Example 5. |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

C# |

D |

Eb |

E |

F |

F# |

Ab |

A |

|

Sharps and flats together? Yes agreed, a rather weird looking chromatic scale keyboard overlay, as we would exclusively using one or the other as is the norm in written music. We settle that when we choose a key center. For in a selected key center, there's little to no mixing of the sharps and flats together. Easier to notate thus less confusing. |

And then there's the super melodic complexity of the ... Charlie Parker Omnibook Containing transcribed jazz solos of the most advanced ideas in the 1940's, the Omni Book is written so that melody note pitch letter names align with the chord changes that support them, and the song's original key center, but ... there's no key signature in the score or staves. And then there's the blue note inflections to notate too. So ...? We just rote know both sharps and flats for each pitch, learn to spell out the letters of chords related to their diatonic key, and just be flexible, to sort out whatever combinations of pitch / letter / accidental notations that might come along. Understanding all of this level of complexity is based on knowing the principles of a key center, rock solid, set in stone, and surely on the 'to be rote learned' list. |

Running ideas / key centers. The 'running' of an idea through some sort of filter, such as the cycle of 5th's or chromatic / by half step, are simply ways that advancing artists practice or shed a motif they dig. Ever hear of to "run that idea through the 12 keys", from an experienced artist you admire? And while mostly a jazz thing, all artists can surely benefit from this practice and organization of one idea through various keys. For newby's here, beyond amazing how even just working an idea once through the cycle will broaden the horizons, show us areas we need to strengthen both in theory and on the fingerboard, and often generate new ideas along the way that might get the same 'running' sorts of treatment to generate a new idea. |

Running the changes of a song. Similar but different from the last idea, the 'running' of the chord changes of a song is something most jazz players love to do, though probably done in all of the styles too. This practice process, often done in time with a metronome, simply uses the chord changes of a song to generate improvised melodic ideas. We're just exploring the pitches in the context of music we love, looking for melodic ideas, patterns, sequences and other coolness that we can use when performing based on the harmony of a song. For the process of running the changes includes all of what we as improvising musicians do; exercise our physical chops, our mental connection to our hands and heart, finding the swing in a line, thus exercising the process of improvisation, all while moving through time and playing through the chords; wanting to hear the chord changes in the melodic line. |

Arpeggios tell the tale. In this next idea we 'run' the three note triads of a common turnaround of the pop and jazz language. Termed a '3 6 2 5 1', our root motion backpedals along the cycle of fifth's, 'C' major is our chosen key center and the letter name pitch that we're gravitating back to. Thinking 'C' major. Example 5a. |

Cool? Just using the pitches of 'C' major to outline each of the triads that we can diatonically build within this key center. |

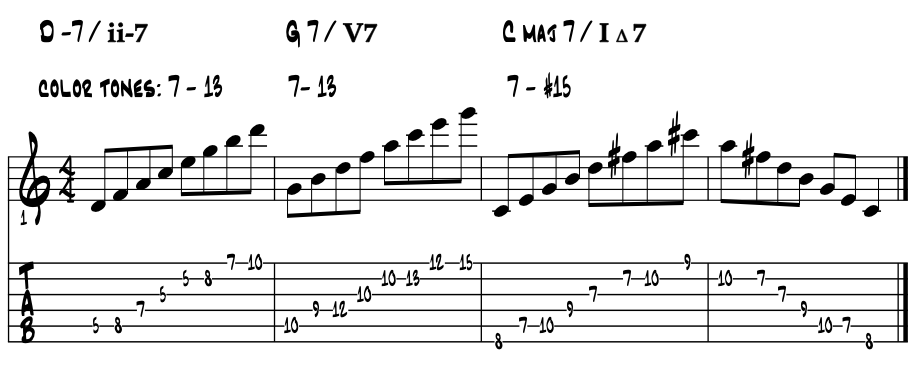

Revolutionized the music. There's a legend in our history / literature about how our Americana jazz dramatically evolved in the early 40's through this process of 'running the changes.' Alto saxophonist Charlie Parker said, that while he was warming up before a performance and running the changes to the then new song "Cherokee", of 1938 vintage, he hit upon the idea that he could extend his arpeggios into the upper color tones of each chord, opening up new melodic ideas, tensions, resolutions and blue coolness beyond. In this next idea we diatonically extend each of the chords of the Two / Five / One cadential motion in 'C' major. To 'jazz it up.' Example 5b. |

|

So all of this melodic resource is available, plus the blue notes, on every chord in a chord progression? Yep, potentially every chord. Style? Bebop :) |

Life beyond the triad. So this is often a natural process, moving beyond the pitches of a triad to add color tones. Our 'ears' need to understand and accept how a color tone fits in and works in creating harmonic motions such as; add the dominant 7th to each of the three principle triads for a 12 bar blues. Once to that level and style influence, adding in the pitches that reach further into the upper structure of each chord surely expands our creative palette as well as our range of musical styles. Oh, and in measure 3 above, the 'C' major 7, the #15 note is diatonic? |

~ 12 relative key centers ~ |

... '12 unique root pitches, 12 pairings of relative major / minor key centers, all based on the now ancient diatonic scale formula of whole steps (1) and half steps (1/2)' |

'The ancient diatonic scale formula is built right in.' Turns out that this ancient scale interval formula has been built into our keyboards all along the way, creating what might be the easiest series of pitches to find on any keyboard. Ancient and easiest. Imagine that :) For right under our noses, on a piano's keys, the ancient way our notes do lay. Example 6. |

So what follows here is an exploration of using each of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale and simply building a diatonic key center using the above scale formula. This scale is then transformed into its arpeggio and the seven diatonic triads are spelled out. |

|

C major / A minor. 'No sharps or flats.' So with no sharps or flats in the key signature, are these two key centers generally the easiest to 'theory cogitate' with? That's the idea. To just use the pure alphabet letters, old 'A B C D E F G A', it just makes it a lot easier to recognize when an accidental, a '# or b' is added into the mix. For then when we borrow a pitch to jazz something up, good chance it'll have a sharp or flat attached and thus jump right out on a written page of music. |

And for this very same reason, 'A and C' sit right atop at the 12 o'clock position of cycles of the perfect fifths and fourths etc., no sharps of flats, just the letters. Do these two paired key centers go all the way back to the beginning of time ? Probably. And for guitar, are there five core shapes puzzled together for the key centers of 'C major / A' natural minor on fretboard ? Absolutely. Which cover the pitches from stem to stern ? Indeed. Master the five and master the instrument. |

The key centers 'C major and A' minor are also among the most common for composition and performance. From songs for children and folk songs, right on through to jazz standards, the 'C' major scale sets the mood. Or off to the 'Fair', for 'A' minor. Please examine the basic theory of the spelling out of letter pitches, arpeggios and triads of these relative key centers. Example 6a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

triads |

C E G |

D F A |

E G B |

F A C |

G B D |

A C E |

B D F |

C E G |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

A- minor |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

A- arpeggio |

A |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

triads |

A C E |

B D F |

C E G |

D F A |

E G B |

F A C |

G B D |

A C E |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

Sound about right? Cool, yea very deep and ancient pitches. Got a few melodies for these key centers ? |

For guitar. And the 'five movable shapes puzzle' for the key center of C major / A natural minor ? Of course. The buttery gospel open shape for our 'C and A' pairing ends up at the 12th fret with tons of stuff in the middle. Always watch fret numbers for proper locations and think from the root of the chord / key center etc. Know the letter names yet? Click over to explore and rote up. |

|

|

Key centers of G major / E minor. A first clockwise click up an interval perfect fifth on our key clock and we find 'G' major and 'E' minor right at about 1:00 PM on our key clock dial. One sharp in the signature, our diatonic formula requires the half step leading tone motion from Seven to Eight close the octave. Compare the letter pitches of 'C' and 'G' major, as created by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 7. |

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

Note the bold type, in 'C' major our two natural, 'built in' half steps, follow the set in stone piano keys. For 'G' major, we need to raise the 'F to F#' to create the half step resolution to tonic. That each clockwise click of a 5th adds us our first new sharped pitch to our groups. And with clockwise clicks it is the ... 'click right ... 7th scale degree we raise by half step' Easy enough? Cool. A method to the madness? Always. Music and math? Same numerical theory in different key? Absolutely. Perfect closure to the theory? Always. In art? Well ... :) |

Here's a full charting of the pitches and basic sound of these essential key centers; 'G major / E minor.' Ex. 7a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

G arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

triads |

G B D |

A C E |

B D F# |

C E G |

D F# A |

E G B |

F# A C |

G B D |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

E- arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

triads |

E G B |

F# A C |

G B D |

A C E |

B D F# |

C E G |

D F# A |

E G B |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

Cool ? And is there a 'five movable scale shapes puzzle' for this key center too? Yep. Explore through the link. And the lovely Elizabethan era song "Greensleeves" is 'G' major / 'E' minor? Near every chart I've seen uses these key centers in writing this song. Barre chord 'G.'

|

|

Open tunings. These two centers also bring us to common open tunings for guitar, and especially blues guitar. The "g' key goes back to the old time banjo tuning, and the 'E' is standard, with a tweak, actually two tweaks and voila ... off to the slide and points beyond. |

Key centers of D major / B minor. The next click up a perfect fifth on our key clock and we find 'D' major and 'B' minor. Two sharps in the signature, again it's the Seventh scale degree that adds the new accidental. We need a 'C#' for 'D' major. Compare the pitches of 'G and D' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. And dig that mini pic .png of the cycle of 5th's :) Example 8. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

D major |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

Cool with this additive theory? Of the new sharp raising the 7th to being a half step below our tonic pitch 'D?' Same for every key? Yep, same for every key. That is until we get too many sharps and move over to using flats, to lessen the number of accidentals needed. Whatever is easiest to read and write, is the way we want to go. Now with two sharps, please examine the pitches for 'D major and B' minor. Ex. 8a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

D major |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

D arpeggio |

D |

F# |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

B |

D |

triads |

D F# A |

E G B |

F# A C# |

G B D |

A C# E |

B D F# |

C# E G |

D F# A |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

B minor |

B |

C# |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

B- arpeggio |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

B |

triads |

B D F# |

C# E G |

D F# A |

E G B |

F# A C# |

G B D |

A C# E |

B D F# |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'D major / B' minor. |

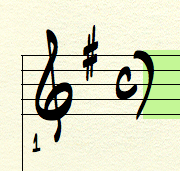

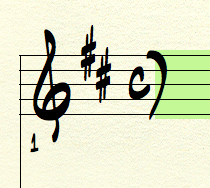

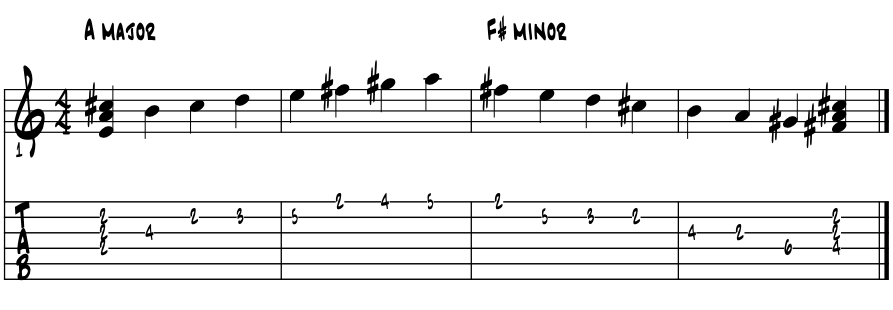

Key centers of 'A' major / 'F#' minor. Taking the next click up a perfect fifth on our key clock and we find 'A' major and 'F#' minor. Three sharps in the signature, again it's the Seventh scale degree that adds the new accidental to our pitches. Compare the pitches of 'D' and 'A' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 9. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

D major |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

A major |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

So one by one we add a new sharp, adding to the one's we already have. Now with three sharps, examine the pitches of 'A major / F#' minor in the following chart. Example 9a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

A major |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

A arpeggio |

A |

C# |

E |

G# |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

triads |

A C# E |

B D F# |

C# E G# |

D F# A |

E G# B |

F# A C# |

G# B D |

A C# E |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

F# minor |

F# |

G# |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

E |

F# |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

F#- arpeggio |

F# |

A |

C# |

E |

G# |

B |

D |

F# |

triads |

F# A C# |

G# B D |

A C# E |

B D F# |

C# E G# |

D F# A |

E G# B |

F# A C# |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

|

'A major / F# minor.' |

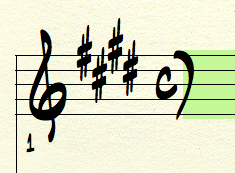

Key centers of 'E' major / 'C#' minor. The next click up a perfect fifth on our key clock gets us to about 4 o'clock, where we find the 'E' major and 'C#' minor groupings. Four sharps in the signature, and yet again it's the Seventh scale degree that adds the new accidental. Compare the pitches of 'A' and 'E' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 10. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

A major |

A |

B |

C# |

D |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

E major |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

So one by one we add a new sharp, adding to one's we already have. Now with four sharps, please examine the pitches of 'E' major / 'C#' minor in the following chart. Example 10a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

E major |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

E arpeggio |

E |

G# |

B |

D# |

F# |

A |

C# |

E |

triads |

E G# B |

F# A C# |

G# B D# |

A C# E |

B D# F# |

C# E G# |

D# F# A |

E G# B |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C# minor |

C# |

D# |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

B |

C# |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C#- arpeggio |

C# |

E |

G# |

B |

D# |

F# |

A |

C# |

triads |

C# E G# |

D# F# A |

E G# B |

F# A C# |

G# B D# |

A C# E |

B D# F# |

C# E G# |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

|

'E' major / 'C#' minor. |

|

Key centers of 'B' major / 'G#' minor. The next click up a perfect fifth on our key clock gets us to about 5 o'clock and we find the 'B' major and 'G#' minor groupings. Five sharps in the signature, and yet again it's the Seventh scale degree that adds the new accidental. Compare the pitches of 'E' and 'B' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 11. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

E major |

E |

F# |

G# |

A |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

B major |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

So one by one we add a new sharp, adding to one's we already have. Now with five sharps, examine the pitches of 'B' major / 'G#' minor in the following chart. Ex. 10a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

B major |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

B arpeggio |

B |

D# |

F# |

A# |

C# |

E |

G# |

B |

triads |

B D# F# |

C# E G# |

D# F# A# |

E G# B |

F# A# C# |

G# B D# |

A# C# E |

B D# F# |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G# minor |

G# |

A# |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

F# |

G# |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

G#- arpeggio |

G# |

B |

D# |

F# |

A# |

C# |

E |

G# |

triads |

G# B D# |

A# C# E |

B D# F# |

C# E G# |

D# F# A# |

E G# B |

F# A# C# |

G# B D# |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

|

B major / G# minor. |

Key centers of 'F#' major 'D#' / minor. The next click up a perfect fifth on our key clock gets us to 6 o'clock and we find the two letter choices for our tonic pitch. It's a bit of a toss up really, as each of the pitches create a diatonic key center with a six necessary accidentals. Just a a whopper of a key signature. We can go on beyond six, 'C#' major would have seven yes ? Yet its enharmonic equivalent 'Db' has only five b's, so a bit more civilized, thus easier to read. They do share the same five diatonic scale shape sequence for guitar, thank goodness. So the key of 'C#' major is a non-starter? Yep. 'C#' minor? Quite popular really, and the key center of some classic songs that have long stood the test of time. Example 11. |

|

|

|

So either way, 6b's or 6#'s, our written notation is going to be busy. Also, while we moved a perfect fifth to get from 'B' to 'F#', the relationship at '6 o'clock' from our starting point 'C' is surly worth noting. Polar opposites you say? Kind of yes. So polar opposite sounds in a key center? Key schemes hmm ... do composers ever 'scheme' keys together based on some theory nonsense? That would all indeed, seem to often be the case. Can we flip to relative minor pitches and perspective here and still be theory correct and recognize the proper interval ? So 'C' to 'Gb' becomes 'A' and 'Eb?' Please examine this next diagram. Example 11a. |

|

Measure the interval from 'A' to 'Eb' straight across equals 'C' across to 'F# ?' 'C' to 'Gb?' It must ... and of course it does. Tritones? Yep, tritones. Go there and explore the 'polar' pitch to any chosen key center. |

| So now six sharps in the signature, and yet again it's the Seventh scale degree that adds the new accidental. Compare the pitches of 'B' and 'F#' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 11c. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

B major |

B |

C# |

D# |

E |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

F# major |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

C# |

D# |

E# |

F# |

Yikes an 'E#.' And an 'A#' too. They are rare. 'E#' is of course also 'F' natural. 'A#' is 'Bb' too, enharmonic equivalents as we theorists say.

|

Now with six sharps, examine the pitches of 'F#' major / 'D#' minor in the following chart. Ex. 11d. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

F# major |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

C# |

D# |

E# |

F# |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

F# arpeggio |

F# |

A# |

C# |

E# |

G# |

B |

D# |

F# |

triads |

F# A# C# |

G# B D# |

A# C# E# |

B D# F# |

C# E# G# |

D# F# A# |

E# G# B |

F# A# C# |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

D# minor |

D# |

E# |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

C# |

D# |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

D#- arpeggio |

D# |

F# |

A# |

C# |

E# |

G# |

B |

D# |

triads |

D# F# A# |

E# G# B |

F# A# C# |

G# B D# |

A# C# E# |

B D# F# |

C#E#G# |

D# F# A# |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

|

'F#' major / 'D#' minor. |

Key centers of 'F#' = 'Gb' major / 'D#' = 'Eb' minor. A deja vu moment ? Almost :) But no, just stopping to compare the key of 'F#' with its six sharps to 'Gb' with its six flats. The root notes of 'D#' and 'Eb', covering the minor tonality pairing. Dig the visual transition point to flats on our cycle of fifth's, right at about 7:00 PM. Example 12. |

|

|

Coming around the half way mark the flats arrive. Do we ever mix sharps and flats in written music? Super rare in diatonic scores but yes. Music notated without a key signature often needs both sharps and flats to get it all right. Mostly a jazz thing? Yep. |

| So now six sharps in the signature, and yet again it's the Seventh scale degree, the leading tone, that adds the new accidental. Compare the pitches of 'F#' and 'Gb' major by the diatonic scale's interval formula. Example 12a. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

F# major |

F# |

G# |

A# |

B |

C# |

D# |

E# |

F# |

Gb major |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Yikes, now a 'Cb.' A never seen, super rare musical note / letter, even in theory and jazz. Just confusing and there's a better way. Well at least 'E#' is now 'F', that helps mucho. Well let's go through 'Gb' major / 'Eb' minor letter pitches, following our same process for creating their diatonic scale, arpeggio and spelling out their triads. |

Now with six flats, examine the pitches of 'Gb' major and 'Eb' minor in the following chart. Example 12b. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Gb major |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Gb arpeggio |

Gb |

Bb |

Db |

F |

Ab |

Cb |

Eb |

Gb |

triads |

GbBbDb |

AbCbEb |

BbDbF |

CbEbGb |

Db F Ab |

EbGbBb |

F Ab Cb |

GbBbDb |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Eb minor |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Eb - arpeggio |

Eb |

Gb |

Bb |

Db |

F |

Ab |

Cb |

Eb |

triads |

EbGbBb |

F Ab Cb |

GbBbDb |

AbCbEb |

Bb Db F |

Cb Eb Gb |

Db F Ab |

EbGbBb |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

Gb major / Eb minor. |

|

Key centers of Db major ~ Bb minor. Well as we can see as we head back towards the top, where 'C' reigns in non-accidentalness, With 'Db' / 'Bb'-, we loose a flat; from the six of 'Gb' to five for 'Db' and 'Bb-.' Here we evolve the pitches. And still the 7th scale degree is the new pitch for each succeeding key by fifth. Example 13. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

Gb major |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

Cb |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Db major |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Back to a 'C' natural. Whew. Easy to tangle up with some of these combinations. Know any songs in 'Gb' or 'Db?' 'Eb' or 'Bb' minor? Not all that common for key centers but surely we can borrow a bit from here or anywhere for that matter to spice up whatever. |

Now with five flats, examine the pitches of 'Db' major and 'Bb' minor in the following chart. Ex. 13a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Db major |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Db arpeggio |

Db |

F |

Ab |

C |

Eb |

Gb |

Bb |

Db |

triads |

Db F Ab |

EbGbBb |

F Ab C |

GbBbDb |

AbCEb |

Bb Db F |

C Eb Gb |

Db F Ab |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Bb minor |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Bb - arpeggio |

Bb |

Db |

F |

Ab |

C |

Eb |

Gb |

Bb |

triads |

Bb Db F |

C Eb Gb |

Db F Ab |

EbGbBb |

F Ab C |

GbBbDb |

Ab C Eb |

Bb Db F |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'Db' major / 'Bb' minor. Know any songs in 'Db?' |

|

Key centers of 'Ab' major ~ 'F' minor. At 8 o'clock, we find 'Ab' with its four flats. While not uncommon as a key center, it is the Four chord of 'Eb' major, a quite common jazz key as it puts the transposing horn players in very comfortable realms of pitches. The key center of 'F' minor is also fairly common throughout the literature. For guitar and bass players, even though there's no b7 below the two tonic pitches on the outer 'E' strings, we get the full force of the blues in first position. A jazz cats, blues in 'F' is common. Please examine the pitches of 'Ab' evolving from 'Db', again the half step positions within the formula define diatonic. Example 14. |

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

Db major |

Db |

Eb |

F |

Gb |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Ab major |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Here we pick up 'G' natural, the leading tone for 'Ab' major. Now with four flats, examine the pitches of 'Ab' major and 'F' minor in the following chart. Ex. 14a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Ab major |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Ab arpeggio |

Ab |

C |

Eb |

G |

Bb |

Db |

F |

Ab |

triads |

Ab C Eb |

Bb Db F |

C Eb G |

Db F Ab |

Eb G Bb |

F Ab C |

G Bb Db |

Ab C Eb |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

F minor |

F |

G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Eb |

F |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

F - arpeggio |

F |

Ab |

C |

Eb |

G |

Bb |

Db |

F |

triads |

F Ab C |

G Bb Db |

Ab C Eb |

Bb Db F |

C Eb G |

Db F Ab |

Eb G Bb |

F Ab C |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'Ab' major / 'F' minor. |

|

Key centers of Eb major ~ C minor. Now right around the 9 o'clock click, we find 'Eb' with its three flats. 'Eb' is a important key for jazz players. There's just some great songs written in 'Eb.' From top 10 super ballads to the hard bop of the 50's, 'Eb' is a handy choice, whose pitches lay out very well on our guitars. The key center of 'C' minor is, as one might well imagine, very very important. For with 'C' minor pentatonic so close to the blues group, anything in 'C' with a hint of the blues will probably find some of these 'C' minor notes too. So why not just think chromatic? Well we could, but for many of us, there's just a necessary evolution to get to that level of hearing and understanding chromatic lines. In chromatic lines we loose the sense of tonal center. Which is why we be here in the first place yes ? Please examine the pitches of 'Eb' evolving from 'Ab', again the half step positions define diatonic. Example 15. |

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

Ab major |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

Db |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Eb major |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

Here we pick up 'D' natural, the leading tone for 'Eb' major. Now with three flats, examine the pitches of 'Eb' major and 'C' minor in the following chart. Ex. 15a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Eb major |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Eb arpeggio |

Eb |

G |

Bb |

D |

F |

Ab |

C |

Eb |

triads |

Eb G Bb |

F Ab C |

G Bb D |

Ab C Eb |

Bb D F |

C Eb G |

D F Ab |

Eb G Bb |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C minor |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C - arpeggio |

C |

Eb |

G |

Bb |

D |

F |

Ab |

C |

triads |

C Eb G |

D F Ab |

Eb G Bb |

F Ab C |

G Bb D |

Ab C Eb |

Bb D F |

C Eb G |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'Eb' major / 'C' minor. |

|

Key centers of Bb major ~ G minor. Now right around the 10 o'clock click, we find 'Bb' with its two flats. 'Bb' is oftentimes, along with 'C', a 'jump' key, so named for the musical style of the 1940's that came out of Kansas City. 'Bb' is also very a common jazz key for the 12 bar blues, in any tempo really. Are there rockin' 'jump 12 bar blues' in 'Bb?' For sure. Some now classic and early rock-a-billy is in 'Bb'; Chuck Berry recorded his essential "Johnny B. Goode" in 'Bb', as is its live cover by the Grateful Dead. This 12 bar rockin' blues in 'Bb' is one of the songs that started it all. The key center of 'G' minor, is for all string players, as one might well imagine, just very very important. For just like 'C' minor, which precedes in the cycle, the 'G' minor pentatonic group of pitches is just one note shy of a true blues scale. And with its pitches tuned up near to 'A' = 432 cycles, and not the standard 'A = 440', per second, they'll go all the way back through our collective histories to our banjo days. So folks have been hearing these pitches, tuned original tuned pitches, so as such gets a lot of work in Americana as the same few pitches go all the way back. 'G'- is also a fairly common reggae key, with its comfortable 3rd position barre chords and scale shapes. Even up the octave near the 15th fret is, with practice, accessible on any modern sort of electric guitar to help climax a ride. Examine the pitches of 'Bb' evolving from 'Eb', again the half step positions define the diatonic. Example 16. |

|

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

Eb major |

Eb |

F |

G |

Ab |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

Bb major |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

Here we pick up 'A' natural, the leading tone for 'Bb' major. Now with two flats, examine the pitches of 'Bb' major and 'G' minor in the following chart. Ex. 16a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Bb major |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

Bb arpeggio |

Bb |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Eb |

G |

Bb |

triads |

Bb D F |

C Eb G |

D F A |

Eb G Bb |

F A C |

G Bb D |

A C Eb |

Bb D F |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G minor |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

G - arpeggio |

G |

Bb |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Eb |

G |

triads |

G Bb D |

A C Eb |

Bb D F |

C Eb G |

D F A |

Eb G Bb |

F A C |

G Bb D |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'Bb' major / 'G' minor. The fret location of this last idea is right in the blues and butter of movable shape five. |

Key centers of F major ~ D minor. Right at the penultimate position of 11 o'clock, we find 'F' with its one flat. 'F' is common as a key center. It is a gospel key, earthy and with a good range of pitches for voices. It transposes well for horns and on guitar, its pitches run nicely from the first fret right on up the octave. The key center of 'D' minor is as one might well imagine, very very important. While the open triad / chord for 'D' minor works fine as a tonic chord, we often find it as the Four chord in 'A' minor, which goes all the way back. Please examine the pitches of 'F' evolving from 'Bb', again the half step positions define diatonic. Example 17. |

|

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

Bb major |

Bb |

C |

D |

Eb |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

F major |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

E |

F |

Here we pick up 'E' natural, the leading tone for 'F' major. Now with one flat, examine the pitches of 'F' major and its paired relative 'D' minor in the following chart. Ex. 17a. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

F major scale |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

E |

F |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

F arpeggio |

F |

A |

C |

E |

G |

Bb |

D |

F |

triads |

F A C |

G Bb D |

A C E |

Bb D F |

C E G |

D F A |

E G Bb |

F A C |

chord quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

D minor scale |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

D - arpeggio |

D |

F |

A |

C |

E |

G |

Bb |

D |

triads |

D F A |

E G Bb |

F A C |

G Bb D |

A C E |

Bb D F |

C E G |

D F A |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

'F' major / 'D' minor. |

|

And back to the top we go and find 'C' major / 'A' minor at our 12:00 position. A most remarkable thing about going through this information from stem to stern, is that while one might not have it all too well memorized in one pass, we touched them all. So there's a chance if we ever need the info of a 'remote' key center, or any key center for that matter, we'll know where to find it or even better, know how to conjure its letter pitches up from scratch, using our scale formulas, what we music theorists generally love to do, conjure it up from scratch, sift through the pitches, start off grooves right out of thin air, have a way to hear a music and find a way into its structure, or not and let it just float on by, as the case might be. |

Key centers and musical styles. While there's just lots of factors to consider in determining why a certain key center is chosen for a song, stylewise and instrument wise, there's some common ground here. And while all are valid from some perspective, a big chunk of this 'deciding' is about the nature of the story to be told, and the style of music in we decide tell it in. And of course the writer or 'teller' gets final say. And for guitar, then there's the capo :) |

Folk keys. Folks songs, and also children's songs, usually end up in keys of the open position chords. Mostly two or three chords and the truth, the melody is usually sung by the artist and not instrumentally sounded out. Transposition and or a capo makes all this negotiable into other key centers. Most important in all this is the singer's choice of keys; to found the good pitches for this song in their range, to interpret the melody pitches and lyrics of the story. |

Bluegrass and country keys. A lot of this music favors the 'sharp' leaning keys. For it gives the bass player some open strings to work on the doghouse bass fiddle. So, the 'G / E' minor pairing is a clear favorite. 'C' and 'A' minor, 'D' / 'B' minor. 'E' is a common key here too for country. There's a school of 'Tele' guitar that never gets above the fifth fret. Most important in all this is the singer's choice of keys, as the vocal line is the storyline. |

Blues keys. Today, blues keys usually start with 'E', as the open chord and blues scale shape is core Americana. For electric players, this all can jump to the 12th fret with the greatest of ease. And then lookout :) Blues songs in 'G' blues is common, as we get an open 'G' tuning from the original blues artists from the banjo days. Blues in 'A' blues puts us right at the 5th fret. Both super cruise right up an octave for the exact same shape to the 15th or 17th frets respectively, right near the tippy top for Strat's, Tele's and Les Paul's. There's some great blue notes up there, tricky to locate and get to sound, but worth the search. |

Rock keys. Anything blues is going to be rock too. Country rock adds more of the diatonic into the mix and their keys as well. Mostly sticking to the clockwise sharp side keys of the cycle? Yep. Most important in all this is the singer's choice of keys. 'E' prolly tops the list and Country on a Tele loves 'A' too. |

|

Pop keys. Rarely ever an instrumental song, there's really no favorite keys in pop music as much is determined by the voice that is going to sing the lines. Whatever key is best for the singer is a place to start. With all the electronic gear potentials these days; transposers, tuners, pitch tweakers et all, different keys in producing pop music is not anyone's problem really, unless the range of the voice conflicts. If so, just adjust to the voice, simple. Nine out of ten times, most important in all this is the singer's range of pitches, their vocal 'range.' Plus their 'shalimar' range (?), their best couple of pitches. Ya got's u a best note yet ? |

|

Jazz keys. All 12 keys, both major and minor, are potentially in play in creating jazz. And this is one of the aspects that jazz artists / players love about their jazz musics. Everything is in play all the time, pitches, arpeggios, chords, substitutions, time, variations and forward motion techniques and ... we get to make it up, from our shedding and rote memories, as we go along. Pretty nice art form huh ? And while sharp keys are cool, especially for string players, the flat keys favor the horns. For they are built in selected keys. Horns built in 'Bb' include trumpet, tenor saxophone and clarinet. Alto sax is built in 'Eb.' These are transposing instruments. So lucky for us 'chord players', guitar and piano mostly, our instruments are designed to play it all really; all the notes, all the keys and all the chords with any sorts of instruments that might ever come along. |

|

Also in jazz musics, there's also just a much stronger potential to 'borrow' bits from different keys and place them into the song we're performing. And two or three key centers in a jazz tune is not uncommon. In jazz blues, the high degree of chord substitution available opens up all kinds of borrowing of pitches and bits of keys, however momentary, in the actual music. Again, important in all this is the singer's choice of keys, or the horn player for that matter, as a lot of jazz is instrumental music. |

The 'movable One.' At rehearsal a few months back, while working out an original song of 'King Kev', our area Alaskan reggae maestro from NYC, quipped to moi the bass player, 'why ... tis the 'movable One' my good sir, same bass line please, just from 'G' instead of 'E.' So afterward I asked the King about this 'movable One.' And it turns that it's the way he learned to understand and describe the idea of having a key center, a central pitch, One, in our songs. So, I 'transposed' the song from 'E' to 'G', changed all the 'E' notes to 'G' etc., changed the key center of the music from 'E' to 'G.' Example A.

Thinking in 'movable One' speak, we 'moved' the 'One' note, from 'E' to 'G', and then measured and built the rest of the pitches in the line from our new One, 'G.' So, 'transpose' keys = 'movable One?' Yep :) Works for any of the 12 keys ? That any of the 12 keys can be 'One?' Yep, that's the magic of 'movable One.' And Bach had this too ? Yep. Coltrane 200 years later ? Yep. Yep, Bach, Coltrane, U and me and everyone in between, and times way before even and still today :) So do learn it here and rote it up if needed and join the now global collective consciousness of the 'movable One.' |

Review and quiz. We use a key center with its own unique set of pitches to organize a song for performance. Very common on the bandstand to add ... 'in what key', into what the band is going to play next. Once the key is known, and we mix in a style and groove, we probably have enough to get started. |

While most songs come with a key, a most common way to pick a song to perform is to suggest a 'form for a song and a key center. "How about a 'blues in 'A ?' Is a quite common suggestion on an Americana bandstand. That it is a' blues' means that it'll probably have a 12 bar form. In 'A' means that 'A7' is our tonic chord. If it turns out to be in 'A' minor, you'll hear it on the first chord. How it all counts off determines how it goes, figure the rest out as we go, and meet ya at the coda :) |

We think of key centers and their unique key signature to help write a song down in music notation, which really is just a paper road map for the song. Other players can then recreate this song from its map. Our standard notation of today, roughly 1000 years old with various evolutions, is the written paper 'recording' of the song to pass along to friends, colleagues, future generations of artists. Thanks to equal temper tuning, we get twelve equally unique and independent letter named pitches. And while we can expand this number by adding another octave or two, the basic theory of the 12 letter names always remains the same.

|

"Leap ... and the net will open." |

wiki ~ Charlotte Fox |

References. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

Find a mentor / e-book / academia Alaska. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music and can help you with your studies in the musical arts. |

|

Always keep in mind that all along life's journey there will be folks to help us and also folks we can help ... for we are not in this endeavor alone :) The now ancient natural truth is that we each are responsible for our own education. Positive answer this always 'to live by' question; 'who is responsible for your education ... ? |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

~ |