~ soloing through chord changes ~ ~ the 'rule' of hearing the changes in the line ~ ~ root to root and the bass line stories ~ |

In a nutshell. In creating theory discussions about Americana improv here in UYM / EMG, making the general distinction of improvising 'over or through' the chord changes of the song can simplify the learning. While we often combine the two in when making music, musical style usually determines between which of the two approaches is generally used. Towards the diatonic, folk side of our spectrum, we're usually thinking more 'over the changes.' |

And on the jazz horizon, and if you're looking to 'jazz up' your licks, almost by necessity of its advanced color tone harmonies and common use of modulation, we're thinking of improvising 'through the changes.' For there are generally just too many non-diatonic pitches in the written chord symbols to apply one diatonic scale over a song's chord progression. Not that it can't be done but there's just a lot of nuanced coolness with non-diatonic tones that we can discover by creating ideas that move 'through' the changes; using chord tones and arpeggios |

'Think from the root of the chord and you'll never get lost.' |

Root to root. Soloing through chord changes opens our artistic senses with just a wee bit of understanding of the structural theory of our musics; to spell out the letter names of the pitches of the chords of a song and string these pitches together over the song's form. Isn't this what bass players do in their walking bass lines? Yep. |

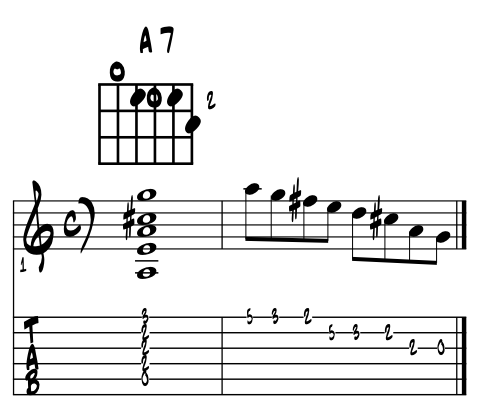

Practice through the changes. Easy do as they often say up North, just play any chord and use its shape of pitches to create a melody line. Example 0. Chord shape, scale shape, push the buttons, that's the easy part ! Now, our job as artists is too use this group of pitches, chord shape based, to create a melodic idea, in the context of the song we find it. Start 'through the changes' simply by going shape by shape through any song's chord progression, U'll be amazed how quickly it seeps in and how a chord shape yields up melody ideas. |

Historical overview and a new way forward. In October 1939, jazz saxophonist Coleman Hawkins recorded "Body and Soul", a pop song of that era. And in his version, once the melody is stated in the first 8 bar 'A' section, Mr. Hawkins improvs the rest of the three minute track by improvising with arpeggios through the written chords of the song. Two full choruses complete the take. This created a new way of improvising, using the chords of a song, and their arpeggios, to outline an improvised melody that fits right with the harmony, just as jazzing up the written melody had done all along. Combined, the improvisor's palette goes kaboom. And this is the resource we improvising artists can inherit today. |

|

Once this recording hit the shops and airwaves, players further considered the 'storyline' aspect of the composition and realized that the chord changes of the songs they were performing could provide a new framework for their improvised melodies. Things as they say ... 'haven't been the same since.' Within a few short years the 'race through the changes' was on and Bebop, among America's most advancing and difficult of the jazz arts, becomes the 'new thing' over the 1940's airwaves. |

'Through the changes.' In improvising through the chord changes, we want to be able to hear the supporting chords in the single note melody lines we create. Many of our improvising instruments, such as the horns, cannot play chords like we guitarists can, so they rely on a solid reflection of a chord's pitches in the single notes they string together to create their improvisations. |

The idea of 'through the changes' simply means we'll look at each chord as it comes along and see if there's not something a bit extra and unique in addition to its diatonic function within a key center of the song. A pitch or two that will better define the harmony of the moment that we can turn into something cool in our single note lines. |

The core skill to thoroughly master here is to spell out the letter name pitches of the chords in the music you create. These we use to play 'correctly' through the chord. Termed an arpeggio, once the theory process is in place to spell our chords, we simply pay some dues and rote learn what we need. In doing so we create a solid resource to improv through the changes using arpeggios. |

Combining both. Most of the improv we hear in any style really is a combination of these two approaches. For while great melodies have come from both ways exclusively, in a combined approach we simply get the best of both; a more horizontal scale shaped line with the more vertical shaped of the arpeggiated chords. |

Once hip to the ideas in these discussions, start to take apart your own favorite melodies and don't be surprised if you find a combination of a scaler, linear shaped lines sounded 'over the changes' with intervals or arpeggios that take us exactly through the spelled out pitches of a supporting chord. Understanding and using the best of both together, so as to hear the changes in our improvised lines is our long term goal, one that will ever continue to evolve for those so inclined. |

A rule of thumb; 'think from the root and never get lost.' The basis of through the changes is to think from the root pitch of whatever is happening harmonically at that point in the music. This works for both pathways. In creating lines 'over' the changes with a pentatonic and or diatonic color, the root pitch we're thinking from is usually the key of the music. |

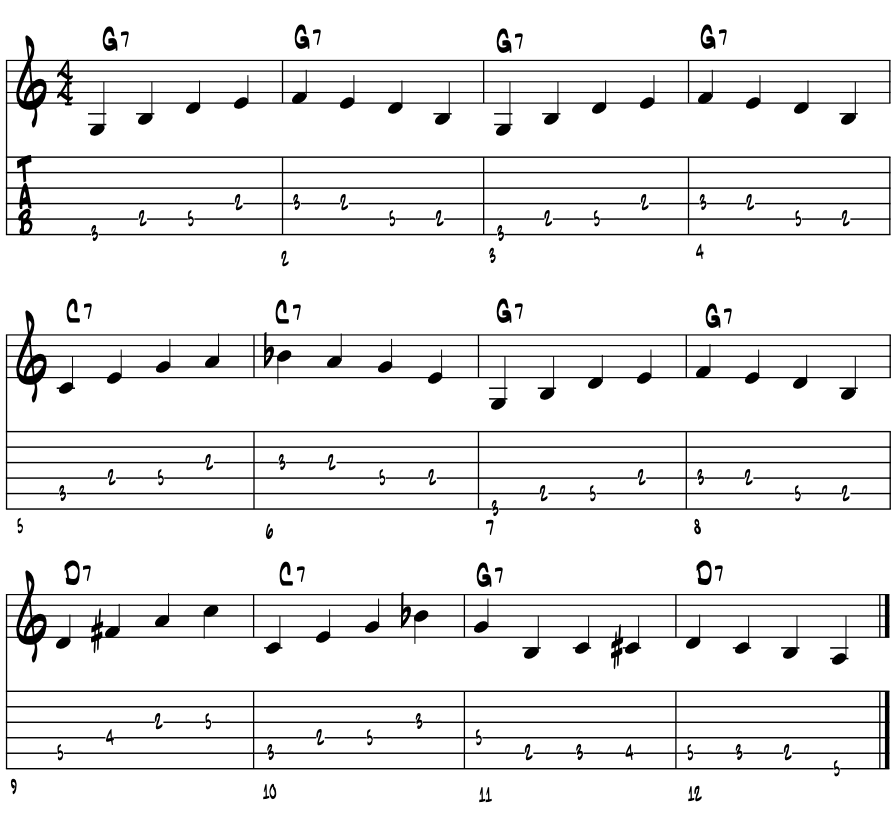

In improvising 'through' the changes, depending mostly on style, each new chord can present us with a new root pitch; which when all strung together creates the bass line for chord progression of the song. For example, in early rock n' roll 12 bar blues form tunes each of the three principle chords are arpeggiated in turn; we're playing through these chord changes Amigos :) |

Arpeggios rule the day. If needed, learn this lick here and rote learn it in a couple of keys. It's the basis for some boogie woogie piano (left hand) and just a classical Americana bass line. For up and coming cats looking to gig, you'll get some pro mileage out of this arpeggiated, through the changes line. Its '1 3 5 7' core becomes the basis for tons more lines and it shares well with others in the band. Thinking 12 bar blues in G. Example 1a. |

|

|

Again sorry but do learn this lick right here if you don't yet know it. For up and coming cats looking to gig, you'll get some mileage out of this, for it's the basis for tons more and it shares well with like minded others. Add the 'Muddy' walkdown and there's a lot you can potentially play on. Got the main blues 'box' scale under you fingers? Can you move it into position for the One, Four and Five chords? Tis an easy path in to getting started improvising, one that so many have traveled along. |

Quick review. That 'through the changes' improv is based on spelling the pitches of the supporting chords, let's pause a moment and go through the spelling process. Basically we need all seven pitches of the diatonic scale to create the basics of functional harmony for improvising through the changes. The links to the right outline the basic evolutions into a fully functioning key center so to speak. Click off to explore if you see something of interest to review. Continue here for the basics of spelling our chords. |

|

A parent scale evolves. We start the process by deciding the key of the music. 'C' major is our initial choice as we've no accidentals applied to the pitches. Please examine the chart for the pitches of 'C' major through one octave. Example 1. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

Evolving a scale into its arpeggio. The next step in spelling is to turn our stepwise scale pitches into its arpeggio. First we expand our scale into a full two octave span by simply skipping every other note and working our way through all of its pitches. This creates our chord tones. Example 2. |

|

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

The arpeggio. The arpeggio is the 'chord scale' used by any instrument when they want to sound out the pitches of the chords in a song. As guitarists (and for piano players too) we can do both; sound out the arpeggios in succession to hear a chord or, stack up the pitches and sound them together as a chord. Here is the arpeggio and chord from the first scale degree of 'C.' Example 2a. |

|

And that's the theory. In this last example we get the basics of soloing through a chord change. We sounded out the arpeggio pitches and then stacked them up and sounded them together as a chord. And three notes makes a triad yes? Exactly. We're spelling the triads on each of the seven scale degrees of a key center. To triads we add color tones and extend the arpeggios. Everything else we'll do here will follow along these basic theory guidelines. Too easy? Then rote learn all the changes through the 12 keys :) So in theory yes but in practice ... and depending and on circumstances, a wonderful challenge and then something more to make it art :) |

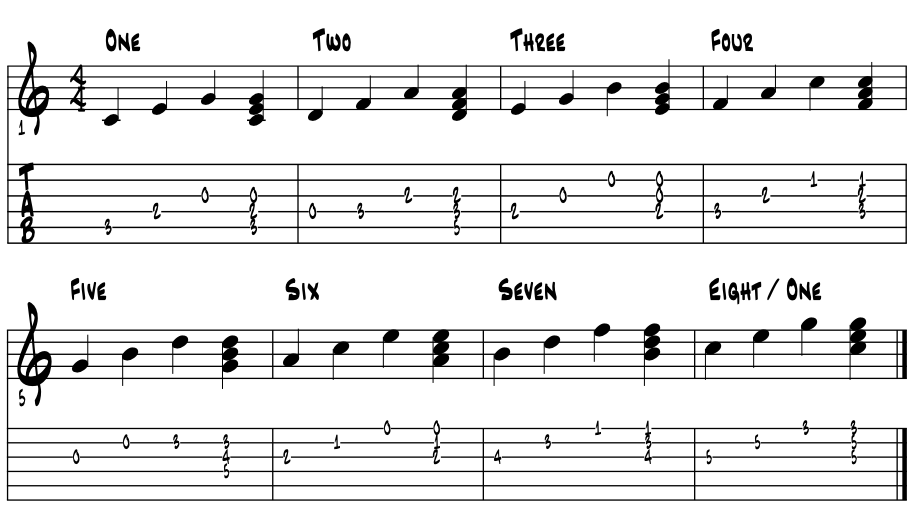

A chord on each scale degree. As most songs use a couple of chords or more to support the melody, in getting our arms around all this we can expand our chart to spell out the seven diatonic chords of any given key center; we simply build a unique chord on each scale degree. These become the diatonic chords of our song's chord progression. This provides the gist of the chords for most of our music. Please examine the letter names and sounds of our seven diatonic triads, One through Seven, in C major. Example 3. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

One |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Two |

D |

F |

A |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Three |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four |

F |

A |

C |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Five |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Six |

A |

C |

E |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Seven |

B |

D |

F |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

It is from these seven triads that we make up our chord progressions. Depending on the style of music we're working in, we'll do any number of different things to best support our melody and create variety. These often include; adding the 7th, adding additional color tones, creating inversions of the triads, finding melodic ideas, arpeggios and chords that live in between these seven diatonic positions through chord substitution. |

Hear the changes in the line. In this next idea we simply arpeggiate these seven chords in a new sequence. Can you 'hear the changes in the line?' Hint; it doesn't start on the One chord. Example 4. |

|

Able to catch the progression by ear? The progression goes like this; Four, Three, Two, One, Four, Five, Six, Seven, One. Try again if needed. Hearing the changes, melodies, intervals and all of it falls under the academics of 'ear training.' It's a fair amount of the work involved as we develop as music theorists. 'Hearing the theory' of the pitches as a song moves along is a goal many pursue over the course of their careers. |

The long view. Can I convincingly improvise a single note melody that clearly carries the progression of the harmony too? As the harmony evolves through styles and artistic evolutions, our degree of challenge evolves also. Add in brighter tempos and we're right back to busy and up to our elbows with stuff to shed and drive deeper into our rote and muscle memories. Many many love and cherish this unending artistic searching. Again, if there's a beginning secret understanding to unlocking this theory, it is learning how to spell out the letter names of the chords we have in our songs and then them find them on our guitars. |

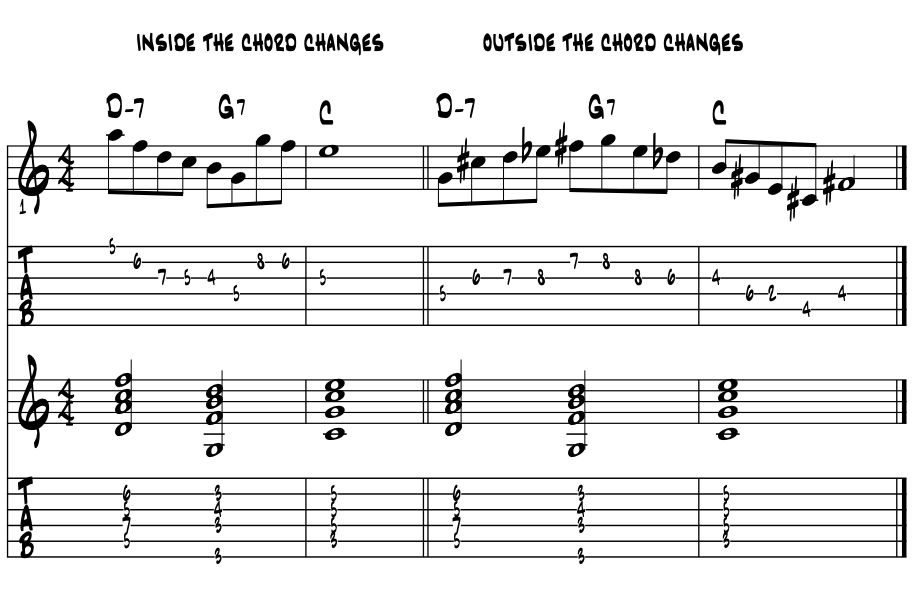

Inside / outside. A further distinction for improvising 'through' the chord changes is commonly termed 'inside and outside.' If we can't hear the chord changes in our improvised melodic lines, there's going to be issues. And when we 'side by side' two improvising artists, one right after another on the same chord progression, with one cat blowing 'inside' and through the changes while the other moves 'outside' of the changes, our emotional reaction to the music often changes dramatically, as the difference is often quite startling in its effect. Compare the two approaches. Two / Five / One in C major, first 'inside' then 'out.' Example 5. |

|

Hear the difference? Concord versus discord? Sounds fine versus what is that noise ? :) Yea pretty much. And while there's surely places for both approaches, if we can evolve through from inside to outside and understand the process along the way, we'll have the best of both. The ability to play over or through the written chords to make harmonious music as well as the ability to 'take it out' of key when our muse or the music calls for crazy, sounds to portray the zaniness of it all. |

|

Any chord can be a riff generator. In our Americana musics, we've two solid choices for creating melodies over chord changes. There's 'over the changes' and 'through the changes', this page's topic. Both these options mix together of course and both are created with changes, or chords, or voicings for piano and chord shapes for guitar. With guitar, we get a sort of puzzle of dots that we can create a lick from. That some of the most classic Americana riffs come straight off the chord shape is no surprise. I first learned of this idea from guitarist Jerry Lavene. |

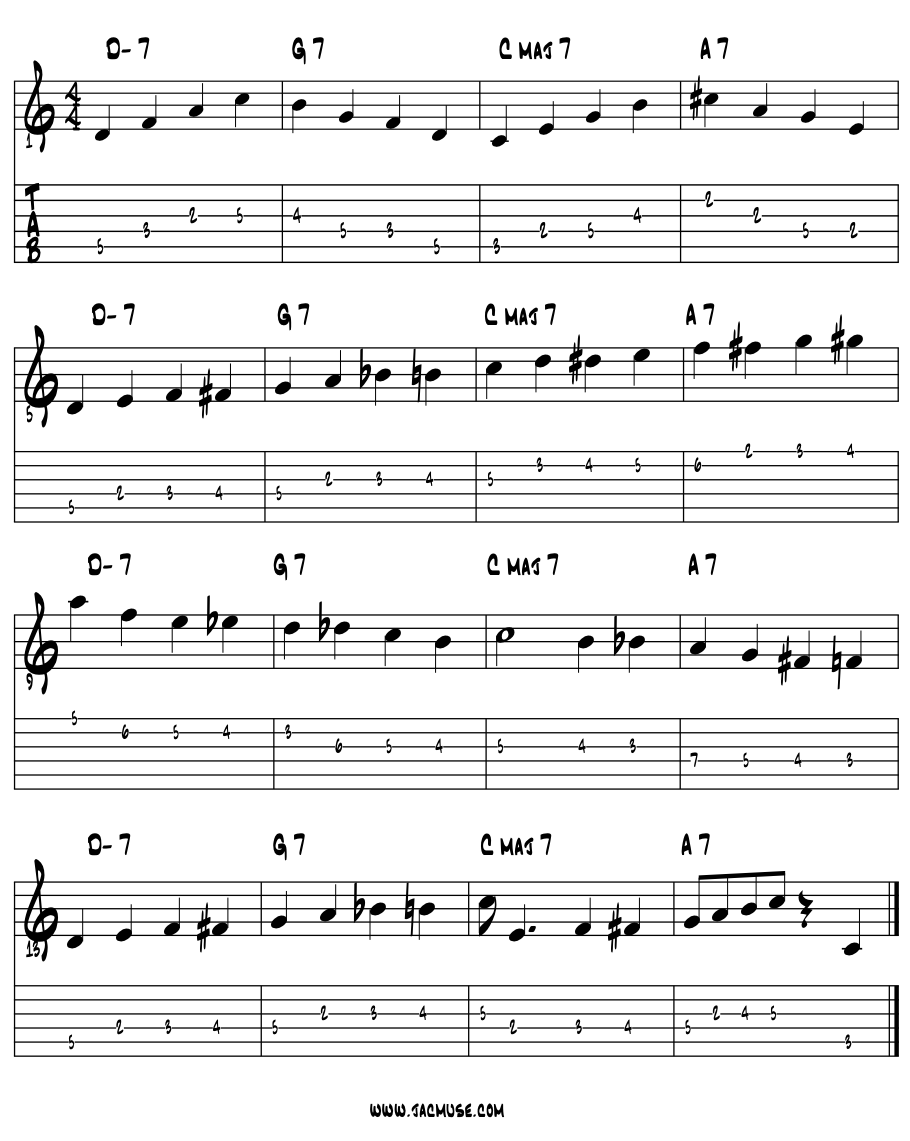

'12.' Another approach to playing through chord changes is to sound out the pitches of the chromatic scale, so all the '12' pitches we get, and play lines in one direction that follow along with the bass line and chords of a song's progression. Using a '2 5 1 6' cycle of chords, arpeggios first then the blurring. Thinking in 'C.' Ex. 6. |

|

Cool ? This probably works best with these cycle of 4th's styled chord progressions, which are the basis of a ton of jazz tunes that swing. Knowing that the 'muddy' walkdown licks have some half steps this'll work in the blues. And is better suited for the shed than on the bandstand. Chromaticised melody lines are the coolest so maybe too easy to have too much of a good thing, but for developing one's ability to 'hear' the changes in their lines its a solid challenge, all of which can be jazzed up at a 'moment's notice :) |

A common start point. Improv in many Americana styles has the blues musics as part of its basis in theory, history and in performance. So we can use the blues and its pitches, chords, form and time to initiate and create a study strengthen this 'through the changes process.' We couple this with gradually adding new chords into the 12 bar form, each new chord needing to be outlined in the single note line. And while this heads us in a jazz direction mostly, it is a good way to begin shedding 'through the changes' for it puts us on familiar ground with a predictable form that creates our own ideas we can use on the bandstand. Find a metronome, getting clicking on 2 and 4 and play through 12 bar blues. Thanks to all our heros over the decades, there's tons of subs to pepper in as the ears evolve and we learn more tunes with more changes. This prescribed process was a shedding essential for jazz guitarist Emily Remler, who subbed out the metronome by using her foot tapping to create the 2 and 4. Not so easy a task as things start to get along :) |

|

Jazz improv. Jazz improv covers the whole tamale of what the Americana musics have to offer. That we've a solid library of audio recordings and video films to enjoy and learn from that spans the range of creativity within the jazz stylings. From a soloing through the changes lens, in jazz we can energize a full exploration of what we can combine of the blues and the harmony that equal temper tuning provides. Combined together we really have the full palette for creating the Americana weave of aural colors. Add in the rhythms of the parade, now 'house', big 4, the 2 and 4 backbeat pulse of the blues and beyond and the '2 feel' of the samba dances, and we've a solid resource to express our ideas. Historically, artist to artist mentoring and with various technologies, listening to music is the way in to all of this palette. With the simple process of repetition and rote learning to internalize the magics, (find one recorded song that totally turns you on and spin it for a month, memorizing each of the parts by your voice). Once there we grow an inner sound vocabulary to express our ideas in our musics. So jazz covers it all huh? It sure can. The whole tamale? Yep, the whole tamale :) |

Even in theory; no limits. Beginning to see yet another 'endless pathway of unlimited exploratory coolness and challenge' for your music with the basics of soloing through chord changes? Cool, we've a few of these unlimited pathways to choose and pursue. Soloing through chord changes opens our artistic senses right up with just a wee bit of understanding of the structural theory of our musics; spell out the letter names of the pitches of the chords of a song and string these pitches together over the song's form. Many great improvisers started out as youngsters playing the melodies included in EMG. They come from the standard text that was used in the public schools during the last century. These melodies capture the Americana spirit we all cherish and strive to fulfill and share. So in learning these melodies, we tie right into our musical DNA. Once under our fingers we gain the color melodic colors for our improvisations. There's also the pathway of dedication to the art and the time put in that all may follow, working to master the art of improvisation through this most basics of basics; sing the line, play the line. And this any of us might do with whatever ideas we come up with. |

“I once heard Ben Webster playing his heart out on a ballad,” he said. “All of a sudden he stopped. I asked him, ‘Why did you stop, Ben?’ He said, ‘I forgot the lyrics.’ |

wiki ~ Ahmad Jahmal |

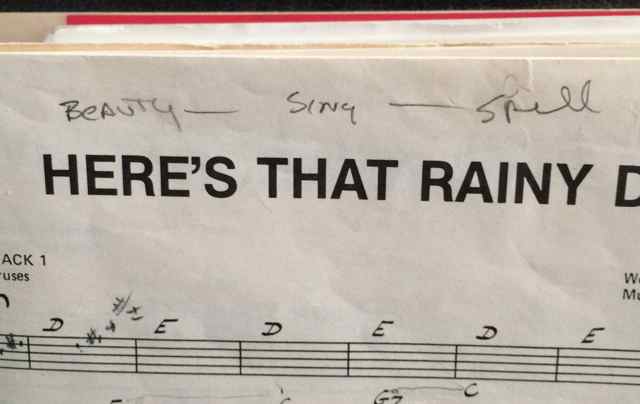

Handed down to us. The following picture is taken off the music stand of a good pal here in Alaska Eli Whitney. Early on in his career Eli had the opportunity to take lessons with Jackie McLean, who in his early days had spent time with many of bebop's finest including arpeggio king Charlie Parker, whom he subbed for on occasion. During a lesson he described his process of 'reading through the changes' as a way to improvise and spoke of how this was a common approach for many players of his generation and circle of musical friends. The penciled in words at the top of this chart are written in Mr. McLean's own hand. Sums it all right up nice :) |

|

|

Review. Soloing through chord changes gives us an opportunity to improvise single note melody lines that aurally captures the emotional character and direction of the chords of a song. For most our styles; folk on through to pop, we're in a diatonic environment. And if we use the correct associated pentatonic group, we're really forever golden. Our responsibility mainly to find the melody of the song, riff on it and conjure up some mojo to get it all going on as a soloist leading the group. |

For as my buddy Stu once remarked, 'in the songs I play there's really only a couple of choices where the chords can go Joe.' This in reference to his soloing in mostly diatonically created musics; country swing, the blues and rock stylings. Soloing over the changes. Even so, when listening to Stu working the magic, chances are good he'll somehow nick 'extra' pitches along the way, an opportunity to expand by working 'through the change.' |

Through the changes becomes more of a necessity in jazz for tempos accelerate, there are more chords altered from their diatonic basis, there are chord cycles within progressions diatonic to other keys and the complete changing keys or modulation is very very common. In these sorts of challenges, arpeggiating a chord's pitches wins the day to hear the chords in our improvised melodic lines. The theory basis of this is developing the ability to spell any chord in relation to its own key center and its parent scale or mode. |

The eventual rote memorization of these components and fingerboard shapes gradually become assimilated through shedding. We theorists can explore the idea of 'chord type', which allows us to create three 'categories of chords' that facilitate the learning process. That any chord in our lexicon can be one of three 'types' can truly reduce the amount of shedding dramatically. |

Here in Essentials, learning melodies is the key to our improv as we can discover all of our music theory in an already completed artistic form. We can extract any bit of melody coolness and run it through near endless theory sequences or 'filters' that potentially expand any motif into complete works of art. That in listening to accomplished soloists we often hear just that; a continuous stream of melody created from bits and pieces of other written melodies. This is also one part of the reasoning that encourages jazz artists to learn songs in a couple of keys, if not all twelve, creating a 'database' of ideas or as termed in the old days, a 'bag of licks.' |

The blues can be a sure fire way into developing strength for soloing through the changes for the evolving guitarist. With its solid 12 bar form and three four bar phrases, over the last century or so nearly every nook and cranny has been explored. Thus today we inherit a solid library of chord substitutions that make good sense when located within the form. Once a chord substitution is established in the blues, we'll find other working spots for these ideas in other forms, songs and styles of music. |

"It always seems impossible until it's done." |

wiki ~ Nelson Mandela |

References. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

Find a mentor / e-book / academia Alaska. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music and can help you with your studies in the musical arts. |

|

Always keep in mind that all along life's journey there will be folks to help us and also folks we can help ... for we are not in this endeavor alone :) The now ancient natural truth is that we each are responsible for our own education. Positive answer this always 'to live by' question; 'who is responsible for your education ... ? |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|