|

~ Bach & Coltrane ~

|

||||

|

~ |

|

||

In a nutshell. Arpeggio kings Bach and Coltrane are the theory explorers and historical composer bookends of the music theories in this work. While our studies here do go further back in time than Bach's, which centers around 1725, and ahead in time after Coltrane's sojourn, in 1960 with "Giant Steps", understanding the theories of our Amer Afro Euro Latin wonderful cultural weave of today is clear; as Bach provides us in written record a thorough guide to what our original gospel harmonies and chord progressions will become, while Coltrane advances these foundations by developing a new pitch relationship between harmony and melody through a modern cycle of chords, done while improvising and shared to us aurally. |

J.S. Bach. For beginning around the 1550's or so, word got around Europe that the solution for tuning up the pitches to equal temper exactitude was now becoming possible. In 1700, Christofori crafted a mechanism for regulating the dynamics of 'loud and soft' for each of a piano's keys, by the strength of touch of a finger. By 1725, super keyboard wizard Herr Bach had a version of this new magical 'piano forte' instrument under his fingers, and had completed his first edition of his "Well Tempered Clavier." The first song in this folio is the one analyzed in the following discourse. |

|

By the early 1740's, Bach has completed a second addition. These two folios provide a very clear snapshot of the 'Euro' stylings that were coming to the America's. Bach is gone to us by 1750, but in these two volumes, written near 20 years apart, is a sort of sum total of what we Americanos will eventually inherit and then use to harmonize support for our own 'spirituals' of this era, stories told with voices, with rhythm and melodies. Combined, 'Euro' Bach piano harmonies and 'Afro' voice melodies becomes our own Americana 'gospel.' It takes another 200 years to fully 'Amer Afro Euro Latin'-ize all of the chords and keys that Herr Bach laid down, but by the 1940's, the Bebopper's surely did, in tempos that in all probability Bach would have thoroughly dug too :) This is the harmonic palette we have today. |

John Coltrane. In 1950, saxophonist Coltrane is 25 years old, and by the close of the coming decade, has become 'the rising voice' in NYC jazz. Through a decade of diligent study, and using arpeggios to represent chords, by 1960 Coltrane has evolved our harmonic inheritance from Bach, now filtered through bebop too, creating jazz's next 'giant step' forward. Focusing on harmony and following the traditions of 'soloing through chord changes', Coltrane reworks common chord progressions into a new cycle with a modern application of the ancient pentatonic colors, all at blistering tempos. These achievements revolutionized jazz, and marked the beginning of a new era for Americana musics. And as with our theory studies of Bach, we can discover Coltrane's harmonic evolutions as written into his original songs. By following the release dates of their recording, we're able to create a rather clear and theory defined step by step academic theory evolution of the resources, a pathway that creates a study guide for a BA level of harmonic / melodic theory studies and performance for aspiring jazz leaning artists. And by examining the melody pitches and harmonic scheme of these four compositions and a bit beyond, we can discover Coltrane's pioneering evolutions; a weaving of a blues / gospel core right on through to a completely modern 12 tone Americana tonality. |

While inventing new cycles of modern harmony of an unparalleled strength, Coltrane consistently retains the blue's hue in gospel and swing rhythms, those two qualities that have always made our musics Americana, that reign on still today. Once the new harmony was settled, Coltrane pioneers a new way forward in melodic improvisation by approaching the now ancient pentatonic colors in a startling new way. Gone to us by 1967, Coltrane's musical art establishes a 'new school of music', for both his dedicated work ethic and the evolutionary pathway to "Giant Steps" becoming a curriculum of study that today is found on dedicated music college campuses around the world. |

So in our theory studies here, Bach and Coltrane become our harmony bookends. History tells us that both did the shedding, and made their understandings of harmony and its possibilities presented clearly in the music they wrote. That both looked to 'exhaust' the available pitch resources of their respective times is a testament to their dedication and creative forces. Super thanks to folks all along our historical way, that we today can explore the magics of these musical masters in sound and in the print of what we hear. Combined together, we've got what's needed to analyze the music and discover the artistic ways of these masters. |

Taken together, my work attempts to weave a combined historical, theoretical and cultural time line through understanding our music's harmony's evolutions and tonal qualities from an inside, diatonic basis and on through to the distant realms of outside the diatonic realm, the polytonality, atonality and eventually the full 12 tone chromaticism of free jazz and beyond. |

|

That we have publishing dates and scores for both of our composers helps this study scheme. Artistically is where the real challenge begins, as we each must decide for the creation of our own current work, which elements along this 'inside / outside ~ tonal spectrum' are necessary to bring forth our own art. Then the shedding begins to master the chosen resources; the pitches into parent scales and their evolutions into arpeggios and chords. |

arpeggio kings |

~ 1939 ~ "Music should always be an adventure." |

Coleman Hawkins

|

Arpeggio jazz kings. In our Americana history it turns out that there's three jazz artists whose use of the arpeggio figure in their improvisations became a catalyst to change the music of their day. And in doing so provided a base to build up on for what would come after. These three are honored here as the 'arpeggio kings.' Historically in order, first is Coleman Hawkins, then Charlie Parker and then John Coltrane. |

|

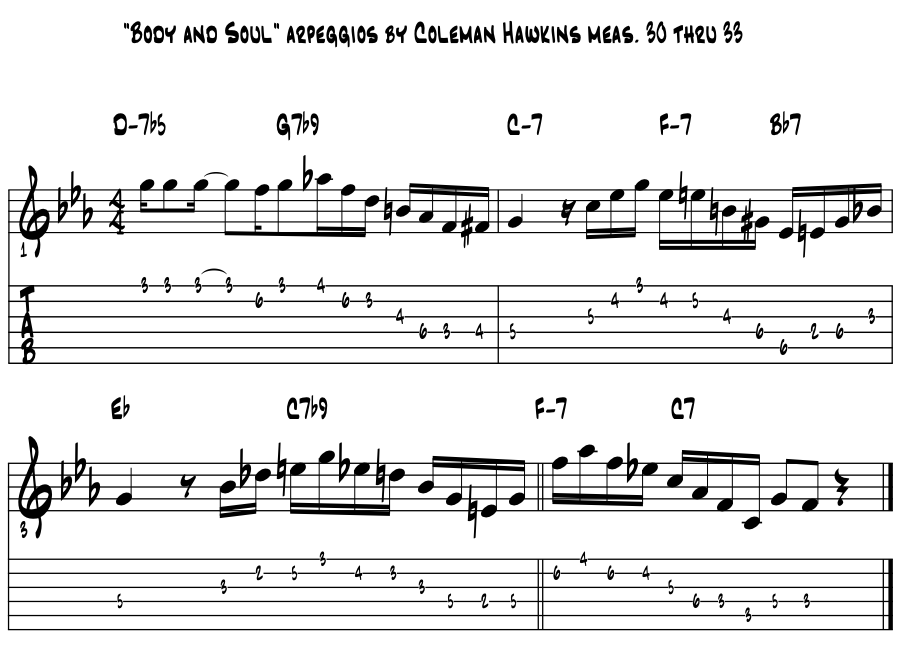

Coleman Hawkins. Our beginning point becomes 1939 in NYC, when Hawkins' recorded the popular song of the day "Body And Soul" as an instrumental on tenor saxophone. For in his recording, Hawkins' arpeggiates nearly all the changes in the tune. There's bits of the melody, some very cool bluesy turns, but the single note melody of the horn line is 90% arpeggio pitches, created from each chord as the song's progression moves along. No artist had ever done this before, created an almost pure arpeggiated approach to the changes, and not worry too much about the melody, just super clear outline the harmony by creating an 'arpeggio melody line' from the pitches of each chord. 'Spell the chords.' And once the sound of this got around, and historically from this point forward, the changes become enough of a stimulus and backing for creating single note line lines. And for single line instrument players, this means articulating accurate arpeggios of each chord and its color tones. Example 6. |

|

|

This 'outlining each chord with the pitches of its arpeggio, presented to rhythmically swing with the band, becomes a model of modernization of improvisation; that the form of a song and its harmonic progressions can form a soloist's basis for blowing. |

arpeggio king |

~ 1947 ~ "Learn your horn and then forget it and play jazz."

|

Charlie Parker. In our Americana history and its evolutions, Mr. Parker's musical genius lives between Bach and Coltrane. For Herr Bach, in the 1720's, begins to show us the harmony potential of the then newly adopted 'equal temper tuning, of what's diatonically available, with the 12 equal temper tuned pitches, in the Baroque stylings of his day. And thanks to his two volume "Well Tempered Clavier" of 1722 and 1741, we get a quite a thorough going over of the 12 paired key centers. |

|

Parker's genius comes historically about a decade or so before Coltrane's evolutions. In a similar fashion to Bach, Parker conquers near every nook and cranny of the diatonic realm, of Americana melody and harmony in the coolest styles of his day generally called bebop, all of which is written into his fifty five compositions and improvisations of the Charlie Parker Omnibook. |

Parker shows how each of the 12 pitch positions of the chromatic scale are now available, to create some sort of chord, both diatonic and passing, thus providing a basis and support for a melodic line. Each chord's pitches anchor his melodic lines. Deftly woven into purely joyous Americana songs with freely swinging rhythms at any tempo, Parker's compositions retain the 'diatonic' of his era yet still 'nick' pure blues and gospel somewhere along the way, of near every phrase that comes along. |

Parker's ever present bluesy, gospel Americana flavored melodic line, and often working this through the fastest tempos every attempted, sets the bar for Coltrane to better, to search deeper into these initial '12 tones within the diatonic positions' and what the theory can generate in the tonal convergence of modern musical art. |

From art, its theory. In Parker's early years as a pro, the popular music that surrounded him in the late 30's knew of Hawkin's arpeggiated approach to creating improvised art and cats were doing it. Parker simply builds on this basis but to an exponential degree that folks had never heard before. Ridiculed at first, trying out his new idea still yet not fully formed, Parker goes on to solve this problem by playing everything 'necessary' in theory, to make his licks work. For like Hawkin's, Parker arpeggiates most every chord in a song's progression, then while that harmony is still in play, jazzing it up with his own signature sound and ideas. Add in brighter tempos that swing deep and we come to the bebop style, Americana's most complex ever created. Theory termed to 'hear the changes in the line', 'if it ain't a blues lick', then Parker will include every note needed to clearly hear 'the chord changes' in his improvised lines. |

|

Mr. Parker fully expressed this technique through the chromatic magics of '12 tone equal temper Euro pitch potential' of our own indigenous Amer Afro Euro Latin jazz. Lest we ever forget that this jazz was at one time our collective 'pop' music. As an Americana composer and saxophonist, and 'here too fully crowned as an 'Arpeggio King', Parker and Co., pioneered this new approach to jazz in the early 40's. Mostly termed 'bebop' now by historians, 'bop' was both the most difficult music to play and the most exciting improvised music NYC had ever heard since ... :) |

|

Mr. Parker was said to have also heard pianist Art Tatum perform. Enough so that over a year or so of his own diligent practice, Parker deftly applied what Tatum was doing in his right hand to the whole range of his alto saxophone. To make sense of it all, Parker uses arpeggios, from the root up through all its color tones, to ensure that the changes are heard in his lines. |

|

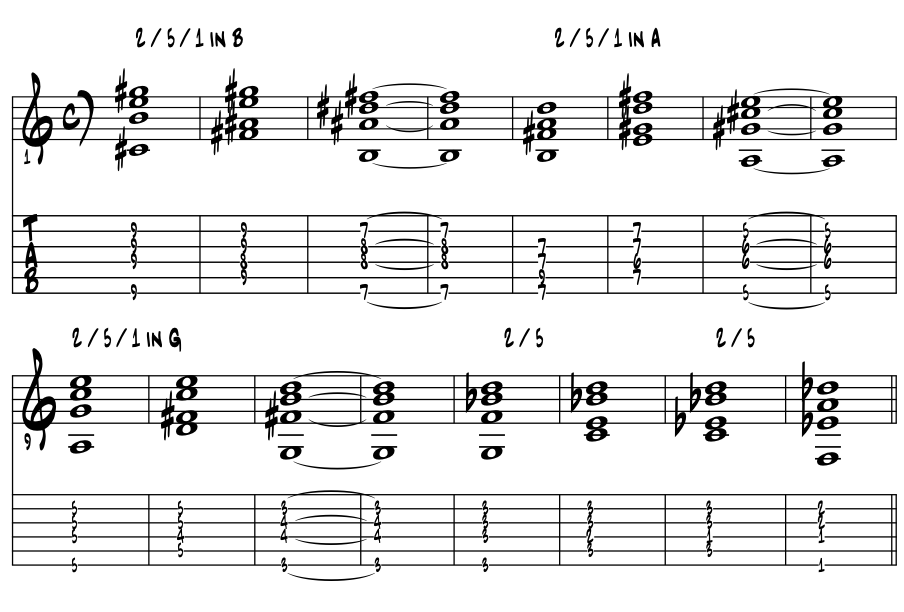

"Cherokee." According to legend, the jazz standard song titled "Cherokee" becomes Mr. Parker's initial portal into the evolution of our harmony and resulting melodic lines. Some say it was in the bridge, with its fast moving modulations with subtle half note melody pitches within Two / Five / One progressions, that Parker's epiphany occurred; five key centers either landed to or implied, through 13 chords over 16 bars. |

|

|

For legend has it that Mr. Parker, then in his early 20's, was warming up prior to a performance by 'running the changes' of this 1938 classy Ray Noble jazz burner, "Cherokee." And that it was in this 'moment' that things 'clicked' and Parker's new vision appears and begins to take shape. |

|

In theory, Mr. Parker simply realized that to play the 'new ideas' he was hearing, he would first have to fully arpeggiate the supporting chord tones to make all of the pitches in his improvised melodic lines 'sound correct.' As the chord progressions of his songs gradually 'filled in' with more diatonic and passing chords, cadential motions and chord substitutions, Parker, through articulating arpeggios, redefined the music of his day as he stayed perfectly 'inside' the changes, regardless of their complexity, and always kept some gospel feel and blue colors close at hand. In doing so, Parker leads us on a pathway to a new apex of our Americana jazz during the 1940's and forward into the 50's. |

|

"Cherokee's" written melody note rhythms are mostly whole and half notes, which gives the artist 'time to think', however briefly, as the music scoots along. For there's a neat trick in up tempo songs; that by sounding a long note value in time through changes, we give our imaginations time to momentarily reflect, to 'suggest' other notes and ideas, which we then try to play. |

We get to rhythmically 'push off' from a bar line, floating a sustained note, create some space. Have time for a breath, and give our minds a window to conjure the next phrase. This 'push off process' works like a charm, and not just in jazz music. Phrasing is the term we musicians use that can describe this two way process. |

This 'long note' improv idea is explained in the book Forward Motion by jazz pianist Hal Garper. Mr. Garper tells us that he learned it from Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet virtuoso, bebop and Latin pioneer who stood elbow to elbow with Mr. Parker. |

|

A synopsis of this work is included at the close of the discussion of musical time included in this book. It creates a way into Mr. Garper's idea of where a phrase begins and ends, which in his discoveries ties us right back up to J.S. Bach, whose experiments with the 'new' temperament of the day helped to usher in the then 'new' era of stacking up pitches into chords. That far back huh? Yep, way back to 1725 or so :) |

"Success softens the mind." |

anonymous

|

Review. Bach and Coltrane are the explorers and historical bookends of this work. For beginning around the 1550's or so, word got around Europe that the math solution for tuning up the pitches to equal temper exactitude was now becoming possible. In 1700, Christofori crafted a mechanism for regulating the dynamics of 'loud and soft' for each of a piano's keys, by the strength of touch of a finger. And we know that by 1725 or so, Bach probably had a piano forte' instrument under his fingers. Meaning? Just that we modern scholars of today can zero right in with Bach and know the basis of the full spectrum richness of the 'modern harmony' we Americanos inherit from our Euro brethren. |

|

||||||||||||

"Be kind, be brave, be thankful." |

Alaskan ~ Heather Lende

|

References. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

Find a mentor / e-book / academia Alaska. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music and can help you with your studies in the musical arts. |

|

Always keep in mind that all along life's journey there will be folks to help us and also folks we can help ... for we are not in this endeavor alone :) The now ancient natural truth is that we each are responsible for our own education. Positive answer this always 'to live by' question; 'who is responsible for your education ... ? |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|