|

|

~ start music theory school ~ ~ just the nuts and bolts of it, well mostly :) ~ the seven musical alphabet letters ~ 'energize your own learning in life through education, exploration and discovery ...' comments or questions ...? |

"A word to the wise is sufficient." |

In a nutshell. Simply to start learning about music. And once under way, lots of ways to explore then manifest. All along the way here we make musical vocabulary words and their meanings into links to further pathways, discussions of similar elements. While we've a few 'start' pages to choose from, this one sums up the whole tamale. This 'start / start' page is for the theory basics. |

So based on your curiosities and what you need to create your musics, begin to create your own learning pathway forward by choosing links or just follow this page's discussion ( or any page's discussion for that matter ) from the top to the bottom, for an academic progression of ideas about any given topic. And be sure to stop along the way when necessary to rote learn the your own basics. And if we wander too far, get lost ... there's always that 'e' book magic in the browser's back button for ... :) |

"Not all those who wander are lost." |

wiki ~ Tolkien |

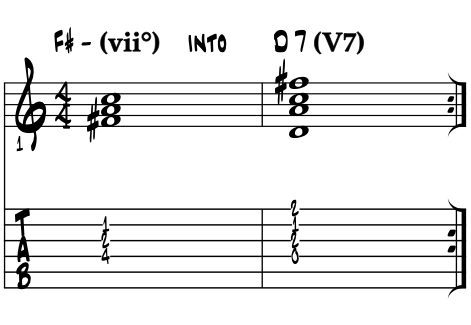

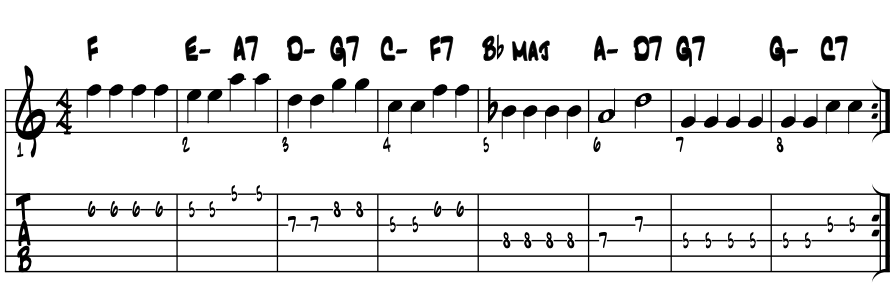

Home ~ away ~ home. I learned this a couple of decades ago now at an elementary school I was visiting. The teacher had a song about our own feelings of our 'home', sounded out by a 'C' major chord. A 'G7' chord was next, representing our travels 'away' from our home, to which we return. Sequenced thus, a true core of all music is revealed. Example 1. |

Ah, the adventures of venturing forth, followed by sense of arrival back, in musical sounds. A starting point for all departures in understanding our musics. Musicians in the know surely know that wherever we go, we will always have a home within our own hearts with our musics. And that the more we can share our music with others, the more global our 'home' can be :) That everything 'loops' helps win the day. |

Nut in shell / phrasing. That we have the components to speak and write words to express emotion, in music, we have the same range of emotional expression with the sounds of music. And like our expressions in letters and words, in our notes and phrases we can convey any thought, any stream of emotions, any sort of nuance. We just need to consciously remember to do it and also of course, figure out how :) That once pitches are physically under the fingers, the the 'art of phrasing' evolves. A super conscious effort to connect the dots between our heart ~ head ~ hands, one pitch at a time and forward. Sing the pitch in all its emotion, find that expressive on your git. Sing and play. In the Americana musics, we get to complicate this process by 'making up these ideas' as we go along. To improvise. Through practice, we each strengthen this process. So one part of our tasking, if we choose to take up the challenge, is to develop our ability to think and express our emotions in our music while moving through measurable, moving time; improvisation. So while making up the music as it goes along, 'improvising' it as we say, to think of expressing the joy in your heart, some mystery or sadness, a poignant frieze to the longing of begging, to straight up 'happy' right on through to contentment, Luckily, improvisation study is simply both preparation, preparation and preparation. We add a dash of luck and show up to perform with musicians who have also been preparing to improvise. We combine our musical voices to express our emotional, choosing songs, or writing ones if needed, that fit the mood and tells our stories. Pretty simple really. Yet, how you phrase is unique and yours. An artistic signature that only you own. And only you can decide whether to share. When you do your listeners might empathize with your musical voice, and the more they do, the more your musical voice becomes your way into the communities of all peoples. musical phrasing = express our emotions in music :) |

"The only place where success comes before work is in the dictionary." |

wiki ~ Vincent Lombardi |

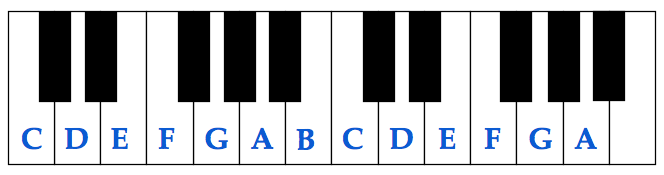

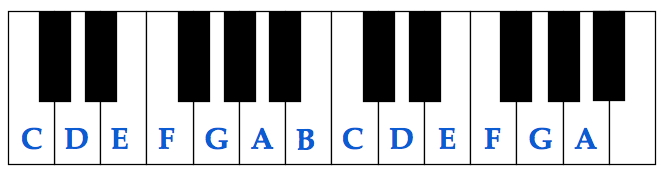

Perfectly closed loops of pitches. This next idea of 'loops' is really an easy way to get our arms completely around our understanding of music. That however we group up the pitches, if we extend its sequencing long enough, we'll always arrive back to our starting letter name pitch. Always? Yep, always. Seems crazy with all of the various musics we've had over the millennia but in theory, this is the law. For example, here's our basic alphabet loop of musical letters to name seven of our pitches. Example 1. A B C D E F G A B C D E ... So just like in our alphabet, when we get to 'Z' we've run out of letters and back to the top we go. In music it is even easier as we only go to 'G', gee. 'A to G', easy :) Recognize these on the piano keys? Example 1a. |

|

How many loops of this 'A to A' do we get at the piano? Measured in octaves (A to A) , as many as seven octaves on many a piano and even modern keyboard instruments. That's a lot of pitches, range and combinations. Oh, and octave? New term? Read on :) |

"Around here, the word discipline is not a bad thing." |

wiki ~ Self Control |

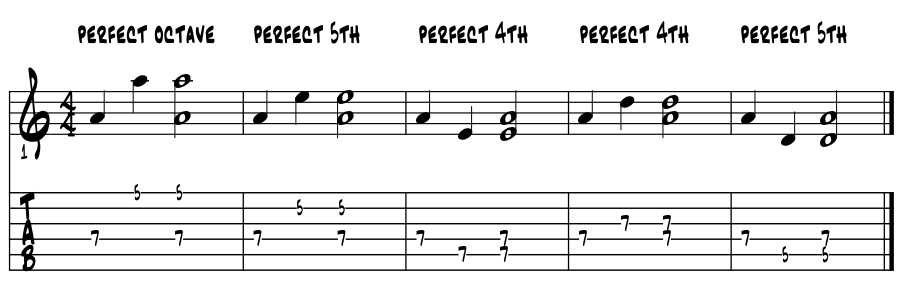

All based on the perfection of sound. In our AmerEuro musics, its architecture is all based on the idea of an 'aural perfection of musical sound.' From this start point of pitch, we create our combinations of two pitches. These notes we can measure, and become our 'perfect' intervals. The idea of an interval is distance, space or measurement of time between two things yes? In our case, we're measuring the distance between musical pitches that we call 'the intervals.' We've three perfect intervals; the octave, perfect 5th and its inverse the perfect 4th. Octaves are the same letter name so no 'inverting' necessary. That an interval up a perfect 5th creates the same letter name pitches as an interval down a perfect 4th. Examine the pitches from our root pitch 'C.' Count the letter names on your fingers, easy. Up a perfect 5th; A up to E; A B C D E. Down a perfect 4th; A down to E; A G F E. Here's the notation. Example 2. |

|

Ever count the lines and spaces on the staff as numbers ? Another first? Right on ! |

Aural perfection. This idea of aural perfection gives us a the basis we build upon. It is determined by how smoothly two pitches aurally meld themselves together. The octave interval is most perfect sounding, thus becomes the basis of our whole theory tamale. For all our 12 pitches will fit within an octave span. While today there's a few ways to scientifically measure this, back in the days when smart folks started up our music theory, they did it all by ear. 'Let your ear be the guide.' |

|

"If it sounds good it is good." |

wiki ~ Duke Ellington |

And the natural half steps. Thinking of the letter name alphabet pitches, we can use the piano to locate the 'built right in' half step intervals of our relative major / natural minor group of pitches. Notice the '2 / 3' occurrence of the black key groupings? Know what interval lives between this sequence? Between 'E' and 'F' and 'B' and 'C?' If you know or guessed the half step, cool. If not just rote learn it right now for it never changes :) Been this way on keyboards for at least a couple of hundred years. Examine a pic of the keys of most any piano we might ever bump into. Example 3. |

|

|

Look familiar? Cool. Find these pitches and run them right to left, so downward in pitch, and find some of your own melodies and motifs to sequence. Or vice versa :) Up from 'C' to ... These pitches are the as 'old as the hills' ones, for near as we might figure for certain. The key of 'C' major and 'A' minor are easy, using just the white keys at the piano, thus no need for any accidentals. Advanced. The black key pitches are for the 'Gb' pentatonic major and 'Eb' pentatonic minor colors. The remaining key centers we'll need the sharps ( # ) and flats ( b ) to place the half steps in their exact spots and work their magic. Confused? Read on and right back to the white keys we go ! |

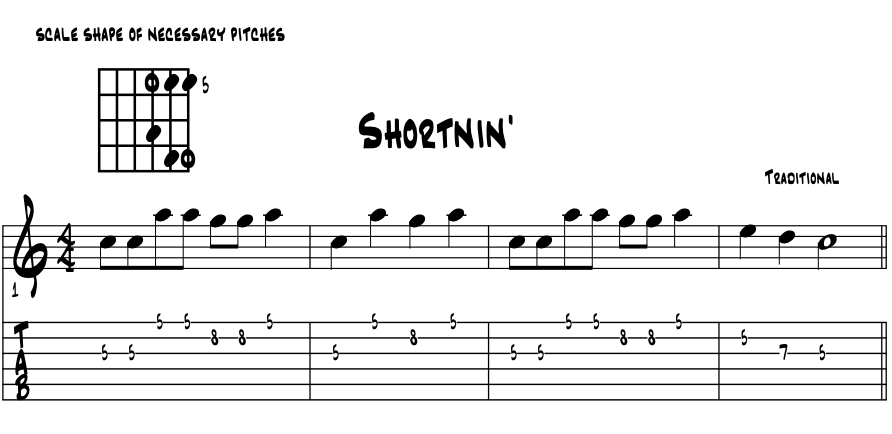

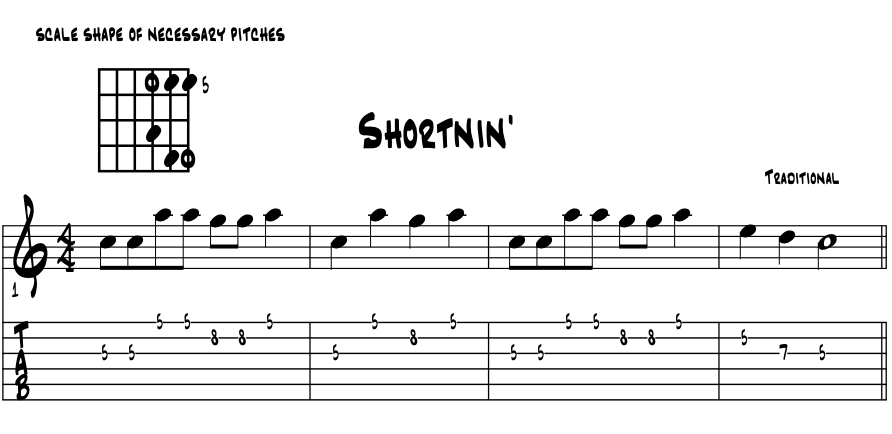

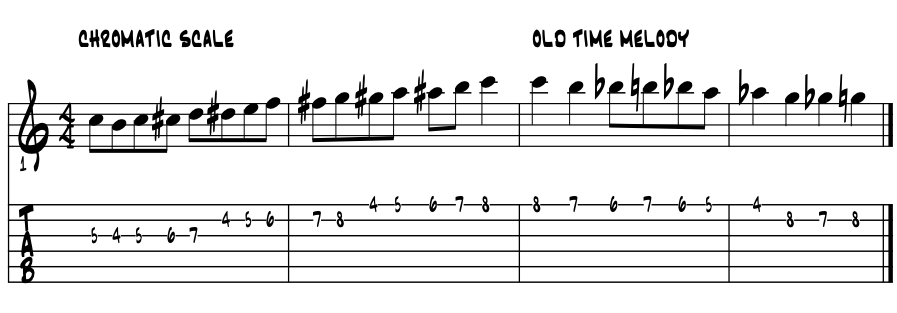

Not reading music notation yet? No worries at all. Start right now :) For in an 'e' cyberbook the written musical examples play back what notation is written. So a solid pairing of notation and playing by ear built right in. Use the string grid and the lower staff tab to help locate the pitches. Know this melody yet ? Example 4. |

|

Recognize the line? Cool. Under the fingers by ear? Does reading help ? Sing and play wins the day :) |

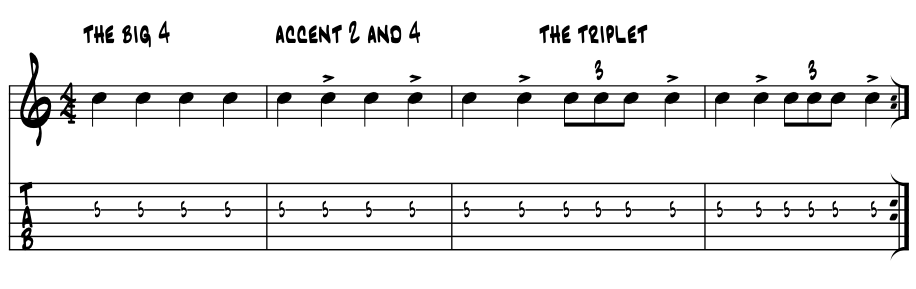

A second way to jump-start improving our reading skills is to begin to clap the rhythms of written music as notated. This helps to train the keep the eye moving, a very key part of the process; keep the eyes moving. With practice, the note symbols become rote. And reading is just like learning most things, just a matter of wanting to do it and teaching ourselves how. Count it off and clap out the following line. Example 4a. |

|

Cool? So a couple of ways into the reading. Huge pile of 'undiscovered' music for those that get familiar enough with a treble clef to sort things out. Why, even just the music written for the flute has got to be a couple of feet high. Its music goes back 500 years ... and so does written guitar music for that matter :) |

So the magic of this book makes our learning here quite modern all around. Knowing the letter names of the lines and spaces of the treble clef staff, the five horizontal lines with a treble clef is an of itself huge knowledge when starting out. Here is the treble staff and letter names. Example 4b. |

|

'G' / treble clef |

treble clef lines and spaces |

||

|

|

Just rote learn the letter names on the staff. Most of the examples in this book are in are in 'C' major / 'A' minor.' These key centers hold the pitches of the white keys on a piano. So no accidentals, no sharps (#) or flats (b). For in writing music that is to be read it is often said that; whatever way to notate our music, that makes it easiest to read, is always a good place to start. Examine the letters of the relative keys 'C major and A natural minor.' Example 4c. |

|

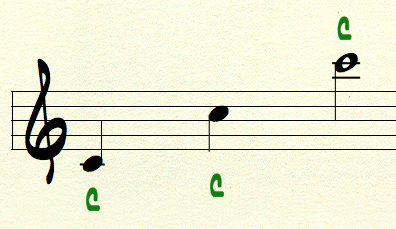

Familiar? Cool. No? Next time near a piano try them out. Not uncommon to push a bit past the staff lines in both directions, to notate the pitches. As 'C' is a main note for our discussions and music in general, here's its expanded notation using ledger lines, just abbreviated lines that follow the loop of letter names for the high and low notes. Example 4d. |

|

|

Quick review. Set in stone theory here? Yep. Global too nowadays. This should get you started on the road to reading. Rote learn the symbols and over time their recognition can and will become second nature. Just work at it and don't quit. Learning to hand clap out the rhythms of written notation is oftentimes the first step in understanding the rhythm part of reading notation. Just do it a bit everyday and it'll happen for you. |

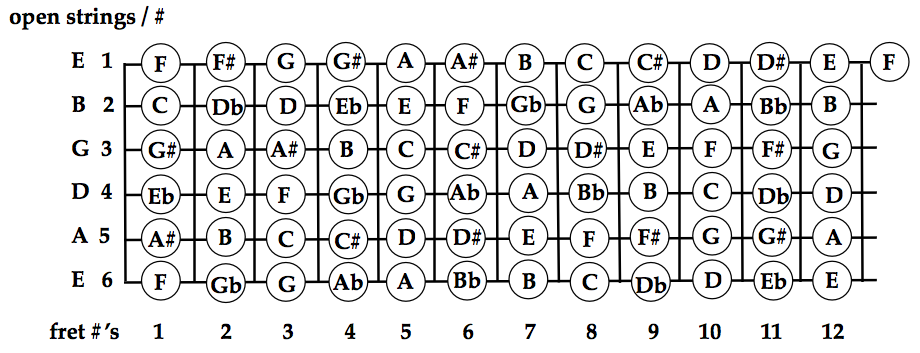

The natural half steps and the chromatic nature of our guitars. So built right into our gits are the half steps throughout. For each fret measures off a half step of the strings to give us the chromatic scale on every string. Examine the following illustration and click on it to hear it some of the chromatic color. Example 3a. |

|

Try and sing along with the pitches. Recognize that bit of melody at the close of the line? |

|

Need to learn the letter names of the pitches? Easy do. Start with the open strings and work it all from there. Ever jumble up their letters? 'E, A, D, G, B, high 'E?' All kinds of coolness with these pitches of course. The open 'G' major triad might be tops, the 'G, B and D' notes. |

And yea, the chromatic color is for wizards. Learning the rest of the pitches takes some work for sure. From the graphic we see that the two outside strings have the same letters. Then just four strings to go. Separated by two octaves, these 1st and 6th string pitches give us the handy reference points. Is knowing the letter names of the pitches akin to knowing the alphabet letters when making words? Yep, sure is. Just begin to rote learn them, even ASAP, and then have them forevermore :) Anything happen special after the 12th fret ? |

Seven steps to Parnassus. This idea goes back to the ancient Greeks, some of whose ideas started on us on this understanding our music journey. Parnassus is a mountain in Greece on who's top a grand tribute is built to the wisdom and intellect of these peoples and their spiritual and philosophical aspirations. The seven steps are the levels of knowledge one ascends to acquire a wide spectrum of wisdom to further build upon. |

And while our understanding of our music is hopefully ever growing and evolving, a sort of puzzle whose pieces can often refit together a number of ways, having a big picture of our resources and organizing systems creates an inner 'thought structure', a personal framework for organizing our knowledge. So as new ideas come along throughout our studies and careers, we can tie it into our existing information, building up our knowledge base for immediate recall when needed. |

For whether you perform, produce, arrange, write and record, or for now just hang with those who do, these skills and their theory should make you a stronger player and contributing asset to your artistic teams. |

The seven steps. Take each in turn, rote learn their basics and take their vocabulary quiz to seal the deal. got a hill to climb ... ah, at the core of it all ... :) |

|

And upon arrival ? And upon reach the pinnacle of Parnassus? To collect a 'rock from the top ... ' as some say ... that we are simply able to play anything we can hear. In music, mine and merry :) Up a half step? Sure. And ... be able to read and write it all out. |

Super theory game changers. Ah the game changers, those nuggets of knowledge that can shift in a blink whole paradigms of understanding. Here we liken them to the steps of the mind mountain we aspire to ascend, upon whose top lives written in stone, the understanding of our own music. This 'start' page is chock full of 'em. |

Some 'changers' are nuts and bolts theory and others are in artistic perspective. The nuts and bolts stuff should be rote learned, thus committed to memory for quick recall. For this knowledge is mostly a just dozen symbols or so placed in their unique magical orders. We rote learn the streams of these symbols that become songs. And given the improv nature of our Americana musics, creating music from memory, we'll be sure glad we did. |

The art perspective changers are probably just more like 'food for thought.' For while they too are theory based, they are 'opinion theory based', which may raise some eyebrows I'd imagine. Just use what works to expand your dreams, your ability to focus on your music to further your work. Stay hungry for more, always stay hungry for your learning. |

For we each will end up building 'one game changer upon another', their way stacking and placement based on how we learn and what we already know. Purely natural that our own understanding of music will evolve as we work at it. When new ideas evolve, share them with your fellow musicians and see what they think. |

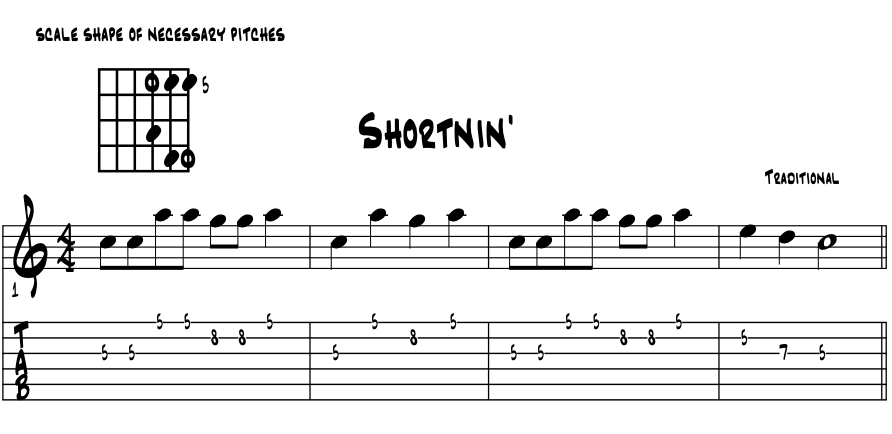

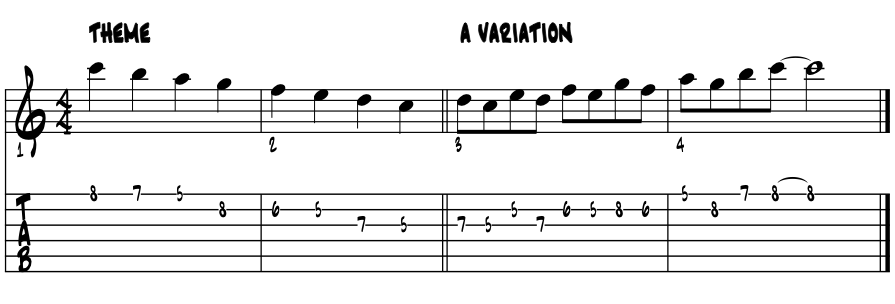

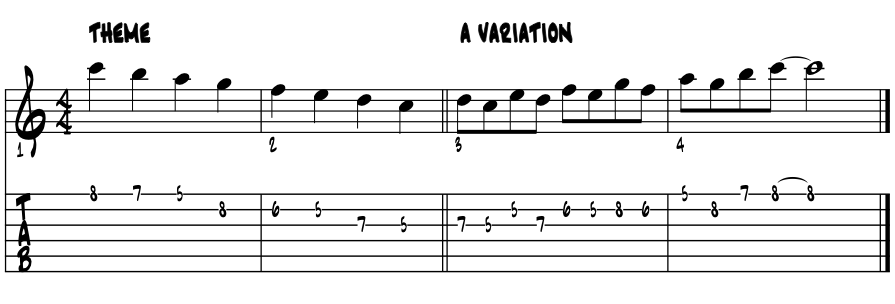

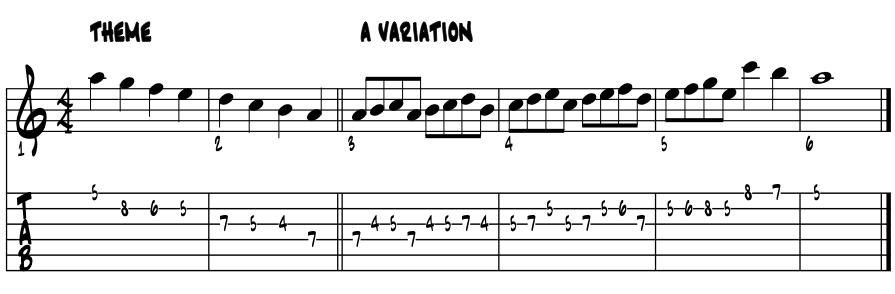

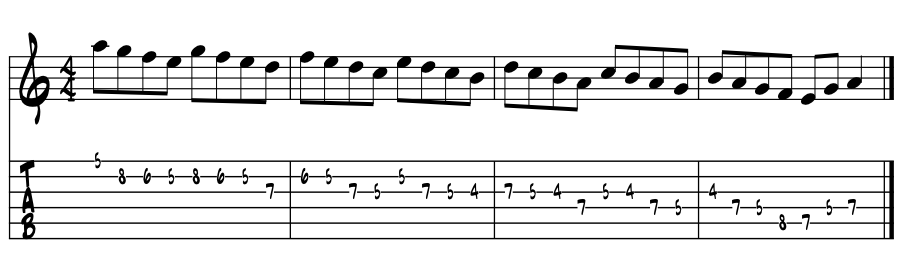

Learn melodies. Playing a real melody that we might already know is a great place to start. If you got a git tune it up regular. No git yet? Just sing along. Know this melody yet? "Shortnin"? Goes way way back into our Americana. In C, here's the 'hook' of the line. Example 5. |

|

Just the four bars? Yep, easiest place to start, with a four bar phrase. We see that a lot of these in our music. Riff on that scale shape up and down the neck a bit, for this is the center shape of what was once termed the 'box' scales, might still be too. Cool? Here's another possible 'game changer' for understanding your music. |

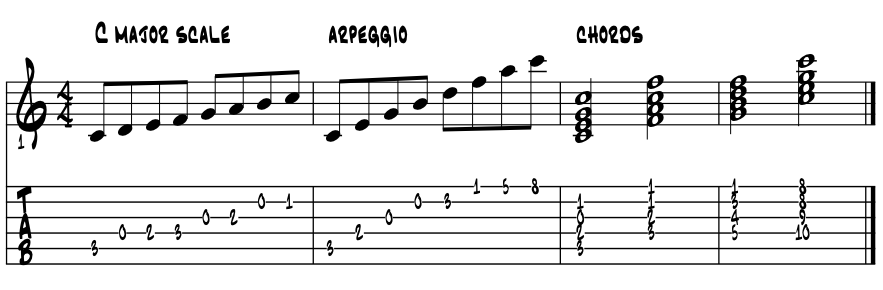

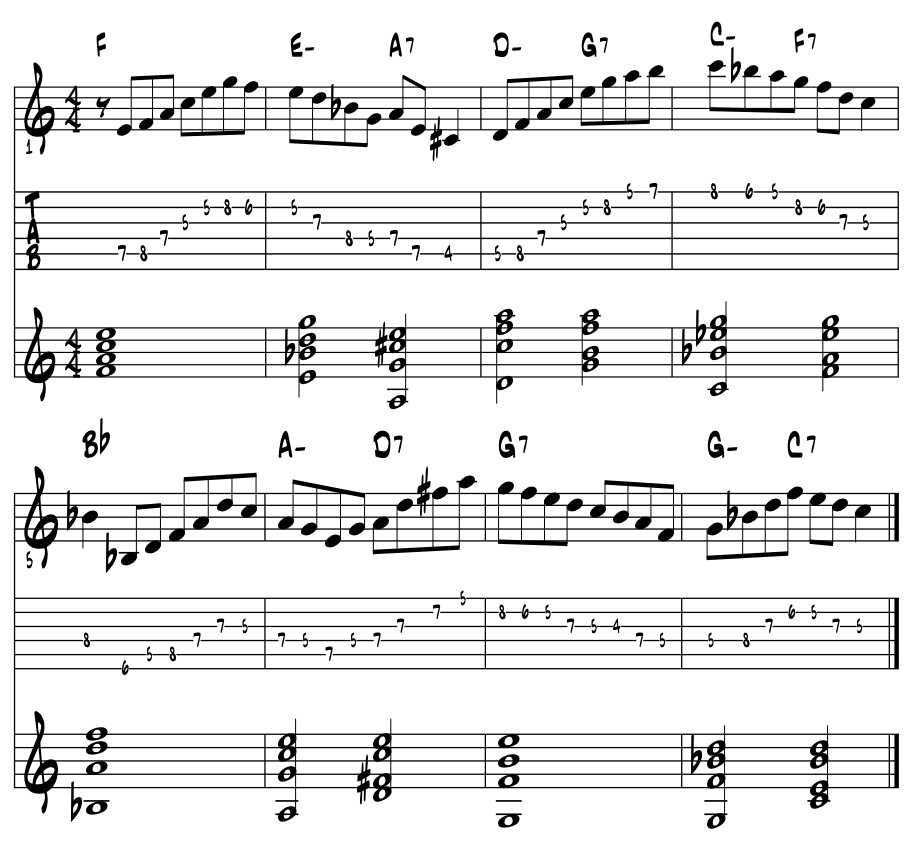

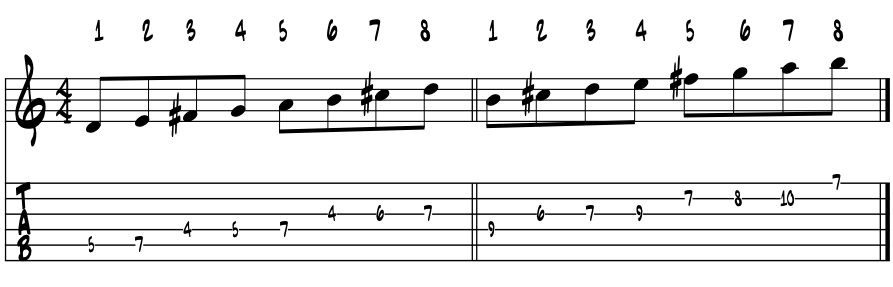

Three in one; scale / arpeggio / chord. The basis of our Americana music flows from the relationships between which pitches we group up together and how we sound them out. As theorists we think of a 'group of pitches', such as the 'G' major scale, from which we can create our scales, arpeggios and chords for this key center. Thus we can create a scale, an arpeggio and chords from the same group of pitches. These become the diatonic core building blocks of all our musics through all our styles. |

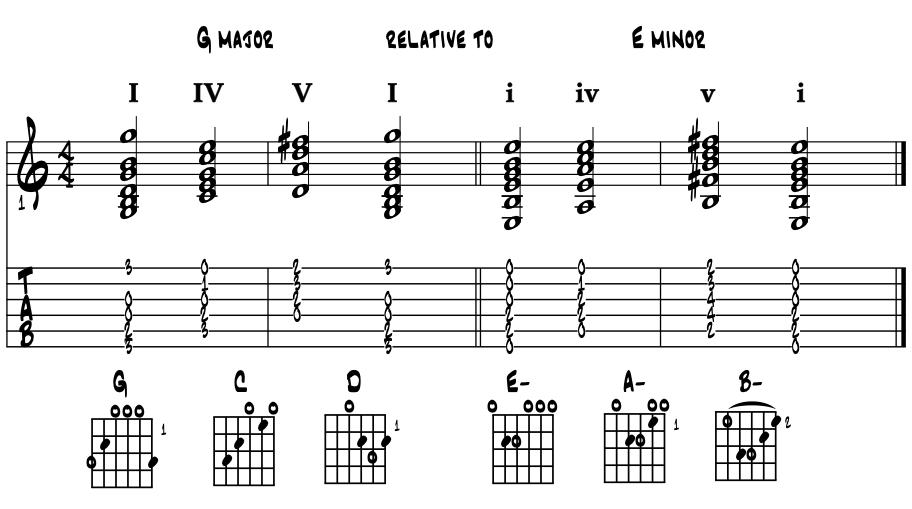

In this next idea, we change keys and use the group of pitches that form up the 'G' major scale. Guitarists love the 'G' / 'E' minor key pairing for the way their pitches lay out on the guitar's fretboard. This layout, covering a full 12 frets, becomes the basis for the jazz guitar method included in this text. Dig this super theory game changer of musical pitch evolution; scale / arpeggio / chord. Example 6. |

|

Cool with this bit of the puzzle? Same pitches, so all diatonic. Reconfigured to create the three main components for our composing palette. Guitar is the rare instrument that gets all three possibilities. Plus, we can bend strings, the pitch of a note. What's not to love :) |

Please rote learn. That the pitches of a scale are sequenced step by step. These steps are the half step, one fret, and whole step interval, a two fret span. Arpeggios are created by skipping every other pitch of the scale. Known as a 'leap', these wider 'skipping' intervals are how we measure the distance between an arpeggio's pitches. Known as '3rd's', they are either major or minor. |

So we simply skip a step between each of the scale pitches to build arpeggios? Yep, arpeggios become 'every other pitch' of a sequence of scale notes / letters. And chords? In creating chords, we simply divide up an arpeggio's pitches into groups of three, four, even five pitches or more. We stack them up one atop one another, and sound them together as a chord. Cool ? Still thinking in 'G' major, here's a chart of the stepwise scale letter name pitches becoming arpeggio skips of major and minor thirds. Example 6a. |

steps |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

G major scale |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

leaps |

. |

maj 3 |

min 3 |

maj 3 |

min 3 |

min 3 |

maj 3 |

min3 |

G major arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

Cool ? It's as simple as that really; scales into arpeggios, who's pitches are stacked and sounded together as chords. A super game changer no doubt ! :) Run these same pitches 'E to E' for the key of 'E' minor. Then for those so smitten, run this theory through the remaining 11 keys for the whole tamale :) |

Understanding this evolution of our musical components from scale into arpeggio into chords can be a game changer for so many us. They form a perfectly closed loop of pitches. As such, any one pitch can become a start point creating its own center of gravity and corresponding scale, arpeggio and chords. These we commonly call the modes. If you're a jazz leaning artist reading here, and are looking to play through chord changes, and are challenged spelling chords, this scale / arpeggio / chord evolution is the solid key to acquire. Simply stop here, master this theory, and you will then own it forever. And next up? Why ... just another stgc'r of course :) |

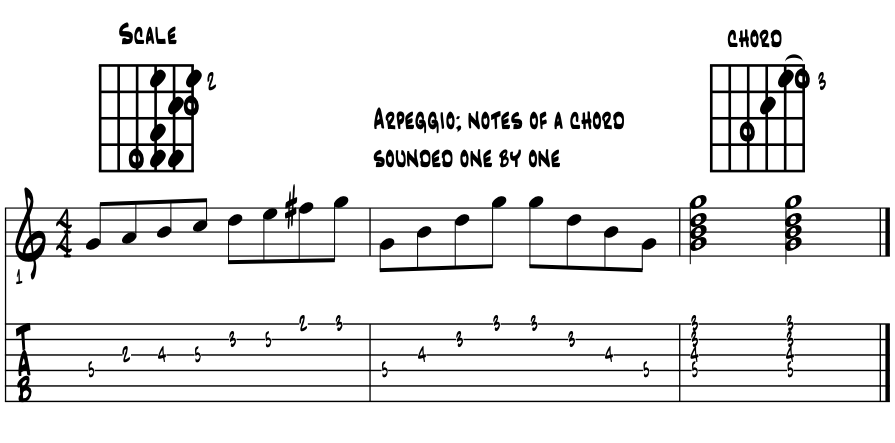

Americana time. This next sequence of ideas form the basis of how we motor our Americana musics along. There's a couple of key skills knitted together to create a basis for understanding Americana time. Learn them here if need be please. |

Time, timing, tempo, rhythms, a groove, a feel etc. These are all terms we use to describe the flow of our music as it moves through measurable time. Clearly found in the 'walking along' of marching band music, three essential beats / rhythms have historically combined to base and create our Americana musical time. These are; the big four, the accenting of the 2nd and 4th beats of the big 4, and the triplet figure, which places notes together into groups of three and creates the Amer ~ Euro gallop. All combined ? We make swing :) |

Once we understand the big four beat of four quarter notes per measure, so much Americana music becomes possible. Known as 4/4 time, it is the same 'boom boom boom boom' pulse found throughout all of the world's music. Back in the 1880's or so and then forward, some of our Americana styles of music started to accent the 2nd and 4th beats. Once there's this 'backbeat' feel in the big four, any sort of triplet starts the Americana swing in motion. And the rest as they say, 'is history.' :) R. O. ! |

Counting measures of a four bar phrase. In this first idea about time, count so that the first number in each group corresponds along with the appropriate measure number in the phrase. Count four bars thus. Example 7. 1 2 3 4 / 2 2 3 4 / 3 2 3 4 / 4 2 3 4 and repeat ...

|

|

In most songs there's usually a balance of elements, like a mobile sculpture that balances elements that float through the air; looks magical. In our music we have phrases with a rhythm moving through time, like when we talk, and in music with a steady rhythm in time, we can count along and make things into definite shapes. Please count out the following phrases, to initiate your learning and just strengthen up your skills if needed. |

Two bar phrase. Count and loop. 1234 2234 / 1234 2234 etc. |

Three bar phrase. Count and loop a couple of times. 1234 2234 3234 / 1234 2234 3234 etc. |

Four bar phrase. Count and loop a couple of times. 1234 2234 3234 4234 / 1234 2234 3234 4234 etc. |

|

Eight bar phrase. Count and loop a couple of times. 1234 2234 3234 4234 5234 6234 7234 8234 / 1234 2234 3234 4234 5234 etc. |

|

Counting measures of a 12 bar blues. Here measure counting for a 12 bar blues. Example 7a. 1 2 3 4 / 2 2 3 4 / 3 2 3 4 / 4 2 3 4 5 2 3 4 / 6 2 3 4 / 7 2 3 4 / 8 2 3 4 9 2 3 4 / 10 2 3 4 / 11 2 3 4 / 12 2 3 4 ... and back to the top. Cool? Do this exercise a couple of times and you'll own the 12 bar blues form forever. Then ya just have to figure out how to play it but at least you can now count along and know where you are in the blues song form with the rest of the band, really makes all the difference when the band starts cooking :) |

Is everything on Americana radio a four bar phrase? Well maybe not but don't be too surprised how true this might turn out to be in a lot of the music that is on our radios. Thankfully we can always go to the radio and check in, see what length of phrases are rockin' the airwaves. Tune on in to any Americana station and snap fingers or clap along on the 2 and 4 beats, and just keep counting along. Look to find the beginning of each phrase as '1 2 3 4, 2 2 3 4 etc. And use this simple method to count any number of measures in 4/4 time. |

For the triplet, find a three syllable word, one for each of the three eighth notes. 'Trip-a-let' works fine or 'van-nil-la' and 'choc-co-late' and 'straw-ber-ry' too :) Ex. 7b. |

|

Feel the pulse from 2 and 4? Cool with the snapping your fingers along? If so then you're creating the pocket and groove of all Americana, and congratulations. It's also a fine way to count things off with the band. And how about the triplet? Feel a bit of the gallop that makes it all seem to jump a bit? The gallop is built right into the Americana DNA. Been around forever now, creating the gallop leads to feeling the physical 'pull' of swing. Just take your time and enjoy this discovery, for it is a building block for a lifelong pursuit of mastering time. |

The easy part, what swing is. Tis quite a challenge to teach someone how to swing. There's just so many individual moving parts ... plus, we each swing our own unique way. Teaching someone what swing is, well that's just a lot easier, a horse of a different color. And the easiest way to teach it? Is to create a way for someone to feel the bodily physical effects of 'swing.' |

The pull of swing. Click on Franz and count yourself into the clicks, finding 2 and 4 with your snaps. Do this by simply saying '1' before each click. So, 'one / click / one / click.' Do this for a spell and then add your finger snaps to the clicks. So, '1 / snap / 1 / snap / 1 / snap.' Now your finger snaps are on the 2 and 4 beats and we're moving through real time :) We're now actually grooving along 'in the pocket' so please ... don't stop :)Here's Franz, set at 60 b.p.m., to provide us some clicks to lean on into. Now, try to wait and hold back your snaps a bit. Be 'late' to each of the clicks. Keep this going for a bit. Feel some pull in the time? Hold back ... a wee bit late with your click ? Feel something there ? Cool. That pull is swing. Want to swing harder? Then try to wait longer to snap your fingers on the clicks. The feeling of the 'pull' gets stronger yes? Wait too long and fall off the 'back' of the beat? Oh well that happens :) Just figure out a way back into the pocket and commence a swinging on :) |

Feel it? Cool. So that sense of a physical, bodily 'pull' between the unaccented beats 1 and 3, and the accented beats of 2 and 4, is the essence of Americana swing, and how it physically feels to an artist as the musical time moves along. Now all we have to do is to figure out how to harness the 'pull' and work it into playing our notes and rhythms on our instruments. R.O. ! |

|

Now the hard part. Feel the pull? That's the physical sensation of swing. Easy. The hard part? That each of us must figure out how to create this sense of 'pull' in our own musics, our sense of time, rhythms et all. We still must physically 'push the buttons' to recreate this sensation of 'pulling' or 'stretching' musical time and ... mix it into the groove around us. This is one solid reason that we jam with other cats, or a super solid reason to work with a metronome etc., we get real musical time to lean right on into. Our metronome in practice becomes our drummer in the band. |

"The drummer; he inspired me to play like no one else I have ever met. |

wiki ~ Chet Baker

|

So does it make you smile when you find the clicks and 'pull' back on your snaps ? Cool, and no surprise there. Swing is a very pure joy :) You, me and everyone it reaches digs swing's joyful magic! We got to pause right here and now to thank Mr. Louis Armstrong, credited with swing's discovery and invention ! So join now, especially classically trained up cats, with Louis and find this physical sense of pull to interpret melodies and bring it with your rhythms to share with all and be truly truly golden forevermore :) |

|

It's all in our syllables, the easy part, part II. Forgetting the lyrics of the song for the moment and any personal embarrassment for what's to follow here, an easy easy super sure way into internalizing the pull of swing is to simply sing melody lines, and get those to swing in moving beats of time. For if I swing when I sing, I got it. For if I swing when I sing, I got it. For if I swing when I sing, I got it. |

Then I just have to figure out how to transfer the way I sing and swing a melody and make those sounds on my axe. 'If I swing when I sing then I know it's a thing :)' So, the syllables we sing are a first key to unlock this pure time magic of swing and begin an evolution of our whole musical being. To start, turn the syllables such as ... ... te te te ... into ... twee twee twee ... or ... ... de de de ... into dwee dwee dwee ... :) The more staccato 'te' and 'de' gain some legato in 'twee' and 'dwee.' In doing so we get a little less definition in the syllable, but gain some wiggle time to negotiate the swing. We each find our own way in all of this, and how we scat sing is a refection of our artistic signature, who we are and what we bring. The 'negotiate' part is all about creating the feel of swing with other musical artists. Just listen close, sing your swing and play it :) |

So, back to the drawing board. Have you found a few melodies from way back in your own life history yet? Remember the first melodies ya learned as a kid? Lots of great old melodies included here. Find one and make it swing your way. For if we swing when we sing then all we need to do is figure out how to transfer it over to our instruments. Sing the line, play the line? Exactly. Can U bring some swing to this lil' ditty from wayback ... ? |

|

The gallop. Just turns out that there's a couple of extra tricks we have to get things grooving in a swing feel. Along with the triplet, the gallop, as its name implies, is a rhythm that once set in motion, has a way of creating a sense of acceleration and forward motion in time. Here borrow the lick from the classical music book, the "William Tell' overture by Rossini. Here in 'C' major. Example 8. |

|

|

Feel that sense of motion? Cool. If new to all this, it may take a while to figure out how to get this motion into your lines. The awareness, of knowing it exists, is very often the first step to discovery. |

The 'chickadee' boom and the zero wiggle. Ever heard of this lick? It's old school for sure and more for bass lines, but is just too cool not to mention here also when starting out. For some, it'll be the game changer for getting their lines to swing, and swing harder and harder, once your ideas are already getting up off the ground, gettin' some air as they say. 'Cboom' is the bowstring :) |

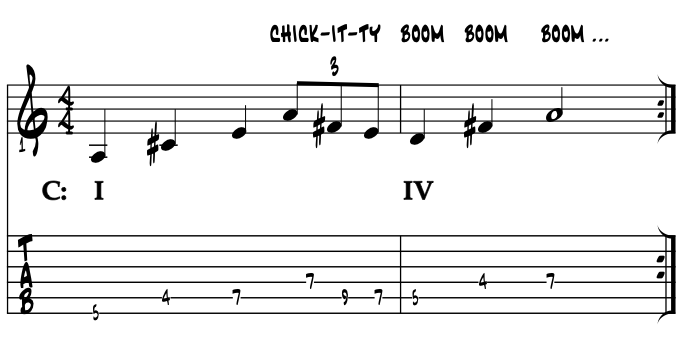

The 'chick a dee' is clearly a funny, three syllable word that we can easily apply to the three notes of the triplet rhythm figure. We use it to create a sense of forward motion and accent towards the downbeat of any measure, leaving zero wiggle as to where the music is going. Here in a walking bass line, super cliche chictyboom motion to Four in the key of 'A.' Ex. 9. |

|

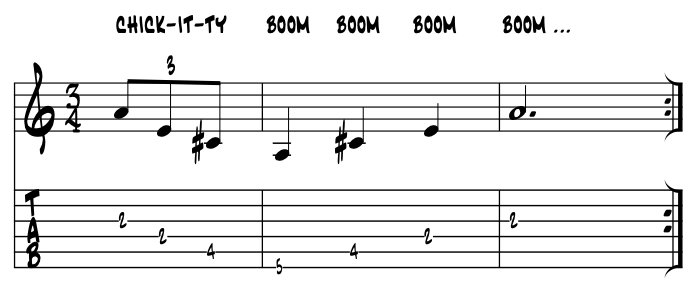

Sense that motion to Four ? Cool. If U B new to all this, may take a while to figure out how to get this motion into your lines. Knowing it exists is always a solid first step to discovering a magic of musical time, rhythms and motion. Here we kick the 'boom boom boom ... ' of the big 4 off with a 'chictyboom' from way back. Ex. 9a. |

|

Sounds like an intro to a slow blues huh? Yea, sure does. Just another way to spice up our Americana lines. |

Hear the real deal. Now to create some 'time' closure for this 'start' discussion. Flip the switch on a radio and spin your radio dial to any AM or FM station and find some sort of rockin' poppin Americana music and listen in. In any Americana music on the airwaves, there's a super good chance that there's the '2 and 4 pop' in the mix, usually on the snare drum. Snap your fingers on the 2 and 4 and count along measures; 1 2 3 4, 2 2 3 4 etc. |

Once you've found the pocket, have counted in and found its 2 and 4 pulse, click along for a spell. With your 'locked in' snaps / claps on 2 and 4, begin to hold back on your 2 and 4 against the clicks off the radio. Feel the pull? Cool. No? Keep trying, for it's there somewhere :) |

Feel the pull? Cool. But wait ... :) The radio is playing a rock tune. Exactly. Creating this pull in a rock groove is often termed the 'big beat.' From the Doors of the 60's on through to Van Halen in the 90's, the big beat rocks the house. And in a sense it's the same swing, same sort of 'late pulling' on 2 and 4 that can live in all our styles. Oh, and don't forget the accent :) For many of us, ya just can't accent 2 and 4 too much :) So rock swings too? |

Now spin the dial to the next station with music and repeat the process. Find 2 and 4 in the mix and snap or clap your hands along. Count some measures, look for the beginning of the four bar phrases. Most times there's a fill of sorts to mark their end / beginning point. Determine a style ? Can you feel the 2 and 4? Create the swing in this style too ? Hold back on your snaps ? Feel the pull against the 2 and 4 ? |

Spin the dial and off to the next station, same process. Anytime there's a 2 and 4 and we snap along we'll find the swing right nearby. It might be subtle or might be wide, we might have to make it up ourselves too, but with the 2 and 4 pulse in 4 / 4 time we easily can. Any style? Yea pert near any style will swing. |

Spin to the Euro classical music station. And sure enough, the 2 and 4 vanishes. Poof. Gone. Crazy huh? Yea there's like zero 2 and 4 in classical music. In this library of music, beats 1 and 3 rule the day. Ever see them cats count off a thing by snapping their fingers on 2 and 4? Nope ? Well neither has anyone else probably, because that's not their thing. No 2 and 4 ? No swing. Simple as that. In 3/4 ? Yes, absolutely swings. |

Teach any legit player to snap their fingers on 2 and 4 of a big 4 beat and at least they'll have a way into getting into swing time. Some historians will say that back in the 1880's it was legit players, who socially pushed out of their legit work and into the honky tonks, that birthed the ragtime style which became jass, which became jazz forevermore. And ragtime is some very serious music requiring some very serious chops to even contemplate performing, let alone compose and arrange songs. |

|

New spin. So on then to the next radio station of Americana music and guess what's back? Right, prolly an accented 2 and 4 has returned to create the core 'dance' in all of our Americana musics. For in all our Americana styles, there's a subtle to obvious 2 and 4 pop, that basic beat that potentially brings the swing and thus, usually fills the dance floor :) |

Last, practice counting off music in 4/4 time. Find the tempo of your song. Adjust your inner tempo to the clicks of a metronome. Make the clicks the 2 and 4. Simply verbally count a '1' before the click. So, '1' / click, '1' / click, '1' / click etc. Then verbally add in the numbers 2 and 4 for the beats / clicks. Count it in to start. Here's Franz for some clicks. Example 10. |

Quick review. These musical time ideas and exercises are some giant steps to master for the newly minted theorist. Hopefully in just trying them out you'll know what swing feels like. A first step to mastery of its magics. Getting your music to swing is now all about how you work it, transferring what you feel into your rhythm expressions. Working with a radio or having real clicks to lean into, unlocks the secrets of 2 and 4. |

"A problem is a chance for you to do your best." |

wiki ~ Duke Ellington ~ |

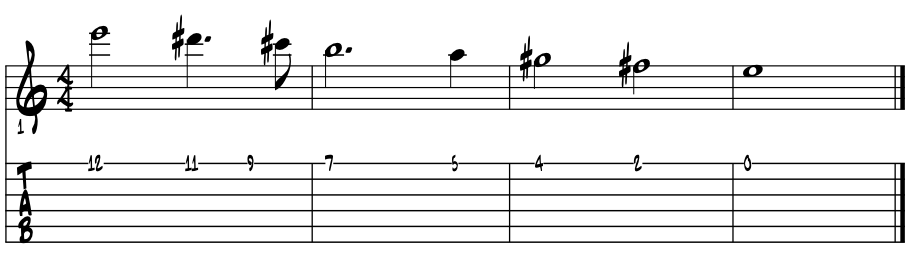

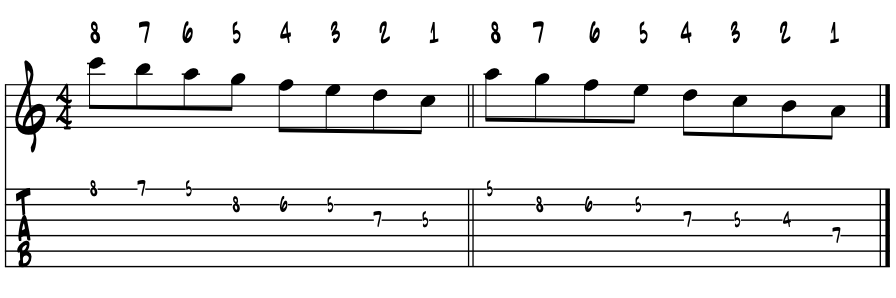

Diatonic, the 'key' word. Diatonic, just one of a couple of ways to refer to one of our very oldest Americana melody maker group of pitches. Major scale, Ionian mode, relative major / natural minor are a few other ways. Remember this winter holiday melody? Here in 'E' major, and all pitches sounded on our top string. Examine the diatonic letter name pitches and corresponding numerical equivalents for 'E' major. Example 11. |

scale # degrees |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

E major scale |

E |

D# |

C# |

B |

A |

G# |

F# |

E |

|

Sound familiar? Cool, a pure diatonic melody. These seven pitches are diatonic to the key center of 'E' major. The octave '8' for the perfect closure. This is great line to run through the 12 major keys. Ever done that? Run one major key melody through all 12 major key centers ? Oh and, nice to have a melody line on just the one string :) |

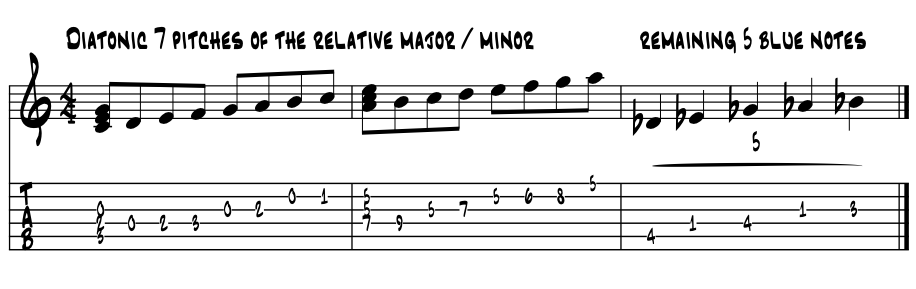

Rule of thumb. In academia, while discussing the various theories of Americana music associated with compositions written in a chosen key center, the basis is this concept of diatonic. Harvard Brief describes diatonic as originating from the Greeks, and meaning 'through the tones.' |

These tones for us today are the 7 / seven pitches of the diatonic scale, creating a key center while leaving five remaining pitches of our original 12. These remaining five pitches, in our Americana way of making music through the styles, often become the blues notes in melody and color tones in harmony. |

The idea of 'diatonic' bases all of our theory in thought, and process, as it defines any one pitch, arpeggio or chord within a key center. Once we know its root source, we can sort out even the jumbliest jumbles of pitches to understand where they come from and their relationships to one another in the music under scrutiny. |

We can simply ask 'what key center is this pitch (es) diatonic to.' From there we untangle and build. Nine out of ten times in most Americana musics our pitches are diatonic to the key of the music, from a closely related key center or simply adding in a bit of the blue hue spice of coolness. |

So we only have 12 different letter name pitches? Yep, in our theory musings we've only get the 12. Of course we generally get a couple of octaves usually but historically, that was not always the case. Know these 12 pitches ? And can you find identify them on your ax and or at a piano keyboard? Example 11a. |

|

Why this theory plays so heavily right out of the gate is due to the near and ever present influence of the blue notes in the Americana sounds we love. We need the 'diatonic seven' to build up the chords, and remaining five are the blue notes and color tones. And are they diatonic? No, they are not diatonic to a key center as defined just above. We theorists 'borrow them' to jazz up and bluesify the seven diatonic pitches in innumerable ways in both melody and harmony. |

A problem? No, not at all and really only my problem in trying to describe the nuts, bolts and art of the music in theoretical terms. But as long as you're hip to the idea of diatonic, and what it implies, all is groovy in Theoryville. Part of what makes American music so wonderful from a historical / global / enjoyment perspective is the artful blending and ofttimes continual improvisational merging of the seven diatonic pitches with the five blue ones. This all created by artists making new art in the moment. |

Our dear ancestor's music from across the pond to the East, often termed European classical music, has historically been diatonic. Every pitch in any music 'theory assignable' to a diatonic key center or borrowed from one. Any real blue notes rubbed over a diatonic harmony? No. Any backbeat accent on 2 and 4 to swell the pulse and open up the groove to swing? No. At least in our Americana sense. Any improv to speak of ? No. Yet this European influence becomes the basis of all of our Americana harmony. How so ? |

Well ... most everything to do with tuning the pitches, and building up of these pitches into chords, historically originates from Europe. All blues' hue magics are purely Americana DNA. Throughout our discussions I call this seven pitch diatonic / five pitch blue note combination the 'blues rub.' We'll feel it again and again as we learn to understand the relationships of combining these two groups of pitches in our music. |

Learn to spell triads / chords. So you're thinking that learning to spell chords might get you another step along to your own private Parnassum? Cool. We at UYM / Essentials do too :) For many reading here, developing the ability to quickly and accurately spell any chord becomes the basis of their theory knowledge and know that for some, that's all they'll ever really need to know to roll through their careers. For in every style that there' chords, knowing their letter names is the game changer. Thus an essential ability. So begin to master this skill now if need be and the rote learn the results; to spell out the letter pitches of any triad or chord. (P.s., its easy :) |

Pick a song find its key. Most songs we have are created in a key center with a set group of pitches that we use to create its melody, arpeggios and chords. These pitches we term 'diatonic.' Most often its the seven pitch relative major / minor group of pitches. These are the same pitches we use to spell its triads / chords. For by relating a triad to a key center, we quickly get its basic pitches and negotiate the rest from there. So, we picked "Oh Susanna" for our song in the key of 'C' major? Cool, let's build up our triad spelling chart. |

Scale degree. So from the above discussion of 'diatonic' we begin anew with seven pitches, upon each of which we can build a diatonic triad. That in each and any key center we can number the letter name pitches of our chosen, parent scale. We call these our scale degrees. |

Mostly one (1) through (8), which gives us our octave closure, we then simply fill in whatever letter name pitches of the key center we choose. Examine the ascending numbers of our scale degrees. Example 12. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

A bingo. Easy enough ? Cool. So will these same 1 through 8 numbers apply as scale degrees to all of our 12 major / minor key centers? Yep. And if you understand this ya just got a bingo :) |

Apply letter name pitches. When we theorize within a key center, we can use these numerical designations to locate what we're talking about. Do these numbers also represent our root pitches for chord progressions as in One, Four and Five? Yes, these are those numbers too. Let's add in the letters that represent the notes of our chosen key center. We're thinking 'C' major here yes? Example 12a. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

Ah, recognize the diatonic pitches of 'C' major ? Just all the white keys on a piano right ? |

|

Ah, recognize the 'C to C' octave closure; One through Eight. No loose ends allowed, in theory :) So now we've a corresponding number for each letter name for a pitch. So when cats talk about the first scale degree of 'C' major the pitch is 'C.' Sixth scale degree is 'A.' The third scale degree is 'E' etc., this is how it all makes sense the world over, well mostly. Cool? Surely rote memorize this number / pitch relationship. Got a hankering to master this? Write out and rote memorize this chart for our 12 major key centers. Minor key centers too? Sure, works the exact same way so why not. Cool with the diff between major and minor ? |

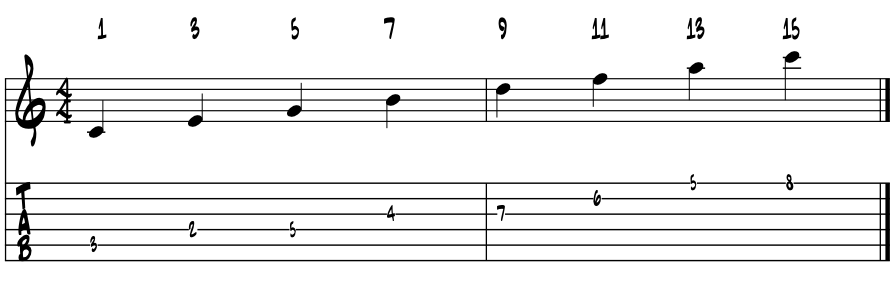

Add arpeggio numbers / arpeggio degrees. Just like adding numbers to scale degrees, we can add numbers to our arpeggios too. We can simply call these our arpeggio degrees. These numbers open up our chord spelling abilities. We spell our chords in thirds, meaning we need to simply skip every other note in our stepwise scale. In doing so we create an arpeggio. |

Skip / leap. So do we skip every other number in our scale to create the arpeggio? Yep, but there's a twist in this as we ascend past and expand our octave closure interval to two full octaves. Really? Yep, we need two full octaves to work this chord spelling magic. Problems? Nope we do this all the time in our theory musings, move into the second octave and retain our perfect closure of pitches. Examine this new set of numbers. Ex. 12b. |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Exact same letters right ? Yep. Is this the source of the three note, '1, 3, 5 of triads ?' Sure is. And 1, 3, 5 are the numericals for building the triads? Roger that Amigo. Let's add in the arpeggio letter names to our scale degree chart. Example 12c. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

|

Clear as mud? Skipped every other letter of the scale to create the arpeggio. See the looping in the pitches of the octave closure? Can you imagine a 'C' between the 'B' and 'D' of the '7 and 9' numbers of the arpeggio? Is that where we get into the second octave? Sure is. Cool with this and 'you be golden', as they say in some parts. |

Rote learn. Just a suggestion here but consider rote learning the letter names of the 'C' major scale and then respelling these pitches into its arpeggio format. And in some ways, speed counts. Rote learn it so that you can spell the letters out in the blink of an eye, or two shakes of a lamb's tail if you live agrarian. Fast? Fast, like learning the letter alphabet as kids. Oh, and leaning towards blues and jazz improv and soloing through chord changes? Eventually run this wee bit through the 12 major key centers by rote; so in writing and vocalizing the sequences ... once begun it goes pretty quick. |

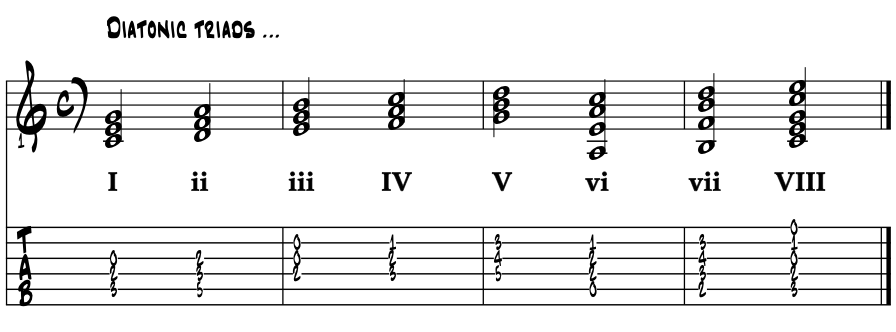

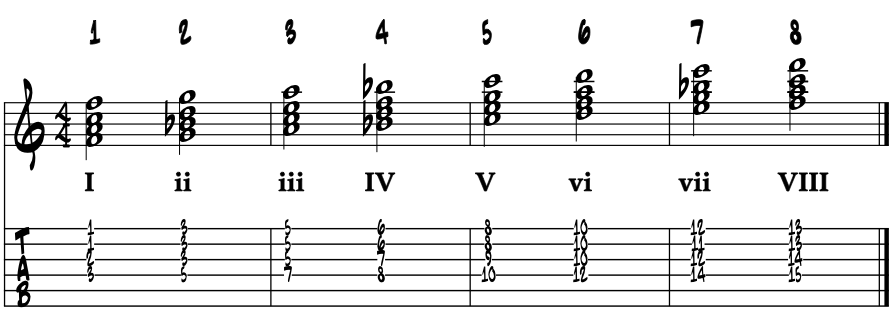

Chord quality / Roman numerals. In our next line of our triad spelling chart we layer in Roman numerals. Luckily with these we get two varieties; upper and lower case, just like our capitol and lower case letters. We theory scientists use these two varieties to designate whether our triad is major or minor in its aural color. Again back to the 'one through eight' diatonic basis, examine the Roman numeral designations of our diatonic triads. Example 12d. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

So from the Roman numerals it looks like we get a few major triads and a few minor triads within each key center ? Yep. Is this the legendary diatonic '3 and 3?' Sure is. Legendary in that 95 out of a 100 Americana songs are based on these six chords. And many of these don't even get to all six, but use just three. 'Three chords and the truth?' Yep. Three chords and the truth. |

Let's spell the triads. So this chart works like this. We decide which chord we want to spell in the key center of 'C' major. Find that note as a scale degree. Then find that letter name note in the arpeggio which becomes the root pitch / 1 / One of the chord. ' 1 = root pitch of triad ' We then read to the right to find its 3rd and 5th, completing the three notes of our triad. Let's spell the triad built on One in the key of 'C' major. Example 12e. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

I |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

CEG |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Triads need a root, 3rd and 5th. Cool? Rocket science this is surely not but it is surely a potential game changer for our intellectual evolutions in understanding our musics. So the triad built on the 1st scale degree of the key of 'C' major is a major triad ( I ) spelt 'C, E, G / 1 3 5 / a root, a 3rd and a 5th. |

Spell the triad built on Two. So in spelling Two, we again simply need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart for the letter names of the pitches. Example 12f. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

ii |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

D F A |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Say what? See how we moved the arpeggio degree numbers so that the #1 is now above the letter name of the root pitch of the triad we're wanting to spell ? Magic revealed? Magic revealed. Try for the Three chord? |

Spell the triad built on Three. So in spelling Three, we need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart. Ex. 12g. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

iii |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

E G B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Again we simply need to slide our arpeggios degree numbers to designate the 3rd scale degree of the 'C' major scale as the root pitch of the triad. See how this is unfolding ? The rest is a breeze n'est-ce pas? |

|

Spell the triad built on Four. So in spelling Four, we need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart. Ex. 12h. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

. |

IV |

. |

. |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

. |

F A C |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Spell the triad built on Five. So in spelling Five, we need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart. Ex. 12i. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

. |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

. |

. |

V |

. |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

G B D |

. |

. |

. |

Spell the triad built on Six. So in spelling Six, we need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart. Example 12j. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

vi |

. |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A C E |

. |

. |

Seems we ran out of chart there. Did you figure out the necessary process? No worries really, we just loop back and keep on spelling. Ancient wisdom says; 'all things music theory always loop back to their starting point for perfect closure.' When we add colortones to jazz up the triads, this will happen a lot as we spell the pitches of the 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th chords. Cool? Everything loops. |

Spell the triad built on Seven. So in spelling Seven, we need a root, 3rd and 5th. Examine the chart. Ex. 12k. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

vii |

. |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

B D F |

. |

Easy enough eh? And Eight takes us right back to where we started. Perfectly closed loop? Yep, perfectly closed. Example 12l. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

. |

. |

C major arpeggio |

. |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

VIII |

diatonic triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C E G |

The whole triad spelling tamale. Putting all of the charts together we can create our official 'essentials' chord spelling chart 'C' major. Example 12m. |

... rote learn this chart ... rote learn this chart ... rote learn this chart ... |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEG |

DFA |

EGB |

FAC |

GBD |

ACE |

BDF |

CEG |

|

Now ain't that a beauty :) Master this chart and how it all works and own it forevermore. Find it on a piano to hear the theory magic and ease of sounding it all out. Another giant step forward for the emerging theorist, spelling chords goes right along with theory analysis of written scores and with improvisation, especially as we move from blues and rock soloing over the changes and into a more jazz approach of 'soloing through the changes.' |

This 'through the changes' is the jazz improv styling that began to happen in the later 30's and forward, as players began to use the chord progressions of a song as the basis for their improvised lines. Arpeggiating the pitches of the chords becomes the way non-chordal instruments; i.e., the horns, can super clearly tell their harmonic story. |

For those readers here leaning to jazz, we've a very thin but absolute sure link to Charlie Parker through Jackie McLean, whom a dear friend here in AK had a chance to study with back in the 70's. During a lesson, Mr. McLean wrote this on the music under scrutiny that day in their lesson. Example 12n. |

|

'Spell' is the last of the three words in McLean's own handwriting, and we can just see the D major 7th arpeggio pitches in the measure on the left. So when shedding and sifting through for ideas, simply spelling the chords with his horn, as the changes flow, by is a way to search for and generate new ideas. That's they way Eli explained it to me. |

~ super theory game changer ~ |

Cool with triads? Now adding the 7th. We can easily add the 7th to each of our diatonic triads. In doing so we evolve our chords beyond the three note triads that form the basis for traditional folk and country sounds and begin to jazz things up towards the blues, rock and on into pop styles and forward to into jazz. Easy start with this next chart, we add a 7th to a 'C' major triad. Example 13. |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Cool? RO! Not cool ? RO! Just reading left to right up the arpeggio pitches yes ? In adding a 7th to a '1 3 5' triad, we open up new pathways to explore. The idea of a 'chord type' evolves, there's additional color tones and principles of chord substitution. Of course our musical styles will most likely transition as we move along this 'adding colortones' pathway, as we increase our number of pitches in the mix. |

What we gain / chord type. Once we get a sense of this structural 'type' of a 7th chord, and create its three essential categories; of ' 2 ~ 5 ~ 1 ', our whole tamale of mathematically logical, perfectly closed, tuned and balanced system of pitches becomes infinitely more three dimensional harmonically. Just by adding a 7th to a major or minor triad? Yep, the 7th pairs with the 3rd and away we go into new possibilities of the art of creating tension and its release as our stories unfold. |

A 'parent scale.' By adding a 7th and thinking chord type, we have the option to further expand our harmonic palette of colors with additional color tones and to better ( ? ) create a 'parent scale' for each chord. Now we're examining each chord within a progression and exploring for coolness with a broader filter than just say it's original diatonic origins. Knowing that we use our chords and their progressions to suggest bass line stories, melodies and improvisation, both over and through a song's chord progressions, thinking of a chord's parent scale potentially expands our borrowing options for pitches to create our ideas with. |

Quick review. So by just adding a 7th to a triad we get this paradigm shift of sorts? Pretty much amigo, adding the 7th is a portal for new colors to add into the mix, bringing us new ways to jazz things up thus creating new ways to express the art in our hearts. For there's now a chord type, a related parent scale, chord substitution and a simplification of elements involved by chord voicings; that any Two / Five / One chord voicing or for guitar, a chord shape, can be mixed and matched together to create cadential motions, vamps and grooves. |

Super blues / jazz guitar learning accelerator. Once the idea of 'chord type' and its related properties of 'chord function' are accepted, we can break down our learning of chord voicings into one of three categories; One, Two and Five. We then can rote up on a say a half dozen voicings of each one, then mix and match them as our creative intuits. Add in what note we need 'in the lead' of a chord and the diminished chord's property of inverting itself by minor 3rd intervals, and we've some potent ingredients to jazz our interpretations of the music, its improvisations et all. Toss in the 'half step lead in' ... and surely a moment of kaboom ! :) |

Adding a 7th to diatonic triads. So adding the 7th to each of the diatonic triads is a snap really, as we'll just tack on the next pitch in the arpeggio to the three notes of the triad. Still thinking here in 'C' major, here's the 'tack on' process in bold type for our tonic, One, 'C' major 7th chord. Just like the chart above? Yep, but now with all the diatonic extras to make the whole tamale. Example 13a. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

Easy do yes? Got a hold of this process of spelling chords from the arpeggio ? Cool. Find these pitches on your instrument and on the piano, Sound them out and decide if this chord color is one for your palette. Here's the chart for spelling out the Two minor 7th chord. Example 13b. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

Easy do yes? Here's the Five 7th chord. Example 13c. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

. |

. |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

Cool ? Just spelling chords from arpeggios, creating our arpeggios from a scale. In this case the major scale. Scales are the ancient groups, and all varieties form their loops. And for guitar, we do get solid blocks of each of the Two / Five / One voicings / motions, from within our core five scale shapes, which all combined make a path to a melodic and harmonic Parnassus. |

Quick review / spelling chords. Easy do yes? Same for all of the triads and 7th chords ? Yep. In any key ? Yep. Major or minor ? Yep. Call a tune, pick a key, build up its relative major / minor scale, arpeggiate this scale in thirds, pick your root pitch, locate that pitch and read to the right; 1, 3, 5, 7 spell the letter names, and onward to all points beyond ... Spelling chords from these charts is all about the 'slide' of the '#1 root pitch', within the arpeggio degrees sequence. We find the root letter name of a chord, this becomes our root pitch, tonic, #1. We then read to the right as we would normally do reading words in a book. ' 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 ~ becomes ~ C E G B D F A ' ' ~ or ~ ' ' C E G B D F A ~ becomes ~ 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 :) For the other color tones, associated with our fancier jazzier chords, 'b9' '#9', '#11' etc., just follow the same process? Exactly, just continue reading letters to the right of the arpeggio beyond 7 for 9, 11, and 13. And adjust the letter name pitch by half step as needed i.e., b9 is the 9th lowered by half step, #11 is the diatonic 11th moved up a half step. It'll take a bit of study to master, so be patient with yourself. Remember that just like learning the alphabet as kids; rote learn these skills by a combined reading, writing and speaking aloud. |

~ super theory game changer ~ |

The diatonic 3 and 3 ~ simply beyond amazing. Everyone reading here probably knows, and if not soon will, that we can build up a chord on each of the seven unique pitches of a major scale. Numbered One through Seven. What's not commonly known it seems, is that the three chords needed to create the One / Four / Five chord progression, for both major and minor, is in these six chords. All within each key center. Examine the letter pitches in the key center of 'C' major. Example 14. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

1 / 4 / 5 chords |

I |

. |

. |

IV |

V |

. |

. |

. |

root pitches / triads |

C E G |

. |

. |

F A C |

G B D |

. |

. |

. |

And for our relative minor. Ah yes, the perfection of balance and hue from within the ancient loop. Ex. 14a. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

A minor scale |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

1 / 4 / 5 chords |

I |

. |

. |

IV |

V |

. |

. |

. |

root pitches / triads |

A C E |

. |

. |

D F A |

E G B |

. |

. |

. |

So did you already know this? Cool. So what's the kaboom on this? It's a harmony kaboom this time. The One / Four / Five chord progression is the most common basis for our songs. Writer's have called such songs 'three chords and the truth' for a solid handful of decades now. And while any three chords are eligible for this elevated status, the 1 4 5 motions, by far and away, is tops for creating a true 'tcatt' song. |

Diatonic harmony in songs. Furthermore, unless we're playing a really jazzed up song, these six diatonic triads combined, the 1 4 5 major triads + 1 4 5 minor triads, in endless combinations, create nearly all the other songs in our Americana songbook. Near all ? Yep, and have done so for the last couple of centuries or so. Lullabies, folk, blues and rock, bluegrass, country and into pop, even towards jazz to a certain degree, all of theses songs are written with these core six, diatonic triads. |

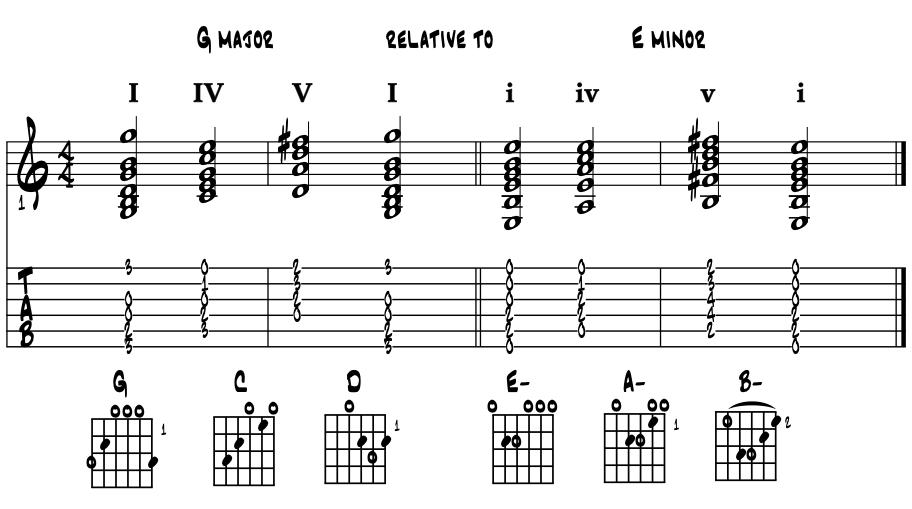

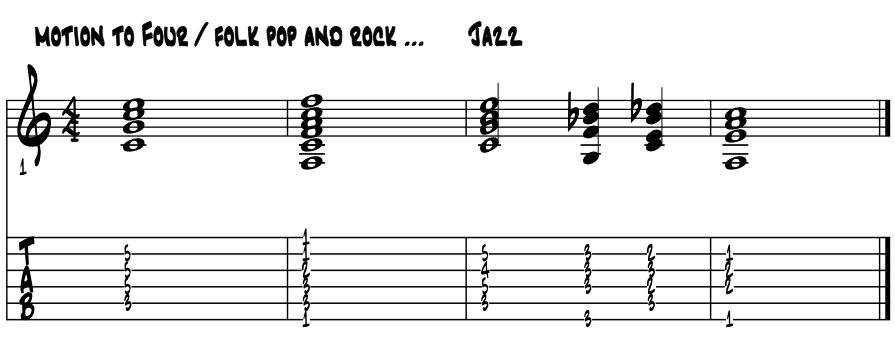

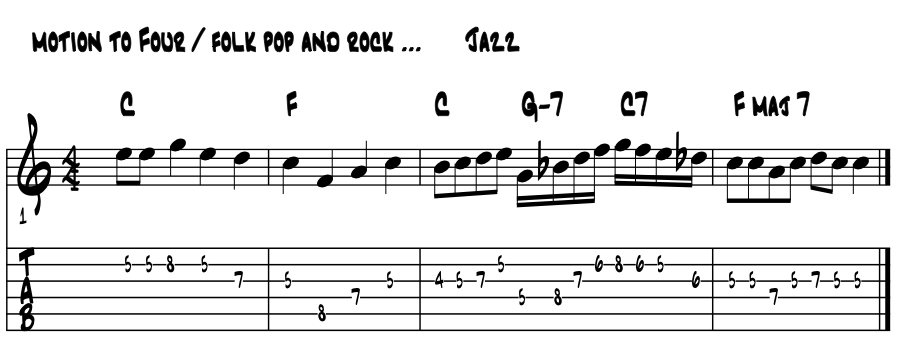

Variations and adjustments on these six chords? Endless variations. Number of tunes written with these six (or less) chords in any and every combination imaginable? An endless number of songs. Songs to be written in this rich tradition? Endless. What's not to love :) Changing key centers, here are the 'diatonic 3 and 3' in G major, using the open chord voicings. Example 14b. |

|

Look familiar? Cool. No? Just start to learn them here if need be. Rhythm guitar players unite ! So there's a fair to midland size shifting here in the understanding of things, we've 'modulated' to 'G' major in our discussions. If a key change is a big deal 'understanding theory' wise for you, no worries, it'll all come together, just stay on your path. |

We switch to the 'G major / E minor' key pairing to line up with the guitar method mostly. Turns out the dot pattern on the neck is now ancient, and builders have been using the same pattern mostly for like 500 years now. Same dots as the earlier lutes? Not sure but probably. There are lutes with fixed frets laid out by the 'rule of 18.' Regardless, the dots show a pattern of grouping the pitches, that gets built right into the way our instruments have the ability to create all the pitches, all the arpeggios and all the chords, in all the keys, fully motorized and in perfect tune all through. Who knew ! |

That in so much of our Americana musics, the diatonic One, Four and Five chords are the principle chords that motor a song along. Placed in various sequences, they drive a seemingly endless array of grooves through a wide spectrum of styles. One / Four and Five. The 12 bar blues, in both major and minor, perhaps the first best of many reasons to rote learn all of this. That we get this three chord group, in both major and minor, from one group of pitches is just downright a shame not to know right now. Termed in this Essentials work the 'diatonic 3 and 3, the sooner a cat digs into this and understands its multipoint magics, the sooner another step to their own Parnassus becomes manifest, is taken and conquered. |

Clear Americana examples of One / Four / Five songs? My 'tcatt's are "Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain" and "Blue Sky." Speaking of blues, again the 12 bar blues form in both major and minor keys could be an easier start point, if necessary and rote learned. Any rockin' of anything in this 12 bar form is going to be totally cored on the 1, 4 and 5 chords. Just might be that the motion to Four is the core harmonic motion of it all, in all of the Americana musics we love. |

Take my word for it :) And if we mix these chords together, this 'diatonic 3 & 3', the 145 major / 145 minor chords into the same song somehow, we now cover the basic harmony of probably nine out of ten Americana songs, spanning through all of our musical styles. Throw in 'blues hue' chord or two and a modulation somewhere and we might be talkin' 10 out of 10 tunes here. The author's own "When You Coming Back" included in this work just by chance has 'em all :) |

And in regards to making melody ... Hip to the idea of 'relative major / minor scale? You mean the major scale? Or the diatonic scale? Or the natural minor scale? Oh, Aeolian mode right? Yea, Ionian mode whew :) Are all these groupings all created with the exact same pitches? Yep, they are, the exact same pitches. One loop of pitches begets all by weaving major and minor together simply by starting from 2 different points within the same loop of pitches. Exact same group of letter name pitches just with different start points within the closed loop. How can this be ? By the 1/2 step locations between the pitches of a group ? Yes, 1/2 step locations between the pitches within any group determines its character. Anything else? No, not really with these '3 and 3's.' Thirds, fifths and sevenths are good. Thus into chord type? Yep pretty much as all six qualify for this lofty harmonic 'type' status :) And we've additional start points as in 'the modes within' of any loop or group of pitches yes? Sure do. Then please add another four or five ways to identify this same group of letter name pitches. We'll do the 'why and how' of this in another discussion. For now, begin to study this mash up of vocab labels by examining the pitches of G major / E minor, our guitar's structural theory core of pitches and key centers. Example 14c. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

G diatonic |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

G Ionian |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

E relative minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

E natural minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

E Aeolian |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

Not too shabby; half dozen groups with the same letter name pitches. Why all the different names? The naming of each group is mostly historical or geographically generated, or both in some cases. Any modal name is way old and from Europe. G major is the common vernacular among folk, country and bluegrass stylings. When 'relative' enters the discussion, here comes some organizational theory usually. From the chart we see that coolness does reign in the simplicity of our letter pitch organizations, it's the labeling of that can often create initial confusion. And how's your knowledge of the fingerboard and the letter names of the pitches these days? Can you find the 'G' / 'E' relatives on your chosen instrument? So, just might be time to lock it all together; pitch location / letter name and theory, when understanding the theory is just so straight forward and balanced. Same pitches for guitar and bass correct? On my four string bass the pitches are the same as the low four strings on my guitar. They just sound an octave lower. So the same fingerboard chart of the letter name pitches works for both instruments. |

Sourcing the triads for the 'diatonic 3 and 3.' With a refinement in tuning of the natural scale, additional coolness awaits as the diatonic 3 and 3 is built right up from these very same pitches. The 1 4 5 major chords come from the major scale and the 1 4 5 minor come from the pitches of the natural minor group. These become the parent scales for these chords. Examine the pitches. Example 14d. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

arpeggio pitches |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

One / G major |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / C major |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

Five / D major |

. |

. |

D |

F# |

A |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

One / E minor |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / A minor |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

Five / B minor |

. |

. |

B |

D |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

Ever seen such a layout of the pitches in this manner ? This is a common way to chart up and spell out the letter name pitches of the diatonic chords. Created from the perspective of the 'G' major center, then 'E' natural minor, we measure and numerically label each of the pitches from 'G' and 'E' as One. These are the root pitches for the 1, 4 and 5 chords. We then spell out their triads as usual from their diatonic arpeggio layout. |

Author's note. This adding of the numbers to represent letters is nothing short of potentially game changing for the emerging theorist. Using numbers instead of letters allows us to project most any theory idea, principle or combination of pitches equally from any of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. This one idea alone can advance our understanding of the entire system more than any of our other 'STGC.' |

And as we add more pitches into the mix; more pitches in a melody, extend three note triads into chords with color tones, expand chord progressions and root motion story lines, through subdivision of the beat and adding measures in our forms, our style of music evolves from the more numerically simple folk side through blues, country, rock and pop and on into the full 12 pitch numeric of the jazz language. |

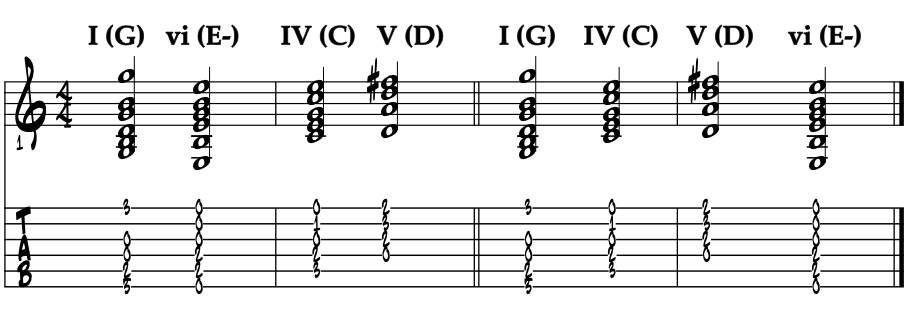

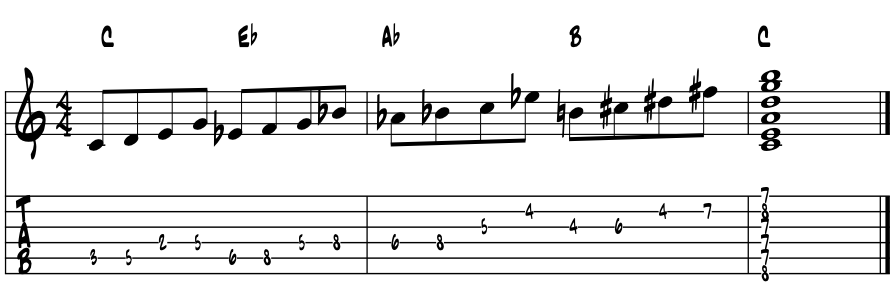

Too cool ! Two sets of One / Four / Five chords, one major, one minor from the same pitches. The ultimate sets of '3's for the Americana harmony mix and match. No end to the chord progressions they might create in all of our styles. Super rote learn these ideas and chords for maximum success. Example 14e. |

|

Wow, in this one musical graphic we get a variety of theory coolness. Diatonic relative pitches and keys, the upper (major) and lower (minor) case Roman numeral chord degree symbols, standard notation of the pitches, string tab note locators and line grids for chord shapes. |

As these chords generously allow for, do consider working in some fingerpicking to help locate your single line melodies from within these big open chords. Sing, hum or buzz along with your melody to get it just how you want it to sound, feel and flow. Make it all dance :) Bass lines often begin by just playing the roots of the chords. Then by using the other diatonic pitches as passing tones between the roots of the chords in a song's chord progression, creating a story line. |

So did you already have these chord shapes under your fingers? Cool. No? Then just learn them here if need be. And did you know they were all diatonically related? Ya do now :) So in learning new chord shapes, try to slowly strum each chord just a time or two then move to the new shape, strum once and move to next shape etc. Simply back and forth with one strum till the new shape is mastered. The strumming is usually the easy part, shifting pitch fingers between shapes the challenge. |

|

OK with the last barre chord B minor in the last idea? Here it is again. As it is the same core shape as A minor just up two frets, the index finger becoming the barre replacing the nut of the open strings. Evolving open chords to the movable barre chords is often a dramatic step for the evolving guitarist, rockers take note. |

Coolness with the relative chords. As mentioned above, these six chords provide the gist of the harmony for all our Americana musics. While of course not always in G major / E minor, most folk through pop styled tunes are based on combinations or chord progressions of these six diatonic chords. A capo often employed to reset the pitches for any other key, most often to better suit the vocal range of an artist. |

For bass, in this sort of diatonic chord motion, connecting the roots of the chords with various rhythm patterns creates a bassline that tells a song's story. Rote learn these changes by pitch letter name and by ear, as there's only six, it is fairly easy. |

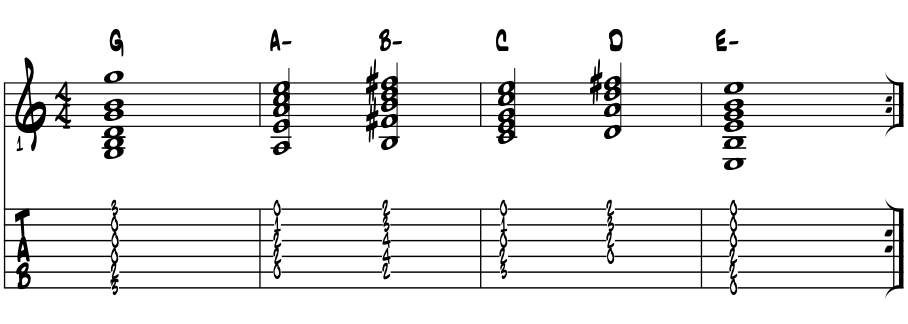

This next idea finds two quite common ways of working the E minor triad, which is built on the sixth scale degree of G major, into the One / Four / Five of G major. Both are used in a lot of memorable songs. Example 14f. |

|

Glad you memorized the chords right ? Both of these motions make for great songs, a solid Americana storyline to tell our tales. Hear anything come to mind ? |