~ the turnaround / cadential motions ~

|

In a nutshell ~ the 'turnaround.' In our Americana musics the turnaround generates the same meaning as most everywhere else; 'it turns us around to go back.' In music we 'turnaround to' a selected spot in the song we are performing.' Most times the turnaround is the last couple of measures of a song's arrangement, and takes us back to the top of the form. Successful navigation of the turnaround helps to string multiple choruses together, and in doing so creating longer solos for cats who have more to say. |

Where is the turnaround. At the end of a song's form. When the melody and supporting chords resolve and come to a rest, if we don't take it (the tune) out and end the song, there's the turnaround that gets us back to the beginning, to start the form over again; for the next vocals, the next soloist etc. The musical content of a written turnaround is usually the original pickup notes of the melody if any and a chord or two that 'progresses' us to the first chord back at the top. Most common of turnaround chords is the V7 dominant chord of the tonic key of the song. |

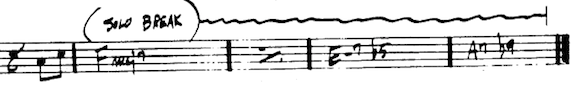

Timing the solo break. A solo break is when the band stops, leaving a few bars open for the improvisor or soloist to fill in with a riff that gets the band started off again. And if 'timing is everything', then the solo break probably invented everything :) For when the forward motion and momentum of the tune we're playing stops on a dime, there's this sort of cliff we're going over, we're free falling a bit till the new voice picks up the rhythm and sets up the return to the top of the form. |

The band rescues all from the fall by coming back in on the downbeat of the first measure, creating a resolution for the solo break, and we're back in business. Most of the beginning challenges with the solo break is in coordinating this free fall sense and timing up our idea to bring the band back in. If new to this, try just honking on one pitch, using a solid rhythm to point everything towards the resolution on the downbeat of measure one. |

The solo break. We can find the solo break in all of our our Americana musics creating some of the most exciting, suspenseful and memorable moments we might ever get to have as improvising musicians. As its name implies, we 'break' the music, the band will stop and pause for just a moment or two, and give the soloist a 'silent window' to create an idea that propels us back to the top of form for yet another go-around through the song's form. |

The solo break is also most often the turnaround. The solo break has traditionally been paired right up in the measures of the turnaround. Not always but most times. While a break can be various lengths in measures, it'll always maintain the structural integrity of the form of the song it is within. Usually between one and four bars in length, these breaks give everyone a 'breather' in the flow of a song and a chance for the soloist to shine a bit brighter and set the tone for what is to follow. |

|

So depending on the musical setting, solo breaks can include everything we might imagine. From that one note 'honk', to the flashy, speedster 'light it right up' lick to the more 'formal' sorts of breaks arpeggios that outline the written chords of the turnaround, the improvised solo break has a very very special and exciting place in Americana musics. |

Consequently, solo breaks can bristle with giant energies that vault us to the top of the new chorus, re-energizing yet again the momentum of the group for the dancers. Breaks are usually one, two or four bars, depending on style and the shape of the melodic line of the song. For the way of the crafting of the melody into our traditional lengths of form shapes the length of the break. |

And to think it wasn't really too long ago that these 'breaks for silence' happened 30 or 40 times a night on a regular gig. Well a regular jazz or blues gig that is, although bluegrass, rockabilly and anything that swings really, makes it easy to add in solo breaks. For the harder the band swings the more 'pauses' it might need just to give everyone a chance to catch their collective breath :) |

|

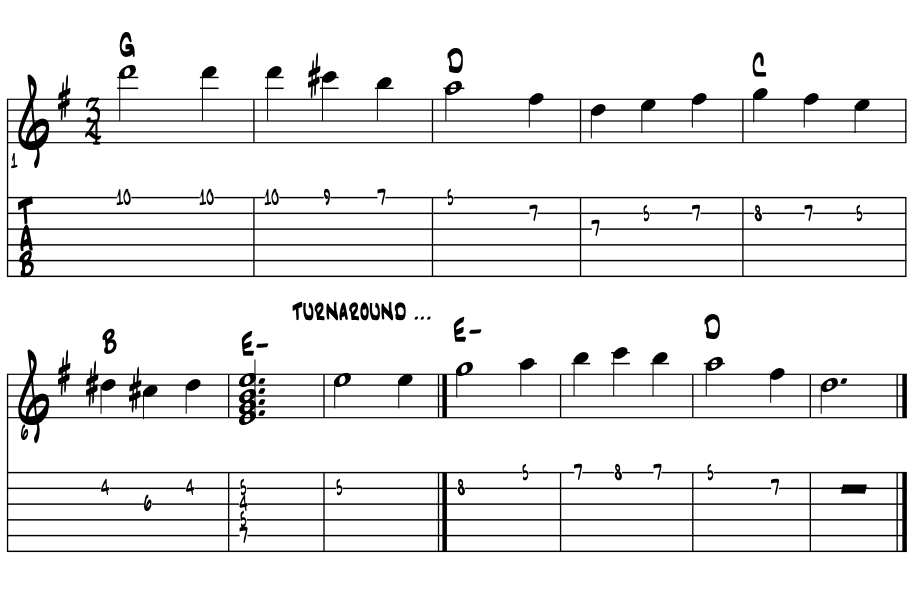

Back to turnarounds. So, thus intellectually 'solo break' empowered, we return to its common setting in our musics, the turnaround. These next ideas are the basic turnarounds we could find in our Americana musics. The presentation here is usually in two parts; the first is the harmony of the song's turnaround. The second is a realization of a single line 'solo break' melody for the harmony of that turnaround. |

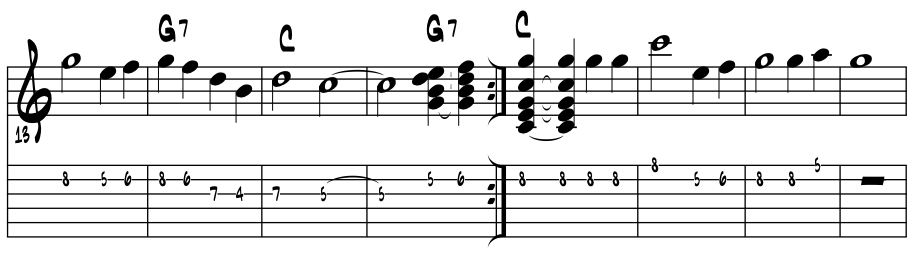

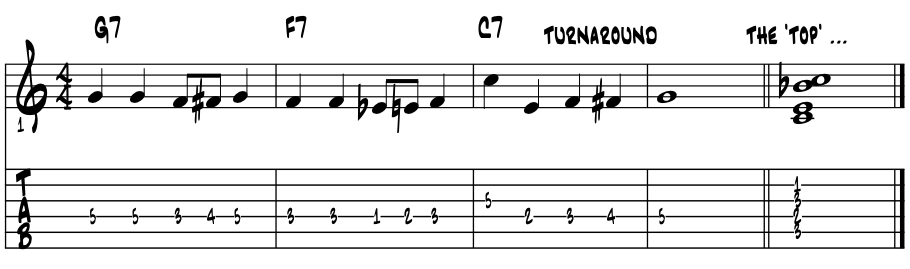

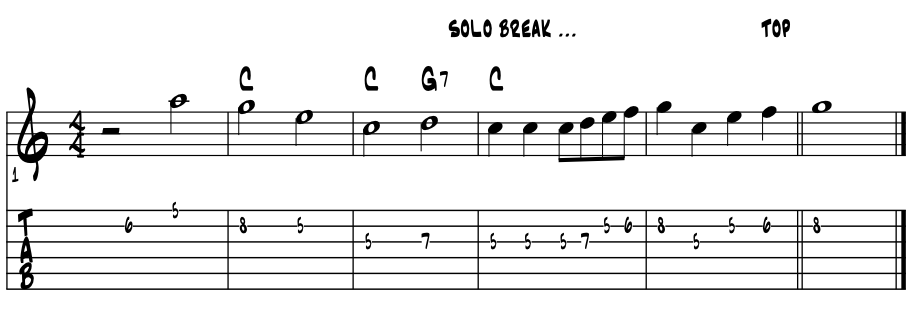

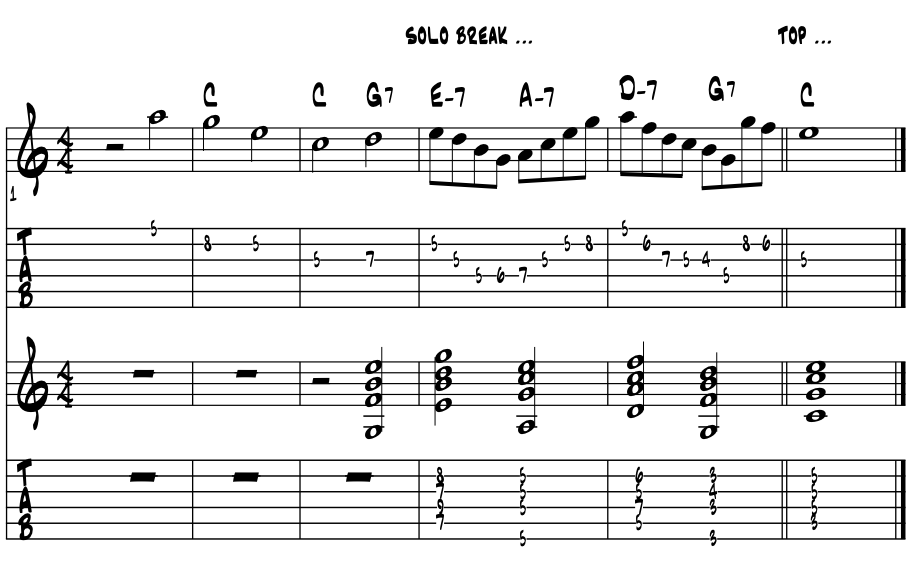

V7. This first melody, "Billy Boy" goes way way back in Americana. Here the written pick up notes become the turnaround melody line supported by V7. The repeat sign normally takes us back to the top, which in this chart is cut and pasted for playback right after the repeat sign. The turnaround chord is the G7 right in the middle of the graphic. The common V7 to I cadential motion. Ex. 1. |

|

|

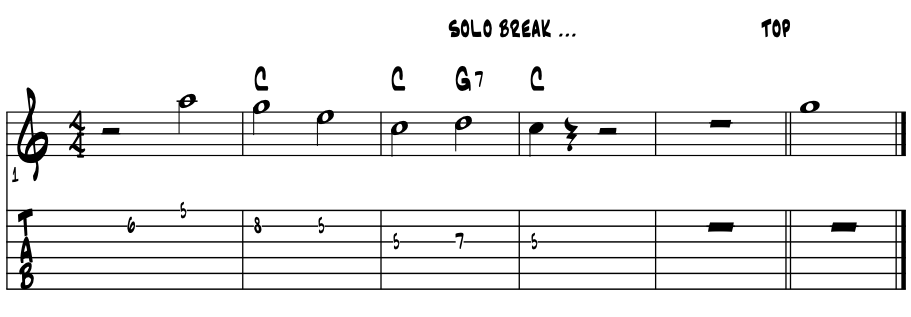

Solo break / one bar. This idea ends the melody as written and uses the one measure left over for the break. Note the written in 'picture' of the 'railroad tracks' to 'stop' the music in the fourth bar, to give the soloist the space for the break over the G7 chord. Slowed the tempo down a bit in the audio too from the example just above. So, just a one bar solo break in C for "Billy Boy." Example 1a. |

|

So just an ascending C major scale from G to G? A solo break we theorists could say was improvised 'over' the chord changes. Do shed this diatonic scaler styled 'launch' if just getting into this sort of thing. For scales work cool in soloing over the changes. Scales easily evolve into arpeggios which become the chords taking us to soloing through the changes. |

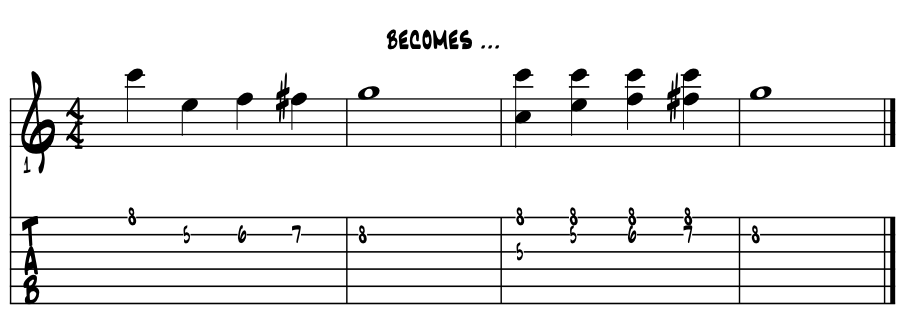

Two bar break. The two bar break is probably the most common throughout all of our styles. For with two bars we've a bit more room to figure out what to do, let a beat go by to find a start point etc. This next idea generates from a melody as old as the hills; "Greensleeves" seems so perfectly closed and balanced that it just starts again on its own volition. A true perpetual motion melody :) In the following arrangement no real turnaround chord, yet. Here is the whole last phrase of the song and the return to the top of the melody. Example 2. |

|

|

Solo break. Sound familiar? Cool. Now getting two full bars here, we add in a V7 chord and improvise a turnaround idea from the two chords and continue on with the first phrase of the solo. Example 2a. |

|

Cool? So, One and Five in a two measure turnaround? Yep. Most common turnaround chords, both written and improvised throughout all of our Americana? Could very well be. Learn it here and now if need be. |

Catch the two arpeggios used in bars 7 and 8 that clearly point and get us to the top for the start of the next chorus? Cool. The more vertical look to the series of written pitches, the arpeggios ... they 'launch.' :) |

Quick review. That's the gist of this turnaround / solo break theory for now. The rest is all art. The turnaround happens at the close of the form and gets us back to the top. If we play diatonically in the key of the song we are performing or arpeggiate the written chords, and synch up the timing of our break with the momentum of the band,we should be golden. Thus empowered, fear not the solo break, just prepare, relax and have fun with it. When your band can start and stop together on a dime, whole new possibilities open. When these are improvised with visual and verbal clues, a new level of fun and challenge begins. |

So is arpeggiating the pitches an easy way to 'hear the chord changes in the line' and keep things on track as we solo on 'through the changes?' Absolutely, and historically we have the recordings. So who are some of the 'arpeggio kings' of our Americana musics? |

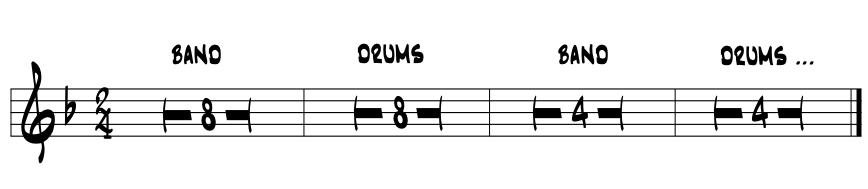

Trading fours / eights. Trading what? Fours. Four what? Four measures or bars ... if you prefer. Why? Well, its fun, a challenge, an opportunity to send ideas to other bandmates. Like a 'call and response?' Exactly, just a back and forth of ideas that each in succession tries to pick up one from another. Mostly done with drums in a blues / jazz setting, but any instrumentation works fine, we're simply creating a four bar idea backed with the band, then the band stops on beat one and the drums take over and respond with a four bar sort of solo. After their four bar solo, we then pick up on a rhythm of their idea and create a new four bar lick that we trade off back to drums. Back and forth we go, and everyone in the band who wants to gets a shot at it. Goes like this. Trading fours usually runs for a couple of choruses or so, it's a lot of fun and the audience really digs it as there's real clear lines to behold between the players and their thought process. With some players and bands, this is a rather exact science. And the stops and starts of the band and phrasing are meticulously adhered to. Total total precision as the band 'snaps' back and forth every four bars. The brighter the tempo, the groovier the snaps, the greater the challenge and risk to trainwreck. With so many of our musical forms being divisible by four, we can trade back in forth in most songs of any of the blues, blues influenced and jazz stylings we dig. Variations? Endless really. For we can trade any length of phrase really and on down the road we'll jazz it up by say; starting with trading eights, then half to fours, then halves to two and even down to trading one bar, which in faster tempos is a lot harder than it sounds, building up tremendous excitement. Although it is a near sure way to trainwreck the band, that can be fun too, especially the getting back on track as a band as all improv skills are on red alert to quickly right the thing. Even in this sort of boo boo audiences dig the humanity of the artists to bare and risk their skills under the lights. Here's a pic of a way to write out trading fours in a chart. Example 2b. ( or not to be :) Sorry, no audio. |

|

"You could be wrong a million times. You only have to be right once." |

wiki ~ Les Paul |

Blues turnarounds. These next turnarounds are as old as the hills, are two measures long and are woven deep in the Americana musical fabric. We theory label the first one here as the 'muddy' lick, for that's how it was taught to me, and many others, over the decades now. Named after blues master Muddy Waters, performer, composer and band leader of the 1950's and forward, Waters uses this essential blues turnaround exhaustively in his musics. And we all do really, once we learn what its universal mojo and guiding message means to each one of us as sentient, artistic beings :) |

|

While the pitches are generally the easy part; just a simple descending line with a touch of the blue hue and some chromatics, consistently fitting it into place in time is the tricky part; it can be slippery. In performance, it perfectly drives and directs everyone in the band, with really zero wiggle room as to where the music is going, so a ton of tonal gravity. For once the line is initiated we, all the band and folks in the room, we'll all be marching to the top for yet another go around :) |

So learn it here if needed for it can become the super solid basis of variations as well as confidently turn the thing around for everyone in the band, and in the room, in any situation and every time. So, works like a charm? Yep, like a charm with some global magic too. Globally too ? Yep. Always good to have a few of those right? |

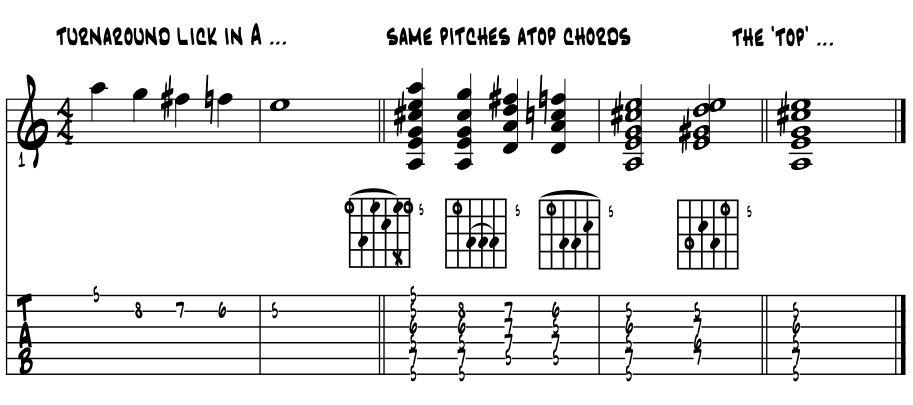

Here's the lick, our tonic pitch One down to Five, first as just the raw melody pitches and then supported by select chords. Thinking blues in A. Example 3. |

|

Sound familiar? Cool. No? Easy fix. Run it again and again till rote memorized. Let's flip this moon around and see what's on the other side. |

The flip side. We can flip this last turnaround idea over and create its own cliche so to speak. Both work the same way in the same spot in the music. So, a two bar, five pitch turnaround starting on the 'C7' chord. Hipsters here will note that while we're hanging around the same frets and pitches, we're in a new key. Example 3a. |

|

Sound familiar? Cool. "Rockabilly double stop." In brighter tempos this is a common jazz idea. Feels like there is some big swing on this side of the lick yes? For rockabilly leaning cats it makes for a nice, movable double stop idea from the now ancient 'blues and butter' scale shape. Example 3b. |

|

Everything is movable. These all move 'in soto' to any key center, and there's variations galore on both of these. They are classic turnaround bass lines too. Master the basics with Franz and the lick will naturally evolve to your own way of sounding it out. While never really out of place, though for some 'deep steeped' blues players both lines are too cliche sounding today. Master the originals first then move onto the new? So much of getting better at our craft is about relieving the boredom and finding the new. For starting with the old 'tried and true' can base the evolution of a creative artist forever. |

So there's some variance with this in the 12 bar blues form as the melody often resolves in the 12th bar, for 12 bar blues is also three / four bar phrases yes? So the last two bars of the phrase, the turnaround, is built right into the form. While we've no real official solo break and combined turnaround in basic blues compared to the other forms of songs, there are a couple of spots in the 12 bar form by tradition have the 'railroad tracks' styled stops creating a window of opportunity for coolness. |

In a 12 bar form. As the 12 bar blue form can be thought of as 3 / 4 bar phrases, the last four bars is where we set up the return to the top of the form for the next chorus. In the ninth bar there's usually a chord to set the turnaround in motion. On beat one of the 10th bar is probably tops of the common spots to stop the band. Surely when taking a tune out, ending a song during a performance, bands will cut at the 10th bar and negotiate the rest to the final hold. I've been in blues bands where this happens on every tune. Makes things easy so potentially more fun as the evening progresses and no one gets lost, ever :) And in bar 11 and 12 is where we're driving the motion back to the top of the form. |

Breaks are also common at the very top of the 12 bar blues form, a cut on beat one of measure one. We hear this in vocal numbers with a couple of verses to tell a story. Often called 'stop time', it gives a pause, a breather, a window for the next line of the story to enter and further the suspense. On the sounding of the Four chord on beat one in the fifth bar. A very common spot for the band to 'secretly' cut off a soloist in mid flight and see what happens ... 'make a horn player out of ya :) |

Jazz. As most everything else in our music theorizing, American jazz styles usually have the most robust versions and variations of any of our basic components. Tempos are fastest, melodies have the most pitches, chords can have all the colortones and stacked up in any fashion and still swing merrily right along. Same with the components of the turnarounds and solo breaks in jazz? Pretty much. There's a famous one from a 1940's recording session in NYC by Charlie Parker that was so outrageously cool that the band missed the entrance back in. And when you're recording on to wax ... that's a real boo boo :) But it's captured and out there in sound and transcription somewhere, explore search find. |

|

Where to start? Might as well pick up where we last left off with the melody closing in on One to resolve followed by a V7 chord to return us to the top of the form. So what we do is simply add in chords between these two; the One and Five chords, to 'jazz up' the chords of the turnaround and give the soloist more to work with creating a solo break. |

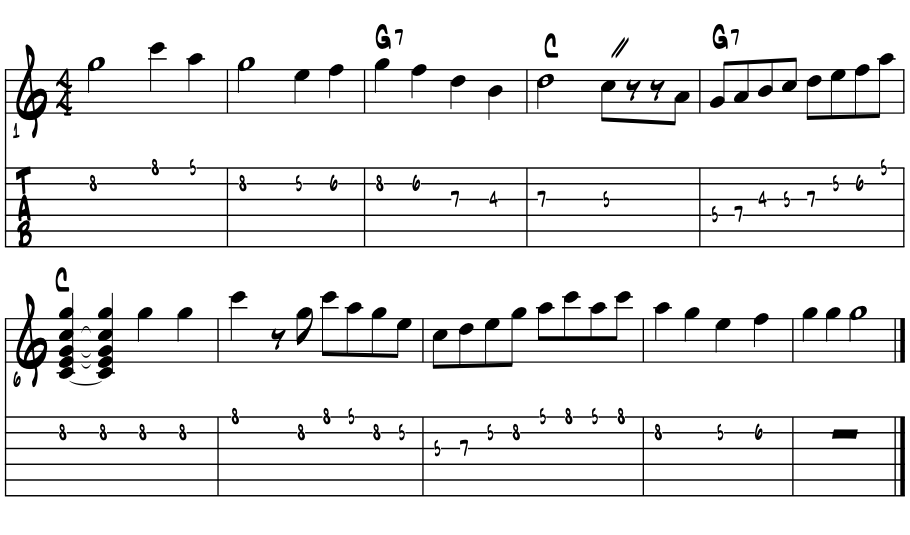

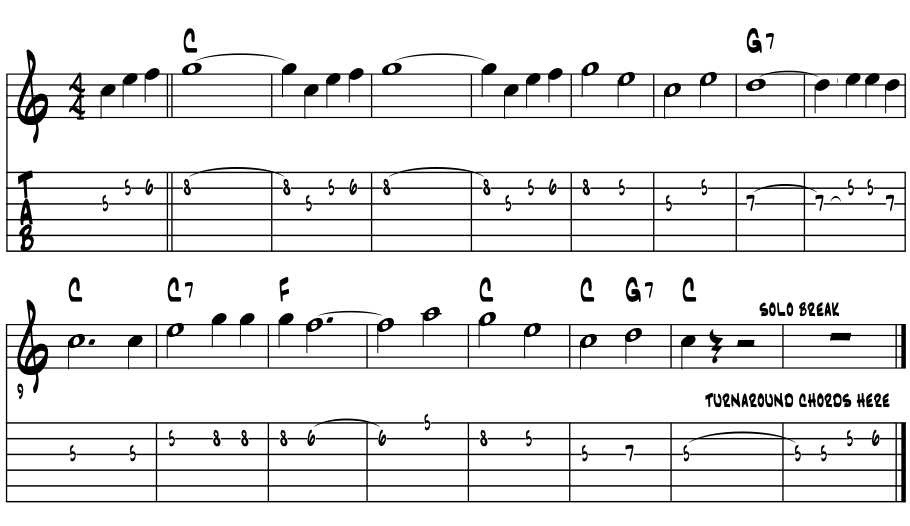

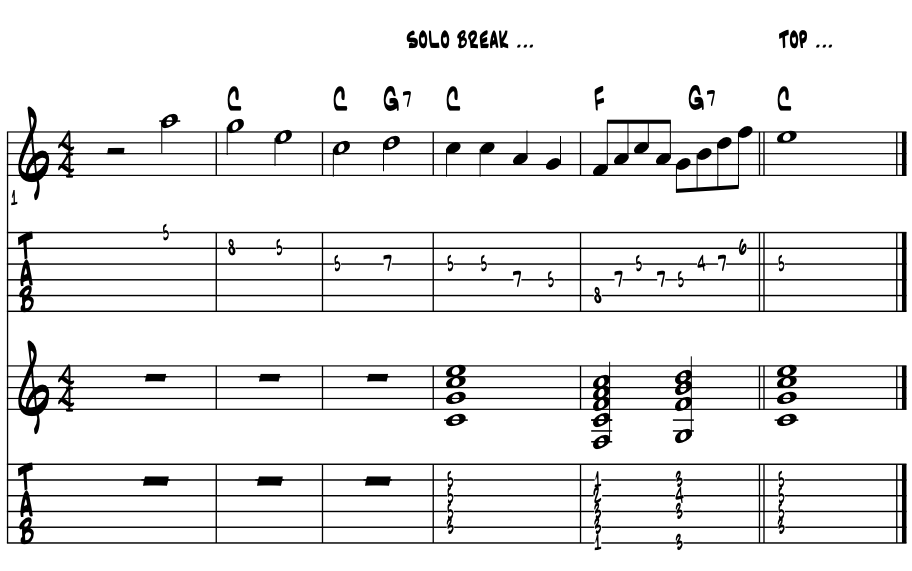

'Jazz up' the chords. Using the last measures of the our gospel song "When The Saints Go Marching In", we'll start with One and Five and create the diatonic theory to get us to its Three / Six / Two / Five chord progression; a top choice for a standard jazz song's turnaround, which chock fills up the two measures we usually get. Starting at the beginning, here's the whole melody. Example 4. |

|

|

First evolution. Now let's extract the last part of the phrase to focus on the turnaround / solo break, setting up the return to the top. We'll use this format for the rest of the examples which follow. Example 4a. |

|

Second evolution. Adding in an improvised line for the solo break. Slowing the tempo down a bit for clarity, these break pitches are the diatonic C major scale. Example 4b. |

|

Third evolution. In this next idea we slip in some blues hue and a V7 chord, arpeggiate its pitches to jazz up the break. Example 4c. |

|

Fourth evolution. In this next idea we slip in the Four chord before the V7 chord, arpeggiate their pitches to jazz up the break. Example 4d. |

|

Fifth evolution / Four becomes Two. In this next idea we morph the diatonic major triad of the Four chord (IV) into a Two chord (ii-7), with its minor triad and added 7th. To create this we simply slide back one pitch in the diatonic arpeggio; so D becomes the root under the F major triad. All diatonic, the 'sleeker' Two seems to better handle the brighter tempos, thus sounds more jazzy in many cadential settings. Examine the evolution of the pitches by letter name and then aurally. Ex. 4e. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Four |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

F |

A |

C |

Two |

. |

. |

. |

. |

D |

F |

A |

C |

|

Two / Five / One. The Two / Five / One cadential motion in the last idea is a game changer for many. For while the Two chord is common throughout our styles, once the 7th is added and it pairs with Five, it becomes a sort of 'tension cell' capable of taking us to many destinations beyond its own diatonic directions. |

Another evolution with 251 is through the V7 chord. We add b9 to the chord which creates a fully diminished 7th chord from the major 3rd of the chord. As each of these four pitches can be a leading tone, thus we gain four resolution options to four parallel key centers through this theory and basic chord substitution process. |

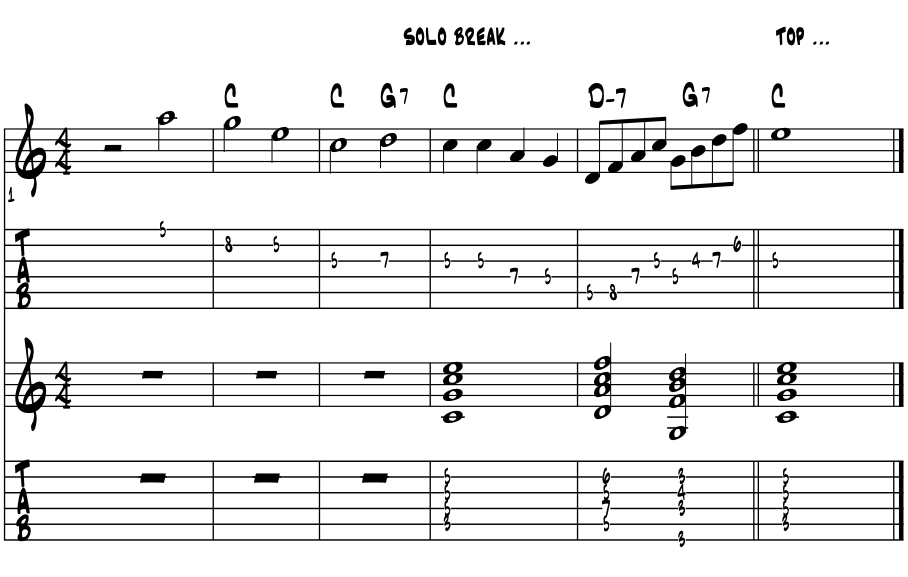

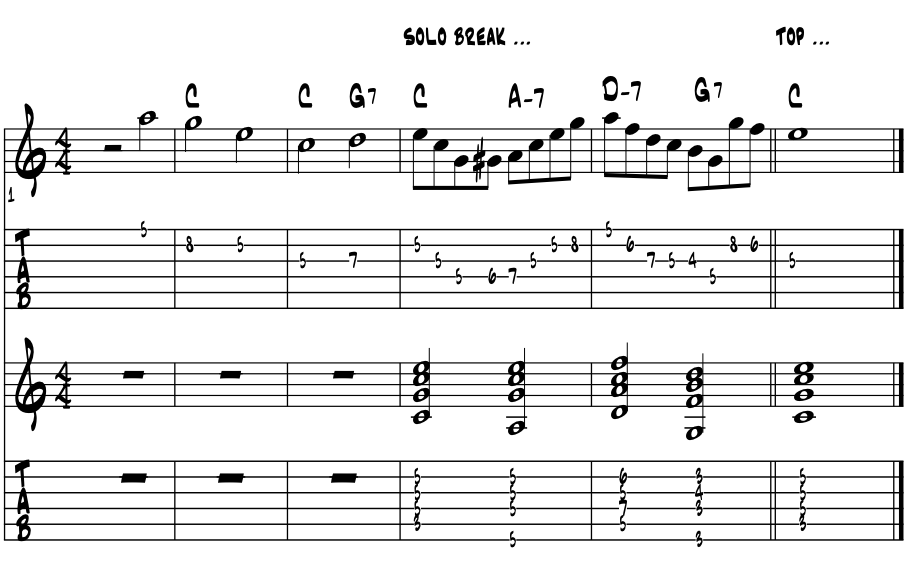

Sixth evolution / relative minor. In this next idea we can create some variety by adding in the relative minor 7th chord after the tonic chord. This is the same pitch theory as applied to Four into Two; just moving back one note in the diatonic arpeggio to make the new chord; One becomes Six. Please examine the evolution of the pitches by letter name and then aurally. Example 4f. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

. |

. |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

. |

. |

arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

. |

. |

One |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

Six |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

G |

|

Feeling more jazzy? That accurate arpeggios will tell the harmonic tale every time becomes indispensable to the jazz artist that loves to run the chords, an improvisation technique thought to have originated with the 1939 recording by Coleman Hawkins of "Body and Soul", which today might the most ever recorded pop song. Remember that back in '39', what we know of today as jazz was the pop music of Americana. |

|

Seventh evolution. In this last idea of this discussion thread we now replace our tonic chord again by moving one pitch in the arpeggio but this time in the other direction. Please examine the pitches. Example 4g. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

One |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Three |

. |

E |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

So we're replacing the C major chord with an E-7. In doing this our cycle of chords does not resolve as we are moving from V7 (G7) right to Three (E-7). Seem a bit radical? Well one thing to consider is in most jazz harmony, every chord has a 7th, and oftentimes other colortones as well. In this case our pitches would look more like this. Example 4h. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

I maj 7 |

C |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

iii -7 |

. |

E |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

Cool? Kinda lights right up :) Now we have a full minor triad to work with. This basic shifting of one pitch either way of the diatonic arpeggio accounts for a lot of the harmony variations we enjoy in jazz. So what we've created now is a cycle of perfect fourths; 'E A D G which resolves to C', a Three / Six / Two / Five / One turnaround, to get us back to the top of the song. This four chord grouping and motion is very common in the literature, not only as a turnaround but also within the written chord progressions of songs. See if you can recognize it in the following music. Example 4i. |

|

Cool? So with a bit of the theory we create more challenging options for the turnaround and solo break. That all of this is diatonic makes the pitches easy to find and the motions clearer to hear. From this diatonic basis there are jazz evolutions that really know no bounds. This progression; Three / Six / Two / Five, written into "Body and Soul" in the bridge, becomes in succeeding generations a boilerplate template for evolutions, for we see it time and again in many forms and with varying degrees of tonal gravity and aural predictability. |

Author's note; this chord progression did not originate with the writing of "Body And Soul" and goes way further back in our history. I'm hoping to find its source in a new book; The Evolution Of Harmony In Americana Music, from 1860 to 1960. |

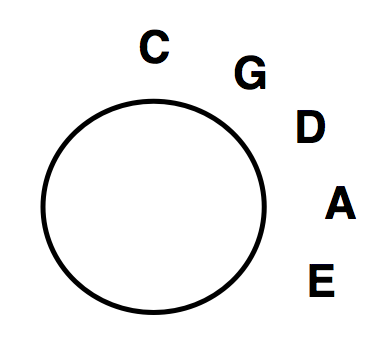

Cycle of 5th's and 3 / 6 / 2 / 5. In the discussion titled 'silent architecture of the pitches' we discovered the cycle of 5th's. In this cycle we arrange our 12 pitches of the chromatic scale in intervals of a perfect fifth. Our progression under discussion here is a cycling 'back' or 'backpedaling' in this cycle; a counterclockwise motion. Here is an abbreviated cycle of 5th's with the roots of these chords with C at the top designating key center tonic pitch. Example 5. |

|

3 / 6 / 2 / 5 / 1. So in the key center of C major, where the pitch and letter name 'C' is One, we simply measure diatonically these pitches which become our scale degrees. Example 6. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

So in creating any sort of relationship between pitches, especially when one pitch has been chosen as the tonal or tonic center, these sorts of numerical representation are projectable onto any grouping of our diatonic scale. Once established numerically, with some steady study and rote memorization, any of our 12 pitches can become One, from which all others are then measured and numerically identified. The gist here is that we can learn any one theory rule and apply to any one of our 12 pitches. Super super handy for those who learn the numerical magic of our ancient system. |

Review. Knowing the basics of the turnaround and creating a solo break become important skills for the modern guitarist. Having been referred to as the 'meat' of the improvisation, strengthening and eventually mastering these components in our music allows for good starts (solo breaks) to our improvisations as well as our ability to string choruses together by confidently getting through the turnarounds, creating longer solos to better enjoy the artistic potentials this can bring to all involved in our musical creative processes. |

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"Life is about creating yourself." |

wiki ~ Bob Dylan |

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |