|

Nutshell ~ style / genre / number of pitches / melody. The following discussion attempts to correlate styles of music and theoretical complexity; so if we can keep in mind that at one point in our histories that 'jass / jazz styled musics' was once America's premier 'pop music' (popular music), we inherit both a rather vast collection of songs, and through their study, a fairly clear pathway of learning music theory. As jazz music anchors one end of our style / complexity spectrum, all of our other styles of yesterday and today; various genres of folk, blues, rock and pop fusions, can theoretically lean towards jazz, as we discover ways to 'jazz up' any song in any style, create something new and fresh, and do your own thing. |

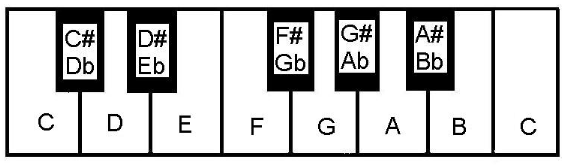

Jazz and blues. Historically speaking, the jazz library of songs and their compositional theories has included in some shape or form similar theory elements that are found throughout all of 'AmerAfroEuroLatin's styles / genres. Bottom line; all styles are based on the original 12 pitches. And in Americana musics, the early folk ~ blues songs are the roots. For jazz even ? Historically, for certain :) Cool ? |

So, the music you dig; can you broadly describe and define it within a style or genre of ? Are you leaning to folk, the blues and funk ? Or leanin' more to rock ? Classical or pop or hip hop ? Or leaning towards the original delta blues and forward through to the wizardry of bebop then on into the river of the ever evolving 12 pitch mashups of jazz ... ? Got a 'describe word' for it ? Cool. Need a word for it ? We got 'em. |

For in following along this learning path, by having a word or two description of style we can find you a starting point into this e-curriculum's weaving of music theory and its history, sparked into life by defining a style by word and then looking at the group of pitches (and the number of different pitches in the group) that generally creates the melody of songs in the style we dig. Once we're melody cool, chords usually follow and then put things into motion by moving through time. |

Doing some math. So, ever see this sort of 'style spectrum chart', to outline the theoretical perspective of a gradually increasing numerical complexity of the pitches while evolving through our spectrum of Americana styles ? Example 1. |

musical style |

om ~ blues |

kid's folk blues gospel

bluegrass rock country pop |

jazz |

# of different pitches |

1 2 3 4 ... |

3 4 5 6 7 8 ... |

7 8 9 10 11 12 |

So the way this works, in theory, is to pick a melody in a style and then count how many different pitches it takes to create this melody. Generally speaking, it turns out that there's more than just a casual relationship when thinking about melody and which pitches it needs to bring its magics; 3 note blue line, 6 notes for gospel, 5 notes for a kid's song. Which five ? Or three, four and six ? How about a melody with nine different letter name pitches ? Leaning us to jazz ... ? Why might this be important to the modern theorist ? |

Thus empowered, we as theorists will see a couple of benefits. First is the evolution of our melody color by adding one pitch at a time to enlarge the pentatonic group of five pitches. This become a basis to 'bluesify' or 'jazz up' our ideas. And second, learning a melody with a set of define-able pitches, say a major pentatonic group with an added perfect 4th, can land us squarely in the gospel style, a mood we might want to create during an improvisational solo. Setting such 'pitch limits' might make for new ways to solve old puzzles, as 'less' is said to be sometimes 'more.' Knowing we only get 12 unique pitches in total, we can create a sort of spectrum of style, simply based on the number of different pitches that were used to create our melody. And since in pure academia BA level formal music school theory we learn of these 12 possible notes, this theory discussion of a style spectrum can go rather quickly from this most numerical of perspectives. |

One note at a time. When we get down to the roots of early Americana blues, we learn that one pitch easily tells the tale. And surely in today's spoken word stylings, one pitch is often enough for their storyline, motored by the unique rhythms of each individual artist. With two, three and four pitches, we find the two note 5th's of shred metal chords, three note for triads, four notes brings a super solid blues elevator in minor, 'b7 1 b3 4' notes of a minor key, and of course the perfect balance of Coltrane's gem of four notes / in major, '1 2 3 5.' (Author's note. Historically, we've just spanned near a hundred years of our music history with blues and jazz and still have eight more pitches to go.) Folk songs? Five and six pitch melodies mostly. Gospel? Six pitches in major is "Swing Low Sweet Chariot." It's pure sentient sincerity unmistakable in our hearts. And six pitches in minor gets us right back to the super Americana core of it all; the blues group. And with bending notes, deeper into the blue heart of the matter, we can slip a blue's hue's vibe into the melodies of our stories, songs, and styles. And from there ? Seven pitches and we be into the diatonic realm, so both a melody and chordal super kaboom. Beyond seven? Eight and nine pitch melodies and we're well on our way towards the 12 tones of the jazz stylings, genres, vamps and grooves and beyond. So which one, which One pitch and why ? What are the two or three note groups of pitches ? Is there a set group of four notes ? Surely for five pitches yes ? Six pitches major ? Six in minor ? Yep. And seven letter name notes for the diatonic relatives, the seven modes, all the arpeggios, chords and beyond. Eight ? Octave closure with eight pitches yes ? And then beyond, to groups of pitches with '9, 10, 11' and to '12', the chromatic scale. So thinking of your style-wise choices, how many different letter name pitches are in your melodies ? |

And rhythms. Crazy but true, that shaping styles of music by rhythm can always ring true. For a 'C' chord is a 'C' chord, mostly, and yet how we set it in motion ... is what brings the style magic of music to life, to tell our stories, with flavors from all around the world, requires the right rhythms :) So in a sense, the rhythm becomes the 'setting' for the story. We just jazz it up with words and melody notes, chords and a bass line story. So our learning here, along with groups of pitches, involves getting some 'rhythms styles' in our souls and under our fingers as well. Other number correlations ? Beyond this discussion of number of pitches we can examine the number of chords, rhythm patterns, sequential patterns, number of measures and form of all our songs. For these all want to correlate towards understanding the music theory principles within musical style too. And while there's artistic exceptions (endless :), there's a truth be told in this numerical perspective that shapes and organizes our understanding of how the Americana spectrum of styles can morph through from one to another, simply by the addition or subtraction of pitches, and understanding the aural colors they can create. Thus ... the basis of 'jazz it up' ... ? Indeed :) Read on ! |

Making melodies. So we theorize our musical styles in the following discussions by examining, pitch by pitch, the 12 unique notes we get. Initially working from one fundamental pitch, and following the overtones series, one by one we add the 11 remaining pitches. At each step we create links into the music theory we associate with that number of pitches. In building up our chords, to stand alone or support a melody, through the last 200 years or so, we nearly always rely on the 7 pitches of the diatonic scale, seven pitches paired for both major and minor key melodies and chords. So even if the melody is just a couple of pitches, we still need all seven diatonic pitches to create its chords. Even songs of just 'three chords and the truth? Yes, even with just three chords, we need seven unique pitches. In 'G' major 1 4 5 triads; 'G B D, C E G and D F# A.' Need seven of the 12 pitches; 'G A B C D E F#.' Relative 'E' minor 1 4 5 triads; E G B, A C E, B D F#.' Need seven of the 12; 'E F# G A B C D.' Cool ? The 'relatives' yes ? |

So with each added pitch we evolve our music and its various styles and genres. And once there's a handful to work with, we begin to sense the merging of styles, one into another, and along the way create this e-book's philosophy of a modern guitarist, of how with a nick of a pitch here, or a passing tone there, we can flavor or jazz up in our own unique ways whatever might come along. |

|

A spectrum of style. We've 12 total pitches for sure and half a dozen or so broad style categories, add in genres and there's a ton more combinations. Thus, the following left to right visualization emerges. Example 1. |

musical style |

om ~ blues |

kid's folk blues gospel

bluegrass rock country pop |

jazz |

# of different pitches |

1 2 3 4 ... |

3 4 5 6 7 8 ... |

7 8 9 10 11 12. |

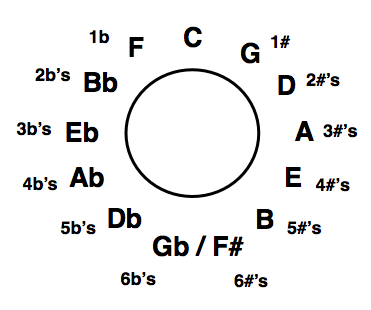

All we get. In theory we get just the 12 unique pitches. As our theory is based on nature and the natural ordering of the pitches, we use a core five pitches to create the major and minor pentatonic melodies of children's songs and folk music. Add a very special sixth pitch to the pentatonic minor and we make the blues hue. Add two select pitches to our core major five creates the seven of the diatonic scale, which some believe to go all the way back in our histories which when equal temper tuned, fully enables all the chords on a piano. Add another pitch or two as chromatic passing tones to seven enables a blue's hue into well crafted pop melodies and cadential motions into various common cycles of chords. And in jazz, well all of the 12 tones are of course in play; in any tune, any time and any day :) |

In performance. Performing songs in the Americana styles is nearly all the same in respect to one crucial aspect. That all through the clubs and tonks and restaurants, from dive joints to stadiums, and nearly through all the styles, the performers are playing from rote; they've memorized their parts. And when presenting their art and moving through time as a band, eye contact among the bandmembers helps to make the magics happen. Termed 'line of sight', which combines with paying attention, everyone in the band gets a chance to contribute to the mix, create and catch special moments and get to the final hold together :) |

Melody pitches of styles. So, want a hint of blues in your folk sounds? Maybe more of a jazzier bop in your pop? Find a deeper swing feel in your home spun bluegrass or a more rockin' feel to your country core? Then by all means read on here as we go 'pitch by pitch additive' to rote learn tried and true ways to evolve most any melody or song with just a flick of a pitch or two. |

While there's lots of theory aspects to each of our styles, the following discussions centers on melody; and specifically, the number of unique pitches we commonly use to create melodies in each broad style. |

Making loops. Once we choose a 'set number of pitches', and make them into a loop, we can then determine what harmony is diatonically available to support its melody lines. From this basis we can begin to auralize a linear spectrum of musical styles reflecting the number of pitches generally used to create them. In doing so we'll each find our ways to morph from one style to another. Make folk melodies into jazz songs an vice versa, add a bit of blues wherever and whenever, opening up new potentials of the artistic 'mix and match.' |

For example, traditional Americana folk music rarely if ever features any sort of true chromaticism. While on the other end of our style spectrum, the jazzers often embrace a full range of half step motions from either direction, thus utilizing all of our 12 tones as upper and lower neighbors. Please examine the general number of melody pitches grouped by musical style. Example 2. |

total # of pitches |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

1 ... |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

children's songs (5) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

(A) |

. |

. |

C |

folk and country (6) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

gospel (6) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

blues and rock (6) |

C |

. |

. |

Eb |

. |

F |

. |

G |

. |

. |

Bb |

. |

C |

pop (7) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

jazz (12) |

C |

C# |

D |

Eb |

E |

F |

F# |

G |

Ab |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

~ folk ~ blues ~ gospel ~ country ~ rock ~ pop ~ jazz |

Moving left to right. So moving left to right in our chart, as more pitches come into play, we've simply more options to shape our melodies and harmonies, thus the general style of music we're creating 'evolves in numbers' of component parts etc. Move right to left. The flip side is true too yes? Moving right to left, that as we reduce our number of pitches, we can often increase our sense of tonal center and aural predictability, tonal gravity increases as we center closer to one pitch. |

Styles; and for the chords ? Creating the chords to back the melodies is a bit different. For if there's more than one chord in a song, and there usually is, the theory says we'll need more of the diatonic pitches of the song's key center to build them all up. But correlating a music style with the number of pitches in a chord, as used in song to create that musical style, well that's a new story and a way to think along this perspective; the fifth's of metal (2 pitches) folk and rock triads (3 pitches) add 7th's for the blues (4 pitches) add color tones for jazz (4 or more pitches) Example 3. |

|

total # of pitches |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

1 ... |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

metal (2) |

C |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

children's songs (3) |

C |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

folk (5) |

C |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

Bb |

. |

C |

blues and rock (7) |

C |

. |

D |

D# |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

Bb |

. |

C |

pop (9) |

C |

. |

D |

D# |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

jazz (12) |

C |

C# |

D |

Eb |

E |

F |

F# |

G |

Ab |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

Roman numerals |

I |

#i |

ii |

#ii |

iii |

IV |

#iv |

V |

#v |

vi |

bVII |

vii |

VIII |

|

| Ah ... the evolutions of the harmonic colors as we morph through our styles :) Begin to loose the sense of 'Kansas' towards the close of the line? That's part of the magic of jazz; the essence of tonal gravity and its ability to project a predictable artistic direction begin to fade, eventually ascending towards the chromatic blur and beyond. |

In most any style ... In today's wide spectrum of Americana styles, the seven pitches of the diatonic scale are the basis of all of our chords. For even if there's just a few pitches in the melody, chances are the song will 'go to Four' at some point and we'll need another pitch or two more to build these chords. Rule: we need all seven diatonic for One, Four, Five chords in a key center, major and minor chords. Also, the chances are good we'll never hear a sharp nine (#9) in a song for kids, or even folk tunes for that matter. Except maybe in Halloween songs :) But as soon as the blues hue kicks into any sort of folk styling, and we move towards a blues styling, good chance the #9 color tone might want to arrive somewhere in the music, even just for one beat, add that extra oomph ! |

|

Quick rote review. So this correlation of number of pitches and musical style is simply to place each of our 12 pitches somewhere in the fabric of our weave of musical styles. To develop a sense as musicians of what generally hangs with a genre. For pro leaning cats who want to gig and keep the gig, knowing what is appropriate, and when it is, often becomes a foot in the door of showbiz. Thus aware, we become empowered, energized even, to search to find the (new) colors we need to tell our tales, in any style, or to shade things a stylistic way when needed; bring a quick smile, a sorrowful moment, brighten it up with some sassy :) |

12 pitches. In this next chart of our letter name pitches, please examine the seven diatonic pitches in relation to 'the other five.' Example 3a. |

. |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

diatonic chords |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

other five pitches |

. |

Db |

. |

Eb |

. |

. |

Gb |

. |

Ab |

. |

Bb |

. |

. |

Easy enough yes? The tricky part in all of this is simply to be flexible in our thinking, yet somewhat rigid to preserve the diatonic perspective throughout. 'Diatonic' is our theory 'line in the sand.' So how do we keep all the theorizing straight? Think diatonically and from the root of the chord ? Yep, thinking from the root of a chord, within the diatonic key center where we find it, will keep things groovy, works like a charm, every time :) |

Quick review for chords and style. Once an artist can think of and name, spell out the letters of each of the seven diatonic triads, and know the five pitches that are 'left over', which become the colortones for jazzing up the seven triads, that's really the whole tamale, diatonic deal for the chords. |

It's all in a song somewhere. The rest of this 'music theory / music styles lesson' is to go on and explore and learn songs and tunes, finding cool new bits of melody, a chord or progression, a bass line story that you don't already know etc. Extract, examine to understand its theories, and shed. Then ... And historically speaking, by teaching your knowledge to other interested souls, i.e., the band, and near every time, seals the deal of our own understanding about the music theory of spelling triads / chords. If needed, here's the essential triad spelling chart in 'C' major. Rote da commencia :) Example 4. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

major scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1/2 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V7 |

vi |

vii- |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEG |

DFA |

EGB |

FAC |

GBD |

ACE |

BDF |

CEG |

Advanced studies. Already hip to all this, then as time permits, run and rote learn these melody and chord theories through the letter names of each of the 12 key centers and grasp the whole tamale. Get these pitches under the fingers. Total rote. Jazz leaning guitarists should consider to further explore and to rote up the interval and arpeggio studies from each of the five movable scale shapes. Add in the concept that we can slip in all sorts passing chords, that live between the diatonic steps and we're pretty much theory golden. These we often discover when learning and playing songs. Finding a new twist on the same old same old :) Advance this even further to know the leading tone / substitution properties of the fully diminished 7th colors, and discover the penultimate steps to reach the Americana harmony nirvana. |

Here's a jazz style version of the chord spelling chart that starts this all off. Note in this organization, that we've gone beyond the '1 3 5' of the triads and added one more, the diatonic 7th for each position. Theory wise, this in itself is a stylistic and super theory game changer, all simply depending on the art you want to create. Example 3b. |

scale # degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C major arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

chord # / quality |

Imaj7 |

ii-7 |

iii-7 |

IVmaj7 |

V7 |

vi-7 |

vii-7 |

VIII |

diatonic 7th chords |

CEGB |

DFAC |

EGBD |

FACE |

GBDF |

ACEG |

BDFA |

CEGB |

arpeggio # degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

color tones |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

Cool? By simple addition of one select pitch, in this case the 7th for each diatonic triad, our theory kabooms as our potentials for a 'chord type' now looms. Along the road, fill in the pitches of each of the 12 major keys at least one time during your studies. We just want to get our arms completely around the topic. Even doing this one time will put some light on things, might not ever need the key of 'Gb', but then way easier to find if we ever do need it. |

With most of our Americana styles, a capo covers the guitar's ventures towards the remote key centers, but one never knows where that long sought puzzle piece will be found, sometimes in between the ones we know, so ... After running the 12 keys through this chart, and again, even only once, or twice, and chances are you'll be on the pathway to becoming both a chord spelling wizard and thus, a potential lounge lizard :) Jazz leaning on your art's compass ? Learn this chart, learn this chart ... with as mucho thought lightning as musterable :) Example 4. |

|

Note values, rhythms and syncopation of styles. Yea the same sorts of 'numbers of rhythm notes and musical style' correlations seem to hold. Thinking left to right of our visual spectrum, mostly whole and half notes, so one and two notes, for our songs for the kids. At Four we've the quarter notes which gets us to 4 / 4 time, really the Americana essential time signature, as most of our music has four beats per measure. Quarter notes creates the walking bass line stories, so common and essential in all our musics. Three quarter notes per measure, 3 / 4 time. While we skipped three in the chart above, we know that three notes grouped together brings the magical triplet, the rhythmic figure that helps spark off the swing. And there is 'waltz' time, common as 3 / 4, which includes near anything 'in 3', counted '123-123.' Example 4a, feel the ' 1 2 3 1 2 3' of a jazzy 'waltz.' |

'1 and 3 or 2 and 4 ? For the folk rhythms, usually pulse on beats 1 and 3. When we gain the backbeat of 2 and 4, we're heading towards the blues and into rock. And while rock hits on beat one, there's usually a 'snare pop' on 2 and 4. The basic beat numbers of the 'country, pop, rockin' metal styles' can all fit right in around here too. As we begin to add in more improv, the 1/8 note, and long streams of the eighth notes, becomes the basic rhythm for bluegrass and on into jazz soloing. Then into 16th notes for the shredders. |

|

Styles / rhythms. Seems crazy but true, that shaping styles of music by rhythm can always ring true. For a 'C' chord is a 'C' chord, mostly, and yet how we set it in motion ... is what helps to bring the style magic of music to life, to tell our stories with flavors from all around the world. So in one sense, the rhythm becomes the 'setting' for the story. We jazz it up with words and melody notes, chords, a bass line story and arrangement. So our learning here involves getting some 'rhythms styles' in our souls and under our fingers. Keep this in mind as the following learning pathway unfolds as the concept of 'groups of pitches' helps define and shape style and genre. Dig these rhythm patterns of styles in four bar loops for starters and work to get them under your fingers by ear. Start by clapping / tapping along and finding the pulse to start counting along. Example 1. |

|

techno dance |

pop rock |

16th notes |

country gallop |

jazz 1/8 note triplet |

Superhoot pop riff |

1& 2 3& 4 |

Your musical style. So what's your style of music? Been looking to your own natural world for inspirations? Have a folk tale to tell? Searching for the blue notes? Got some country picken' to do? Making the big roar of it all with rock and roll? Looking to write pop hits for the radio? Maybe you dig conjuring up cool jazzy grooves and instrumental takes on anything with a melody? Using dance vibes to back up your spoken word vocal tracks? Knowing the theory is a way to morph and draw from them all, creating a full palette of the musical colors from then which to paint your stories of life in music. |

So in the following discussions, the weave is all about finding musics that we can create with a set number of pitches for creating melodies, rhythms, styles and genres. Once initiated, the cross pollinations of ideas between the best flowerings of each of our styles is maybe just a breeze away. |

~ so ... what do we get with one pitch ? |

Musical style by number of pitches. What follows is probably more fun and musings than serioso theory, yet we do get to explore and combine our core philosophies; namely, how the number of different pitches in scales and chords, in our melodies and rhythms, reflect and shape the sounds usually associated with a musical style. Based on the overtone series, and possible 'stgc'er for some readers, 'styles by numbers' simply illuminates the common musics created with a given number of elements. And then as we add in new pitches, sense our styles morph from one into another. |

Starting with just one pitch and working up to include all 12, we create a survey of the styles and in doing so, create a perspective of our resource that can give us insight to shape and advance our own journey and help advance the journeys of others too :) |

One pitch / drone tones and pedal tones. So, what musical magics do we get with just the one pitch? With one pitch, we can create a pedal tone, a long sustained note woven through the mix. And some instruments just create one pitch too. What music comes from any one pitch that such an instrument creates ? A didgeridoo ? Indigenous. A triangle ? In theatre, one note with lots of ways in. A drum ? well, that's where our 'one note sambas' all started yes ? In meditation. We can bring forth and sound one note from within ourselves, to help find ourselves and focus to create and grow our intuition strengths through a meditative process. Ever hear of 'Omm ... ?' The magical place of 'Om' is usually found in one note, and lower pitched towards one's bottom chakra, that we resonate around in our cranial cavity, that we listen to or sing ...

So a long, musical note that collects our thoughts to one focus point, in a self induced meditative state. How cool is that ? Now ancient with a global reach, the one pitch 'Om' has been a part of our spiritual process universal forever. Here pedaling guitar along on our lowest 'E.' Example 5. Om ... om ... om ... om ... :) |

|

|

Do we get this magic with any one pitch? Sure can. Any of the 12 different letter name pitches ? Yep. Remember, 12 is all we get, so for our Americana styled melodies supported by all and any chords, we be good :) Still, we'll just need one pitch for the 'Om.' Modern vocal musical styles. There's a real trend in melody these days toward one note. One pitch, repeated into rhythms which power the rhyming of words; so hip hop, rap and beyond yes ? Spoken word with one note and solid rhythms, not quite the jazzy 'scat singing' of yore, but in this historical light, not completely new either, just the new ways forward :) |

Two pitches / 5th's of modern rock. With two select and unique pitches, our first 'silent evolution' beyond the octave, and following perfect with our organic overtone series too, we get a ton of style coolness with a root and 5th interval. As the first different pitch in the overtone series, we use to base our silent architecture, which corralled into its own 'cycle', creates the cycle of 5th's. Fifth's, sounded loud, generally command attention, of now ancient heralding of royalty from all the way back forward to today as guitarists, we've a new herald of overdriven, crunchy 5th's to light up any room. For with our modern electronic wizardry and gear, with just moving these two paired pitches around, these '5th's of modern metalists call yet again to a new generation of royalty. So not too bad for just two pitches eh ? Ex. 6. |

|

Three pitches helps make every style in the book ! With just three pitches we create the strongest of our components; the triad. A colossal in many ways, here we think melodically and pair up the vocabulary word 'triad' with a three note melody. Example 7. |

|

Attention ! :) Sound familiar ? Cool. Our national anthem melody is pure triad based. Great vocal song for chops builder and super high profile gigs :) Click off to rote up on the rest of this line. |

|

Three pitched chords ... triads are in all styles. And with the three notes of the triads sounded together as a chord, our styles of Americana musics all take on many new dimensions. ~ a 3 note chord is also 'theory known' as a triad ~ And while we've had the pitches all along, stacking them into chords is a fairly recent invention in the evolutions of our combined AmerAfroEuroLatin musics, 400 years or so now. Building from our root pitch 'C', here are the four different three note triads / chords we get from the diatonic realm. Example 7a. |

|

Sing along. Can you sing along and find the different pitches for each triad? Try again. And again ... if needed that is :) Master these four colors and take a giant step forward. Note that we moved the last shape up an octave to make for an easier fingering solution. |

Four pitches core the blues. Back to styles and pure melody, with four select pitches to work, we can more fully include both major and minor tonalities. For with four pitches we can span style ~ theory wise from the minor blues elevator to one of Coltrane's main improv motifs in "Giant Steps." So delta blues to advanced jazz, and all in between. |

musical style |

om ~ blues

|

kid's folk blues gospel

bluegrass rock country |

pop

|

adv. jazz |

||||||||

# of pitches |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

With these four pitches we bookend the 'improvisations spectrum' of our musics. And getting this close to the pentatonic five note group, we can sense its potent magic's already starting to sizzle with this grouping of four pitches. From the passionately minor blues elevator to joyous major "Giant Steps" motif, with all of four notes. Example 8. |

|

|

Recognize the four note, '1 b3 b5 b7' of the "Layla" lick in the first measures in the above idea ? Then moved from the open strings up an octave. Coltrane's idea moves his four note motif through the root pitches patterned by the minor 3rd / perfect 4th cycle. So, post bop symmetry? Yes, "Coltrane changes." While revolutionary in its application era; 1960, Coltrane's 'new' motif also goes all the way back in our Americana, pure spiritual gospel motif. In this next idea, shaping Coltrane's '1 2 3 5' motif on into a travelin' song with ... 'a banjo on my knee :) Example 8a. |

|

|

Five pitches bring a melodic kaboom. Adding one pitch to the groups of four from the last idea, we evolve our group into the now ancient pentatonic group of pitches. Endless possibilities in this group in all manner of the styles we love in Americana musics. These five pitches, so aligned together, is to our musics what denim cloth is to our 'blue jeans' Americana, casual style of comfortable clothes that look very fine and ... can work hard too, take a lickin' and keep on tickin' for dancin' on Saturday night :) Please examine the letter name pitches. Example. 9. |

|

~ pentatonic group / major and minor ~ |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

. |

2 |

. |

3 |

. |

. |

5 |

. |

6 |

. |

. |

8 |

major penta (5) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

. |

. |

b3 |

. |

4 |

. |

5 |

. |

. |

b7 |

. |

8 |

minor penta (5) |

A |

. |

. |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

There's a ton of 'theory understanding' with these pitches. Where to start? Here 'style wise' and near the beginning, we create melodies for folks songs. We also get the relative major / minor potentials from the exact same group of five pitches, retain our first diatonic triad. That there are said to be no 'bad' pitches in this group for improvisors, through all our styles, so it gives us all a super solid start yes? Thinking in the relatives 'C' major / 'A' minor with our core five pitches, sound this one a couple of times. Example 9a. |

|

Picking up some Asian wind chimes, Native American chanting vibes from this last idea? Cool. Yea no surprise then, for the five pitch pentatonic group centers both these musics and through the ages, many many other indigenous cultures around our world. Outer space too? Maybe. Never been there ... yet :) |

|

Six pitch melody crossroads. An original Americana style kaboom simply by adding one new pitch to our core of the pentatonic five; a fourth scale degree, a perfect 4th interval above our chosen root. The new style ? We'll call it gospel with its essential motion to the Four chord, in songs of both relative major / minor keys. |

Also, is there a new musical style building up from the five notes of the minor pentatonic group to a six note gospel major group ? For sure. The blues. Making the minor five pitches into the blue six we add in sharp Four, which split the perfect octave in two. In doing so find the deep indigo tritone blue within the octave's aural perfection. Please examine these relatives by letter name pitches as these groups evolve. Thinking roots 'C / A.' Example 10. |

~ gospel ~ blues ~ |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

major penta (5) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

gospel (6) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

minor penta (5) |

A |

. |

. |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

blues |

A |

. |

. |

C |

. |

D |

Eb |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

A |

Cool? One new pitch added to each of the major and minor pentatonic groups. In minor, nice to know that with the sounding of that 'one note', the blues hue magic manifests instanto. In major, and gospel, its all about the motion to Four and how we might get there. The melodic '4-3' suspension providing a supremely Americana 'amen' sigh, anytime anywhere. Example 10. |

|

Hear the '4-3' suspension in bar two ( F to E) ? Gotta love the float magic of 'sus 4.' Cool. And are the hipsters reading here now sensing the next pitch our evolutions? From groups of iv pitches to seven, where's our 'north star', our leading tone that unequivocally pulls us to rest on One ? |

Seven pitches and we're fully diatonic. At seven pitches, style wise, we're in all of the style realms. Most surely from a chords perspective. For we usually need all seven pitches to make the chords for a song, in any of our styles, even if the melody is a four or five pitch'er. Strict theory. For a song might have a pentatonic melody, but has a Four chord in supporting the line. Well, we don't diatonically get all the pitches we need in the pentatonic group to diatonically create a Four chord. Of course we use the chord anyway yes? Yes of course we do :) Strict theory says; ' must have the pitches to make the chords, borrow whatever needed whenever needed, just try to know where ya got it from. Thinking diatonically, that's what we're doing, strictly speaking. So, these seven pitches are the central group for creating all of our diatonic chords. The 7th pitch we add is the leading tone, it's also the 7th scale degree and it completes our group of pitches to create our 7 diatonic triads, a '7 7 7' :) So a major kaboom theory wise? Yes indeed. These seven pitches build the relative major ~ minor group. Now with 7 pitches in the group / loop, and by equal temper tuning the pitches, all of the vast array of diatonic harmony harmony that we enjoy today lights right up. Please examine the letter name pitches. Thinking in the key of 'C' major. Example 11. |

~ relative major / minor / modes / chords ~ |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

major penta (5) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

gospel (6) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

relative major (7) |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

relative minor |

A |

. |

B |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

|

These two relative groups, 'C major and A minor', cover a lot of ground for us, in creating melodies, triads / chords, and their colortones. |

The 'rule' we break everyday. Just turns out that in all of our musics, we tend to break this very 'number of pitches in the melody determines musical style' rather quite often. In this breakdown, our method of discovery reveals a bit of its magic. Theory rule # 1. Only the pitches of the melody are allowed to build up the harmony. Theory wise, they can be independent. Rule # 2. Any pitches to embellish the melody, or to create supporting harmony, can be borrowed whenever necessary. Rule # 3. There's only 12 pitches to choose from. Moral of the story. While all 12 pitches are available, if we borrow one or more to make our own styles of art, as theorists, we want to source them back to their own diatonic source. For example. A five pitch blues melody in a 12 bar blues in 'C', its parent scale is six notes; 'C Eb F F# G Bb C.' Our basic chords for 'a blues in C', are 'C7, F7 and G7', and we need the following pitches; ' C E G Bb ~ F A C Eb and G B D F' to build them up. So, the 'D E A and B' pitches we need for the chords are not in our parent scale, so we borrow. In sourcing where we borrow, we usually go beyond the written harmony of the song and new discoveries are often made. These new discoveries get woven into new art. Easy first source for 'C7, F7 and G7' is to think of them as a V7 or dominant chord type, then work out just what key center they are V7 in. 'C7' is V7 in 'F' major. 'F7' is V7 in 'Bb' major. 'G7' is V7 in 'C' major. In theory ~ practice. So we commonly use three V7 chords and a blues scale notes for melodies in a 12 bar blues in 'C.' None of which can be 'diatonically' created from one another or any one parent scale. A problem? Nope, not at all. But in understanding our musics, we just might want to know why, where the pitches are coming from, and explore from those points forward. We'll new the sounds we dig when we hear them, and we'll spice our 12 bar blues, all songs, accordingly. |

"Learn the rules like a pro so you can break them like an artist." |

wiki ~ Pablo Picasso |

Eight different pitches = perfect octave closure. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 C D E F G A B C Since we're breaking stuff, might as well break our own original 'different pitches melody styles' rule and add the 'octave eighth' pitch first, before continuing on to more additional colors. For in doubling our root pitch up an octave, '1 and 8', we create the outermost valence of the unbreakable 'loop of 12.' For near all dwells within the octave and has since our melody began. |

'All of our musical styles deeply rely on this perfect octave closure, a perfectly closed loop of pitches.' For in composing songs, the form used to structure a story plays a leading role, and how the pitches tell the story in musical notes is in part shaped by the form of the song. Octave closure, and the looping sense of moving towards a destination it can create, energizes how a story is told, goes hand and hand with musical form stories become songs, tales of old and new too. |

Within the octave interval. This next idea begins finding the colors within the octave's perfect loop and closure. We can get our arms around the resources as provided by the 12 pitches. Here's the major scale and a major pentatonic melody. Example 12. |

|

Cool ? Sound about right ? Cool. And finding the blues hue within the octave interval? Easy. And how about a pure chromatic by 1/2 step only riff ? Simple. Ex.12a. |

|

Cool ? Just the few pitches needed to bring the blues hue? Yep. And any of the 12 pitches of the chromatic color can be borrowed at any point to bring its magic? Absolutely. That all our colors can manifest and thrive within the octave is the core of the understanding right here. Potentially, some very essential theory in this as we gain the intellectual closure that never ever quits. |

And quitters never win, except in ... :) |

~ from 7 through the 12th unique pitches ~ |

Diatonic seven pitches / the 'other' five pitches. With 12 total pitches, and seven to create the diatonic scales, we can also think along the lines of the 'other' five pitches. As 7 + 5 = 12.

Cool ? Kinda the whole tamale right there huh ? And in regards to style and how these pitches find their spots within the diatonic, while we surely want to look at both their melody and harmony potentials, there's an easy way into the theory. For example, there's rarely ever a '#1 / b2' pitch in folk musics. Even in the blues, '#1 / b2' is more of a 'way pushed out of tune' tonic / One pitch than a true #1 coloring. Sharp One and flat Two are jazzy. Blues basis. So for a first 'easy in' to understanding these remaining five pitches / colors, we can view them as blue notes in relation to the diatonic seven, then just sort things out from there. As we ascend beyond the diatonic seven towards the complete 12 pitches of our palettes, we're thinking blue notes and blues hue, and bebop leaning jazz lines. With chords, the essential evolutions become making the four diatonic minor triads into major. Then by adding a 7th to each triad, we then easily start up the 'V7 of V' cycles, the cycles of dominant chords, we find in songs from all eras and styles. Like the blues? Yep, and beyond too, as we move by fourths / fifths around the cycle.

In chart form, next examine the letter names of the pitches, as we evolve our colors with the blue notes / other five pitches, thinking from the root pitch 'C.' And while there are surely other ways theory up these notes, these 'other five' blue notes effect do our chords, which can influence our lines. These next ideas are a sort of 'first valence' of the possibilities. Example 13. |

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

major penta (5) |

C |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

|

other five pitches |

. |

C# |

. |

D# |

. |

. |

F# |

. |

G# |

. |

Bb |

. |

. |

arpeggio degree #'s |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

evolve tonic I to become V7 of IV for a stronger, more authentic cadence motion to Four |

C |

E |

G |

Bb |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

||||

relative minor triad on vi evolves to major, becomes V7 of ii |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

. |

||||||||

ii -7 evolves to a major triad / now V7 becomes V7 of V |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

. |

||||||||

iii -7 to major / V7 becomes V7 of vi |

E |

G# |

B |

D |

. |

||||||||

vii -7b5 borrow two pitches / to major / V7 becomes V7 of iii |

B |

D# |

F# |

A |

. |

||||||||

Letter names or numbers? In designating the root pitches of triads and chords, both letter names or their numbers within a key center work fine. Whatever is best for you to be correct is best. If your style of music stays near the 'diatonic 3 and 3', chances are letter names for chords are just the ticket. Also, when working with other artists, sensitivity to their ways of how they label chords wins the day to getting the right chords at the right times. All that matters really is getting on the same page and making your musics together, whatever anything in the music is labeled etc., that works, works :) |

For some jazz leaning readers here, further on down this 'letter / number' theory road, there's an idea we term 'chord type.' Thinking along these lines moves us beyond one key center's 'diatonic 3 and 3', and we can begin to borrow chords form other keys based on 'type,' Here the numbers begin to take the lead. It's just easier usually as we lean towards a jazz styling, where there's often lots of chords with assorted color tones to keep track of. And once moving in this way of thinking, we'll usually apply the numbers to all our elements, as we take on a more fully 12 tone vision of the resources etc. In doing so we categorise chords by their function. By what role they play in music. Do they create a sense of tension, of release, as a passing chord, minor or major colors within a chosen key center. Chord type simplifies a lot of our vast array of harmony. |

As roots of chords. A next evolution with these five non-diatonic notes, yet still thinking within a diatonic scheme of a key center, is to make them the root pitches of new chords. These root notes, we chromatically slip in between the diatonic positions, and evolve a song's bass line story. More chromatic = jazz it up ? Exactly. Please examine the pitches, the 'other five' we're adding now in billiard balls and da bold :) Example 13. |

5 pure blue notes |

. |

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

||||

scale degree #'s |

1 |

b2 |

2 |

b3 |

3 |

4 |

#4 |

5 |

#5 |

6 |

b7 |

7 |

8 |

7 relatives major / minor / oct. close @ 8 |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

C |

blue note / 5 remaining pitches |

. |

C# |

. |

Eb / D# |

. |

. |

F# |

. |

G# |

. |

Bb / A# |

. |

C |

12 pitches / chromatic enhancement |

C |

C# |

D |

D# |

E |

F |

F# |

G |

G# |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

|

'C#, D#, F#', G#, Bb.' Mixing sharps and flats? Oh well, common practice dictates yes? Thinking 'flat 7' is way more common than '#6.' So, these passing chords are a way to 'jazz things up a bit.' The passing diminished color becoming not only an accelerator pedal to zoom up our sense of forward motion in our chord progressions, but as part of V7b9, our portal to our chord substitution universe of all things leaning towards the jazz stylings and finding news ways for the same old same old. |

So ... which goes where? So which of these five pitches that we add to the mix is really a matter of taste, choice and of course, necessity. What style are we creating in etc., helps determine which of the five. Thinking here along style lines, and with 'C' as our root pitch to measure from, a few generalizations about these color tones and a common placement of their aural magics. Add 'Bb' / 'A#', the b7 / # 6 for folk: Very common to add b7 for tonic Mixolydian color and build a real V7 chord for motion to Four. In 'C', adding in 'Bb / A#.' Add 'F#' / 'Gb', the # 4 / b5 for blues and jazz: Blue melodies love all the blue notes of course so thinking chords now to find something new, the #4 / #IV / tritone note and chord is a way to jazz lean things with just the one pitch / chord. The #4 also gives us our first 'V of V' cycle, 'D7 to G7', so essential in our Americana songs through our spectrum of styles. In 'C', chromatically adding in 'F# / 'Gb.' Adding 'C#' / 'Db', the # 1 / b2 for pop towards jazz: Pop chord progressions love to cycle by fourths and fifths, often across the wheel to somewhere and then pedal on back to home. The #1, a wailing wailing blue note, also gives us our key pitch to create another click back on our 'V of V' cycles and of course the great accelerator itself, the '#1 diminished 7th chord.' In 'C', adding in 'C#.' Flat Two as a root pitch is a bossa nova / Latin style staple, and in theory, based on the tritone substitute chord from V7. Flat Two, 'b2', up an octave is the 'b9' colortone, a common jazz passing tone and the 7th of the fully diminished 7th that lives atop V7 :)The b3 / # (sharp) 2 for pop toward jazz: Total total blue note honker. As a chord usually, #2 ='s an ascending passing diminished 7th chord between the diatonic Two and Three chords in the up tempo, soloing through the changes jazz realm. It's also an old timey chord descending to Two, so in both cases creating a hint of that common tone diminished color from the blues. In 'C', adding in 'Eb / D#' to the line. The #5 (sharp) for pop toward jazz: With #5, three main new chords / colors found in pop and beyond are now diatonically available. We can augment our tonic triad, creating a rather unique motion to Four. While mostly pop and jazz, this comes along in the country styles too. And with #5 we also evolve a V7 chord on the diatonic, minor Three position, setting a stronger, even 'old timey' passing chord motion to both Four again, or to our relative minor on Six. Both of these motions are not uncommon in pop chord progressions. In 'C', letter wise simply adding in the pitches 'G#' / 'Ab' into the mix :) |

Songs by genre and musical style. These next ideas examine our most common styles and genres of songs with our various numerical musical creating devices. All in good fun really and mostly a review, and of course all in theory. For anything can be anywhere is the art of making art. That we each can find our own best way to understand our own music, yet all share of and from the same 'well of knowledge', is the Americana way. That all our musics in the Amer Afro Euro Latin weave today share a global music theory and vocabulary connects us all together through the powers of moving pitches through time :) |

Children's songs. Our most theory basic songs are ones written for kids and usually rhymes of special words that we love. The theme for the words power the melody. Kids Americana songs usually have just a few pitches, often arranged as a major triad with a jaunty air. Mostly stepwise in construction as it is easier to sing, there's often a sequence in the line to generate some motion to the closure of the story. Repetition often wins the day. Time and tempo. All about telling the story of the songs, finding a tempo for the words and their rhymes. Mostly in the 'big four' or in 3, all of the Americana lines have the DNA to swing easily with great joy. Melodies. Clear, sequential, stepwise and triads are all common. Strong beginning and clear ending bringing the melody line to rest. Arpeggios. Most often on the tonic pitch and One chord, many of our melodies made with triads. Chords. Principally One and Five, and really any and all in competent hands. Remember simple can often be a solution and sometimes the best one too :) Form. Two, four and eight bar phrases repeated over and over. Also, 'mini' song forms are not uncommon. Color tones. We find the major 6th in more adventurous lines of major pentatonic, the minor 7th of the pentatonic minor in many minor melodies. Improv. Mostly in the vocals and storytelling, instrumentally maybe 8 bars per tune per player in performance ... ? Jazz players might consider keeping their solos shorter ... until asked for more :) A song to learn. Rote learn by ear your favorite song that you learned as a kid. Too easy? Run it through a couple of keys. Still too easy? All 12 keys. Create a chord melody of it? Find a 2nd favorite and run it through the same same process? Essentials suggestion, "This Old Man." |

"Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication." |

wiki ~ Leonardo da Vinci |

"Really? Could be, because then everyone who experiences 'simplicity in creative art', gets a thought of their very own from it, based on their own experience, from their own ways of doing the walk of life." |

Maybelle Carter ~ folk / country songs. In performance, our Americana folk songs are almost always sung, for in folk music, there's a tale to tell, a story to be told, usually about, well folks :) While instrumental versions are not uncommon, and soloists will 'theme and variate' the written melody of a song, vocal tunes are surely folk style favored. We know that the voice paired with a stringed instrument goes way way back in our evolutions. Also, thoughtful and heartfelt harmonies in the voices will win the day every time. For we've had this music all along. Folk songs tell a story that most folks listening can understand and identify with in spirit. Guitarist Maybelle Carter was there at the beginning :) Click pic for audio. Often retelling our histories, our Americana folk styles and songs captures in music our historical events for the ages to remember in song. Mostly pentatonic in melody, three chords and the truth from the diatonic key center often rules the day; One, Four and Five as triads, with a 7th on Five, so V7. Time and tempo ~ 4 / 4. A 'walking tempo' is most common in 4, in 3/4 time are the waltz's and 6/8 begins to appear to help the swing along. Folk dancers tend to do steps together, clogging and square dancing are still fairly common, line dancing too leaning country. Melodies. Diatonic five to seven pitches to capture the emotional quality of the words used to tell the story of the song. Simple, heartfelt, humourous and sincere, to tell any tale of the sameness of humanness we all share and live each day in commonality. Arpeggios. As in children's songs, the three note major and minor triads still rule the day as folk motifs. Chords. Principally One, Four and Five triads. Here we first solidly enter into the realm of the 'diatonic three and three.' One / Four / Five progressions in both major and minor with the one key center, relative major / natural minor pitches. These six chords create the basis of the harmony weave of a gillion or so Americana folk styled tunes. Remember that simple can be best too. Form. Eight bar phrases double to 16, which then doubles to 32, the most common of our song lengths historically, excepting the 12 bar blues of course. In the longer 32 bar forms, often there are two themes, one major one minor, providing a balance for the 'two sides to the story', a creative retelling the ups and downs of a tale we can all have a piece of in common. Color tones. Again Six is most common, although any open tuning can advance the coloring up of the triads right quickly. Surely a hint of the Americana blue hue, all throughout the literature, all throughout our history, some genres more than others. Improv. Mostly in the vocals. Some cats yodel along which is a hoot, crowds love this. It's so rare nowadays that it'll bring the house down pert near every time :) I've seen this magic many many times. If new to you, try some improv yodeling along with your song and see if you don't initially bust up laughing. Work it into your act and behold its joyful magic on audiences of all ages. Solo breaks are not uncommon but now we're leaning stylewise towards the bluegrass side of the dale. If ya get the nod to play a few bars, maybe just find some of the melody. Having something cool for the last hold can be a nice added sparkle and touch in closing. A folk song to learn. Into the wayback for Essential's suggestion of "Oh Susanna." An Americana love song fave, just a perfect pentatonic jaunty a la ditty, which can swing super hard, is old timey, yet a great dance tune too. Recorded by so many folks stars over the decades, it's just a shame not to know today, and even share once in a while in these modern times of the sophistication of near everything. Like making an old fashioned public school music book into this fancy 'e' book? Prolly :) Ye haw and a woo hoo too ! Another first bluegrass song to learn. Hands down choice here ... "Roll In My Sweet Baby's Arms." Man this tune can cook ! Gets the dancers right up and even singing along when gently encouraged. Find a recording and learn it by ear. |

|

Blues songs. The blues is a wide wide strand in the fabric of our Americana musics. For we can find its blue hue in just about every style, genre and sub genre imaginable. Well maybe not kid's songs. In theory, initially based on combining pitches from two our main ways tunings; natural and equal temper, we rub these notes together to create its hair raising blue magic. Intro's. There's really just two that need to be initially mastered that will end up working in lots of essential spots through all our Americana styles. There's the "Muddy" and the "Elmore" intro licks, each here named after the artist that they are often associated with. Time and tempo / a 2 and 4 backbeat / dance. Folks love to dance and listen to the blues. For it is easy to follow right along with the band and story being told. Dancers can improvise / choreograph their steps right along with the improv of the music. Blues is almost always in 4, tempos vary between slow to the brighter shuffle, where the triplet feel of 3 is layered over the 4, making for the 6/8 or 12/8 'shuffle' feel. That both of these time / rhythms are in the basis of swing, ties the blues with the jazz styles. Melodies. Blues melodies backing the vocal lines are usually just a couple of pitches. Longer sustained blue note vocals are common. Based on the blues scale; the minor pentatonic group with an added tritone, the words and pitches, shaped into 4 bars, are often simply repeated 3 times to create the form of the song. 4 x 3 = 12 bars And while there's variations of course, most of the lasting literature is in the 12 bar form. So, three, four bar phrases. Two repeated phrase as the 'call', and the last phrase as the response is most common and tells near any story in a natural way. This writing format has now worked like a charm for about hundred years, more or less. Got any blues hooks needing to be developed into a full song? Make it a blues ? Arpeggios. In the blues, as in folk as in rock and country and anything with a gospel hue, the three note triads really rule the day when arpeggios are in the melody. In either an ascending or descending direction, triads rule the day. Blues bass lines are for the most part created from consistently arpeggiating the chords. In the bass lines, arpeggios often include the 7th to sound out the pitches of the backing V7 chord basis of blues harmony. Chords. Principally the One, Four and Five chords, with a big push to Four is very very common, and in the chords and harmony is where the pure diatonic theory goes quite wonky right quick. Crazy theory rules. Thinking of a 12 bar blues in 'C', each of the three principle chords are V7 styled, dominant chord type. While they share pitches in common, there's no easy diatonic basis to theory build it all up. Its tricky. The melody notes can be either in the chords or not. If the band decides, the 12 bar form is not negotiable in performances, everyone sticks to it, and even when mistakes occur, there's always the top of the form to agree upon to begin anew and correctly together, of if not, as the case may be. Functional harmony. In the blues, our parent scale for the melody pitches does not have the pitches to create the chords, so there's no diatonic relationship. So all of our studies of 'scales ~ arpeggios ~ chords, associated with all the diatonic 'rules' of the Euro library of musics, and all the chords in our Americana styles, folk through jazz, everything except the way a basic 12 bar blues and its chords and progression. Crazy, as the 12 bar blues sits right at the core of it all, and its 'in theory' is like no other, ever. Before or since I'd imagine :) So we've already broken our first rule of diatonic harmony. A concern? Nope, just want to know the combinations and sources for the pitches. Quick review chords. That the One, Four and Five chords in a major key blues song are all V7 chord type, so they all contain a tritone between their 3rd and 7th. Concern? Nope. So in sorting it all out there's a lot of borrowing pitches. Problem here? Nope, but very often create quite a tangle to decipher from our Euro diatonic perspective, our essential basis for understanding most musics. So, does any of this theory mumbo jumbo matter when writing or performing blues songs? When we get 'under the lights' as they say? Good question amigo. When writing and shedding, I'd say yes theory matters big time, but then I'm a theorist. Knowing the theory provides imaginative options for our creative. And when performing? I'd say no, the theory of it is built in to what we're playing, the form, chords etc. Because once under the lights, the magic begins anew each time we count it off ... :) Must be something in the light, never fails. Poof ... 'what was I thinking ?' Concentrate and play perfect :) Blues in a minor key. In a minor key blues song, same 12 bar form generally, the three principle chords are minor 7th, what we can term a Two chord type; a minor triad + minor 7th. Thus, way more diatonic in overall construction. The major to minor ratio of key centers of 100 blues songs that get played regularly is about ... maybe 10 songs in major for every one minor. Yet, in major key blues, there's a ton of minor pitches in the melody line. Actually, the best of the blue notes are the minor intervals, in relation to the pitches used to build up the chords that support them. This all revolves around the major 3rd of the triad in V7. Blues rub ? Blues hue ? Create blue magic ? Exactly. Rub the blue 3rd against the major 3rd of a V7 chord. Form. The four bar phrase and motion to Four are the 'Four Kings of the Blues.' Most blues songs string three of these phrases together making 12 bars. This is the core Americana blues form. And while there's all sorts of variations in length of form, this 12 bar blues form has been our continental standard for eight or nine decades now, and is surely also heading towards global recognition, becoming known as a musical form that quickly brings like minded cats together right now. Stops in the form. When the band cuts off and the beats keep on clickin' right on by, is a blues tradition. Super potent in framing a 'moment', it opens up spaces for making super memorable moments, often off the cuff too. The cut off on beat one, bar 10, is probably the most common through the literature, as it clears the way for setting up the turnaround lick, aiming it all to beat one of bar one at the top of the 12 bar form and onto the next chorus of the 12 bar form. one chorus = 12 bars :) Like in jamming? Yep, but ... using the 12 bar blues framework for establishing NEOGROUPTHINK that gets everyone on the same page, and globally now too as the 12 bar form is world renowned. And with a measurable framework to organize pitches, chords and music time all together, builds an interactive group magic that is recognized and shared by the players, the listeners and dancers alike. And when everyone in the mix can follow along together, there's a new type of potential for creating community through our music. Color tones. As the blues is mainly a V7 based genre, the most common color tones are the ones built off V7. That melody pitches, the blue notes, are often not part of the basic chords, advanced players will often find these tones in the chords in their supporting role behind the singer. The #9 of V7#9 is the blue 3rd and fairly common. The diatonic 'nine' color of the V9 chord makes the core harmony for all sorts of funk styles. Eleven is common in songs in a minor key. Thirteen is the color tone for all sorts of blues grooves; jump, swing, rockabilly etc., whether the 12 bar blues form is the overall structure of the song or not, as the case may be; the 6 / 13 colortone in chords swings. Blues chord hue mixed into other styles? Exactly. Americana core? Yep. Improv. In small group performance, I've ever yet to see cats reading their music on the gig. So in that sense, the whole tamale is being created live, thus improvised; everyone making up their parts together ... from memory by practice ... as the music moves along, they hear it as they go along and knit their part into the mix. In addition, there's a lot of soloing as each player can get an opportunity to 'testify' about the story being told. While usually a two chorus minimum, stronger players need more space to work up their magic. In regular jazz performances of the 12 bar blues, in medium to brighter tempos, taking a half a dozen choruses to 'build' a solo is not at all uncommon. Dynamics. The loud and soft dynamics of the music is probably most apparent in a blues performance than in any of our other musical styles. Getting the whole band underneath evenly in volume, so as to hear the whisper of the soloist to their shouting release, is the range of dynamics that can happen in every song. Very very difficult for a band to do consistently well. That said, the repeating cycle of the 12 bar form gives ample opportunity and an easy target for everyone to bring the volume down at the 'top' of the form. We just have to remember to do it or gently remind one another along the way. The profound effect that volume dynamics have on the art being created, and the audience as well, is a magic to know. And well worth the effort to strengthen the dynamic ability of an improvisatory collective of players; for a little bit of discipline can take us a long long way. A song to learn. The author's own "The Truth Is." |

|

Gospel songs. Add folk and blues together and we get gospel. Just as with the blues, our gospel music qualities are a wide wide band in the fabric of our Americana musics. As it evolved early on in our American history, say around 1800 or so, it has been with us all along. Evolving form the purely vocal spiritual songs, in today's homophonic musics, and especially in women's vocal lines, there's just a ton of this 'gospel' crossover with the blues. Time and tempo. Gospel music is designed to include all souls in the room through storytelling. A stately 'walking' tempo of 60 is a starting point. Themes are universal, about love and spirit, doing good deeds and remembering there's a reckoning for each of us individually that's coming, on down the road. How we disport in our community, becomes individual at the close. Heartbeat paced tempos give listeners a chance to reflect on the idea and respond in kind. The 'call and response' format between voices, found in all of our Americana styles, is rooted in gospel music. The 4/4 pulse the common beat throughout the songs. Melodies. Melodies are diatonic mostly, with occasional large dollops of the blues hue adding to the testimony of the partakers. There's a six pitch styled major scale sans (without) a leading tone pitch, that gives us the carefree of the pentatonic five, while including Four. Motion to, and from, Four is the core DNA of gospel. We use it in all of our styles to 'bring some gospel' into whatever style we're creating in. Chords. Principally mixing the diatonic major and minor One, Four and Five chords, i.e., the three and three. The blues influence often adds the b7 to the triads, though diatonic is the harmonic basis. Motion to Four is the core of it all. There's no other chords in gospel that hold such prominence; One to Four. In gospel songs in both major or minor keys, motion to the Four chord and back to One is at the core of it all. Form. The musical form for gospel is most often written around the call and response of the lyrics and story. So things tend to be measured up equal, with four bars getting it done. Counted like this; 1 2 3 4 / 2 2 3 4 / 3 2 3 4 / 4 2 3 4 / 1 2 3 4 ... Double four into eight bar phrases, quickly becomes 16 bar and into the longer 32 bar forms, the AABA and AB, are also common, though suited more for listening perhaps than the tighter phrasing of the back and forth of call and response. Color tones. The added colors to the harmony often revolve around adding the '6th' to tonic function chords. Otherwise triads rule the day, giving the melody a chance to proceed unhindered by the colors of the chords. The stories and message in gospel music is one of simplicity, and the harmony and color tones support and reflect that. That said, the vocal melismas of seasoned singers is probably beyond being accurately notated, as melodically complex, and oh so Americana, of any vocal lines we might ever hear. As cool as it gets? For some yea, and hair raising? Yep, that's the idea. Improv. There's some blowing in gospel, though often limited to just sections within a piece. As the organ often plays such a role, its sustained pitch ability creates some wonderful crescendos. Often the leader of the music will improvise a dialogue with the listeners, so everyone gets a chance to testify and add in their own spontaneous magics. Dynamics. Since gospel music is so cool in telling stories, players need to be good listeners and super keen on following the nuances of the singer / leader of the session. Experienced leaders of gospel bands develop their own ways to tell the band what to do while performing. A lot of this is looks and hand motions. And while the musical parts are generally within the grasp of most players who try, following the soft / loud dynamics generated by how the story is being told, is a supreme challenge at times. At the close of many performances of gospel music, there's often a coda that just grooves along, most often between One and Four, creates a vamp, that gives everyone a chance to join in. These codas will often get louder and louder till there ain't no more to get, at which point, the leader conducts the band out, often with a series of holds, giving everyone a chance to catch on to the end nice and solid and thus finish and come together. A gospel song to learn. "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot." |

“Fats, how did this rock ’n’ roll all get started anyway?”An interviewer for a Hearst newsreel asked him in 1957. Mr. Domino answered: “Well, what they call rock’n’ roll now is rhythm and blues. I’ve been playing it for 15 years in New Orleans.” wiki ~ Fats Domino By Jon Pareles and William Grimes Oct. 25, 2017 |

Rock songs. Coming right on out of the blues of the 1950's, early rockers followed close to the 12 bar blues form. The earliest 'official' rock songs followed the boogie woogie arpeggiated V7 bass line for each of the three chords right on through the 12 bar blues form. Perfectly. Since then there's been no limit to the creative direction rock music has taken in expanding from this historical basis. Telling stories is still the core. The juice of young love, that at some point bursts from every heart from each new successive generation, is often the magic elixir to energize the next top 10 hit. Evo ~ gear. The evolution of the gear for guitar players, through the succeeding decades, plays huge in the evolutions of the various styles and genres of all of the rock music we inherit today. While mostly looking for longer sustain on held notes, the various signal overdrives rockers love often call for readjusting the combinations of pitches we choose to sound together. So chords? Yep, the chords. The 'power' chords? Yep, the power chords. For example. Example 14. |

|

|

Cool? Simply that less pitches makes for less confusion as the pitch orbits of each string of each note in any chord goes through the amplification process. So where's the big roar in the last idea, sounds vanilla ? Well, that's your business to jazz it up :) |

|

What makes 'rock rock.' Time and tempo / rock style music hits on beat one. Folks love to dance to rock music so its tempos are danceable, to slower for slow dancing :) The big 4 beat again is king. And while the 2 and 4 backbeat fills the dance floor, rock likes to hit on the downbeat, 1, first beat of the measure. In essence, rock music is rock because it hits on one ... So drums, bass, guitar, vocals etc., phrase to beat one, nearly always followed by the snare hit on 2. Melodies. While there's a lot of rock instrumentals, most rock melodies are sung. Melodies are usually blues based or if more major scale, then leaning towards a more pop direction. Critics often distinguish between a 'singer' and a vocalist.' A singer finding more art in the presentation of the pitches of the song's melody and a vocalist more focused on fronting the band and putting on a show, telling their stories with oftentimes with more bravado and showmanship than pitch expertise. Chords. Principally mixing the diatonic major and minor One, Four and Five chords, i.e., the three and three. The blues influence often adds the b7. Thanks to the evolution of the gear, today's rockers are often just working the root and fifth of the chords, modern power chords I guess. Early 50's rock and rockabilly used more triad based ideas, with the major 6th chord adding in the jump feel of rockabilly and its swing. 60's power chords were barre chords with a fair amount of doubling in the two core voicings. 70's begin the digital gear evolutions and its balance of a return to analog hand wired rigs. So from the 5th's of metal to the beginnings of the V7 blues and V9 of funk and into jazz harmonies, all of our chords can find a home somewhere in the rock stylings. Form. The 12 bar blues is not uncommon especially early on and also in rock adaptations of true 12 bar blues tunes. The four bar phrase still reigns supreme, getting linked like boxcars to tell the tales. Intros play a big part in rock. Signature riffs to kick off a tune are still among the most sort after pitches in the biz. Color tones. With its blues basis, rock colortones mostly lean the way of the blues. But anytime there's some pop in the rock, all of the diatonic colortones are in play. Any sort of theatrical rock will surely stretch all of the boundaries of all of our elements. Improv. Rockers, like blues players, generally are not reading the music they are performing, thus they are improvising their parts often based the rote learning of their part in the music. Through repetition their parts become second nature for performance. The rock soloist often holds the top spot among the fans, when both lead singer and soloist are the same cat, the potential for superstar status begins to align. Dynamics. Since "Stairway To Heaven" was released, rock composers love to mix and balance quiet sections with a full on musical blast. Time and again we hear top 10 songs with acoustically sounding intros or verse sections within a song followed by the full roar of the chorus. Not too sure if the opposite is true. A blast of a verse with acoustic chorus. Regardless, rock is music that is generally played loud. Over the decades of its performance it'll take a toll on one's physical hearing abilities. Be mindful of your ears around loud and powerful sound equipment. Although some might quip ... 'if its too loud you're too old ...' if we can't hear it then we can't hear it ... at any age. Be careful, we only get two ears, and all the stuff inside that make them work, which is a lot of very small parts, and they are way hard to fix. 'A word to the wise is sufficient.' |

|