~ Aeolian mode ~ submediant ~ ~ diatonic relative minor of major ~

'... half the whole tamale and for some ... way way more ...' 'the natural minor balance of major ...' |

Ol' number Six in a nutshell. Ol' Six is the home of so much mucho coolness in our Americana theory that it's hard to know where to begin. For on the major 6th interval / pitch above our root pitch of the major scale, we find the tonic center / One / root pitch of its relative minor group. If there's a core DNA, 'Yin / Yang' two parts to our system of theory, One and Six are its modern basis that has also been codefied in the books for the last 500 years or so. In getting started here, there's a couple of cliche ideas that are 'pure major 6th', original pure Americana, that kicks off this discussion for us by ear. |

Flip side nutshell. Up top in the title of this page is the quip 'half the whole tamale' and for some artists maybe more. Meaning that if your musical art is centered on the minor keys, its songs and stories, its melodies and backing chords, then what we are calling here as 'Six' is actually your tonal key center, tonic pitch and One. Many reggae artists hang home in these colors. Latin and blues rock guitar legendary Carlos Santana might refer to these minor tones as his centering pitches, conveying their timeless qualities of passion and empathy in truly sentient ways. So for some folks, all things Six are really all things One. Then all things One become all things Three. You choose ... cool ? |

|

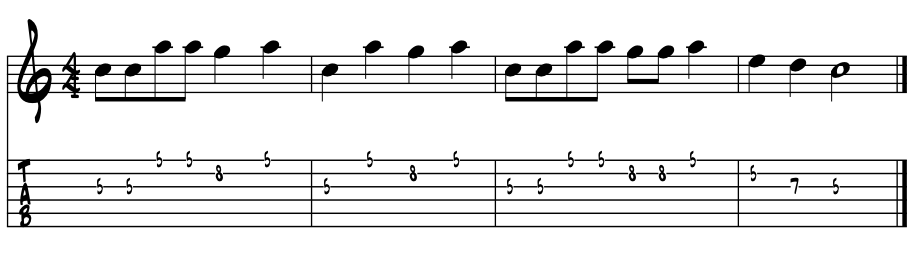

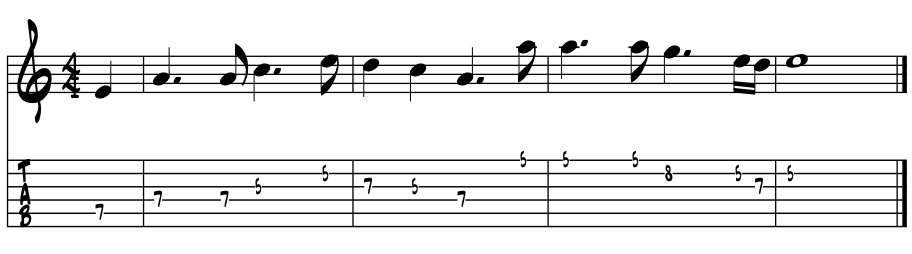

Cliche country lick features Six / major. This first idea finds the major 6th interval as a key note to create the jaunty major pentatonic color, at the heart of many classic Americana melodies. Hollywood 'Western' movie music scores often include this lick's character. Classic and old timey, yet good to know the theory basis of. Here we build the same interval lick, '1 5 6 5' off of the One / Four and Five chords. One idea diatonically filtered through the changes. Ex. 1. |

|

Remember this quotable lick? From the cowboy songs such as "Happy Trails" of the 1950's. These pitches and basic riff make a great bass line for blues and gospel. Add a 'b7' atop for some R and B / rock and roll spice. |

|

A first evolution. On down the trail a ways with pretty much the same pitches, we take an elegant one finger barre chord, add in a new beat and a core of it all rock and roll riff evolves. Ask your bass player to thump on a low 'C.' Example 1a. |

|

Got this lick under your fingers? Do learn it here if need be. Fairly easy and loads of fun, there's a ton of tunes that love this sort of motor. |

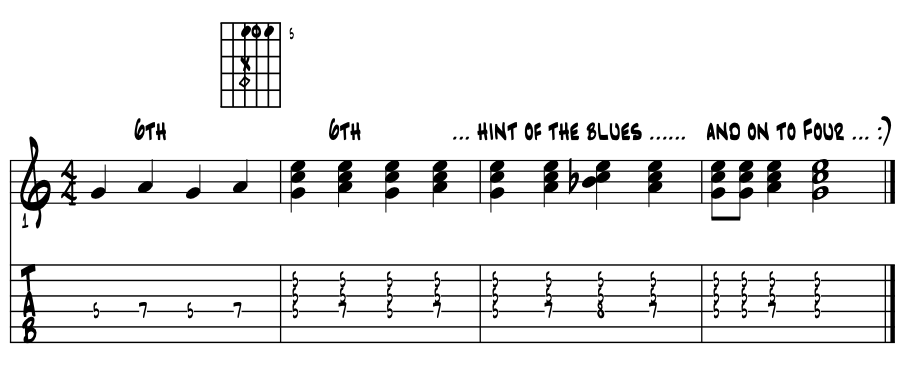

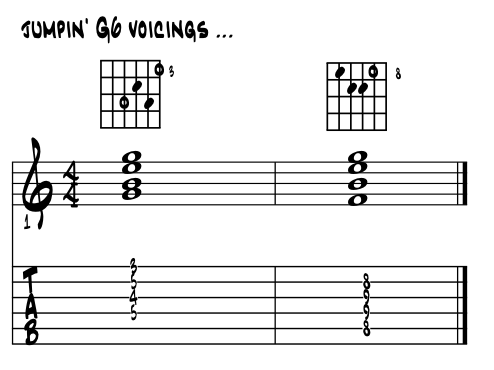

Wanna jump ...? As in ... ? A 'jump blues?' Rockabilly style? Here's two chord voicings that will work the magic. The first is 'G' 6, bright and tonic tight. The second has a b7 in the bass, so 3rd inversion with a bit more rockabilly V7. Example 1b. |

|

|

Know these shapes? Major triads with 6 / 13 colortones. |

Theory overview. In theory, we can measure Six from the root of any major scale and get the major 6th interval, finding a loop of pitches that creates the natural minor grouping of pitches. Relative of Ionian major, Six becomes the tonic pitch of our minor tonality; pitches, arpeggios and chords. The Aeolian mode is built upon Six, which brings along its history of melodies. |

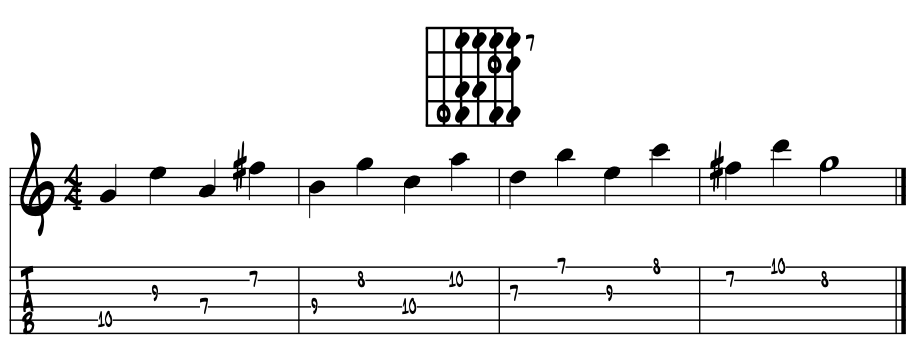

A core America musical color. The major 6th interval becomes a key color of our early Americana melodies. Dig the jauntiness following line. Have this one under your fingers? Maybe from the fourth grade played on that kazoo like wind instrument. Example 2. |

|

"Shortnin'." Starting with an interval leap of a major sixth, the above melody just might be the classic capture of the major pentatonic scale's five pitches creating the optimism often associated with the American dream. |

Able to get this line to swing? In one sense the swing is built right in. And if we can capture the swing with the easy ones, then just a matter of practice to add swing wherever comes along. |

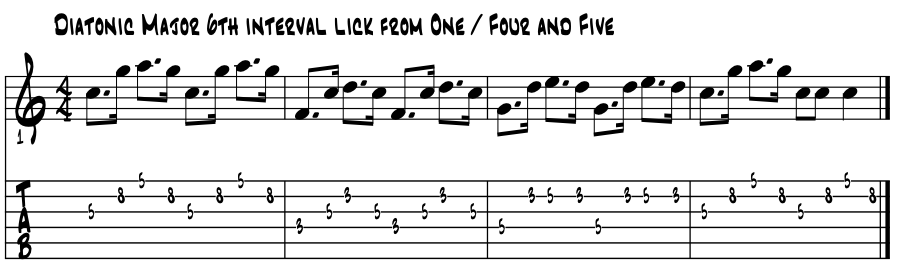

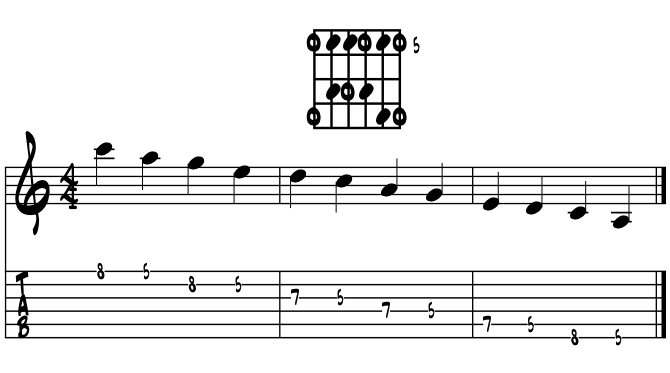

As a sequence. The interval of a 6th makes for a nice melodic sequence. In this next idea we simply sound the pitches of the G major scale in ascending diatonic sixth's. The scale shape above the staff contains all of the pitches of the lick. One of five core shapes, this one centers a lot of melodies for guitar. Example 3. |

Not an easy task is it? These interval type studies are the calisthenics for pro leaning players. Grist for the mill as Dr. Miller would say. In improvisation, just the leap itself gives an artist room to move. And isn't that the 'gospel butter' shape from the jazz guitar method ? Yep, sure is. |

Six as a colortone. We can add the interval of a 6th to a major triad and create a very cool and fairly essential chordal color. For it's often associated with the early days when country music was first beginning and later mixed with rock'n roll into what becomes 'rockabilly.' In any of our musical styles or genres, that include the adjective 'jump' in their description, chances are the 'tonic One 6' chord is in the neighborhood. |

|

In this next idea, we create a pentatonic sequence and close out the line with a tonic One 6 chord. Maybe put a bit of your Tele twang on this one. Example 4. |

|

From this last idea we might get the sense that these tonic 6 chords are good choices for the last hold of an arrangement. Nowadays they are probably a bit towards cliche, but who cares ... as they surely work the magic in ending songs on a bright and joyous chord. But wait ... there's more ... :) |

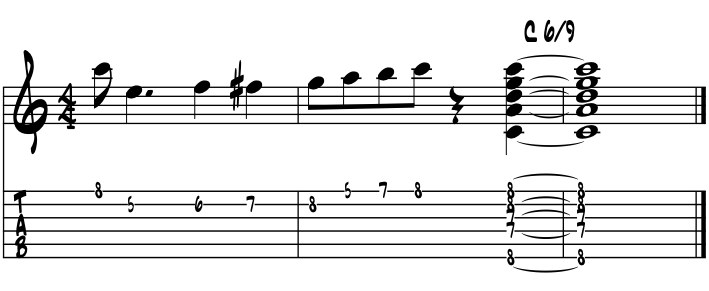

Tonic 6 / 9 chords. We might as well jump ahead a bit in the theory and include a tonic One 6/9 chord right here and now. For with one added pitch stacked just the right way, the theory goes 'kaboom' for those so inclined. For '9' is a seriouso colortone in so many ways in both major and minor keys. For there's minor 6 / 9 too of course. |

Simply a one pitch enhancement to our tonic 6th chord, we keep the major 6th and pair it with a pitch that's a major 9th above the root of our chord to make 6/9. In doing this we end up stacking fourths, thus a venture from tertian to include some 'quartile' build too, creating just a very happening and joyous chord for all who know of it, and discover some cool spots to work its magic. |

Just a suggestion here but if ever you need a closing chord for an arrangement, that's tight, bright and light, for any of the country / bluegrass / rockabilly towards a jazz direction, try this 6/9 chunk. If still necessary, learn this essential cliche riff, perfect way to close out a song, here capped with voicing of 6/9 colortone coolness. Example 4a. |

Find the chord shape ? Tight and bright yes? This last idea is surely '12 key' worthy. With endless endless variations among players, master it and add your own 'takes' to the Americana library of cliche endings. And note the easy fingering? Explore on your own to find this lick on other string sets. Go ahead and get lost. Then find your way back. Even take the wayback if necessary. Add this lick to your shedding list for warming up till its all worn out. And then when ya need it, you'll never miss it again. Well :) Time to take a ride on the "A Train ?" |

|

The 'flip side' of Six / relative minor. Using the same grouping of pitches, we create another American classic melody. This comes from the flip side of the major pentatonic group as we build its relative minor from this same sixth scale degree. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 C D E F G A B C 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A B C D E F G A |

Using the exact same pitches in creating these melodies, a new center pitch is chosen from within the group and we then respace our pitches accordingly. The intervals between each of the pitches? Yep. Intervals between the pitches determine all its colors. Know this old time melody yet? Learn it now if need be. Example 5. |

Cool? Cool. This one goes way back, even back across the pond, though written records are scarce. Metalist of NYC Queens Leslie West had a nice cover of this song. |

|

"The Rising Sun." The just above classic early American melody is created exclusively from the pitches of the minor pentatonic grouping of pitches. For we guitar players of the popular American styles that include any of the blues / rock colors, these two groups; major and minor pentatonic, are by far and away the mainstays for creating our melodic lines. That the same pitches can create both the major and minor pentatonic colors, maybe no real surprise that they come from the same scale shapes also. |

A first shape. Both of the above melodies can come from the same scale shape. Learning these shapes can get the pitches quickly under our fingers for playing lines, both established melodies and our improvised ones. The following shape is a common first. |

For it fits nicely under the fingers, works with the open strings, moves up and down the fingerboard 'in soto' oh so sweetly, loves to accommodate additional pitches in between the dots, and depending on your strings, holds lots of cool and essential string bends for finding the blue hue. Slow down a bit and learn it here and now if need be. Shed it up and down the neck a few times and it'll be yours forever. Example 6. |

|

Shedding this shape. In shedding this shape perhaps keep in mind a couple of things. The circles are the root pitches of the C major and the A minor pentatonic groups mixed in together. Move this shape intact up and down the fingerboard for the other key centers, easily finding the tonic pitches on the 1st and 6th strings. |

And while it falls neatly into the four finger / four fret fingering solution, not at all uncommon for blues players to rely on using three fingers. The pinky idle. This might be due to the strength needed for bending. A lot of cats put middle / ring together to get the strength to bend the metal string to the right pitch. Beyond tricky, just stick with it if this is your thing. Yet, whatever consistently gets you the sounds you dig is probably going to be the best fingerings for you in the long run. |

~ stgc / do rote learn this bit of theory ~ |

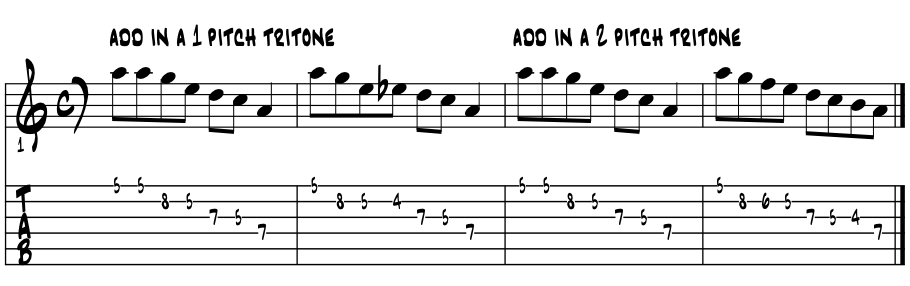

Evolving the pentatonic into full Americana. We can readily evolve the pentatonic pitches and its scale shapes by adding in pitches to include the tritone color. In doing so we move into the diatonic realm and all of its magics throughout its vast domains. |

We evolve this two ways, each addition a bit different for major and minor. A one pitch tritone into minor to make the blues scale. A two pitch tritone interval into the major to make diatonic Six, combine to create the relative major / minor group of pitches. Example 7. |

|

|

Cool with this? How's that for a theory kaboom ? This last idea is the basic evolutionary theory of a rather large part of what we Americano guitar-amigos do. Simply mixing ideas from each of the two groups together, melodies with blue notes from the minor group with a one pitch tritone. And full on chords created from the seven pitch, two pitch tritone relative major / minor scale. We motor this double helix weave, motored along on 2 and 4 backbeat, for pure Americana musics. |

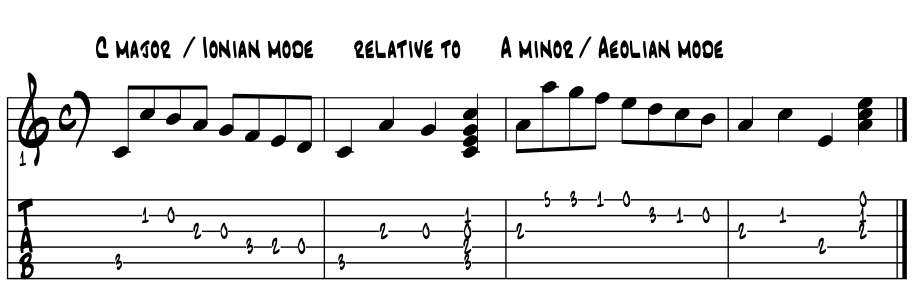

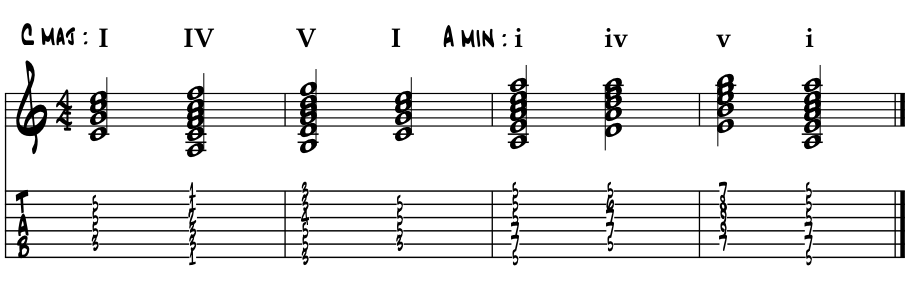

Aeolian mode / seven pitches makes for a functioning key center. Again using of the interval of a major 6th, we locate the root pitch of our seven pitch relative minor scale. That this major / minor pairing lives at the core of our music theory and these two positions, tonic's One and Six, are the twin anchors of this dual magic all from the same pitches, is a keystone of our formal theory studies. Please examine the pitches in C major. Ex. 8. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An Aeolian melody; "Voices from The River." This next melody is Jacmuse penned, developed from a wisp of an idea from a friend who grew up on the mighty Yukon River here in Alaska, who learned it from her grandmother. Example 8a. Cool ? Yea, 'A' minor all the way, pure diatonic lines can often take us all the way back. |

|

In theory, why so important? Only our relative major / minor grouping of pitches holds the diatonic ability to fully create the One / Four / Five chord progression, with each grouping of the three chords, being purely all major or all minor triads. Often termed the 'diatonic 3 and 3', these six triads / chords form the basis and chord progressions for most of our Americana songs, all through our whole spectrum of musical styles. |

This purity and consistency of musical color provides a perfect starting point for any degree of diatonic or non-diatonic development. Please examine and memorize if needed, the following barre chords. Example 8a. |

|

Where in the music? Just about everywhere. The One / Four / Five chord progression is historically among the most widely used in supporting our melodies. Nearly all children's songs, folk, bluegrass and country are One / Four / Five based, whereby each of the chords are all major or all minor. And the blues, even while altering the diatonic chord colors, is essentially a One / Four / Five chord progression. Variations to this diatonic perfection of the pitches? Endless. |

So, thus empowered, we simply use these organic, diatonic origins in creating so much of the music we love. We find ourselves again and again simply weaving the above six chords into progressions that support the ups and downs of the stories we are telling. For instrumental artists, we tell our stories through melody and support the melody with harmony. |

All of our American songs are based in either the major or minor tonality. As we stylistically morph from children's songs and folk, through blues, rock and pop towards jazz, this weave further evolves from this pure, seven pitch diatonic core by adding in additional pitches from our full compliment of 12. Like this. C D E G A C D E F G A B C C C# D D# E F F# G G# A A# B C |

The diatonic chord built on Six. As we might discern from the above discussions, the Six chord is a principle player in the American songbook. Diatonically a minor triad, the Six chord finds its way into all sorts of coolness in the Americana styles and songbook. |

Finding the triad on Six. In this next example, we evolve our C major scale into its arpeggio, respell it as its relative minor, 'A' natural minor, and then extract the pitches of our Six chord. Included in the example are some of the diatonic color tones commonly associated with Six. Example 9. |

|

|

Scale / arpeggio / chord. The triple crown of our modern theory and raw materials for creating and supporting our melodic lines, both written out and improvised. The Six triad / chord finds its way into our most common chord progressions. Here's a chart of its magics using numbers.

|

Diatonic Six evolves by non-diatonic alteration. Throughout the literature, the Six chord is mostly diatonic as a minor triad and often with an added seventh or ninth. With a bit of blues influence, Six often morphs towards becoming a dominant 7th or Five chord type. Once this transition is made, a few new options open up for an evolving artist. |

One common option is evolve Six from its diatonic minor chord into a dominant seventh or Five chord type. In this next idea we'll run the very common One / Six / Two / Five chord progression, first diatonically then with evolving the Six chord from a minor chord to dominant 7th, all in C major. Example 10. |

|

The crucial pitch. Notice the C# below the 'A7', in the third measure just above? In evolving our Six chord from minor into a dominant / Five chord type, we must raise the third of the chord by half step. Please examine the pitches. Example 10a. |

|

A 'C#', are we still in C major? Yes we are, we just borrowed the pitch C# from the key of D major. Really? Yep. Why D major? Well, to be theory correct, A7 is the diatonic dominant 7th / Five chord in D major yes? It sure is. So we in theory simply say we borrowed the pitch from D major. Is this common? It is, depending on musical style of course. In some blues and of course jazz, written out or not, this subtle evolution of the harmony on Six happens quite often. |

Why is this an evolution? Simply in that by morphing into a V7 chord, we gain a tritone interval within the chord. With this addition many new opportunities arise for the creative musician. Dominant harmony, and its ability to direct harmonic motion, is probably our most malleable component in morphing between the styles. |

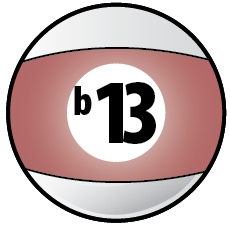

With dominant harmony, we might eventually add a ninth colortone. Here we're into blues and of course the funk styles. Once we're cool with V9, we can flat the nine for yet another new color. |

V7b9. While mostly a jazz color, theorywise our V7b9 chord has a fully diminished 7th chord in its upper structure. This new color, in theory, launches a new dimension to our palettes that we trace back to songs, to better understand the evolutions of the arts. Please examine the pitches for finding the 'b9.' Example 11. |

arpeggio degrees |

root / 1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

A 7 |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

. |

A 9 |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

B |

A 7b9 |

A |

C# |

E |

G |

Bb |

C# diminished 7th |

. |

C# |

E |

G |

Bb |

For jazz players it's game on. For once we get to this level of understanding and hearing the V7b9 / fully diminished 7th chords in the music, our options expand dramatically. Why? Well we can view the four pitches of the fully diminished 7th chord as four different leading tones to four different pairings of the relative major and minor key centers. |

We might not ever really modulate to those keys, but we might find something cool and borrow from there that makes our sound / art unique. Once the implication is in place that we might, then all of the possibilities of those keys now may come to bear on what we've got right in front of us. |

Couldn't they without the theory? Of course, but with the theory knowledge it becomes a structural evolution, thus an organically based development from diatonic triads to accessing multiple key center resources, to build a new upon the basics, increasing our challenges to master the complexities of what is available from our system of 12 tones, equal tempered tuned. |

If you not aspiring to the jazz world, all of this might just be mumbo jumbo say what ? As we used to say. But if you are jazz leaning, then this potential game changer becomes an organic theory portal to reach the highest of our Americana theoretical evolution to date. Of course through shedding, we still have to learn to hear it, shed through the possibilities and then make good art. |

For those so inclined and those in the know, this b9 transition helps us, at least in theory, to get our arms completely around the resource as we know it today. Which depending on many, many things ... can be a very, very cool place to hang out :) |

Review and onward. For most learners here, the crucial theory here is probably understanding the relationship between the major / minor aspect of our musical system. That we can locate our relative minor on the major sixth scale degree above our relative major root pitch, which sets just about everything in motion for this major / minor / duality, which is simply everywhere somewhere in our American musical styles. |

Locating the Aeolian mode / natural minor from Six, we locate the center of the natural minor environment. Motion to the diatonic Six chord and its morphing to a dominant chord is also all over the American sounds we love. As a catalyst to the upper reaches of our present theoretical evolution, the Six chord creates part of the portal to get there. |

“Nothing ever comes to one, that is worth having, except as the result of hard work.“ |

wiki ~ Booker T. Washington |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"Life is about creating yourself." |

wiki ~ Bob Dylan |

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |