~ interval study basics / exercises ~ ~ interval studies for the modern guitarist ~ |

|

|

Proximity to 'C.' Pick any other letter note than 'C.' How close, how far from 'C?' This 'how close ~ how far' proximity from one central pitch is the big picture we want to see now. We know that each of the Americana musical styles have their fave intervals; blues with 'b3' and '#4', bossa with 'major 9', the motion to Four to bring gospel love, in every conceivable configuration, style and genre. |

Tonal gravity. We as artists will craft this pitch proximity to one central note, as a key center, into a way to understanding the 'tension and release' dynamic in songs. With rhythms, it's how we can build laid back quiet or excitement, joy and sorrow, fulfillment and longing, all of our thoughts really, expressed musically. For each of the intervals has a different gravity, brings it's own color to the palette. |

Perfect. We as theorists are super blessed in our studies today in that in the old days, when the music theory principles we still enjoy today were being first laid down in stone, the word 'perfect' described anything that just couldn't get any better. Perfect meant perfect; that it'll get no better, or at least till 'something' better comes along, which in our music theory hasn't quite happened just yet. Same old pitches now as then and yet we're always making new musics too. |

Perfect organization. For 3000 years now give or take, the same organization of our pitches has held fast and works for bringing to life all of our Americana musics. What has changed is their tuning namely; just how precise we can tune the instruments that we could build. So lots of evolutions over the last 3000 years or so. |

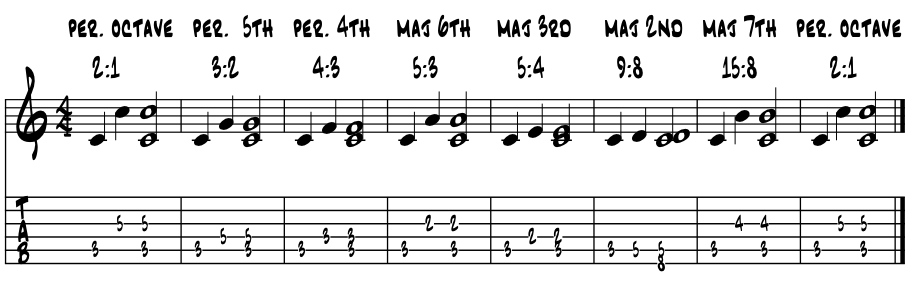

The three perfect intervals. Today's pitches were last fine tuned about 300 years ago, and have been creating all the Americana styles and genres of music we love ever since. When we rub different pitches together in music, the one's that are a 'perfect' interval apart from one another sound the best, they're 'easiest on the ears' (consonant) intervals of all the ones we have. There's three perfect intervals which in today's terms are most commonly identify by their name; perfect, and a number; '4th, 5th and 8', which is the octave interval, 'C up to C', a most perfect consonance of two different pitches sounded together. |

Quick review. We term them 'perfect' because they sound most consonant, 'easy on the ears' of all the intervals we have, and no surprise that Mother Nature bases our musical pitch perfection in all our natural earth sounds too. And if we mix in a little bit of measurable scientific mathematical method, understanding the musical perfection of the pitches and intervals is a snap. |

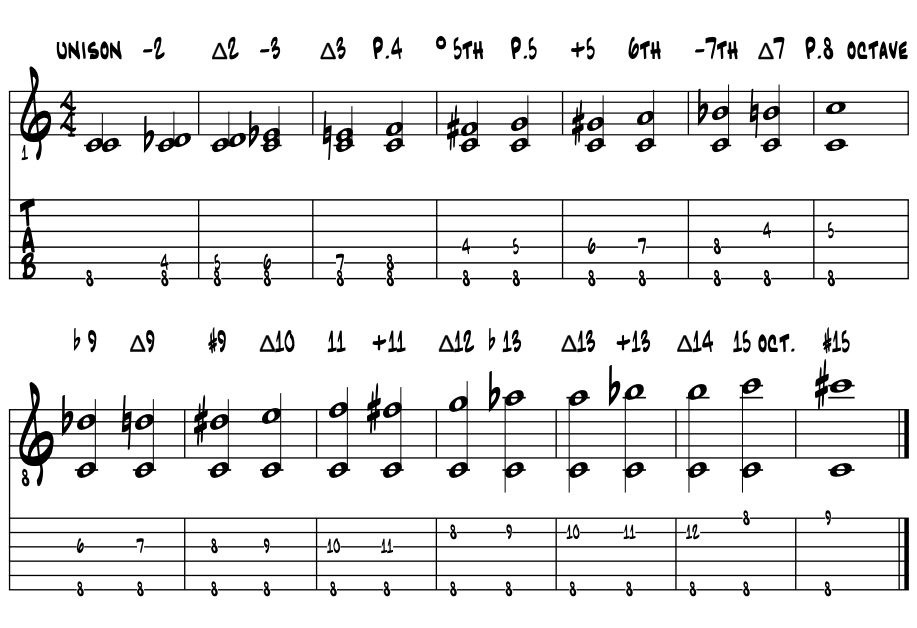

Labeling #'s. As music theorists, once any musical 'thing' has a name, it's just easier to include it in our conversations about the music we're examining or trying to create. So there's a few common ways to accurately name an interval and one is with numbers; we can generally use '1 through 8' for melody notes and for triads and chords we've '1 through 15' for the individual pitches of arpeggios, chords and their color tones. |

|

Major / minor / augmented / diminished. We further will designate each interval as measured from One, our root note, as being major, minor, augmented or diminished. These four 'qualities' help in accuracy for the nuances often created by half steps and define the aural quality of any interval or chord. Major and minor are the two essential halves of our core, while to augment is to man interval a wee bit larger while to diminish a wee bit smaller. These smaller adjustments are usually by a half step. C major 7 / A minor 9 / G7 aug 5 / B dim 7 / Bb13 |

Dissonance ~ inside / outside. Blues and jazz leaning cats here will appreciate this rhetoric of the intervals we use for theory untangling the puzzle pieces we love. Somewhere along the way, someone will point out to us that ... 'that' super cool new chord is called a 'V7b9' chord. And we'll use each one of the symbols; the V, 7 and b9, to understand the mix of colors combined to create its cool aural sound, strong pull of tonal gravity and corresponding powers of tension and release Each of the letters and numbers shape describe the intervals of each of the notes of this chord from the root note of a tonal / key center. |

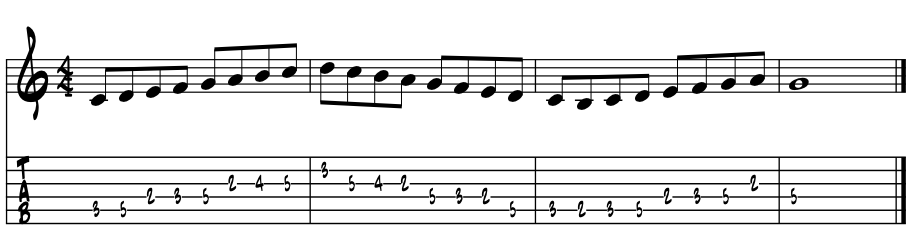

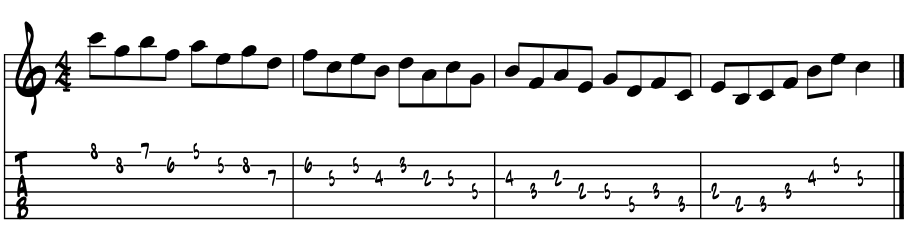

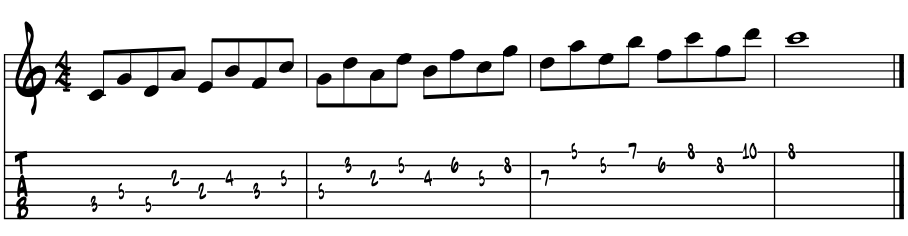

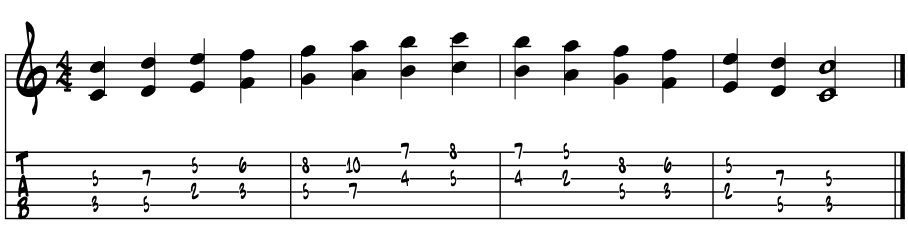

Learn each interval with a song. An easy way to learn an interval and it's relationship with its other pitches within a key center is to find a melody that features that interval in a memorable Americana melody. This was a suggestion from 'ear training' class at music school. Here's a few suggestions for our most popular songwriting intervals. The interval pitches are part of the first few notes of each song. Example a. |

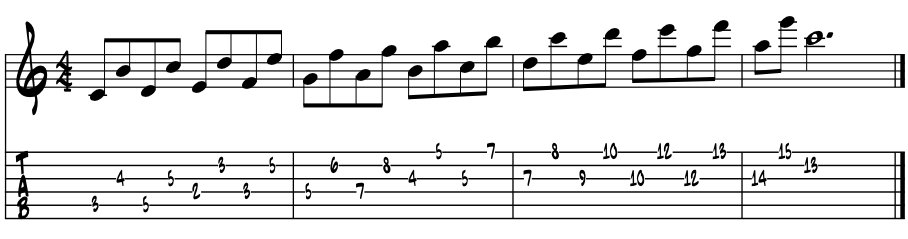

up a perfect 5th / minor |

|

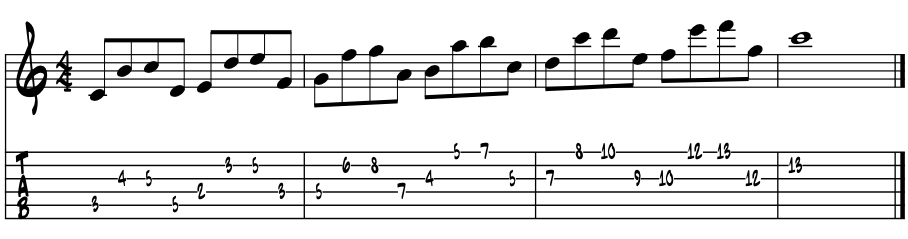

up a perfect 5th / major |

|

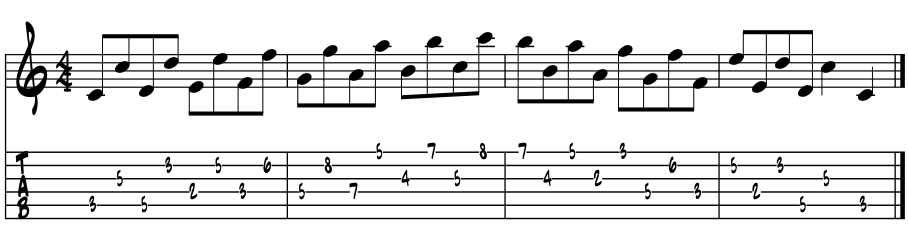

up a perfect 4th / major |

|

Advancing theorist. For the advanced theorist reading here, there's really just one idea for the general topic of this page; measuring and labeling the distance intervals between a root pitch and each greater degree of the chromatic scale. This entire exercise helps to prove up the perfect closure of our pitches. |

Simply that our 'groups of pitches' today are the perfectly closed loops of pitches from which we create our ideas of melody, harmony etc. Subbing for the term 'scale' to a certain extent, a 'group' includes multifaceted properties; diatonic positions and the intervals between them, that each pitch in a 'scale' brings to the conversation. |

These properties include; modes, shades of major / minor, arpeggios, colortones, 'parent scales' for phrases, intervals, sequences, soloing through chord changes. Our chosen group creates what is diatonic, thus establishing the boundaries of a select group of pitches. Combined we create a stabilizing perspective of the theory for venturing on beyond. |

The whole tamale. With the majority of melodies being created from the diatonic major scale group of pitches, an initial examination of the intervals within this group for emerging theorists just makes good sense. Continue here for a survey of our complete 12 tone resource. |

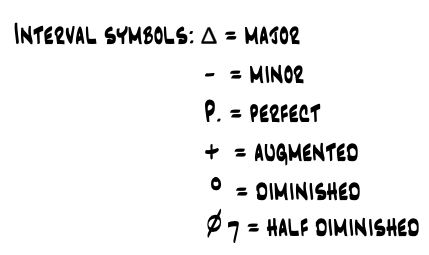

Common symbols. These symbols are used to identify the various aspects of our musical interval measurings. Example 1. |

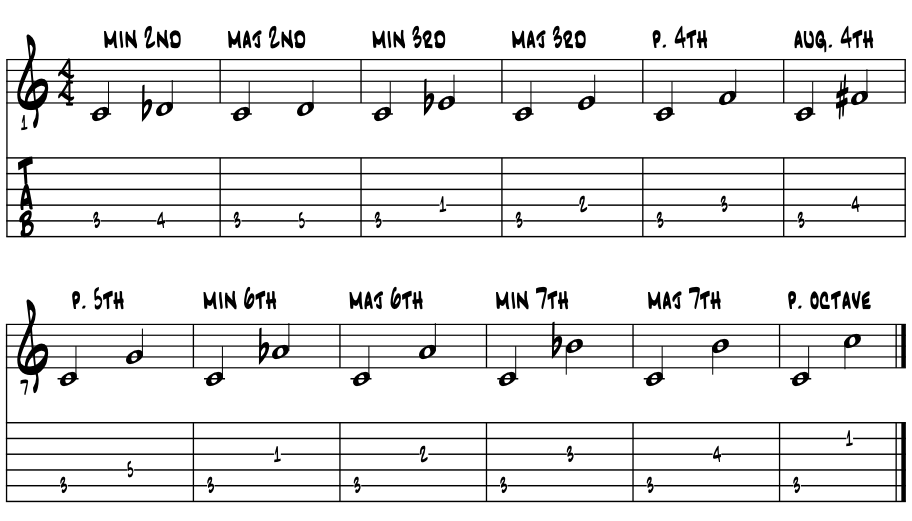

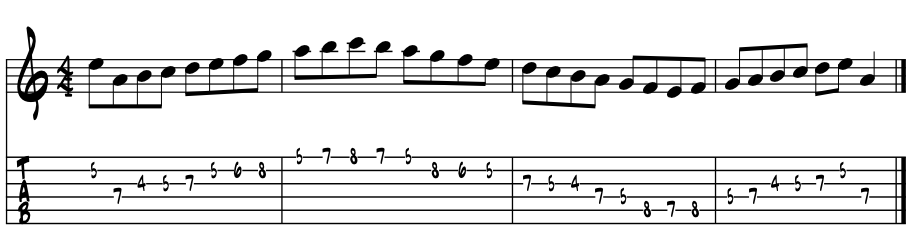

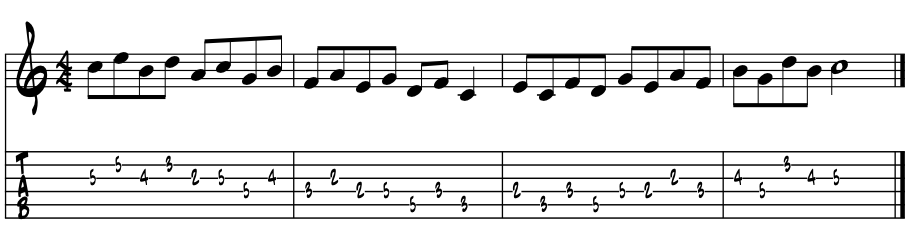

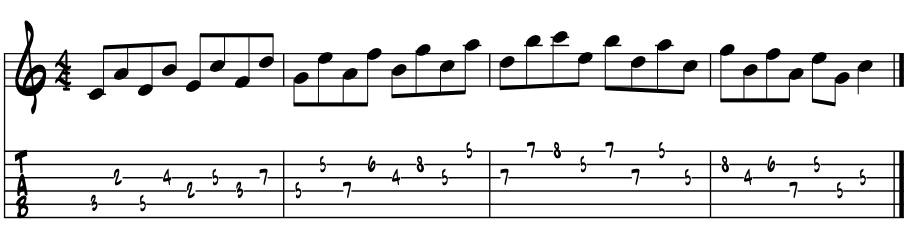

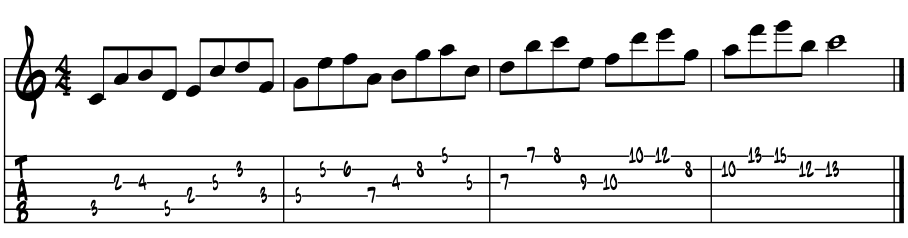

Survey the whole tamale. This next idea includes all of the intervals we'll commonly find in our musics all labeled generically. Used in creating the building blocks of scales, arpeggios and chords, each interval can have other names or numerical descriptions. It extends for two full octaves and includes each nook and cranny along the way. We term the intervals of the first octave 'simple.' Intervals of the second octave are said to be 'compound.' This sort of charting helps us get our arms completely around the resource. Example 2. |

|

Well that looks fairly complete. Some interesting fingerings yes? This all might be easier at the keyboard. If available, use the sustain pedal to sound, hear and sing along with each pairing. Also, these interval numbers are the ones used in creating a part of the main navigational chart for this book. Example 2a. |

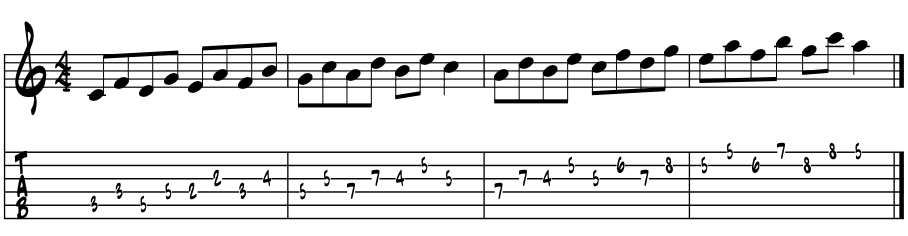

Chromatic scale ~ a 1/2 step ~ one fret ~ half step interval. A core center of the theoretical American musical universal is the 12 pitch loop of the chromatic scale. This symmetrical group of pitches is simply created by using only one interval; the half step. |

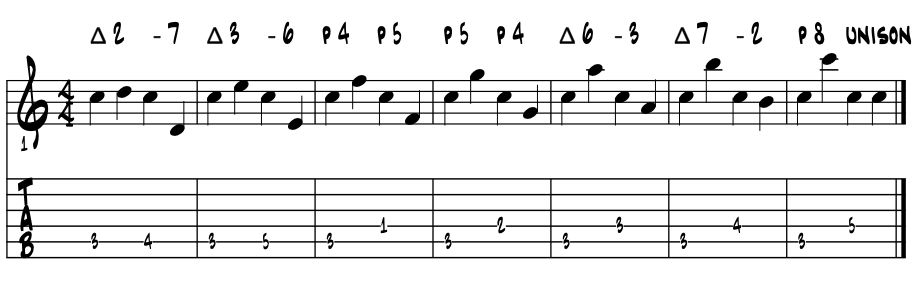

As theorists, we tend to want to slice and dice our musical intervals every which way and when we do, we want to try to label our dicing results with standard musical vocabulary. This labeling usually happens a couple of ways, which we often combine, to consistently dial in the aural sound with music theory terms. Thinking in 'C' major, building from the root pitch 'C.' Going by ' the numbers' as the sayin' go'ed. Example 3. |