~ a loop of _______ intervals ~ ~ half step through the tritone ~

|

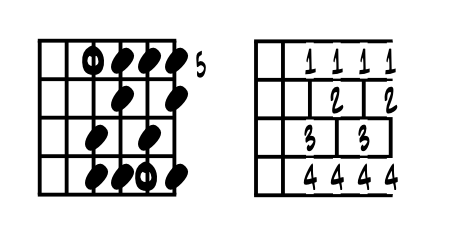

In a nutshell; loops of pitches. Simply to gain a complete sense of the perfect aural and theoretical closure of today's equal tempered pitches. We can achieve this understanding by creating a loop of pitches for each of the intervals found within the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. To begin this 'loops' study, find the looping pattern of two / three black keys on the piano. Same '2/3' key pattern as on any piano. Example 1. |

|

Get hip to this and you're golden. Catch the looping pattern of the piano's black keys ... ? Super set in stone for a long time now, it lays out the 12 pitches by half step. Simply stated, that near everything we do with our pitches and theory can be shaped into a loop. And if we keep whatever pattern of intervals or formula consistent and going on long enough, it'll always close back on its starting point. Always? Yea pretty seamless here and kinda set in stone :) |

This closure works with the intervals, scales, arpeggios, chord pitches, rhythmic patterns, even into the extended patterning of combining more than one interval or element. Any of our musical components, that can be represented by letter or number, will adhere to this idea 'closed loops.' |

Overview: Building upon our first idea of a silent architectural structure, this idea of 'loops of pitches' is really an essential concept within the core structure / philosophy of this text. Nearly all of the discussions throughout this text will be based, refer to or be centered around this idea, of a perfectly closed loop of pitches. |

This idea of closure not only includes our pitches, intervals, scales, arpeggios, chords, forms and such but will also apply to the theoretical, artistic and stylistic discussions as well. For it just seems that the closure of 'anything and everything', or just a balance even, is what our curious human minds tend to seek. Is this why there's all these 'Ying ~ Yang' spheres are about us ? :) |

|

Once this 'loops' foundation is in place, what we gain is an ingrained ability to better understand how smaller sub sets exist within larger loops. These subsets become the specific groups of pitches with which we create the Americana musical sounds we love. Loops within a loop. A neat thing about perfect closure is that we'll intuitively sense music sounds and colors as unique, yet still of the common, organic source of pitches. All bounded by the sense of tonal gravity, Music's love affair with Time. |

One of the most fascinating aspects of the theoretical perfection, created by filtering Pythagorus' original cycle of fifths through equal temper tuning, is in its ability to be sliced, diced, blended, boiled and baked ... oven, broiled or pan fried, yet artistically come out nicely balanced, with its original structures intact enough to recognize. |

And like the cat that somehow always lands on its feet, our Americana musics, and its extensive reliance of rote learning and improvisations, require a thorough facility of thought and technique to perform. An unbreakable loop of pitches and playing by heart merge to become the way of crafting our stories of life into songs. |

| What follows here. The following discussions explore our intervals within an equal temper chromatic scale, to prove up on the idea of its perfect closure of 12 pitches jumbled every which way. We take each interval in turn, as it is extracted from the chromatic scale, and create symmetrical loops based solely on each interval. Thus, we will not mix intervals together to create additional loops. That joy is saved for a later chapter titled groups of pitches ... (from which we create our melodic ideas.) |

| As we move through the intervals and create their various loops here, we'll still run into many different configurations of the pitches, many stylistic ideas and lots of new vocabulary words, many of which can lead us off to other discussions, simply with a click on those magical letters and text we term a hyperlink. |

Beginning theorists. If you're just getting into this Medusa head of music theory, when we talk musical numbers, simply counting up on our fingers and toes can help create correct solutions. We never go past 15 :) And while there's a vast degree of projection in our musical intervals, please don't let it get in the way of your moving forward. You can learn the fine print if and when you need it, as so much of our learning right here simply uses the numbers one through eight. |

|

Even when we associate pitch letter names with numerical intervals, a lot can still be counted upon our fingers and toes. This is how so many of us learned our numbers when first starting out as little peeps and it'll work just as fine and dandy today too as music theory scholars. Review the notation symbols if needed, and continue or learn to read notation here if you're so inclined. It's easy, and opens up an unlimited library of music for study and performance. |

"It always seems impossible until it's done." |

wiki ~ Nelson Mandela |

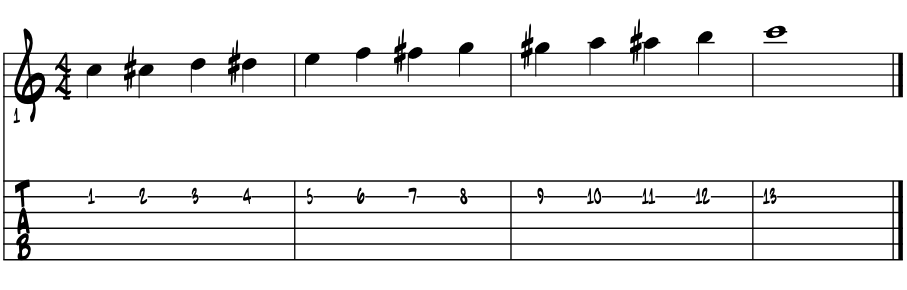

The chromatic scale; by half steps, augmented unison and minor second interval depending. While as guitarists we can always still get between any pitches by bending a string or two, in theory the smallest theoretical division of equal temper tuning is the interval of a half step. This translates to one fret on our guitars and creates consecutive half steps of the chromatic scale. Here is the loop of pitch letter names. Looks familiar yes? The historical, organic origins of this loop is the topic of our discussions titled silent architecture. Please examine the pitches of the chromatic scale. Example 1. |

C |

C# |

D |

Eb |

E |

F |

F# |

G |

Ab |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

We have closure, C up an octave to C. Sharps and flats in the same line? That is bad musical form n'est-ce pas? It is. In the theory, we follow a song's key signature to designate pitch letter names. Rare if ever do we see #'s and b's in a written line. The example above mixes pitch letter name accidentals to introduce here the term enharmonic equivalents. One pitch with two letter designations, which is ultimately determined by key signature within a song. Here is the sound of the above group, now notated correctly as an ascending melodic line. Do sing right along. Ex. 1a. |

|

How were your vocal pitches? Try it again. Every day a couple of times for a month or so and you'll have it. |

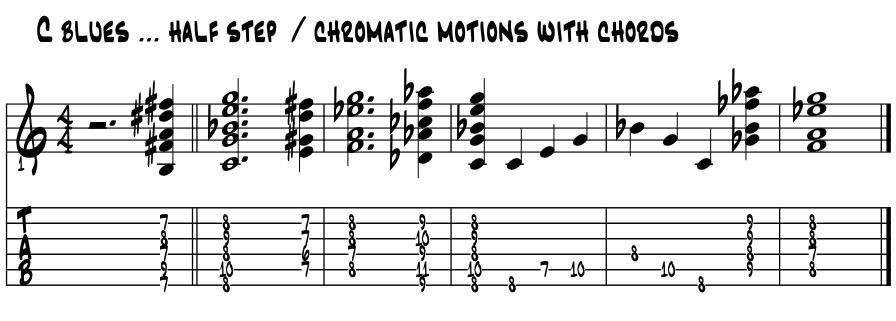

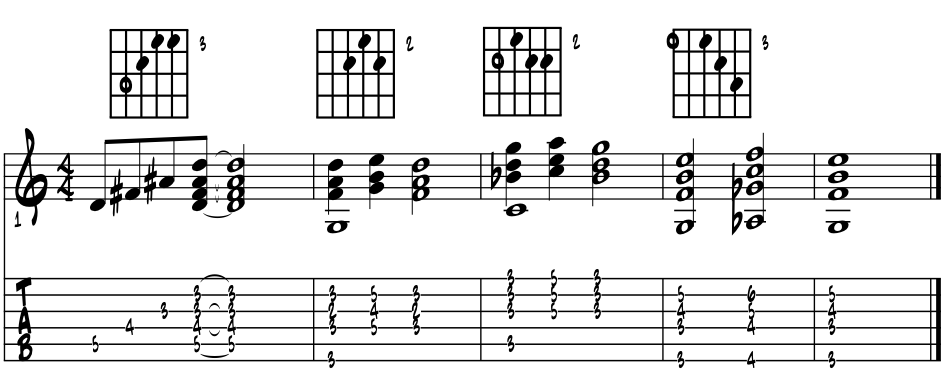

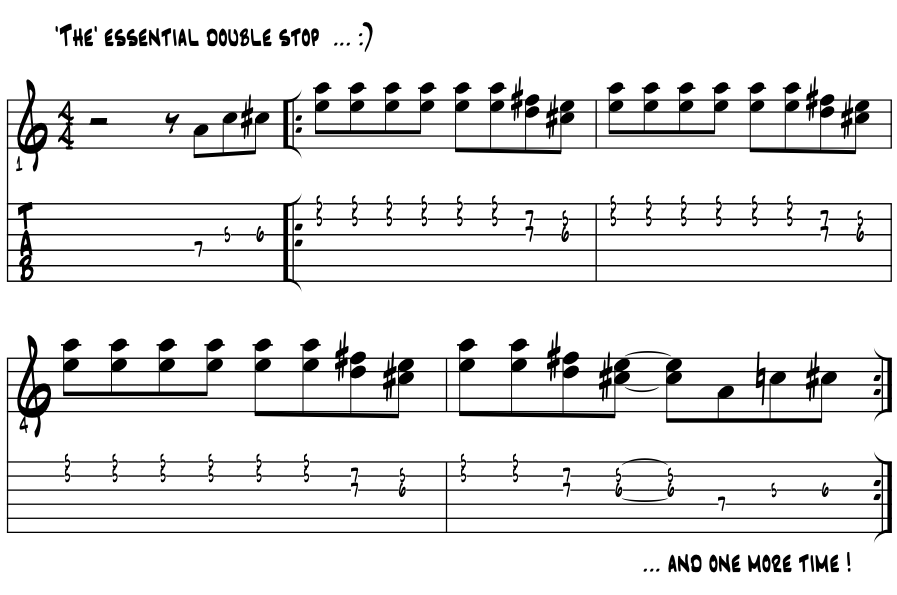

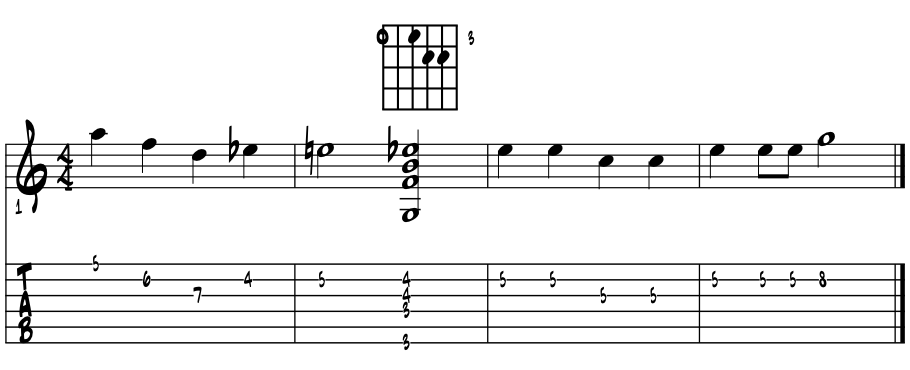

Where in the music. Super rare in folk and mostly a blues / jazz color, and most often in small bits we term chromatic enhancement. Where we 'surround' other pitches with notes a half step away. Charlie Parker was arguably the first King of Chromatic Enhancement. Once his music came over the airwaves in the 1940's, everybody considered spicing up there own ideas with a bit of the chromatic color. The half step lead in for blues and jazz leaning cats is really an absolutely essential lick and trick, especially for the 12 / 8 shuffle and 2 and 4 swing feels, so everything Americana really. With any movable chords, the half step motion can totally 'bring the swing' in a hurry. Here's some blues chords with a half step lead in motion from below then above. Motion from One to Four, 'C' blues. Example 1b. |

While this last idea might be cumbersome artistically, getting this half step motion under the fingers is a big step, especially working it with a metronome in time. |

Metalists move by half step an awful lot too, especially as their tempos brighten. Half step = sleeker = faster :) The 'melismatic vocalise' of today's pop stars have a certain quality of chromaticism, especially with the gospel like blue notes, deftly woven into diatonic tunes written in a major key. These blue notes are the half steps between the diatonic tones. Enhancing diatonic folk melodies with blues brings the gospel. |

So while chromaticism can really be anywhere in the Americana sounds, there's very little totally 'chromatic' music. At least not on the radio and popular songs etc. The trick is to be able to hear the chromatics within the diatonic realm, it can make things sound just a wee bit off key, from within a key center, created by the seven pitches of the relative major / minor group. Again and forgive me here for redundancy, but this 'off key quality within the diatonic' brings the essential blues hue, a big thread in our Americana weave of musics. |

And once dialed in, we'll spice up our own ideas with this ultra simple yet way hip technique. Surely strive long term to develop the ability to fairly accurately sing a chromatic scale. While it may take some time to master, it'll surely do wonders for your overall musical abilities and help to dial in your built in stereo radar. |

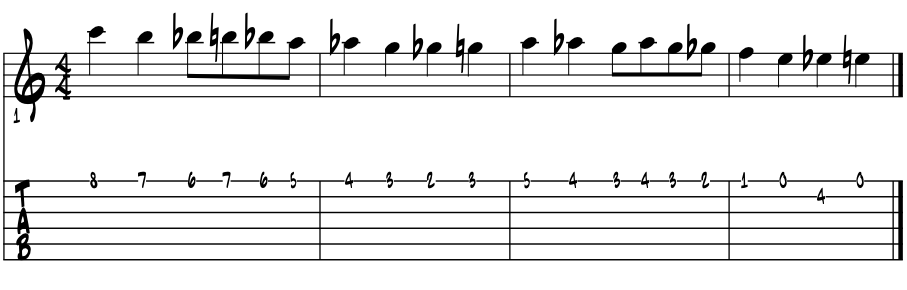

A chromatic melody ... of sorts. There is one familiar melody of a mostly chromatic quality that we all might remember from way back. To me it is from the olden days, an old carnival melody that turns out to be a really incredibly powerful work by one Julius Fucik. Dig a lick of the main theme of "Entry Of The Gladiators." Do notice the use of flats and naturals as we half step our way in this descending melodic idea. Example 1b. |

|

Quotable? Know the line? Cool. Oftentimes in the improvisational aspects of American music players will play a snippet of a melody of a song and place it into another tune. Players simply call this 'quoting.' This type of improvisational play will usually bring smiles to those in the know. And this last melody is a rather quotable lick and easy to fit in any key, as it'll surely start equally fine on any of our 12 pitches. |

Loops / a whole step / major second universe. So ... two half steps combined equal one whole step yes? And a whole step and a major second interval are one and the same? Yes to both and all is groovy here in theoryville. For surely they are the same here, there and everywhere. The whole step or whole tone division of the octave creates the whole tone scale. |

By its consistent construction of just one interval, the whole step, we can also term the loop as being symmetrical. This is mostly a jazz and classical color, which finds its way in rare occasions into the pop and the blues sounds, most often as an augmented triad / chordal color built on V7 and tonic One too. Six whole steps to close the loop. 'C' whole tone scale. Example 2. |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

F# |

. |

G# |

. |

A# |

. |

C |

We have closure, C up an octave to C, but we only were able to use six of our twelve pitches in the loop. Wonder if the other six will make a complete whole tone scale too? Example 2a. |

|

. |

Db |

. |

Eb |

. |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

. |

Db |

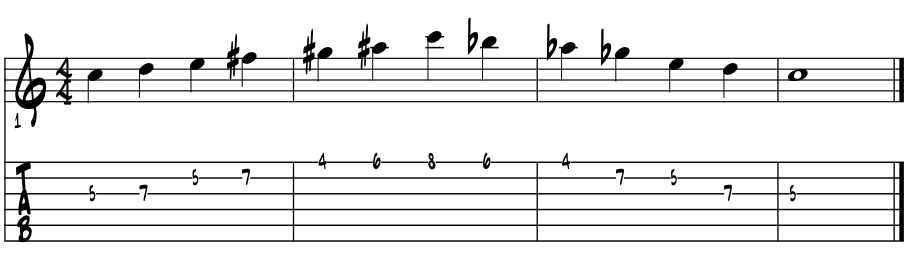

We have closure again ... imagine that :) 'Db' up an octave to 'Db' and sure enough, our other six pitches create a second whole tone scale. So only two different whole tone loops eh? Yep, only two. And with the symmetrical interval formula, can we start on any of the pitches in a group and create the exact same loop of pitches? Absolutely. Any slice and dice will work. Here is the sound of the 'C' whole tone scale. Example 2b. |

|

Simply up and down the whole tone color. It is a classic sound peppered rather sparingly into the Americana styles. Most common use? Probably adding the whole tone color to V7 in a minor blues. Also, augmenting a tonic chord then moving to IV or ii-7. |

The whole tone color is also fairly common as part of the #11 in jazz chords. But these are harmonic uses and not melodic. It is a tough scale to tame and disguise, but a refreshing and essential color when we find the right spot for it. |

For guitar, whole tone scale shape. This scale shape is fairly common, especially on the top four strings, and really gets at the whole tone color in a hurry. There are a couple of augmented chords within this shape and their corresponding arpeggios. A bit of a stretch at first, just gradually find your own comfortable fingering. The one included is fairly common. |

Positioning this shape at the second fret generally makes for the 'C' whole tone scale, thus the open circles on the 'C' pitches in the diagram below on the left. As the theory pointed out just above, this positioning of the scale shape at the second fret also contains the pitches of the 'D, E, F# / Gb, G# / Ab' and the 'A# / Bb' whole tone groups of pitches. Example 2c. |

pitches |

fingering |

|

|

Do note, that the 'big and bold' nature of a graphic shapes generally denoting 'grande essential potential.' :) Lovely thing about a picture of these scale shape diagrams is that oftentimes, some easy licks and fingerings pop right out. The 2/1 - 4/2 on the 5th and 4th strings. The 1/1 - 3/3 on the 3rd and second strings and surely the 1/1 to 3/2 whole step motion on top. |

Again the idea that with the whole tone color, thanks to our guitar's built in theoretical organization, we can move any idea up and down by whole step and remain theoretically correct pitchwise, within our key center or chord change of the moment. |

Jazz players will often take advantage of this physical nature to create an idea with two or three pitches, a melodic cell, and move it up or down the neck by whole steps. So if you're playing a tune in 'G' and finding things in second position, the whole step motion helps us run the thing right up to the top at the 12th fret' and resume our 'G' musings with a new scale shape. |

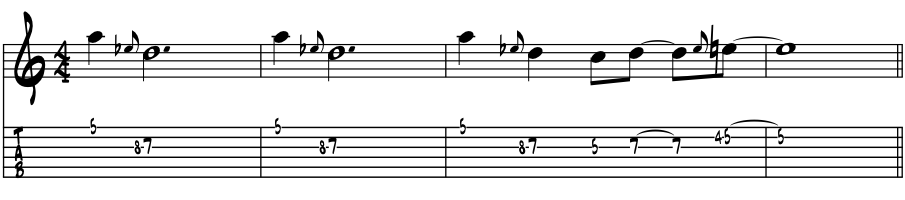

A whole tone idea. Here is a fairly common use of the whole tone color when used over dominant harmony in a resolving nature. Thinking Two / Five (V7+5) / One in 'C' major. We use the augmented 5th, 'Eb', as a half step motion moving up to 'E'. The opening of this idea, the descending 'D' minor triad arpeggio, with a touch of the chromatic, was inspired by jazz guitarist Jimmy Bruno. Example 2d. |

|

|

Please remember that with the symmetrical whole tone color, and thanks to our guitar's theoretical organization, we can move any idea up and down by whole step and remain theoretically correct within our key center of the moment. Click to the 'more things wholetone' page to continue your explorations of this distinctive color. |

Loops ~ the minor third / diminished arpeggios. Adding a half and whole step together creates the minor third interval. Beloved by blues artists as the blue 3rd, the minor third is a crucial link to the blues roots at the core of the Americana sounds. It's the third of the minor triad, and as we'll see with a minor third cycle, stacking the pitches of the minor third interval into a four note arpeggio creates one truly great accelerator of our local harmonic universe; the fully diminished seventh chord. Triad and 7th chord. Ex. 3. All of this and we still retain our perfect loop to boot. But you knew that was going to happen right? Perfect loop closure, each and every time. Example 3a. |

C |

. |

. |

Eb |

. |

. |

Gb |

. |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

We have closure, 'C' up an octave to 'C', but we only were able to use four of our 12 pitches. Wonder if the other eight will make two more complete cycles of four pitches, as based on the minor third interval? Ex. 3b. |

C |

. |

. |

Eb |

. |

. |

Gb |

. |

. |

A |

. |

. |

C |

. |

Db |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

G |

. |

. |

Bb |

. |

. |

Db |

. |

. |

D |

. |

F |

. |

. |

Ab |

. |

. |

B |

. |

D |

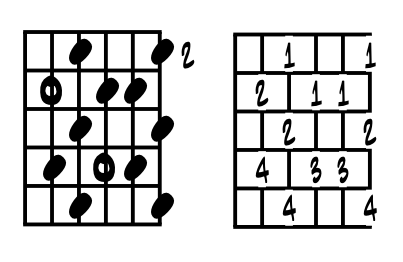

Three for three and we have closure. And sure enough, our other eight pitches minor 3rd up to create two more complete, diminished seventh arpeggios. Are three unique diminished arpeggios the max? Pretty much; 3 arpeggios x 4 pitches = 12. And we've used up all of our our pitches. Dig the sounds of symmetry. Example 3b. |

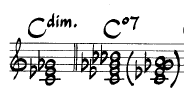

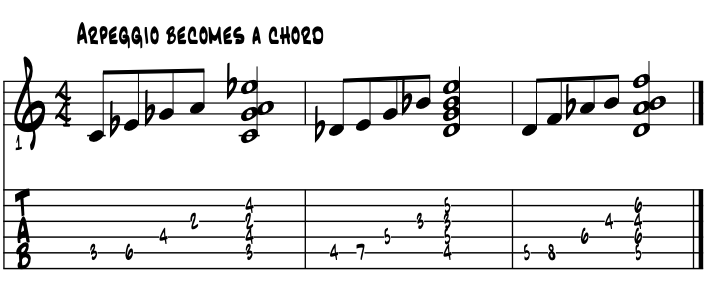

OK with playing this lick? It's a bit of a different motion. Can we stack these pitches into diminished chords? Getting a bit ahead of ourselves here but yes, arpeggio pitches stacked and sounded together become chords. So three different diminished chords covers them all? Yep, just three, as the perfect symmetry allows any pitch to assume the root pitch responsibilities. Example 3c. |

So both of these last few ideas, whole tone and diminished, take advantage of the interval symmetry of the pitches as well as physical symmetry available on guitars. This basic idea of symmetrical motion can play a HUGE part in one's musical evolution. How so? |

Simply in that by learning one movable idea, with a set fingering pattern, we can then freely move this shape of pitches up, down and around, vertical, horizontal, even move patterns within patterns. Limitless combinations, like snowflakes. And for the improvising artist, always allowing for the mood of that day to shape the ideas. |

|

Players and theorists often call these sorts of directional ideas as being in 'parallel motion', or motion created with a 'constant structure', both artistic techniques that move the same chord shape up and down the neck, across the strings or both combined. In doing so we can accelerate the sense of forward motion and even stretch the pull of the swing a wee bit more. |

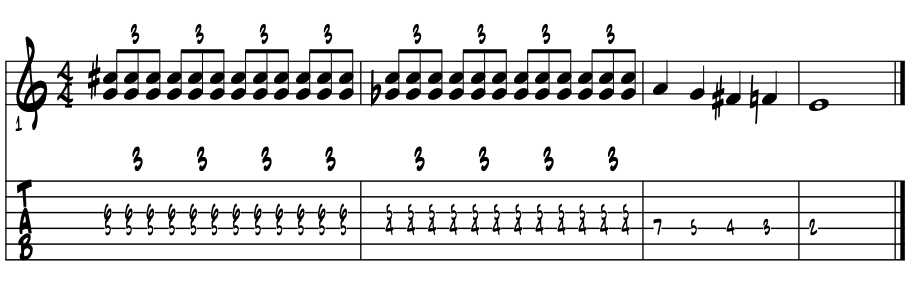

Diminished scale shape. This next scale shape is probably the most efficient of our diminished colors and lucky for us, it also bolts right up into the four finger / four fret technique potential. In initially learning this shape, it surely helps to locate the four different associated root pitches and where they are on each of the four strings within the overall shape. |

In this next idea we identify one root pitch, 'G', with the open circle. Puzzle out the whereabouts of the other three related minor 3rd intervals; the 'Bb, Db and E' within the shape, and they'll be yours forever. Ex. 3e. |

pitches |

fingering |

Got this under some fingers? See the diminished chord shape of the '1 2 1 2' on the four adjacent strings? That can be a keeper :) |

Old time blues. This next idea goes way back in the Americana sounds, to some of our earliest recordings. It's funny because I've heard this lick for years but never associated it with the minor 3rd / diminished chord theory, perhaps because we so often only here this much of the pitches / tritone interval. |

Not really being an early blues style player myself, I was able to confirm this use of the diminished color with the established Americana guitarist Paul Asbell, who said the diminished color in this spot is not unusual at all. Here's the lick. Example 3f. |

|

Sound familiar? Not uncommon in original blues guitar. This lick becomes part of the evolutionary process; for if you can 'accept' this sound, make it work, in time, in your music, it'll help in coming to terms with all the diminished colors, the blues rub and V7b9. |

So learn it here if needed, transpose it a bit on different string sets and find a spot in your own music to fit it in. In doing so you hitch your wagon up to the historical blues on the Americana musical highway, joining up with a zillion variations of this central musical idea. |

Fast Four / Tritone interval. Probably getting ahead of things a wee bit, as we'll meet up with the tritone a bit further down this page, but just too easy theorywise not to add some pitches to the last idea and find something new. So the 'fast Four' simply implies motion to the Four chord in the second bar of a 12 bar blues. Jazzer's include this motion rather regularly as it gives us yet another option for soloing as the harmony shapes and directs the line. Any slower tempo, grinding blues number should feature this 'fast Four' also. |

Well the trick of it is that in our early blues sounds, the Four chord was oftentimes also a diminished chord. A Seattle player Ken Carlson passed this along down at Emerald City Guitars one day. Here's a melodic idea running the diminished scale / minor 3rds idea over the Four chord. Thinking 12 bar blues. Example 3g. |

Combining the old and the new. So we took the old two pitch tritone blues style idea and theoretically built the pitches into the Four chord for a 'fast Four' idea. Just to jazz it up ? Yep, a motion leaning towards a common jazz style event. In discovering these types of relationships between the pitches and components, the music theory evolves with our musical style. |

Understanding what we hear in the music helps generate new ideas, a core benefit of doing the work to learn and understand its silent architecture foundations. Thus empowered, we can forever self propel our own lifetime learning process and development, simply by having an organic, understanding of our music theory. Organic? Organic music theory? Or ... music theory from its organic origins? Yea, that's better :) |

Loops / major third / augmented triad. Adding two whole steps together creates the major third interval. Among the most important interval we have, the major third defines the major triad, the core building block of so many songs in our library of AmerAfroEuroLatin music. Do sing along with this bit of melody, for the last pitch E is the major 3rd above the C, our tonic pitch. There's a lot of Americana history in this song. Ex 4. |

History. So, know this opening lick? Titled as 'Amazing Grace', turns out that those are the words, as the melody comes from a song titled 'New Britain.' Hard to describe the impact that this song has had on Americana over the last century or so. Suffice to say that it's a classy tune to play, everyone in the room should know it and, that in itself, is reason enough to learn it. And if you're thinking of getting into bagpipes, 'Amazing Grace' is a bag piper's standard song. |

|

A loop of major thirds. Creating a loop of major thirds, we create a whole tone type character sound of the augmented major triad, by nature of its augmented fifth. Please examine the pitches, Example 4a. |

C |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

. |

G# |

. |

. |

. |

C |

Again the closure, 'C' up an octave to 'C', but we only were able to use three of our 12 pitches. Let's try finding the pitches in between the 'C' augmented triad, starting up a whole step up from 'C.' Example 4b. |

. |

. |

D |

. |

. |

. |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

A# |

. |

C |

Adding things together. Again, after three / major 3rd intervals, the closure, 'D' up an octave to 'D.' Again we only were able to use three of our 12 pitches. Let's add the two groupings from above together and see what shakes. Example 4c. |

C |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

. |

G# |

. |

. |

. |

C |

. |

. |

D |

. |

. |

. |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

A# |

. |

C |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

F# |

. |

G# |

. |

A# |

. |

C |

Theory coolness emerges when we combine the two augmented triads into creating the whole tone scale. Is this the same one we created above with the whole step interval? 'Tis is indeed. So, we've still only used six of our 12 pitches. Any guesses as to what we'll can create with the other six pitches, using the same major third interval as our building block? Example 4d. |

Db |

. |

. |

. |

F |

. |

. |

. |

A |

. |

. |

. |

Db |

. |

. |

Eb |

. |

. |

. |

G |

. |

. |

. |

B |

. |

Eb |

. |

Db |

. |

Eb |

. |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

. |

Db |

Well, same results yes? Hmm ... Again, no matter how we slice and dice our pitches, the closure is always perfect. So combining our two whole tone scales, each consisting of six pitches, we create yet again the granddaddy of them all, the 12 pitch chromatic scale. Example 4e. |

C |

. |

D |

. |

E |

. |

F# |

. |

G# |

. |

A# |

. |

C |

. |

Db |

. |

Eb |

. |

F |

. |

G |

. |

A |

. |

B |

. |

Db |

C |

Db |

D |

Eb |

E |

F |

F# |

G |

Ab |

A |

Bb |

B |

C |

Db ...

|

So four possible augmented triads? Combining the above major 3rd interval theory, we find that we max out at four unique augmented triads, before the cycle perfectly loops back to its starting point to begin yet again. We can expand our resource from just these four augmented triads to include all of our possible 12, simply by juxtaposing the pitches of each chord. For the interval symmetry allows for each pitch of the augmented triad to fully function as its root pitch. |

Surely we can also build each of these augmented triads from each of the 12 pitches. That idea lives in the 'anything from anywhere' concept. What is unique here is how each pitch of the triad can function as the root of the chord. What other interval colors and chords might have this multiple root possibility? For every Yin must have its Yang n'est ce-pas? For each major there's a minor yes? Hint; think of symmetrical structures and read on ! |

Three for one. Thanks to our perfect theoretical closure and interval symmetry, each of the pitches of these major augmented triads can assume the root function of the chord. So while we can still have the various inversions of the augmented triad, we also gain the potential of the inversions becoming root position chords. How cool is that! Examine the three possibilities with pitches identified from each chord root. Ex. 4f. |

C |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

. |

G# |

. |

. |

. |

. |

E |

. |

. |

. |

G# |

. |

. |

. |

B# ( C ) |

. |

. |

. |

. |

G# |

. |

. |

. |

B# |

. |

. |

. |

D## ( E ) |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Root motion / inversions. While root motion of the chords / bassline is always paramount in telling the tale of a tune, inversions help to give composers a variety of shading of emotional hues of aural color as well as varying degrees of the forward motion of tonal gravity. |

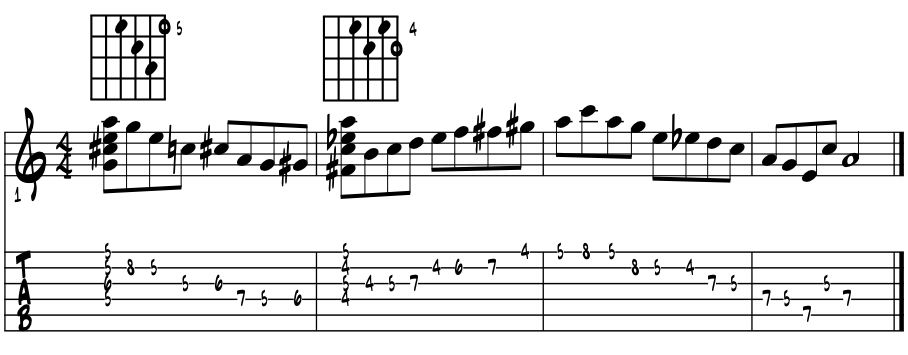

This augmented color is a rare element and mostly a jazz color nowadays, yet knowledge of it helps recognition when we hear it. Surely it could be part of a composers aural resource. Here is a chart of the four different augmented triads and their eventual perfect closure. The looping pitches align and close. Example 4g. |

|

Theorists, we have closure. Are four unique augmented arpeggios the max? Sure is, the math of it is 4 x 3 = 12, so we've used up all of our 12 pitches. Augmented triad plus 7th? 9th? Absolutely. Two things in the symmetry here; cool chromatic angles and the 'C's in the three of the corners a reminder of perfect closure of any loop of pitches. Just digging the 'Escher-like' closure properties of equal temper tuning and of the oftentimes perfect symmetry within its realms. Pure pitch magic. |

|

On the fretboard, the 'Esher' quality of the chart shows right up in the pitches and tab fingerings for the augmented triad. Jazz players take advantage of this type of motion. Metalists too with their sweep picking magic. Here is its sound. Example 4h. |

In the music. Two rather common uses of the augmented triad come right up. For the blues leaning artists, we so very often hear the augmented triad as a Five chord in the blues, setting up the return to the top and the return of the tonic One chord. The augmented 5th pitch of the dominant chord is the blue, minor third of the target key, tonic chord etc., so a common tone. |

Augmented triad. Here is the fairly common use of an augmented Five chord, setting up the top in a 12 bar blues. So, 'D +5 to G7.' Example 4i. |

Turnaround chord. The 'D' augmented chord in the first bar of the above idea is also used throughout the song as the last chord of the turnaround to the top of the 12 bar blues cycle. Quite effective in resettling things. |

Check out The Allman Brothers cover of the essential blues standard, T. Bone Walker's "Stormy Monday", just a classic take on a classic song. One of many, but surely a memorable arrangement to a venerable song. |

|

For hipster popsters, surely dig out, cue up and enjoy The Beatles' "Oh Darling." For right from the top, the first chord in the arrangement, is the augmented triad. Really gets our attention and sets the tone. |

|

Composing with the augmented triad. Jazz artists probably noticed the link to Coltrane's "Giant Steps" just above. This song is based on making the pitches of an augmented triad the key centers in a song. That its melody is a 'joyous modern gospel of half notes', disguises the complex coolness of its silent structure. That is, until the blowing. |

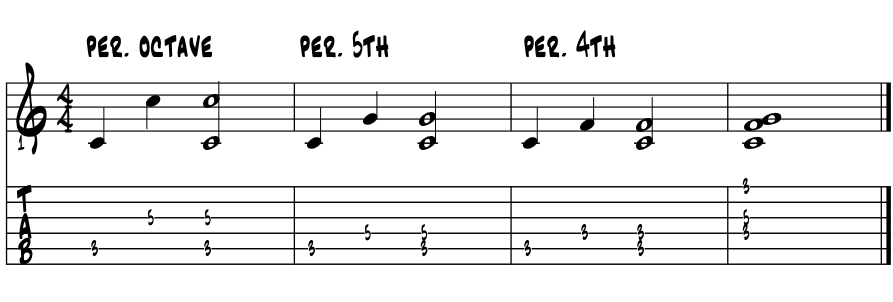

The perfect fourth. We get to our next musical interval simply by enlarging the major third by half step, creating the perfect fourth. Why perfect? Quality / purity of sound. After the perfect octave of 2:1, then the perfect 5th at 3:2, then the perfect 4th as 4:3. Three 'perfect' intervals and their ratios, no more no less ... in terms of the pure theory lingo of functional harmony. Example 5.

|

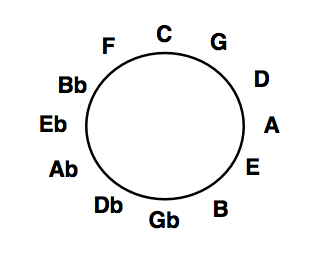

Ah ... the sounds of perfection :) So in proving up the closure of the perfect fourth interval, we need to use all of our 12 letter name pitches. And thanks to our modern equal temper tuning, their actual sound closes in tune too. The easy solution for proof of closure is the cycle of fifth's, but in this example, read from the top pitch 'C' to the left, or counterclockwise. |

Jazz players often term this counterclockwise motion backpedaling, as they see it in the root motions of chord progressions in countless jazz standard songs. From 'C' at 12 o'clock top to the left to 'F / Bb' etc. Example 5a. |

|

Surely this backpedaling can start on any of the letter names pitches, major or minor key right? Spin this now ancient depiction any old way and it'll still work just fine. Find a song, find its key note and locate this pitch on the cycle pic. Then examine the root pitches of the chords is your song and see how they line up with the letters of the circle. |

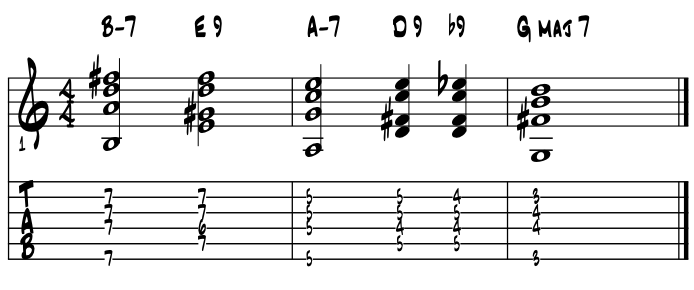

Need some changes to examine? Here's the ever essential jazzy 3 / 6 / 2 / 5 / 1 turnaround extravaganza from the 1940 hit "Polka Dots And Moonbeams." Thinking in 'G' major. Example 5b. |

So by making the letter 'G' our target note, we simply backpedal by perfect 4th, click by click from 'B' to arrive at 'G.' Quite common in lots of songs, 'Polka Dots' was a popular hit for many great artists. |

|

Graphic is perfect for shedding. Players often like to shed musical ideas through the cycle of 12 keys as represented above. And while mostly a jazz thing, musicians of all musical styles may benefit from the process. Even if we do it just a couple of times, it's amazing how this simple exercise gets us to the distant places in the resources, that then become not so distant. |

And of course we'll never know when we might need something from the far reaches. So pick an easy idea, such as major triads, and use the cycle graphic as a visual aid to keep track of things. Use the pitches of the cycle as the roots of the triads. It's fun, challenging of course, and pays big benefits depending on your artistic directions now and forever into the future. |

Wedding bells. Among the historically most recognizable melodic ideas we have, centered around the interval of a perfect fourth, is from composer Richard Wagner's 'Wedding March.' Sing along with these pitches with the words ... 'here comes the bride.' Up a 4th, then up a 5th, then up a 4th, then back to the beginning Five / One to close the line. Here written in 'C' major. Example 5c. |

|

All kinds of perfection of sound in this melody. Learn it here if need be, especially if you aspire to play these wonderful gigs. Extra dramatic and attention getting when sounded 'in octaves', and an easy song to create a chord melody arrangement too :) |

12 key cycle / melodic idea. Let's run just the first motif of the last melody through the cycle of fourths as described above. Play this line completely through and you'll have covered an important component part of each of our 12 major keys, the Five / One essential cadential motion. Example 5d. |

12 key cycle / major triads. Oh well while we're at it, we might as well run the major triads too, as also suggested above. Do dig the exercise nature of the fingerings as we move across and up the strings. Once comfortable with the idea, perhaps try a quarter note triplet rhythm. Example 5e. |

Jazz players ~ triads are king. Why? Well in traditional jazz improv, artists are soloing through many many different chord changes and the triad is basis of them all. For aspiring jazzers, running triads is a good exercise. Bass players too, for in all the styles the triad pitches are their bread and butter. |

Permutate triads lots of ways; by playing one triad ascending then move up a fourth and descend with the next, or chromatic motion up or down. Add in the 2nd scale degree to create a major pentatonic flavor, to create Coltrane's choice over the 'Giant Steps' changes described just above, example to follow. Try running the seven diatonic triads through 12 keys. There's just tons of options with triads and various melodic filters. |

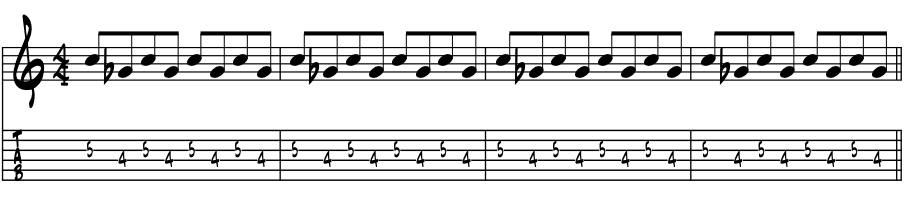

Triads are the super common, jazz it up, core launch pad for arpeggios, establishing their major / minor tonality and chord type. Most of our bass lines are triad based, especially in the blues. Spanning stylistically from rockin' Chuck Berry's classic bluesy essential, dig this core rock'n roll double stop blues hue'd of an idea to kick off "Johnny B. Goode." Example 5f. |

|

Got some sort of this coolness under your fingers yet? We each play it different, so there's a million versions to learn :) For once the blue hue arpeggio kicks it off, just hold on tight and don't stop. Tis an amazing thing what two very select pitches can do, especially through any version of the big roar. Just learn the lick here if need be, at some point we all will need it. Totally moveable, just great way to 'light things up' and kick one off, to set the house a rockin' and don't bother knockin', styled dance extravaganza. You get the idea :) |

In jazz, Clifford Browne's moody jazz 'Daahoud', both are triad / arpeggio based. Parker's 'Omnibook' and Coltrane's 'sheets of sound', totally totally chock full of blazing arpeggios. Ascending in their own days to become true innovative Kings of Americana Music. |

|

Evolving the triads into pentatonic groups. With the addition of a select pitch or two, we can quickly evolve our triads into the pentatonic group of five pitches. These are the 'no wrong notes' group? Yep. All butter :) Each pitch a keeper. Also, once the triad evolves towards pentatonic, for advanced readers here, we can skip ahead and add a big spoke to our improv wheel. |

This comes to us in the song "Giant Steps." Pioneered by John Coltrane, his improvised melody lines find a new sleekness for increased velocity, yet with the clarity of the triad / pentatonic combination of pitches. Coltrane solos through fast moving changes by using a root pitch based pentatonic scale for each chord. This not only created a sensation in its day, but opened up a whole new universe for using the pentatonic colors. Thus, another 'step' on our way to Parnassus. |

12 key cycle / major pentatonic idea. In this next idea, we simply outline the first four pitches of the pentatonic scale in quarter notes and move through an ascending cycle of fourths. This four pitch idea we can term our constant structure. We again take advantage of the properties of how the pitches lay on the instrument, to quickly scoot us through all 12 major keys with just a string, octave shift or two, all in a localized position. |

As a player evolves, moving a constant structure, whether melodic or harmonic, across strings or in parallel motion too, oftentimes becomes a thing to do. With that in mind, run this 12 key / pentatonic idea a couple of times, even as fun warm-up exercise, easily replicated and advanced with other aural colors and rhythms. Example 5g. |

A long term goal / anything from anywhere. What a lot of these last exercises are developing is the cognitive and physical ability to understand and create any of our musical elements from any pitch on the neck. A tall order for sure, with a lifetime's worth of shedding, and all that adventurous musical discovery along the way :) |

Author's note. With our intellectual arms completely around the resource, thanks to our silent architecture, we simply must each decide to what degree we need to understand the resource, then find those sounds on our guitars to bring forth the art within our hearts. And as we'll see as we move along in our studies, the musical styles we dig becomes a large factor in determining how deep we go in the theory. At least initially anyway, for there are no bounds for the curious n'est ce-pas? |

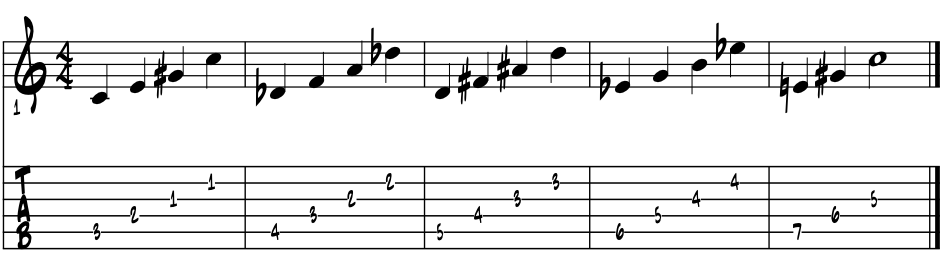

Notating the 12 pitches. In this next idea we simply move by ascending in perfect fourths. Starting from our open low E string we can use our guitar's standard concert tuning of perfect fourths before ascending to find our other pitches. There is an octave transposition in the third bar to keep us within easy range for most guitars. Example 5h. |

. |

E |

A |

D |

G |

C |

F |

Bb |

Eb |

Ab |

Db |

Gb |

B |

E |

. |

And yet again that perfect closure of the 12 pitches in its unbreakable loop. I'd imagine by this point in our process that the surprise factor of 'will this interval loop close' is probably long gone. Oh well, for what remains stays and has stayed for a couple of thousand years now, so we maybe aught to know it, or learn it by now :) |

For what is 'theory true' here in AK is the same 'theory true' southbound to B.C., Seattle, Portland, San Fran, L.A., westward to Austin, Nashville and N.Y. Across the pond to London? Paris and beyond? You bet. So is our own Americana music theory ever different? In one super colossal way yes. For we have pure weave of the blue notes, the blues and all its rubs to negotiate. |

Loops / tritone / #4 / b5 ... the halfway point to the bluest of the blue notes. Our last interval for this first 'loops' page we end up splitting the octave into two perfect halves creating the tritone interval, the b5 / augmented fourth / #4, the one time 'diabolus in musica', becomes the Americana clarion call to look here, see the injustice that can be sounded by the blues. Then, to embrace a new way forward for equality among sentient beings we're designed to be :) Examine the letter names, and basic intervals for our tritone essential, perfect midpoint of the perfect octave. ~ C Gb C ~ 'Tritone' really just means 'tri = 3, ... so three whole steps / tones in a row ~ C D E F# ~ |

While mostly shunned from much of the early and very limited literature we've inherited today, once the pitches are consistently equal tempered for creating harmonies, the tritone interval rockets to the top of the charts. For it energizes the traffic cop V7 chord, which also becomes our tried and true blues chord. The tritone helps energize and structure both the diminished and whole tone colors, thus the V7b9 and V7b5 chords, and all of their numerous substitution properties. The V7 chord, the tritone interval and colors ground a musical style, the blues, and is as potent a blue note we might ever find. From 'art shunned' to 'pure Americana essential', in just a half millennia or so. |

The tritone as a catalyst. V7 is of course the crucial chordal color of the blues. It's also the harmonic traffic cop directing our chord progressions, modulations and the original catalyst for chord substitution. Its interval closure is easy to prove, for the tritone splits the octave perfectly in half. Thus, two tritone interval leaps and we perfectly close our octave span. Thinking 'C' major here. 'C = C and Gb = F#' Example 6. |

Pretty tense sound eh? That's probably why it was shunned way back when. As we can see from the notation above in measure 1, the tritone interval splits the octave perfectly in half. All of our other pitches falling neatly in between the two segments. We can also clearly see to understand this idea of the mid-octave tritone, as represented on the lettered cycle of fifths. Draw a diameter line between 'C and Gb.' Example 6a. |

|

'C across to Gb.' Clearly the 'Gb' tritone lives directly across the circle from its tonic 'C' and there are five pitches either side. So if 'C and Gb' are directly across from one another and span a tritone interval, might that be the same for our other 10 pitches that are directly across from one another on the wheel ? Tis is indeed the case mon ami. We can select any pitch on the circle and locate its tritone by locating the pitch directly across from it on the circle. Handy ! |

A two pitch safety call. We can hear these two pitches and this important interval today from the emergency response vehicles siren as they carry compassionate people who thankfully come to the rescue of those in need. Example 6b. |

Tritone roots. In the Americana sounds, the tritone's original way into the music is probably as a blue note. And for us modernes, no easier way for guitarists to invoke the blues aura than sounding the tritone of the key we are playing in. Here is a quite common 'sounding of the tritone' to set up some further testimony. Thinking blues in 'A.' Example 6c. |

The gist of a tritone root pitch. Simply that if we play this sort of idea at any point in any tune, chances are the blues color and its aural magic is going to emerge. It's a sure bet to bring a blues hue to wherever we are in the music, and doubly so by simply repeating this call of a blue note, or repeating a phrase, like the one just above, over and over as a vamp, when taking a tune out etc. |

This ability to ground things in the blues, with just one key pitch, comes in handy as a super core Americana color for all styles and genres (handled tastefully). Come up with a lick that riffs too? Sounds better the more we repeat it ? Possible hook ? We'd better write it into a song then :) |

Tritone pitch as an accented passing tone in the line. In this next melodic idea, we find the tritone tucked into a rather notey melodic line. It gives a nice 'outside' pause to the swing, and creates a cool sense of suspension of time. This next idea is from one of mine, titled "Tuxy." |

In 'C' major, the tritone pause is at the close of the first measure tied over the barline. Do examine the full arrangement as time permits, as we use the same bit of the melody line to close out the arrangement. Ex. 6d. |

Just a jazzy styled line, suspensions in the melody are common in all of our styles. The double Two / Five of bars 3 and 4 adds to the verve and forward motion. |

Tritone in musical styles overview. So we won't find the tritone interval or its sound colors in folk music or children's songs, unless they're of a scary nature and even then it's rare, as the interval / pitches are hard to sing. Lasting children's songs are usually easy to sing. Also, in children's songs, so often just the dominant triad is used to nudge the cadential motion to tonic resolution. |

We surely find the tritone interval in every form of the dominant 7th chord, which is quite common in folk. We've all sorts of tritones in the blues and any blues / rock / country flavored mix. For the metalists, the tritone interval, sounded through their shredding gear, is really all through the literature, from the style's inception in the 70's on through to today's contributions. Help internalize the interval by singing. |

The tritone catalyst in jazz. Turns out that all of the tritones found in the above musics are generally also found in jazz. As V7 is the harmonic traffic cop directing our chord progressions, modulations and an original catalyst for chord substitution, jazz artists will often find that the tritone pitch, interval and pairing is a key that unlocks a treasure trove of theory possibilities. |

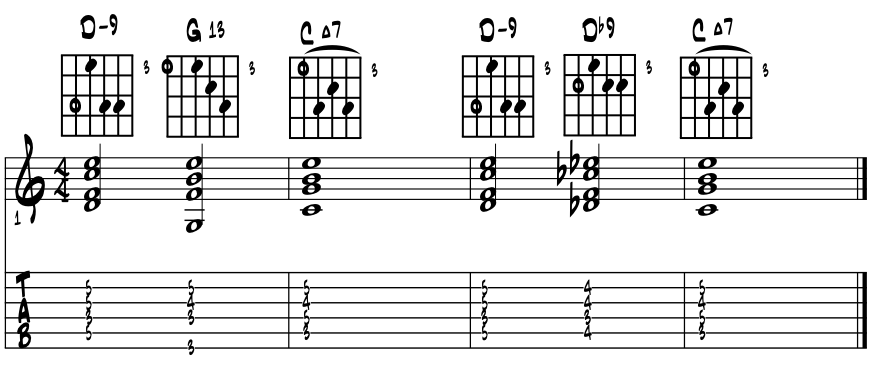

Tritone sub. Surely worth mentioning at every and any opportunity is the jazz harmony and cadential technique often termed the 'tritone sub.' Its theory creates a sleeker, thus faster, half step motion between the roots of the chords in play, while opening up other harmonic substitutions, thus generating additional melodic options. For as the harmony evolves, artists have expanded possibilities to play 'through the changes.' |

The 'tritone sub' simply directs us to substitute the written chord with a chord whose root pitch is a tritone interval away from the written pitch. With V7 chords, they hold in common the same two pitch tritone interval within. The next few jazz chords illuminate this above idea. The tritone interval between root pitches here is that the 'Db7 chord substitutes for G7.' Here's the evolution, thinking Two / Five / One in 'C' major. Ex. 6e. |

For some reading here, especially for jazz leaning artists, this 'tritone sub' idea is a paradigm shifter beyond measure. I know it was pour moi :) And these two harmonic motions are pure 'butter' for the jazz guitarist. |

While this process is mostly done with dominant type harmony as shown here, once we're comfortable with substitution theory and its practice, we'll end up using the concept and half step motion to also puzzle things around for the One and Two chord type harmonies also. |

And in a similar fashion to the diminished 7th chord's double paired tritone intervals, the basic V7 tritone sub can really energize and accelerate the sense of forward motion, tonal gravity and time (swing) in our music. |

The initial magic. The initial magic of what the tritone subs can do for us is easily seen in the bass line of the two sets of chords. Our 'D / G / C' becomes 'D / Db / C.' Those in the know will see the chromaticism of the tritone version. So just what is the big deal here? Well, like so many things in our ever modernizing world, sleeker tends to imply faster ... |

In the evolution of style and theory in Americana music, sleeker components not only allowed for brighter tempos but also the ability to slip new chords in between the existing progressions. These new chords can increase the improv challenge and encourage the inclusion of musical elements from, and to, additional key centers. |

So for those of us that blow 'through the changes', more options simply means more possibilities in creating their improv directions. More options also can mean a greater intellectual challenge of the music. Much of what happened in jazz between the late 1930's into the early 60's was facilitated by these 'sleeker elements' moving faster and faster and faster through musical time. |

So the more streamlined our motions are, the faster we can run them. The faster we run them, the more exciting they become. The more exciting they become, the more we might want to do it. Probably not all the time of course, but certainly sometimes :) |

A hidden agenda. So when the musical evolution of the dominant chord substitutions began to appear in the late 30's and into the 40's, the music gradually became faster, thus potentially more exciting. And a key aspect one might want to consider at this historical juncture is the question; haven't we historically made our music so folks would get up and dance? And when we dance to the music, what are we really doing? |

Halfway review. Since we are perfectly halfway through our discovery process of loops of pitches / intervals within the octave span, this would be a good place to split the discussion. Just makes for smaller pages so easier to load up out there in cyberspace. Next up, the interval of a perfect 5th and our continual search for perfect closure. |

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"You can't un-ring a bell." |

?

|

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |

Coda. Here's a few piano keys to help you sort out the pitches that become your melodies. |

|