|

~ perfect 5th through the octave ~

|

Nut ~ page 2 of 'loops of pitches.' Just picking up here where we left off there on page one of this discussion titled 'loops of pitches', so no new nutshell necessary. So, moving a half step up from the #4 / b5 tritone ... ? From the 'diablo 180' and onto to the second in perfection of sound, the perfect '5.' |

Loops / the perfect fifth / Five. So named 'perfect' for their bell like aural clarity, the sounding of the perfect fifth has often been the herald of great events in many of our histories, for as far back as we can go in our written and collective memories. |

Nearest to our octave center in both purity of sound and the maths of music, as we go on down this road it'll come as no wonder just how heavily we lean on this one pitch; 'the fifth' and interval of a perfect 5th, in all of our musics. For the perfect Five partners with One and the diatonic octave to direct our musical stories. |

For example, traveling sounding songs about movin' on sounding stories and tales are usually about going off to a 'somewhere' and then getting us back home. So as the story goes along, at some point we'll prolly sound the perfect fifth note ... and the sound of 'Five' in relation to One in a key center, initiates the aural and directional sense of musical energy, gets us heading home to One. ~ home is One ... then away to Five ... ... back home to One ~ |

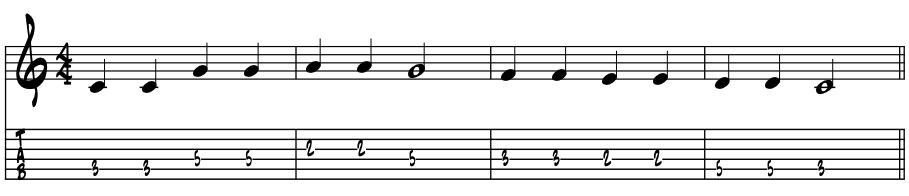

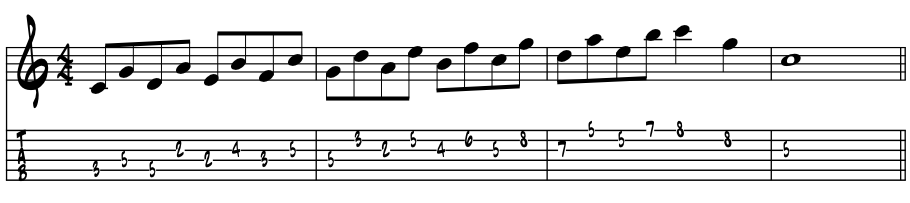

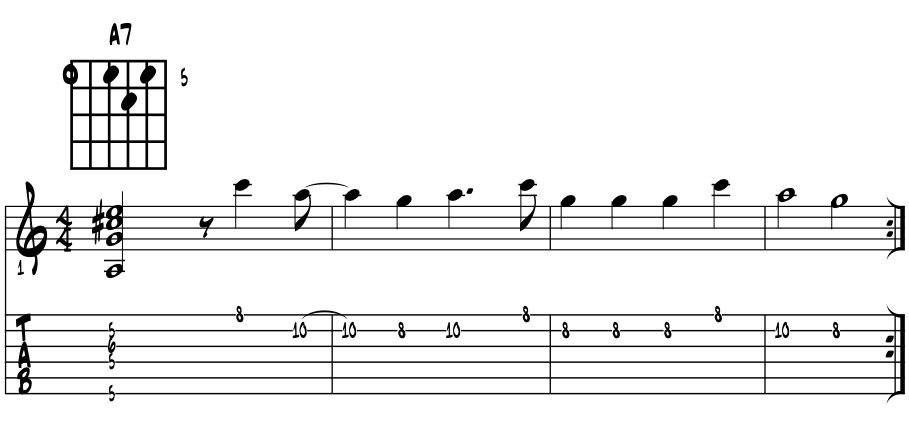

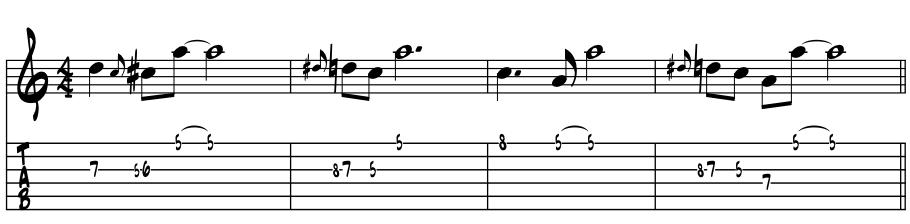

Reach for the stars. A most familiar melody built on the perfect 5th interval encourages us to reach out to the heavens above. It also could very well be one of the first melodies we ever learned growing up. I often segue into this one when out working, if the little peeps come up to the bandstand to say hi. So often to their great surprise and wonder, that they recognize the tune and can sing along with my playing. Sing this first measure of the perfect fifth interval pitches that represent the penultimate consonance of our musical intervals, from all the way back to antiquity to our modern day equal temper tuning. Example 1. |

|

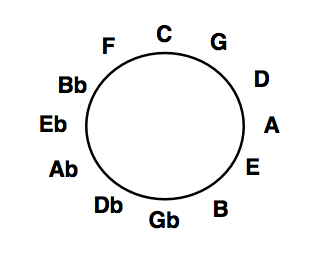

The cycle of fifths. A familiar melody to sound out? Those so inclined and fortified, consider running the last four bars through each of our 12 major key centers. Using the opening perfect fifth interval of the melody just above, we can move successively by perfect fifth's and create our cycle of 5th's. This visual arrangement of the 12 pitches of our musical system is one we'll see and use many times to organize our studies. Please examine the graphic and the music. Example 1a. |

|

|

A six and change octave span. As we locate our cycle of fifths pitches on the grand staff, the pairing of our treble and bass notation clefs together, we encompass the core 'six and change' pitch range, which we build into the seven octave span featured in the '88' keys of the piano keyboard. For guitar, this range translates to a very, very solid E to E three octaves for most acoustics, and beyond to a full fourth octave closure, with access of many electric guitars and a bend at the end. |

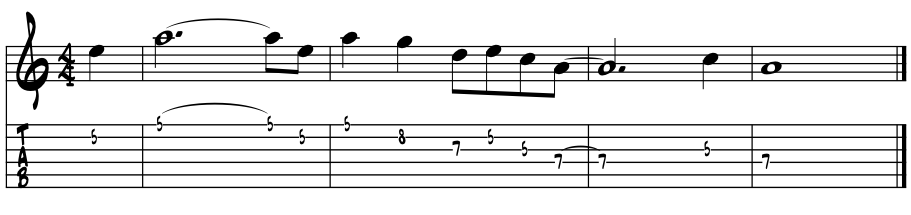

Loops / perfect 5th / minor / "Scarborough Fair." If all of our musical resources somehow seem even a bit more poignant in the minor tonality, the perfect fifth still remains the true traffic cop of directing our musical journeys. The power of the perfect 5th is epic in the minor key. Example 1b. |

|

Remember this melody? Note the perfect fifth leap in pitch into the second bar? As perfect a melodic cell as any ever written? That's the theorist in me talking. "Scarborough Fair" was a big pop hit for the folk duo Simon and Garfunkel back in the 60's, maybe time for another rendition ...? Oh, and cool with the 3/4 time? |

|

Loops / past halfway / inverting intervals. Now that we're past the halfway point in examining our intervals within an octave span, ( remembering that the tritone divides the octave perfectly in half ), we can add an interesting property to our intervals. In musical terms we say that each of our intervals can be inverted. |

By basically flipping them upside down, i.e., inverting, we find the same letter named pitch by moving in the opposite direction from our chosen starting point. We can measure the distances by simply counting the lines and spaces on the staff, or even using our fingers and toes to help count the pitches. |

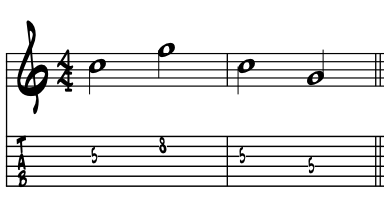

Up a perfect 5th = down a perfect 4th. For example, we can move from middle 'C up to G', which is a perfect fifth, or 'C down to G' which creates the interval span of a perfect fourth. Example 1c. |

|

Why we invert intervals. Inverting intervals helps us in a number of ways. It provides variety, helps in transposing from key to key, in shaping lines to fit registration for melodies, chords and different instruments as well as in generating new chord voicings. |

In addition, there is the theory side of inverting intervals, and that knowledge of the process might just shake something loose for you in your own creations. For we just never know where the next coolness is going to come from. |

Interval studies. Motivated players often include various intervals studies into their core training, to simply help get the resources they need completely under their fingers. Of course like many aspects of our musical development aside from theory knowledge, these are longer term shedding exercises that develop by necessity and morph on their own, as our own sound and style emerges. |

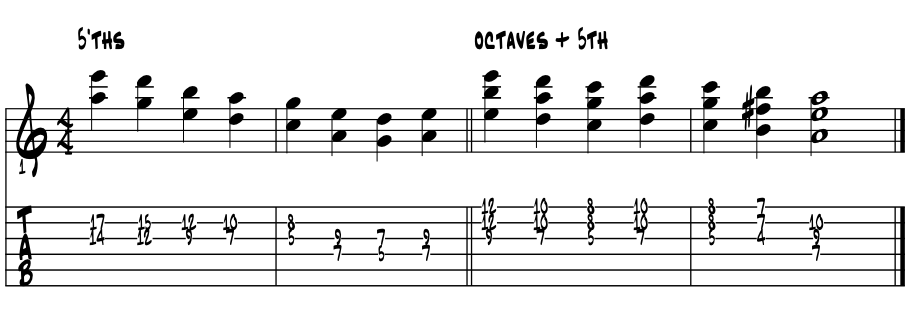

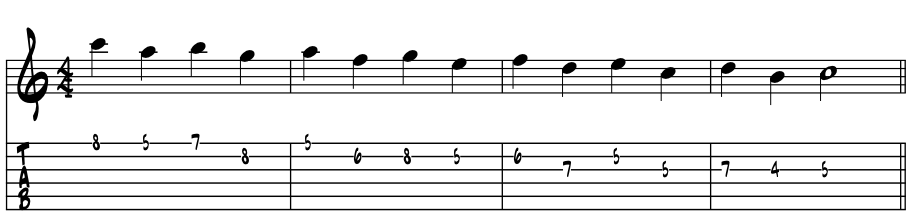

I'd imagine that anyone who wanted to tear it up with their single line playing would explore these ideas at some point. Folk artists might use these interval study ideas in training their voice. Especially in working on their vocal harmonizing chops. In this next idea, we use the interval of the perfect fifth, and diatonically filter it through the pitches of the Ionian mode / major scale. Example 1d. |

|

Essential challenges. The above exercise is not easy to play. If it is easy for Ya, speed up the tempo. For those so inclined, the interval studies become a sort of second tier depth in the preparation for the improvisatory nature of the Americana musical styles. For jazz players and other stylists so inclined, the interval studies are a joyous way to deeply learn the pitches on any instrument, scale shapes, intervals and arpeggios. We also gain a true sense of localized key centers, as we weave through the patterns. Through interval studies we can develop the chops to play the wider interval melodies of today's modernistas, and strengthen our own 'ears to hands' abilities. |

For at the historical core of the Americana sound is the timeless ways of human conversation we often term as 'call and response.' Further spiced up with the theme and variations idea, and improvising over, and or and through the changes / harmony, the interval studies are a true sort of calisthenics, that strengthen up our spontaneous abilities to negotiate the improvisational nature of composing our music in real time. |

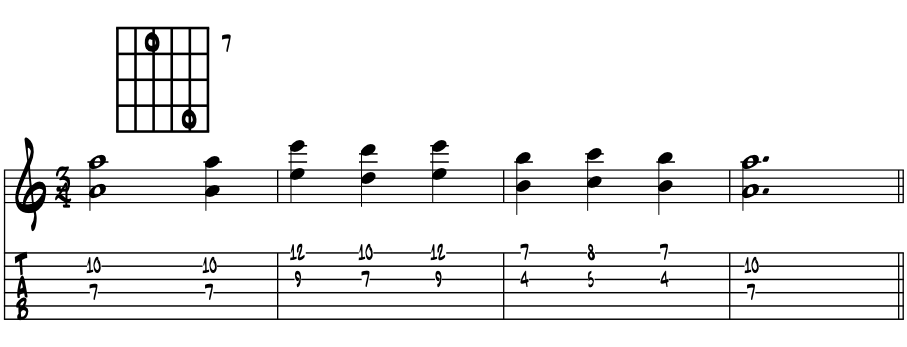

Root / fifth melodies. The idea of combining the perfect fifth with melody notes is not all too common, but it is in the literature and can be a very powerful sound. Blues rocker Duane Allman does this a bit as does jazz man George Benson, who sometimes adds a fifth between his octaves to turn up the heat a wee bit more. Example 1e. |

|

Root / fifth chords. As the overdrive and sustain gear evolved in the 80's and forward, the number of pitches in the power chords were reduced to ease up on the amount of pitch processing, creating cleaner distortions. Root and 5th is the staple for all kinds of coolness. |

Perhaps needless to say these days, that these two note chords, run through a pedal or two and stack, can create a real roar. Their sleekness encourages quickness, both up and down and across the strings directions. |

Loops / the minor 6th. The minor sixth interval loop closes upon itself in three quick leaps. As an integral part of the minor tonality, the minor sixth provides a poignant and somber touch to minor tonal environment. A crucial component of the minor Four triad, this interval also creates a nice suspension, typically resolving by moving downward to the 5th of our tonic key, so b6 to 5. |

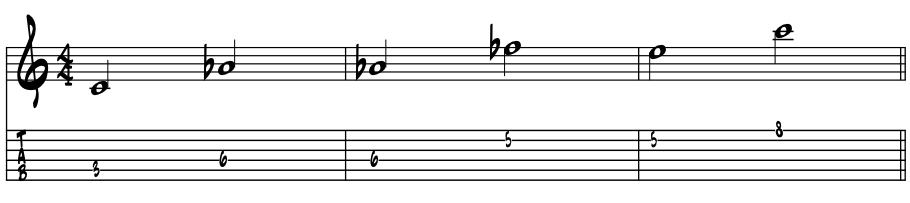

Here are the three leaps of the minor 6th interval to span the octave. Do note the enharmonic spelling between the pitches of the second and third measures below. That 'Fb' and 'E' natural are termed enharmonic equivalents. Example 2. |

|

One powerful interval. The emotional character of the following melodic idea is in a large part based on the interval between our tonic root pitch and the minor 6th. Even without the harmony or bass line for support, the artistic and emotional intent of the line kinda just jumps right out. Like the minor 3rd, give the minor 6th a bit of a push, add some vibrato, to bring forth the color. Here's one of my own melodies, normally in more of a samba 2 feel, I wrote it for a dear friend Skye, who was having a blue kind of day. Here presented with a bit more poignancy as in a ballad. Example 2a. |

|

The minor 6th / the leading tone and natural 9. Theoretically, this last line combines some interesting elements. As our combined minor tonality is comprised with a wide variation of pitch combinations; the natural, harmonic and the melodic minor groups of pitches, recall that its crucial core remains centered between our root pitch and the minor 3rd above it. These two pitches set the tone to minor. And like most things in the Americana fabric of sounds, everything else is fairly negotiable. So in the above melodic line, by including the minor 6th, the leading tone and natural nine all together, our overall parent scale for this section of the song leans to the harmonic minor grouping of pitches. At least in theory :) |

In the bridge. In this next melody idea from a different song of mine, the minor 6th interval opens up in the bridge section of the composition. As the 'A' section pitches stay within a perfect fifth, the sounding of this minor 6th is also quite effective in bringing a poignant longing to the senses. Ex. 2b. |

|

|

Feel the pull of the minor 6th interval? Really gives this bit of a melodic sequence a nice apex to descend from. |

This last melody is based on just a 'wisp' of a motif that I learned from a friend here in Alaska years ago now. She grew up on the Yukon River in Ruby, Alaska and her grandmother would sing a similar song to her. |

Loops / inverting intervals / magical number '9.' Not sure why this works the way it does but ... each of our intervals within the octave span, when identified by number, when added to their proper inverse, combines to equal nine. Examine the following chart. Example 2c. |

interval motion up |

interval motion down |

9 |

minor 2nd |

major 7th |

2 + 7 = 9 |

major 2nd |

minor 7th |

2 + 7 = 9 |

minor 3rd |

major 6th |

3 + 6 = 9 |

major 3rd |

minor 6th |

3 + 6 = 9 |

perfect 4th |

perfect 5th |

4 + 5 = 9 |

augmented 4th |

diminished 5th |

4 + 5 = 9 |

perfect 5th |

perfect 4th |

5 + 4 = 9 |

augmented 5th |

diminished 4th |

5 + 4 = 9 |

minor 6th |

major 3rd |

6 + 3 = 9 |

major 6th |

minor 3rd |

6 + 3 = 9 |

minor 7th |

major 2nd |

7 + 2 = 9 |

major 7th |

minor 2nd |

7 + 2 = 9 |

Crazy huh? We only mention it here in so much as it is a cool discovery for sure. Also, that as a self check, when calculating music and math numbers, we'll find this kind of perfect closure of numerical magic happening in lots of cool ways. This is just one of many. Here is the musical sound of the above chart. Example 2d. |

|

Not much music here is there? What we do get from this idea is a comparative sense of the consonance and dissonance quality of these intervals, how major inverts to minor and perfect stays perfect, all within the perfect octave span. |

Close the major 6th loop. So if we invert the major 6th to the minor 3rd, and we know from a previous study that the minor 3rd closes its loop in four leaps, then surely our major 6th interval should do the same yes? Please examine the music. Example 3. |

|

Yep, four leaps to close. Cool. So the inverse intervals match up with perfect closure, and the universe is in order yet again. These closed cycles of pitches can create formats for composition, a framework that we composers can use as an architecture for songs. And while they potentially can become too predictable, we can artistically alter things in unpredictable ways to suit our muse. For as we puzzle our ideas together, shaping their emotional dynamic within the tonal gravity and the aural predictability of each style, we use these sorts of cycles of pitches as architectures to build upon. |

|

Leap of the major 6th. A joyous leap like no other in the American sounds, the major sixth holds a cherished position of our intervals. Jumping into the way back machine, this next melody goes all the way back indeed into the Americana book of popular song. Its jaunty air is in good measure created by the major 6th interval, which among other qualities, is a core pitch within the major pentatonic color. Example 3a. |

|

Remember this line? "Shortnin' Bread" is the kind of melody that can go right to the core of American swing. I firmly believe that this and similar melodies, being part of the public school music / band curriculums since the 1900's, are surely the melodies that so many of our musical heroes played as kids in school. Further, that from these melody lines, the magic of our rhythmic swing, of Americana music has evolved. |

|

Author's note. I've added in the major pentatonic scale shape in the last idea for folks new to guitar. This one shape can yield a lot of good melodic jamming. If necessary, start off by getting it under your fingers and finding the pitches and melody of "Shortnin' Bread." Then work at the rhythm, capturing the joyfulness in the line, as generated from the major pentatonic color. |

And through 12 keys. Again the idea that this melody can be equally projected from each of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. So for those so inclined, do shed this melody, by ear, through all 12 major keys, and then maybe look to quote it in your next solo :) |

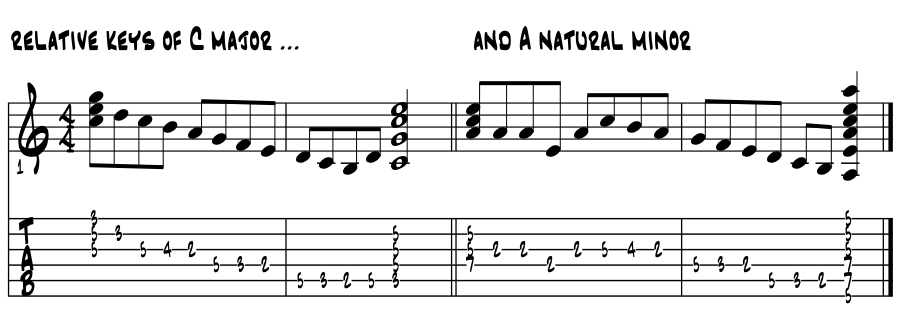

Loops / major 6th /and home of the relative minor. We can also locate the relative minor scale from the major sixth degree of the major pentatonic and major diatonic scales. There's just a natural warmth, balance and power to how the major 6th sits in the major tonality, that hints to more to explore from this point in the loop. And sure enough, we find the Yin-Yang portal pitch to the minor tonal kingdom :) |

So while the intervals and scale formulas, in creating the two unique groups must shift, their letter name pitches, remain just the same. Ah, so the now ancient looping modal magic of it all? Indeed :) Examine the following chart of the exact same letter name pitches, pairing up our relative major / minor groups of pitches. Ex. 3b. |

scale degrees |

root / 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major scale |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

A minor scale |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

|

Cool huh? Here the difference between the major and minor ? Surely a giant first step into hearing and understanding all things Americana musics :) |

In composition. This pairing of the 'relatives' is very common in composing music. For it cores the essential chordal 'diatonic 3 and 3', a description of the six triads that support a million songs. 3 major triads + 3 minor triads = 6 diatonic triads There are classic songs penned in every style that pair these two, now ancient colors. From the 1930's, all "Summertime" probably tops the Americana list. Into the wayback and across the pond to source the also essential spawners, and now timeless, "Greensleeves" and "Scarborough Fair." Learn these three songs, in a key or two, and super expand to understand and fully utilize the '3 and 3' ... and then some :) |

|

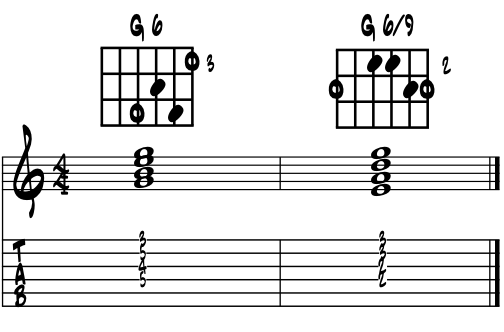

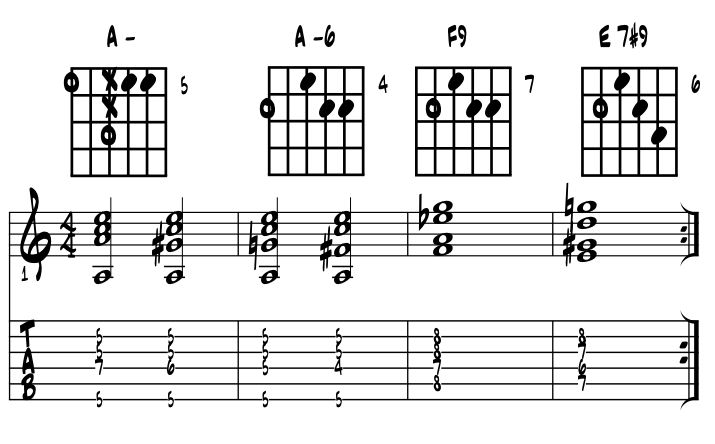

Loops / major 6th chords. This interval also lends itself well to coloring both our major and minor triads. We often find the major 6th chord in the 'jump' blues and jazz styles. Tight and bright on the left, and some Hollywood on the right. Leave the bass note off the 6/9 and both of these shapes pop along real nice. Ex. 3c. |

|

These relatively friendly chord shapes come in handy with their ability to move latterly up and down the neck. Termed plane-ing or parallel motion, they easily add rhythmic overdrive to the motor. Try using the half step lead in motions with these two shapes, as they're especially potent in making things swing. Rockabilly leaning cats of all stripes take note. |

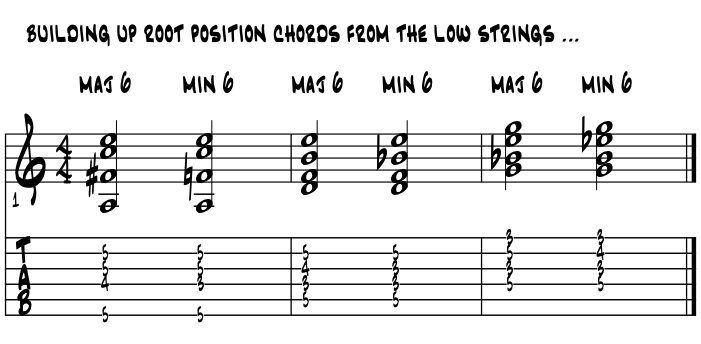

Loops / minor 6th chords. In this next idea we alternate major 6th then minor 6th, as built within a minor triad. Examine the colors, here out of context they sound ... 'unique :)' So either 6th, major or minor as measured from our root pitch, is theory groovy. Here's a few comparative shapes. Example 3d. |

|

Sound ok? 'Minor 6' chords are sort of rare. Watch melody notes, key signature, the root pitch of the chord, thinking diatonically in a song, for added clues as to which '6th' to sound in a song. 'Go diatonic and think from the root.' For it's either just one or the other :) And with the addition of a 7th to our triad, '6' moves on up an octave to '13' n'est-ce pas? And now we've some space to ponder. Plus, lest we forget ... the passing 7th. |

A tricky spot. The 'A'-6 voicing from the idea just above is a pretty neat chord. Of course it's an 'A'-6 chord but its pitches can also create a second inversion dominant 'D'9, and when rooted on 'A', it becomes a first inversion, half diminished 'F#'-7b5 chord or then 'D'9 / 'A.' All of which are diatonic to G major, examine the pitches. Ex. 4. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

G arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

A min 6 |

A |

C |

E |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

. |

F# -7b5 |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

. |

. |

. |

. |

D 9 / A |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Does this mean we can sub out for the these chords with one another? Yes, pretty much, depending on the style, the instruments involved and direction of the music. We 'sub out' to create variety in improvisation, or to find a better 'fit' for a chordal piece in a puzzle in supporting a melody. Lots of cool reasons really. |

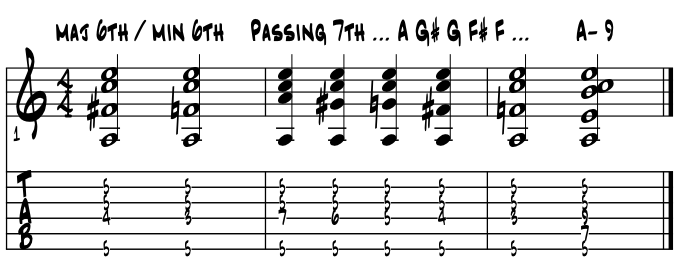

The spot. Thinking that the written key signature of a lead sheet applies to only (?) to the melody line, in most cases, if a cat see's 'A-6' written, chances are they'll sound the major 6th above the root, as say if the chord is used in the above 'passing 7th' motion. Yet, thinking 'A' natural minor, paired with its relative key 'C' major, this can become an 'F' in the chord, so we diatonically generate a minor 6th interval above the root pitch, so an 'A' -6 chord also. So by knowing what key we're in, and using its diatonic pitches to build chords, we have a way to sort this out. Today, the passing 7th is cliche, so there's that tradition for major 6th over a minor triad. This 'major 6th' shades things towards the Dorian color. Minor triad / minor 6th? Pure Aeolian magic. Compare the two thinking from the root pitch 'A.' Example 4a. |

whole step 5 to 6 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

||||

root |

-3 |

5 |

maj 6 |

root |

-3 |

5 |

min 6 |

|

A |

C |

E |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

F |

|

. |

. |

whole step 5 to 6 |

. |

. |

half step 5 to 6 |

|||

|

So what? So just what is this in terms of the theory? Surely the 'F#' is a lean towards 'G' major. It's also a lean towards A melodic minor. If we voice the chords as in the above manner, we place the 5th, 'E' above either 6th, 'F or F#.' These are both fairly common chord shapes. Quick review. In the above passing 7th idea, we pass by the 7's through the major 6th to minor 6th, often a penultimate resting point before the final hold. |

|

So again we see the chromatic motion tastefully handled. All of this is not uncommon when exploring the minor tonality, just 'pushing past the basic boundaries' a bit of what is diatonically available, By finding the pitches in between the diatonic seven points, we expand our resources to express the 'art in our hearts.' |

Loops / the minor 7th. Melodically, the minor seventh interval or blue seventh, historically plays a rather crucial role in creating the Americana sounds. Also commonly known as 'flat seven', its proximity to the tonic creates an essential suspension for infusing a blues color into the music. Minor '7' is also a part of the Mixolydian formula, that essential grouping for bringing forth mucho mucho Americana in the folk, bluegrass, newgrass, fiddle tunes, country and beyond stylings. |

Harmonically in a V7 chord, the minor 7th interval is one half of the two note, tritone catalyst (a combined major 3rd and minor 7th above the root ) of the dominant seventh chord. This pairing creates the dominant V7 chord type, which provides the aural tension to direct the flow and direction of the music. |

We often create cool and danceable vamp ideas with the blue 7th, most often from tonic One, down a whole step or two frets, to b7. We find these vamps in many of the Americana styles of music and dance. And of course, the minor 7th is a must have in creating the natural minor tonal environment and associated modes. So like its inverse the major 2nd whole step, it'll probably take 6 leaps to close the loop. Here is the music for searching for the perfect closure with the b7 interval. Example 5. |

|

Bingo, six leaps it is ... I love this theory! |

Flat 7 in action. In this next idea is a total 'The Doors' inspired chant, whereby we're simply encapsulating the tonic with the blue notes b3 and b7. Generally an easy lick that gets good mileage. Learn it here if need be. Example 5a. |

|

|

Shake these pitches and give them some wobble, to bluesify as they say. The major 3rd, C# in the chord, and the blue 3rd, C natural in the line, making for some of the blues rub spice of the Americana sounds. Both are clear out of tune with The Mother, so rub them some extra to bring their true blue :) |

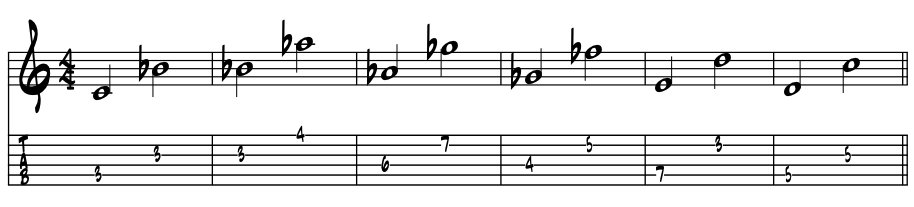

Loops / the major 7th / leading tone / Seven. If like its inverse interval, the minor 2nd or half step interval, the major 7th interval will need all 12 occurrences to close back upon its starting point. So we'll need all of our pitches? Yep, all 12. Based on the octave transposition technique, this next lick creates an interesting feel, a descending chromatically enhanced, noire character of line, a mood which somehow vanishes with the sounding of the major seventh chord to close the idea. Example 6. |

|

That's a lot of dots yes. But these sorts of fingering patters can be fun, challenging to play and get us to places artistically we might not venture to. So we are exploring, knowing that good ideas for a 'next work' can come from anywhere. These sorts of parts are what artists might call 'worked out.' And as such become puzzle pieces that can be anywhere. |

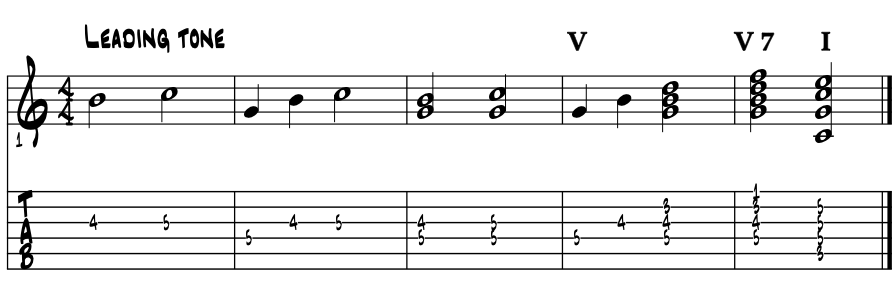

As the leading tone. As this theory name implies, the interval of the major 7th above our root becomes the strongest of our pitches in terms of our tonal gravity. Proximity to the tonic by half step interval seals the deal for the leading tone 7th. So named by its ability to lend an often urgent and poignant direction to the music, artists use this pitch to shape the tension / release dynamic within their work. Located a half step below the tonic, its natural, organic inclination is to resolve tension by moving upwards by half step to our tonic pitch, which designates the key center of our song. |

This next idea is more of an interval study of descending 3rd's than a melody really, but it does eventually get after the resolving qualities of the leading tone. In 'C' major, our penultimate pitch is our leading tone 'B' natural, which resolves up by half step to bring this phrase and motion to a resting point. Example 6a. |

|

Sense the direction? Sense the direction in the line and its impending resolution? Cool. That's what the leading tone is all about. Of course, the repetitive motion of the interval idea or cell, lends to the predictable outcome, but the leading tone resolution by half seals it all. |

It is this sense of predictability, to hear where music is going, that helps to shape the musical art we create. Understanding the basics of our music theory is a way into developing an understanding of the various degrees of predictability and resolution. |

Just how predictable. While this may sound like a way big ol' can of worms, and it potentially is, the basic idea here is that regardless of musical style, as artists we balance the tension and release of the music we create. Whether instrumental or voice and storytelling, our art shapes this tension and release through our stories. Often termed a 'plot or story arc', in plays and scripts etc., knowing what is next in the story / drama gives us a vision to craft the music to aurally capture the energy of each moment, and knit all these together into a score. And while there are many musical ways to create this tension and release, and to create expectations and surprises in the music, in tonic centered music, the leading tone is one powerful tension / release creator. |

|

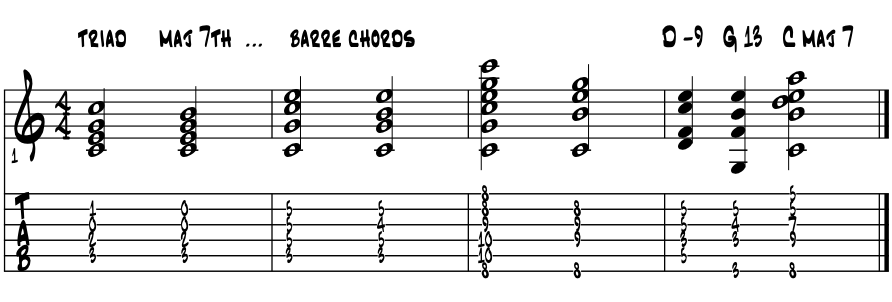

Leading tone in harmonies / tonic One chords. Jazz and pop players build this major 7th pitch into their harmonies, creating a lovely softened, yet still passionately directed tonic color for supporting their melodies. We'll hear this color all through our Americana styles today, as its an easy way to jazz up any song in any style. In this next idea, we 'soften' major triad voicings into major 7th shapes. Please examine the pitches in 'C' major. Example 6b. |

|

That last chord is a 'major 7th?' Yep, sure is. We've the root to major 7th interval in the two lowest pitches. So must be. A Hollywood chord? Probably that too :) |

Leading tone in V / V7. In a major key center, the leading tone pitch is right plum smack dab in the middle of the diatonic major triad we build on Five. It'll pair with Seven, to create the essential, two pitch tritone pairing within V7 that makes the tension we resolve in the 'V to I' / Five to One cadential motions. Please examine these letter pitches and their aural magics, thinking in 'C' major. Example 6c. |

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

G |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

C arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

G |

G triad |

. |

. |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

G 7 |

. |

. |

G |

B |

D |

F |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

Cool and easy enough huh ? Major Seven just loves to resolve right on up to Eight. Minor seven too, but then we're usually bring some blues along too :) |

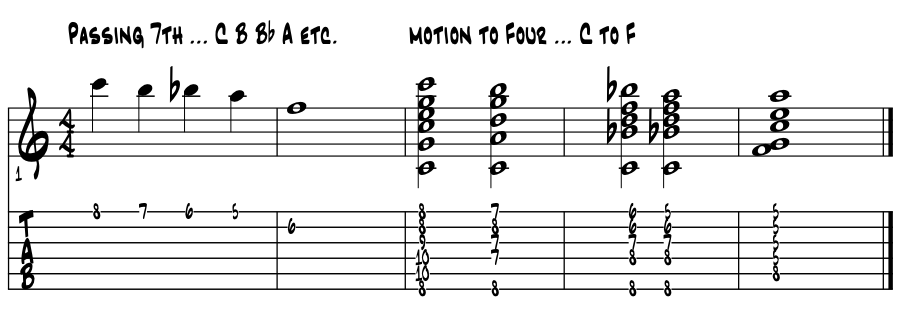

Passing 7th's. In both the major and minor key centers there's a solid pitch motion often called a 'passing 7' idea. Usually created from the tonic pitch, down chromatically so by half steps to Six, nicely color toning up our tonic triad along the way. So chromatic? Yep, chromatic. motion by 1/2 step = chromatic And in the 'what goes up must come down tradition', it'll work in reverse. It's just not as common. One consistent exception to this 'reverse idea ?' In the blues, the core bass lines, where either ascending or descending lines direct and clearly outline the motions. |

In a major key. Easy in theory, yet super powerful emotionally, timing this lick can be tricky at first, as this 'passing 7th' bass line often directs us right on over to Four. Example 6c. |

|

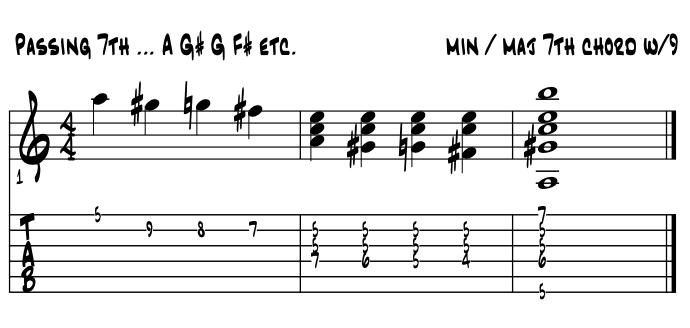

More common in a minor key? This 'passing 7th' could very well be more common in minor. Same basic idea really, just backed this time by the minor triad. Along the way we we pick up the 'minor / major 7th combo chord color. Handy for us guitarists that get to back up poets, they ALL love this chord :) Makes their thing ultra ultra groovy. Another Hollywood chord? Probably. Regardless, passing 7th thinking in 'A' minor. Ex. 6d. |

|

Blues and pop composer and pianist, Leon Russell's lovely pop ballad "This Masquerade", a top 40 Grammy winning super gem, features this 'passing 7th' line in the front four measures of its eight bar A sections. Here, a similar passing 7th again in A minor. 'X' marks the spots. Example 6e. |

|

|

Nice sound yes? Have heard it before? Cool. No? Oh then yet another first :) Learn it now? Work it over a few times and you'll have it. Even singing along with this playback example a couple of times, will lock some of it in for later. Also, explore to change fret position to find this line in other spots on the neck for key centers etc, i.e., search other string sets for the same sorts of colors. |

Octave / our one leap wonder. One octave leap is all it takes to gain that perfect theoretical closure we seek. With its 2:1 ratio, and an aural purity unmatched by any of our other intervals, the paired octave pitches become two focus points, two book ends, the two poles between all of our 12 pitches. Remember this old time melody? Example 7. |

|

What a line! Play ball! Music to set the era and a scene we all might enjoy ! The octave leap starts off the magic. |

Other classic melodies that initiate with an octave leap? Harold Arlen's "Over The Rainbow" and Mel Torme's "Christmas Song", are two beautifully crafted Americana classics, whose melodies initiate with the octave leap. Of course, we can find this interval in the middle of the melody line also, anywhere really. The now age old classic from across the pond, "House Of The Rising Sun" is one such melody, with a show stopping, descending octave interval to start its second phrase. |

Whomping on the tonic. Changing gears a bit here, but while we're talking octaves, these next ideas are ones that blues artists love, and come to think of it, so many blues licks often end up with the upper octave pitch to complete the idea. The reverse of this, a descending line, might even be more the case through the literature, a top to bottom running of the blue notes within a key center. |

Here are four, one measure blues ideas, that close to the tonic pitch. And that whomping on the tonic thing? Oh, just a reminder that when all else fails, while 'bringing it', we can whomp that tonic pitch / octaves, in the blues and beyond, and drive it all right into the barn and close the doors for the night. Example 7a. |

|

Find any coolness? I think the second idea is my current tops. These ideas are all from the one core, movable scale shape that, in 'A' blues, lives at the 5th fret. There's more blues ideas at the other end of these two clicks. |

Blues mojo. I'm not exactly sure if this is the right way to use this term but we'll see. In every blues player's development, there comes a point where they discover and can create a phrase unaccompanied, often four bars, that absolutely locks on the blues groove of their own locally created universe. Any time, any key and any weather etc., they can play this lick and set the blues mood a happening, our own blues mojo lick. |

Once we own one, we'd all might say they have a bit of the blues mojo. So often this mojo lick is also bookended by the octave interval pitches. Thus the case in the following line "The Truth Is ... Ya Just Don't Love Me No More" Composed by Jacmuse. Example 7b. |

|

Three's a charm. This last blues mojo four bar phrase is also a core idea that can be repeated three times and create a blues tune. Simple as that? Yep, simple as that. We also call this lick the hook, that essential bit of spark and magic that brings our true life experiences to a musical life in a song. Just match up the words of the title with the pitches, and our mojo lick song is born. Tell me, tell me please ... what's not to love?' |

Loops / octave doubling. Another fairly common sound with the octaves is to play the melody notes, written or improvised, with what is commonly termed an octave doubling technique. Jazz guitar legend Wes Montgomery was the king of this sound in his day. Mr. Montgomery's sense and depth of swing was new in its day, and really got everyone's attention. In both his octave melodies and improvisations, there's his super clear artistic signature in melodies and rhythms. Once you hear it, you'll always recognize it whenever or wherever you hear it. |

|

Southern rock pioneer Duane Allman also built melodies and solos with the double pitches of an octave interval. And surely Allman heard Wes Montgomery. Allman oftentimes would rapidly 'fan' the octave doubling, probably with a pick, casting a modal spell with the natural minor pitches and the blue notes he so dearly loves and knows. Then the slide, and even more howling. Now true blue pitched notes are 'felt' and ensconced within the octave range. "At Fillmore East" is the remarkable capture of all the band's magics together. |

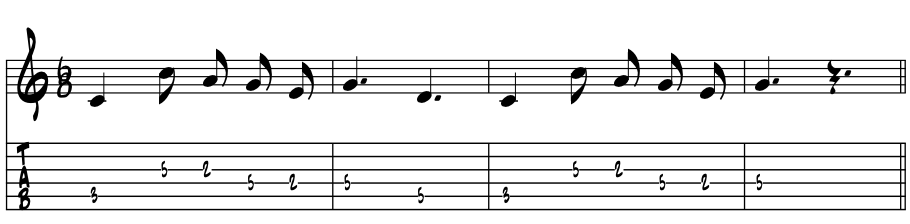

|

Nowadays, most jazz players find a way to work in this very cool octave doubling sound somewhere in their music. Here, try this first phrase of "Scarborough Fair" in octaves. In 'A' minor, Example 7b. |

|

Ok with sounding the octaves? It's tricky for sure. We generally mute the pitches in between. Try the thumb sweeping across, maybe thumb paired with index to pluck together, or thumb, index, thumb, creating a three note riff that can make for a nice triplet figure. And combined with regular picks, there's all sorts of ways to sound the octaves. Keep on going and you'll find your own way that's best. For playing music, and how we each do it, becomes very natural to us once we connect up our dots ... heart, head and hands and shed :) |

So a perfect four bars ? Timeless melody huh ? Ancient nowadays really. "Scarborough Fair" went to # 11 in the mid 60's. It's surety of musical form provides a lot of room for showcasing an artist's ideas through the minor, Dorian minor moods. A good melody to rote memorize and everyone in the room should know it. It's been around long enough now that if ya don't know it, yet, just learn it here and we've together yet 'another first.' |

|

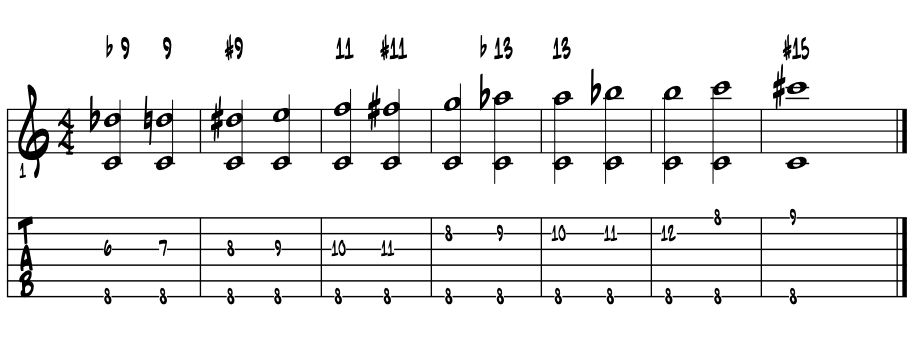

Beyond the octave. Moving past the octave interval and into the next span of pitches, we simply start back at the beginning just as the first time, with a half step interval. Our '1 - 8' diatonic numerical labels now become '9 through 15.' So, b9, 9, #9, 10 etc. And while we do hear these wider intervals, as measured from our root pitch, in improvised melodies, they're rare. The major 10th is a common keyboard voicing strategy. So mostly for advanced jazz artists mostly, though some singers will take the leap too :) Termed generally the 'wide interval studies', when successfully sounded in their musics they create some wonderful sorts of energies and spaces in the improvisational environments. Are these similar to skipping pitches in the arpeggios ? Yes and no :) |

|

While melodically these wider intervals are somewhat rare, we surely do find these 'beyond the octave' spans in the harmony. We guitarists refer to the arrangement of the pitches in our chords as its 'voicing.' Pitches beyond the octave generally become the chord color tones, the upper extensions or even just known as 'tensions', in some circles of thinkers. |

Octave + intervals. Here is the written music showing our upper pitches moving into the second octave above the root pitch 'C.' To avoid confusion, and to stick with what we see in common practice, included are the numerical names for the intervals we use everyday. These numerical designations are placed above their corresponding notation. |

In common practice, the intervals unnamed in the following graphic do not get any special designation, as they simply retain their lower octave labeling. Also, look to the written chart which follows for quick explanations of each of the intervals and links for discovery. Ex. 8. |

|

Intervals beyond the octave. |

||

b9 |

a rather common jazzy dominant chord color, as V7b9. | |

9 |

commonly used in all three chord types and the bossa, pop, blues and jazz stylings, a very handy color to deepen the passion of the moment, the dominant 9th chord, V9, is THE core funk chord of the 80's or so, also a strong basis for adding additional colors or altering the 9 to its half step neighbors, b9 or #9, minor 9, ii-9, is dark and passionate, tonic major 9, I maj 9, is stable, warm and ready to go and solid to return to, bossa nova loves the 9th. | |

#9 |

exclusively a dominant chord color tone, very common in blues and jazz, V7#9. | |

minor 10th |

simply our minor 3rd moved up one octave, a wider interval oftentimes used in the left hand of piano voicings. | |

major 10th |

simply a major 3rd up an octave, important in chord voicings, especially in the left hand of piano bigger chords on guitar, also used like an octave doubling but with the major 3rd's, our lines and sequences 'in 3rd's, as with the arpeggios etc. | |

11th |

essentially a perfect 4th now up an octave, but a common designation in suspended chord harmony, especially on Two and Five chord types. | |

#11 |

essentially a flatted 5th up an octave, designated as #11 if there is a normal 5th in the chord also, generally implies a whole tone quality, and even some polytonality. | |

p 12th |

simply a perfect 5th up one octave, with no special designation. | |

b13 |

essentially an augmented 5th in blues and pop chords but often seen as b13 in jazz chords if the voicing also has a p.5th below. | |

13th |

simply a major 6th up an octave, a rather cool dominant chord in blues and jazz with easy chord shapes to create the coolness. | |

b14 / b7 |

simply a minor or blue 7th with no special designation, up one full octave. | |

14 / maj 7th |

simply a major 7th with no special designation, up an octave. | |

15 |

our tonic pitch, up 2 octaves, with no special designation. | |

#15 |

comprised of two octaves and a minor 2nd, very uncommon and a real trainwrecker overall, but it is the correct sounding pitch of a purely built and sequenced, ascending major 3rd / minor 3rd arpeggio, and can be a hauntingly beautiful, true one of a kind chord when appropriately placed, also the portal, and basis of a newer, more modern system of composition and improvisation, based on a two octave arpeggio that weaves the ancient Dorian and Lydian colors. | |

Review, that's all for this chapter folks. Got a sense of this perfectly closed loops of pitches' concept ? We didn't find any ways, not one, to get outside or break its loop yet? Even #15 is has its perfect closure. It takes two complete arpeggios, 1 to #15 twice, to close ... after four octave ascending. '88 keys on a piano' ... got plenty :) It is a fairly simple idea this 'looping', but 'perfect closure of' and 'loop of pitches' illuminates the entire resource in a kind of flash, knowing other pieces of the puzzle will come along as the art is revealed. |

Larger loops? And what happens when we combine two or more different intervals in creating our loops? While you probably already know what is going to happen, might this be a basis of new compositional schemes for our pitches ? Closed loops of a sequential and symmetrical pattern ? Hmm ... |

So what's next? The relative loops of major and minor. To understand their theory basics. For easy 9 of 10 Americana songs music are written with an overall major or minor key color scheme, and of course the weaving of these two tonalities together. Now that we know that any way we slice and dice our pitches, that our loops will always hold together and close back to their starting point, we just need to place them into a musical setting and animate the pitches into life through time. The 'Yin ~ Yang' balance of earthly karma can be represented aurally in our major ~ minor pairing. Its aural palette of colors painting the stories of our lives day to day. Here's a chart of the letter names pitches for the relatives (share the same pitches), of 'G' major and 'E' minor. The 'naturals.' Example 8. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

G arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

triads |

G B D |

A C E |

B D F# |

C E G |

D F# A |

E G B |

F# A C |

G B D |

chord quality and diatonic # |

I |

ii |

iii |

IV |

V |

vi |

vii |

VIII |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 ~ 8 |

a one octave span |

|||||||

scale degrees |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

1 ~ 15 |

a two octave span |

|||||||

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

E- arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

triads |

E G B |

F# A C |

G B D |

A C E |

B D F# |

C E G |

D F# A |

E G B |

chord quality |

i |

ii |

III |

iv |

v |

VI |

VII |

viii |

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"You have to both understand the box and be able to think outside it." |

wiki ~ Paul Krugman

|

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |

Coda. Here's a few piano keys to help you sort out the pitches that become your melodies. |

|