|

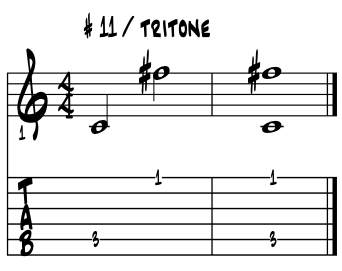

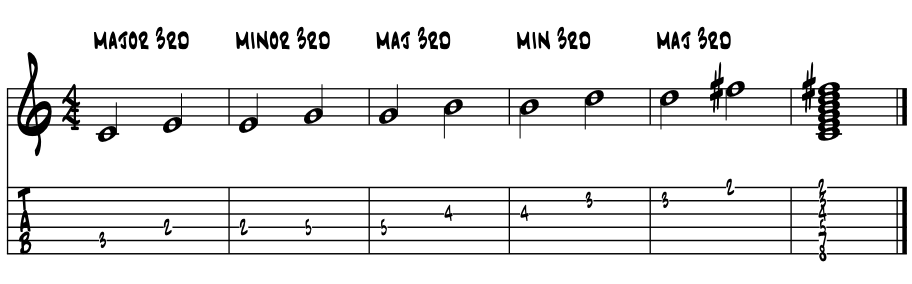

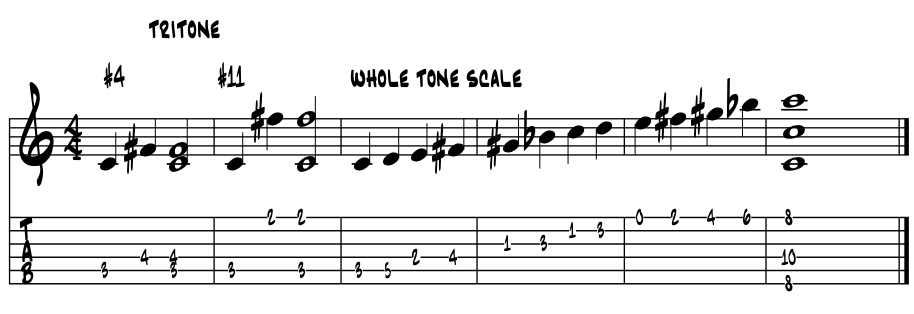

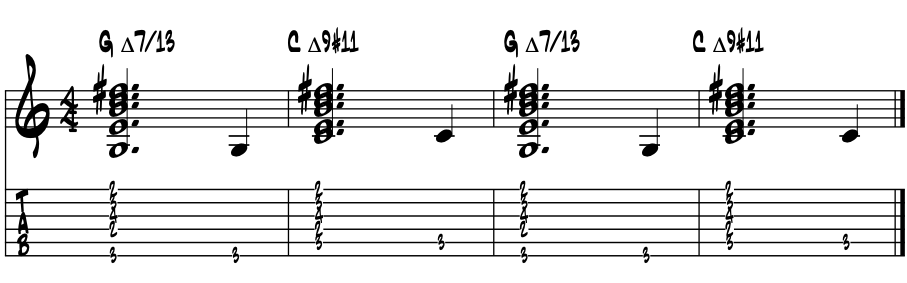

'moving the #4 tritone up an octave ...'

|

'Sharp Eleven' (#11) in a nutshell. The #11 colortone, created by simply moving the #4 / b5 moved up one full octave interval, now looses its whole step clash with the major 3rd in each of the three diatonic major triads we find within any of the 12 key centers. Atop the One and Four chord arpeggios, #11 brings a whole tone's aural color and a reshaping of their tonal stability by now having two major triads within one chord. And on the Five chord, the various dominant V7#11/13 colors can support combinations of an augmented triad and a double tritone pairing of pitches / intervals in the chord. |

Complex ? U bet. Every once in a while these '#11 potentials' find their way into a pop song, but mostly we're jazzing it up here, and yet in theory we are ascending towards both the polytonal possibilities and into '12 tone' serialism and the newer 'chromatic buzz' of all V7 of the modern jazzers. |

|

So why an augmented 11th? With a perfect 'octave and a half' interval above our root pitch, we locate the sharp Eleven / #11. Retaining its essential tritone DNA from #4 / b5, it lends itself in similar ways to it's octave down counterpart, yet in melody and chords, and a key center, #11 adds in some new twists. Where as the lower tritone tended to diminish ours sounds, with #11 we tend to augment and open up polytonal ideas in a major key center. |

When altering our three perfect intervals; the fourth, fifth and octave, traditional theory dictates that we use the musical term 'augment' to enlarge or 'diminish' to reduce their size. This initial change is always by half step up or down. |

So in creating our sharp Eleven interval, we simply augment or increase the natural 11 by half step. As with the natural 11, harmonies written to include the #11 will in theory have a 7th and 9th also. Examine the pitches to locate the #11 above our root pitch C. Example 1. |

|

The #11 rub. With a major triad, the '11th' runs sharp, thus '#11', most often to avoid the half step rub with the major 3rd of a major triad. For 'E' up an octave to 'F', the natural '11' gives us a minor 9th interval span, so not your typical tonic chord colortone. |

Theory names: augmented 11th, sharp 11. Increasing the natural 11th by half step opens up a new series of colors which lean towards the whole tone / polytonal landscape. Surely this is mostly in the jazz domain as our sense of tonal gravity and aural predictability evolve. On occasion, these #11 colors will find their way into well crafted pop songs, nearly always as an altered Two chord. From the root pitch 'C', examine the basic intervals followed by the whole tone scale. Example 1a. |

|

Sounds like a tritone. And indeed it is. Hear the tritone quality in both the #4 / #11 intervals? Measure three whole steps ( tri-tone ) up from our root pitch and we're at the tritone. We simply transpose up an octave to sharp Eleven and voila, we've got us another tritone. |

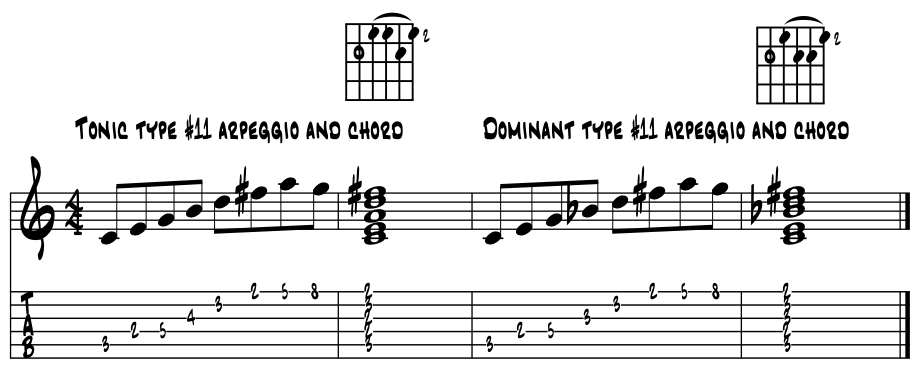

So where is this #11 colortone in the music. While occasionally in pop music, sharp Eleven is truly a jazz color. In both style settings, we most commonly find #11 as a colortone for tonic or dominant type functioning chords. For once we alter the diatonic natural 11 to #11, we no longer have the half step / b9 sharply dissonant interval pairing with the major third. Please examine the pitches and sounds of sharp Eleven. Example 2. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

C major / #11 arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

F# |

A |

C |

|

A subtle difference. Initially there's not too great an aural difference in these two colors. Of course both their triads are major, the key pitch shift in the arpeggios is the tonic major 7th lowering to the b7 of the dominant chord. This one pitch is the theoretical game changer between these two essential American components. Let's explore each one a bit and see what's what. Example 2a. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

b7 |

7 |

9 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

C major / #11 arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

Bb |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

Tonic type chords / sharp (#)11. Tonic chords that feature the sharp (#)11 can open up and 'legally' expand the sense of tonal center beyond its diatonic boundaries. Did you pick out the D major triad, 'D F# A', in the upper part of the chord in measure two of the example just above? Do check it again for the D major triad pitches if necessary. Here's the arpeggio letters. Ex. 2b. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

C major / #11 arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

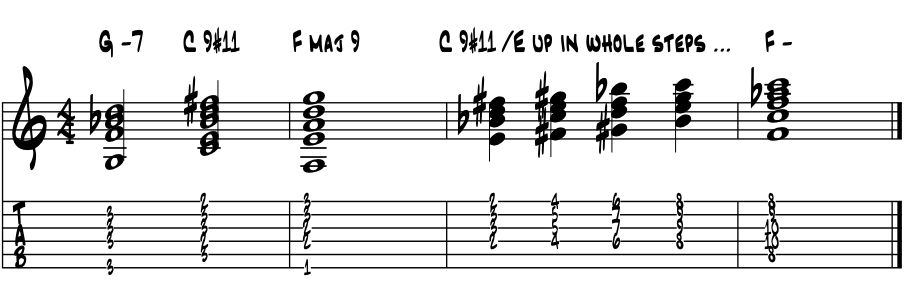

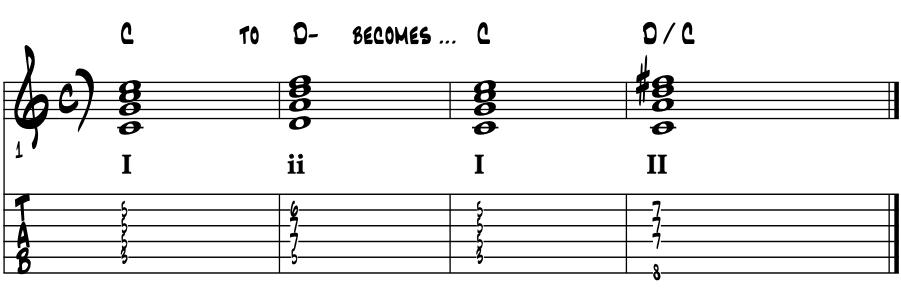

Pop / #11 on Two. Excluding for the moment the range of these colortones in jazz, a most common spot of the #11 is to use it to alter the diatonic minor Two chord to major. Our chord progression can thus evolve in the following manner. Example 2c. |

|

Catching something a bit 'out there' in bar four? This basic alteration is not uncommon as it also becomes a Five of Five motion when 7th's are added. In the last idea, just sounding the triad, sans 7, makes it more of a pop sound. "Against All Odds', which went #1 here for Phil Collins back in the 80's, features this chordal color. "Somewhere Out There", which went to #2 for Linda Ronstadt, also features this unique chordal color in the hook. |

|

While written music that would thoroughly explore this 'two tonic realm' is clearly off the bigger picture radio playlist radar for most, it's far more common in modern day to day improvisations among advancing players. Some cats will find it and get there in every solo (?). For when sounded, it creates a respite from the original key center and its sphere of tonal gravity. Which for some artists is just where the hang is. |

Generally available compositions such as the jazz essential "Blue In Green", by pianist Bill Evans opens with a written tonic #11 chord, using its 'floating' environment to gently set the piece in motion towards its core center of D minor. As tonic # 11 is the top of the tune, it refreshes and re-invents each new chorus of its written 10 bar form. |

|

Its recording, on leader Miles Davis' "Kind of Blue" album, captures what was then something sounding quite new and astonishing for the times. As a ballad, there's just such an aural clarity that was captured of such prominent American jazz artists and their art. Since its creation, intermediate to advancing jazz artists have thoroughly explored this composition, and full album, when seeking new enlightenments and to reset artistic defaults. Listeners and dancers too, as "Kind Of Blue" has been a top seller all along, since it's release in '59.' |

|

"Goodbye Again." This next composition was written to capture and portray the heartbreak of a love lost, then refound yet then lost again, creating a cycle of rebirths of love between soulmates. The opening chord in this work is along these lines of #11 and polytonal, to create the unknown yet curious atmosphere for what is to come. Click the gitfiddle to hear the piece. |

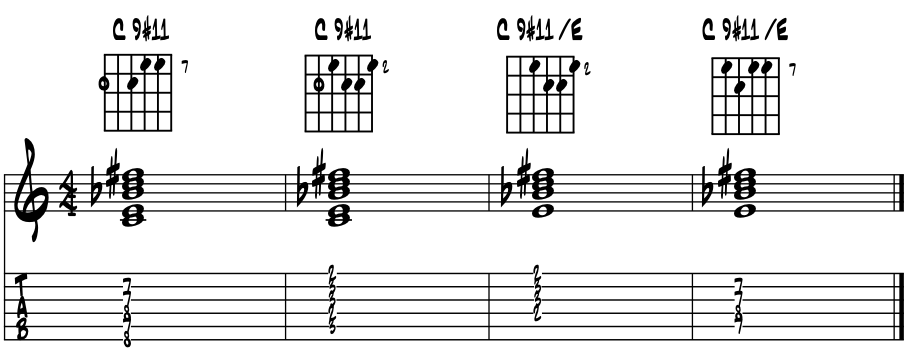

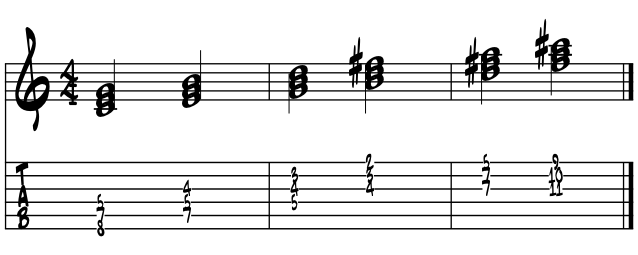

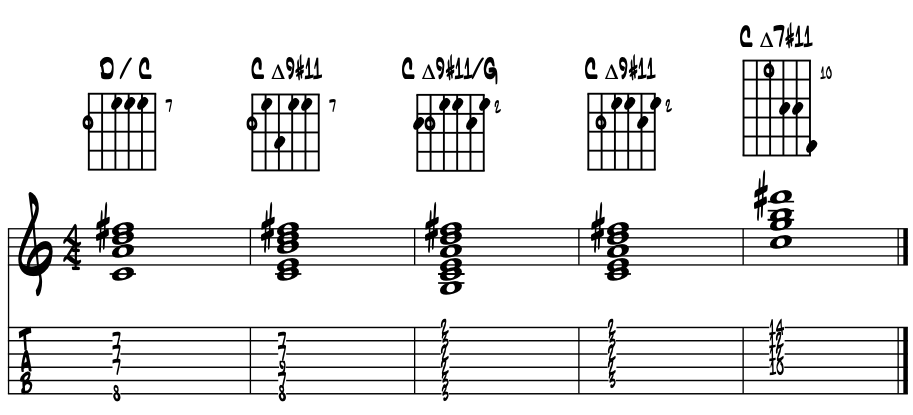

Tonic type sharp (#)11 voicings. The following #11 chord shapes are root position chords from the 6th, 5th and 4th strings. All these chords work as tonic function / #11 chords, combining a tonic sense plus an easy polytonal way beyond the diatonic realm. As like shaped chords will often do, they themselves make for a cool 'mix and match' group for creating phrases, as the counterpoint of the inner voices often suggests possible combinations for phrasing. Try running these in the order presented, see what shakes loose for ya. In 'C', ex. 3. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

tonic #11 arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

|

Hear anything cool? These chords may take time to assimilate onto your palette The last one easy an easy major 7th evo. |

Tonic #11 chords in action. A fairly common spot for these chords is on the final hold of a jazz arrangement. While it sounds kinda lame, it is a spot to begin to use the color, sound the chord confidently, etc. The absence of a solid resolution leaving the listener with just a wisp of future expectations and artistic explorations. We can also use the tonic #11 to delay a resolution, so in a sense a suspension that often occurs on the downbeat. Modern cats use these tonic colors as their tonic, reveling in the sense of an ambiguous key center sense of tonic. Which of course to them it is not ambiguous :) Here's the delayed resolution idea. Example 3a. |

|

Tonic #11 chords sure make a lovely modern Four chord too. It's been said that motion to Four is as gospel as it ever gets. Well, these last few voicings work rather nicely as diatonic Four chords. In this next idea we do just that. Create a vamp between One and Four by simply moving just our bass pitch. Although not really too gospel any more perhaps more of a modern bossa nova vamp. In G major. Example 3b. |

|

Hear anything cool? Thump the bass note, play the chord. Generate a melody from a parent scale. |

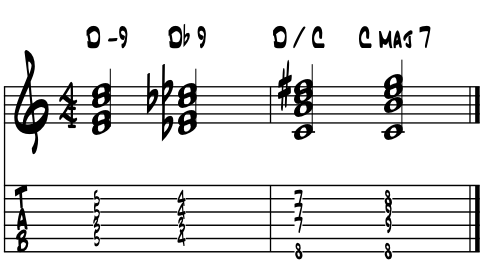

Dominant type chords / sharp (#)11. With the flip of one pitch we change our basis, from tonic to a dominant type chord; major 7th to minor 7th. So these dominant / #11 chords can potentially possess two tritone intervals which often imply diminished, and can also have an augmented triad in their configuration, thus the wholetone possibilities. Crazy huh ? Please examine the pitches and their sound in chords, thinking from the root 'C.' Example 4. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

b7 |

9 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

C7 #11 arpeggio |

C |

E |

G |

Bb |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

| tritone interval | C |

. |

tritone |

. |

F# |

. |

. |

|

| tritone interval | . |

E |

tritone |

Bb |

. |

. |

. |

. |

| Bb augmented triad | . |

aug. triad |

Bb |

D |

F# |

. |

. |

|

Sound the same? Do these chords sound mostly the same to you? No surprise really as when the whole tone color is involved, it truly can dominate the sonority of a chord. So these last few chords are essentially the same, just different shapes starting from different strings. |

The chord in the third measure is perhaps the most common augmented chord shape. Here in first inversion, so the major third of the chord is its lowest pitch. It also moves up easily up in whole steps as a constant structure, advancing its linear motion and key center resolution capabilities. |

In this next idea, we first resolve the V9#11 chord in a fairly common manner then use its whole tone properties to ascend to the tonic minor. Example 4b. |

'2 4 6 8' ... who do we appreciate ... whole tone ! And the tritone too :) |

Sharp Eleven (#11) as the final hold. In the world of day to day jazz performance, oftentimes it is based on the idea of 'arrangements while you wait.' All this really implies is that the leader of the gig creates the arrangement for the song. While this may sound open ended, which of course it can be, oftentimes seasoned players of really any style, especially those folks who have worked some together, will know how this thing is going to mostly work out, even if the song title changes. |

Standard format for standard tunes. A standard format would be to use the last four or eight bars of the song as an intro, read the tune down, oftentimes twice for brighter tempo melodies or 12 bar blues, a round of solos, then head just once and tag or coda. |

|

The tag could be many different things. Last four bars played three times is common. Creating a Three / Six / Two / Five vamp is cool going out as it gives another chance for players to blow over a common cycle of chords and find an idea to end with. Maybe the melody? Maybe, there's lots of ways. |

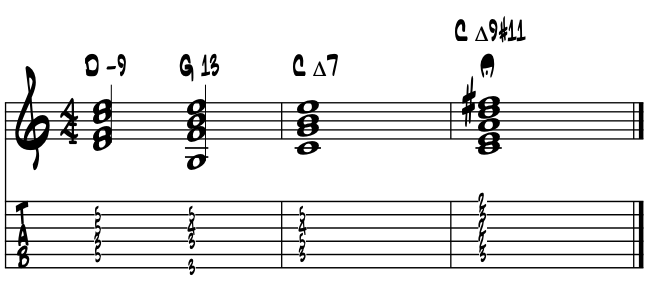

Final hold / tonic birds eye. Thinking in a major key, the close of an arrangement is usually a cadential motion to the original tonic key of the song being performed. Once that chord is struck and held, it's not uncommon for jazzers to slip a tonic #11 chord as the final hold. It just creates that wee bit of something that gently trails away and fades to black. Example 5. |

Final hold with V 9#11. In this next idea we do a similar thing with our #11 color with a few twists. We use a very common lick to end the tune and the V 9#11 as the final hold. The voicing might be a lot to quickly grab at first. So if you've a bass player on the gig, maybe leave the root out or assign the root pitch to another. As a single, just thump the bass and play the top four notes as a regular chord. So, whatever it takes right? Ex. 5a. |

Cliche. With or without the V 9#11 chord, we can find this blues lick and near endless variations throughout our Americana songbook. No style is immune from its presence. Well, probably. Not sure if the metalist cats ever use it. Regardless, perhaps learn it from a couple of different string sets and plug it in when Ya need it to close out a tune. Variations? Potentially endless, based on your chops, but even the vanilla version included above, properly sounded in pitch and rhythm, most often will work like a charm. |

Tonic sharp Eleven arpeggio symmetry. Another neat thing about our tonic sharp #11 color is the perfect weaving of the major and minor 3rd intervals in it's creation. Termed tertian harmony, while the vast majority of our arpeggios and chords are constructed with the major and minor thirds, rare is the alternating interval symmetry as found with our tonic #11 colors. |

We can verbalize the following chart by thinking that C up to E is a major 3rd, E up to G is a minor 3rd etc. Dig the pitches, the interval symmetry and their sound in C major. Example 6. |

arpeggio degrees |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

#11 |

pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

| intervals | maj 3rd |

min 3rd |

maj 3rd |

min 3rd |

maj 3rd |

That last chord is a piano voicing yes? Pretty much. With so many pitches, so close to one another, it's either a piano or an orchestra to sound these combinations! |

Symmetrical interval construction. Our system of music theory and its modern tuning allows for us to create evolutionary new and exciting artistic ideas with perfectly uniform patterns of construction. Like Coltrane's "Giant Steps" was in the later 1950's? Yep. |

So we can we open up new avenues for theoretical and artistic exploration with the perfect interval symmetry. Does the symmetry of the thing make it sleeker? It might. And is sleeker faster too? As when the Four chord evolves towards Two? Setting up the chromatic bass motion of the tritone sub? Can we accelerate the perception of time without actually going faster measured by the clicks? The arpeggiated symmetrical sequencing of major and minor thirds, is perhaps another such component to explore. |

We've just a few more stops along our numerical discovery pathway and two will have this uniform symmetry of construction. While one will provide another unique and modern tonic functioning color, the second will enable us to open an entire new realm of theoretical potentials. Stay tuned and keep reading :) |

That last chord voicing. So the chord at the end of the last idea is quite a handful for guitar. So to sound it out we can split it into a few parts. Once divided we can choose the when and how to reassemble it up back together. This one idea or approach to sounding these 'pitchier' colors can open up a vast portal to exploration for the modern, evolving guitarist. |

In another discussion here in Essentials we'll employ this chord voicing technique as we create a new system for tonality and composition. Here's the above tonic #11 chord broken down into three note sections and sounded out. In 'C' major. Example 7. |

Just superimposing triads? Yep, pretty much but the trick of it is in the perfect symmetry of the interval construction. And how this symmetry can lead us from one tonal environment ( usually major or minor ) into another. That we can do this without any real sense of the V7 tritone cadential motion we've enjoyed and employed for the last four centuries or so, is an evolutionary direction for our future musical systems. Evolve from within. |

Is there a flip side to this symmetry? Absolutely. Our Yin / Yang, major / minor two is flippable. A sequence of minor 3rd / major 3rd yields the beautiful Dorian arpeggio beloved by so many. The 'modal' period in American jazz during the later 1950's and forward featured this Dorian color. Please examine the pitches of this sequence, now from the root pitch 'A', the diatonic relative minor of C major. Example 8. |

|

That chord belongs in an orchestral score. Sure does or even just a piano with a pedal ! Special coolness lives in that last pitch on top. By correctly following the sequence of intervals, that last C# signals that we're really not in Kansas anymore. So we've symmetrically arpeggiated ourselves right out of our key center? That appears to be the case mon ami, and while the loop closed itself at 'A' two octaves up, our next pitch in sequence is indeed a major 3rd. So, an arpeggio that evolves from the minor into a major key center? Yep. |

|

Review and forward. Our #11th chords can create that sense of floating, of something not quite finished or seemingly unbalanced. Like some mobiles. Perhaps that's why we often find a dominant chord type V9#11 as the final chord of a jazz arrangement, to leave things up in the air a bit as to what might be coming next. |

Tonic #11 chords often are used to simply delay the resolution to a more definite sense of tonic. Although in more modern music, the #11 is the tonic color, as the artist is wanting that sense of being not quite settled or resolved in their tonal destination. |

The interval / arpeggio symmetrical sequence we use in creating our #11th chords, if continued just a wee bit more, will ascend to create a portal which opens up into a new dimension for our creative endeavors. Not really sure of what is there but perhaps the next generation of music theorists and composers will create the music that heals our world, of the often senseless tragedies and unrelenting sadness for so many in our times. |

"The greatest discovery of my generation is that you can change your circumstances by changing your attitudes of mind." |

wiki ~ William James |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"Life is about creating yourself." |

wiki ~ Bob Dylan |

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

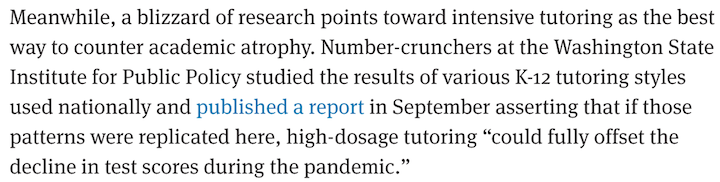

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |