~ the now ancient puzzle of twisting the global tuning pegs of the pitches to max their magic of all cultures through the ages through all 12 keys ~ 'the weaving together of ancient and modern tuned pitches creates our Americana musical pitches :) |

"What is remarkable about Western music is that by its chosen scales, modified through equal temperament, and by developing complex forms and complex instruments, it has raised the expressive power of music to heights and depths unattained in other cultures." J. Barzun |

|

In a nutshell ~ evolutions in tuning. That said (above), the central theme here is correlating how a finer degree of tuning each of the 12 pitches encourages the evolution of music from a historical sense. So history, 'science math theory' and each era's styles all merge creating both a pathway of learning and a historical time line too. Two for a nickel :) |

The author's catalyst. So, many decades ago my theory professor at college Dr. G. Belden, stated in regards to Euro classical music, that 'we can better understand a historical musical style by examining the system of tuning in place during that historical era. For how finely the pitches were tuned creating the pitches, determined what instruments were available from which created the music of an era.' This plays huge in our understanding of the music theory of the Americana weave of musics, as our 'blue tuned' melody notes ride atop 'equal tuned' pitches to create harmony; two unique sets of pitches tuned their own way blended together. Thus, in the following discussion we'll simply examine the historical evolutions of the tuning of our pitches. We'll need to include both geography and mathematics of the earlier tuning systems and theories, so as to tie our own Americana musical sounds of today in with the global music community. |

In Americana musics. Our Americana musics are unique from all others in that some of our most prominent melody pitches come from the older ways of tuning the pitches. These we can term today our blue notes. We then sound these colors over the 'new' precision of tuning, found in chordal instruments, so the fretted string instruments and pianos mostly. Often termed throughout this work as the 'blue's rub', melody pitches slightly out of tune with one another get rubbed together with reckless abandon over chords built with exactly tuned notes, well most of the time :) |

Pure major 3rd; 'tuning super trade-off.' The nub in all of these tuning developments really boils down to the quality of the third scale degree above the root pitch, in both major and minor, but mostly the major 3rd. For when we 'equal' tune up the pitches to create chords, our thirds are tempered just a wee bit sharp in comparison to the pure natural pitch as created by the division of the octave into the simple 5:4 ratio. This 'sharpness' of the major third was simply unacceptable when first postulated within a tuning scheme during the 16th century in Europe. |

Artist's with the keen radar back in the day, around the 1600's or so, simply could not accept this 'wee bit' of tweaking of their pure, celestial major 3rd, even if it opened the door to the complete, full spectrum of harmony that they knew was within reach. Musicians danced around this for a 100 years until composers finally got a real deal 'piano / forte', with the loud soft touch sensitive key mechanism as originally built by Christofori in Italy, in 1700. |

|

For once European composers had a keyboard instrument whose individual pitches had the fully nuanced expressiveness of touch for each individual piano key to control the volume of its pitch, some wanted this new expressive ability built into a keyboard instrument that also had no tuning limitations for the range of chordal harmony they knew was available. And they wanted it in every one of the 12 paired key centers; the diatonic major and minor and all color tones. |

What we gain. Ideally a perspective how our present day pitch resource evolved to energize curiosities for further explorations in tuning up the pitches. For guitar players this includes open tunings and the pitches we create through the bending of strings and using a slide on the strings. And also from this vantage point, a way into how our own Americana musics evolved over the last 100 years or so and that in theory, it is this combination of 'equal' and 'blue slide' tunings that have historically created our Americana sounds and musics. |

Theory closure. This tuning discussion is part of the theory core in UYM / EMG and is all about creating closure while getting to the theory center of the topic. Save the best for last? Maybe. Regardless, for without precisely tuned pitches our modern musical world begins to wobble right quick. So into the wayback we go to when we lived in caves and where the community campfire just might have been the best gig in town :) |

Overview / harmonic series. The tuning systems we use today to create our pitches come from just a few sources. And while there have been numerous tweakings over the centuries as our music, its evolving instruments and composers have demanded, we still for the most part have simply adapted our tunings from the natural ordering of the pitches that Mother Nature originally provides. |

These originally sourced pitches from nature still provide nearly all our pitches today. And while we still often look to find their natural tuning in our music today, we theorists have also tweaked their tuning to accommodate our modern ways of making music. |

What goes up ... This natural state of creating and tuning our pitches is generally termed as the harmonic or overtone series, and its sequencing and tuning of our pitches has been available to us from any taught string or column of air since the beginning of time. Please examine the ascending pitches as created by the naturally occurring harmonic series with the low C as our fundamental pitch. Example 1. |

|

Once past the initial octave we've a couple of key elements here for sure. First, our first 'new' pitch is G, a perfect fifth above our fundamental root pitch. Is this the same perfect fifth that Pythagoras used to create his pitches? It's got to be. Catch the C major triad in the pitches numbered '4, 5 and 6' in the example? |

Must come down ... At least in theories anyway. So the perfect fifth that went up now comes down creating a new set of pitches. Example 1a. |

Catch the treble clef interval F to C of a perfect 4th? Or the descending F minor triad in the pitches numbered '4, 5 and 6' in the above example? Cool. In this next idea we combine the two series'. Example 1c. |

|

So these are the way the pitches naturally occur as created by nature. Explore beyond this brief illumination if your curiosities so demand. See the ancient diatonic scale in the pitches? No me neither, that we had to specially create for ourselves. But we do get the two triads, the major and minor balance of the energies, and that sparks it all off. |

|

Got this classic Americana riff under your fingers yet ? In 'C', the pitches of the major triad to close a day.

|

|

Neanderthal flute. A fairly recent archeological discovery made in 1995 in central Europe unearthed what is today commonly known as the Neanderthal flute. Although there is some serious controversy among scholars about what this fragment of a 'cave bear leg bone' shaped into a flute actually is, many believe it to be the earliest non percussion instrument ever found by us to this very day. |

With our modern scientific computer modeling we've created a complete version of this early flute, revealing that the fingering holes on the fragment would correspond to a section of our natural minor / relative major scale. Our own 'diatonic' scale? What we know as the white keys on our pianos ? Yep, exactly. So of course the finders of this relic have built full replicas and had woodwind experts play them. The results in expert hands ...? Melodies that stylistically include everything from J.S. Bach to Charlie Parker and a whole spectrum of pitches in between. |

Controversial archaeological ruminations plus modern computer wizardry for sure, but still simply a way cool thought to consider no? That the pitches with us today have created melodies for many many generations of our ancestors. If the pitches have been around for that long, our memories too might hold the melodies also. |

Thus might the tasking of today's artist include to find these ancient melodies and bring them forth into the new light of today, reminding us all of our ancient heritage? Check out Gershwin's 'Summertime' for an essential American melody created with these pitches of the diatonic natural minor scale. That these pitches are also guitarist Carlos Santana's 'go to' color nearly every time, who's melodies reach deeply and lovingly into our souls, stirring up the passion and compassion to love. |

|

~ a timeline of tuning up the pitches ~ |

'... the tuning of the octave interval has always been inviolate, it must remain pure ... what has happened in between is the rest of the story ...' |

A historical timeline of tunings. The following discussion creates a historical timeline to overview the origins of and evolutions in tuning, of the 12 pitches we use today. In our theory studies here, no more no less than 12, with no real competition on the near future pitch theory horizons. |

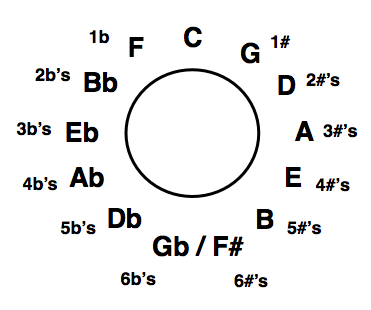

Pythagorean tuning / by perfect 5th's. Again into the wayback we go to ancient Greece nearing the end of the 6th century B.C., where Pythagoras and his scholars, who will go on to become rather famous mathematicians, have devised a system of tuning quantified by mathematics, using the interval of the interval perfect 5th. The original music and math? Probably yes. By creating a succession of perfect 5th's from their root pitch, as based on the ratio of 3:2, the 12 pitches of our chromatic scale are mathematically born. |

Unfortunately, their last pitch to close the loop and their starting pitch were simply not the same. It's quite a bit sharp, 25 cents, so a quarter tone of of modern pitches. Known as the 'Pythagorean comma', theorists who followed after would seek to unravel this mystery for a couple of thousand years. As for the music they created, as far as we know today, one single melody line which was thought to be descending, written in one key without any type of chords to back up the line. |

|

Aristoxenus. Again into the wayback we go to ancient Greece but forward a bit into the 3rd century B.C. Here we find Aristoxenus, who wrote a treatise Elements of Harmony. Although only an incomplete copy remains of this work, it is our one real window into the systems of music that the early Greeks employed. |

|

Here we discover a well developed melodic system of tetrachords, groups of four pitches where the outer two pitches are fixed, usually spanning a perfect 4th interval, while the inner pitches are adjustable. Combining two perfect 4th tetra chords with a whole step between adds up to our perfect octave interval. |

Aristoxenus maintains that the true way to tune intervals is by ear, by what sounds good and not solely by mathematics. So we see the beginnings of the controversy between the tuning our pitches by mathematics or by ear. This debate will be carry forward by succeeding generations nearly two full millennia before arriving at our current system of tuning. |

"Just intonation" / perfect 5th's / pure major 3rd's. Along around the early decades of the 2nd century, Ptolemy of Alexandria, Egypt brought forth his ideas for tuning our musical pitches. His system comes down to us today as 'just or pure intonation.' Ptolemy added empirical thinking, i.e., observation, probably getting together with the area musicians, and found a way to translate musical intervals into ratios and vice versa, ratios into intervals. |

|

What this gets us is a way to find 3rds, 4th's and 5ths etc. in relation to a tonic pitch. Like Pythagoras, Ptolemy was said to use a monochord in working things out and that ...

Which of course it does this this very day. So we see the emergence of a mathematical way of creating the pitches for our major scale. The pitches of just intonation are created by using ratios of only small numbers. The purity of the tuning creates pitch combinations, intervals, that have no beats, thus they are 'pure.' This way tuning of the pitches makes for beautiful melodies, and did so for near 2000 years or so. So from way way back and till today, when we 'bend' our notes to suit our Muse and the art we create together. Also know that these same pitches will run into tuning trouble when stacked into chords and further developed diatonically into a key center for homophonic composition. Best is to combine tunings and let each add their own unique strengths. In theory, there's only 12 pitches on our Americana palette, so variables help fine tune yes ? And we invented the blue notes too ! The masters of which know their variables true, in pitch, life and near everything we do, we all share some blues. |

|

So a system of tuning that was in a sense organically grown in the times they lived and the available understanding of the mathematics of tuning of their day. While just / pure intonation does create a pure third and fifth within the diatonic scale, the other pitches of the natural scale derived from this purity are said to be lacking when taken as whole. Know any three note, '135' melodies or motifs ? Traced back to our second century and Ptolemy, it survives up through the early Renaissance period, 1400-1550, in Western Euro music. |

|

Mean-tone / 'narrow 5th's.' In the later Renaissance period, 1550-1700, mean tone tuning evolved. This tuning scheme simply tried to improve on the pitches of just intonation so as to allow more of available key centers for adventurous composers of the day, up to three sharps and flats, to retain a better purity of thirds and fifths. This was done by reducing the interval of the fifth's by just a wee bit, trying to get the Pythagorean 'comma' out of the pitches. Thus we see the beginnings of our first 'tempering' of the pitches. So what musicians gained was the ability to include multiple key centers within one composition. Termed modulation and perhaps needless to say, this had dramatic consequences for the evolution of the music. |

We also see the development of harmony during this era. The lute's 'rule of 18' construction is a close approximation of equal temper tuning, thus 'in tune' diatonic chords and arpeggios supporting melody as well as chromatic passages are possible. This gets us around the top half of our cycle of fifths. So six key centers to go. Example 2. |

|

Well temperament / some keys better than others. Towards the end of the Renaissance as the age of Enlightenment dawns, a further tweaking of the pitches occurs. Created by German organist Andreas Werckmeister (1645-1706), the basic idea was to create various tunings to displace in various ways the 'comma' first identified with the Pythagorean tuning. |

|

A contemporary of Baroque monster J.S. Bach, Werckmeister's 'well temperament' appears in the title of Bach's "Well Tempered Clavier." Created in two volumes, the first thought to date 1722 the 2nd in 1744, Bach's collection of works contains a composition for each of the 12 major and minor keys. A controversy exists to this day as to whether the well tempered or equal tempered system of tuning was employed on Herr Bach's clavichord / piano. |

|

Equal temperament / birth of modern harmony. This is the last evolution of the tuning of our original 12 pitches. It comes to prominence in the early 1700's as the homophonic style of composition, one melody line supported by chords, becomes the new dominant texture of European music. This tuning and style is then brought to America during this early era and thus provides part of the melody and all of the chordal basis of our Americana sounds. The indigenous part of our Americana melodies is today mainly based in the blues stylings. And while the blue notes are of course available from equal temperament tuning too, in performance they are more naturally tuned through bending and vibrato. How natural tuned pitches combines with precise 'tuned' chords create the 'blues rub', that character 'blues hue' of purely an American invention. Once pianos became popular in churches during the 19th century, the original spirituals songs become gospel according to those testifying, the rest is our beloved music history :) |

Equal temper tuning simply divides the octave into 12 'equal' pitches. Using the solution of the 12th root of 2, we can locate each pitch within the octave both by numerical frequency of pitch or by physical measure of string length. All pitches are equal to one another and as such, each will fully function as a root pitch for a complete diatonic key center. We use this same method of tuning today in our Western music. Anything midi is probably the best example of this mathematical tuning although all of our modern instruments follow equal temper guidelines also. |

At the dawn of the 18th century, Italian builder Cristofori has created the piano forte, that lovely keyboard instrument that allows for the struck keys to play various dynamics of volume. This evolution is the real game changer. For composers now had an 'emotional nuance' ability for their ideas and soon were insisting upon having the ability to play in all the keys 'equally' in tune. By then the mathematics to achieve this was known and eventually equal temperament won the day. While critics raged about the 'out of tune' quality of certain intervals, especially the major 3rd being noticeably sharp (six to eight cents depending), equal temper's 'anything from anywhere' chromatic abilities eventually won that day and is still, today, the basis of how we tune our pitches of nearly all of our instruments. |

|

MIDI. Empowered by a couple of hundred years of a glorious and so varied catalogue of music all written in equal temper tuning, folks thought that this tuning will be around for a while. So a next natural evolution, through more math calculations, has digitized the frequencies of equal temper tuning into midi data thus able to be processed by computers. So now we still get the full palette of musical colors but with the push of a button, and we can do it with any recordable sound available. |

|

American tuning / combining two tuning systems. Our American mainstay tuning system is of course 'equal temper tuning' as just described, whose degree of accuracy creates the pitches we need to work nearly all of the magic; most of the melody pitches and all of the chords. Our second system is the much older 'just' tuning, which helps to contribute and help us find the variably tuned blue notes. While we can find all the blue notes in equal temper tuning they need to be rubbed to bring extra magic. For surely as the blues music and its magics come right out of a well tuned piano, we know it all can be there. Yet, the 'justly' tuned blue notes provide a wider range of what is termed here the 'blues rub.' So a deeper degree of 'out of tune' quality, rubbed against the pitches within any chord, which are by necessity tuned to the mathematical exactness of equal temper tuned up pitches. Cool ? That we each get to find our version of the blue notes and their rub is the coolness we look to seek out and better understand. |

Creating a theory closure. Having a sense of the basic of how we tune our pitches from preceding ideas, this next discussion simply looks to get at the nuance of pitch and tuning that helps to give Americana music all of its unique flavors and combinations. |

While nothing in this discussion will change our core theory principles, and in truth they haven't really changed for a couple of thousand years now, what changes or perhaps better said, what has evolved over the centuries, is our perspective of pitch through discovering and applying new mathematics and science, that has allowed us to more finely tune our pitches and build an evolution of musical instruments to sound them out. And while this mathematically based science evolution has expanded our options, it does comes with an artistic price to pay. |

A new correlation of pitch and style. As with our theory correlation of number of pitches and musical style, we can attempt to make a similar parallel with how pitches are tuned. For surely one of music's most magical and transcendent aspects is in its ability to transport, we the listeners, to the cultures of many global peoples, through to their historical times and geographical places. To set the mood? Exactly, to set the mood of ... |

And while Hollywood movies surely has had a creative hand in recreating these cultural sounds and image combinations, we as theorists should also realize that music of an particular era was created by pitches played on instruments whose pitches were tuned their own unique way, by the players of those times and cultures working their musical heritage magics. |

So when we hear music reminiscent of the American West days and Native American Indian voice, flute or drum music, we'll probably visualize these peoples. When we hear the Elizabethan polyphonic music of the 1600's during the Winter Holiday season, we might visualize scenes of those times. When we hear music of India, with sitars, tabla drums and metallic sounding drone pitches, we may visualize the Taj Mahal and those environs. |

|

Oftentimes our own neighborhood wind chimes can create the pitch combinations of the pentatonic melodies associated with Asian music with simply a passing breeze, yet in doing so might conjure one's personal image of temples and dragons of the Far East. Our own distinctive American blues has its own way of tuning and sounding its unique pitches that might conjure a rural dusty crossroads or street scenes from New Orleans of our own American heartlands and cities right here at home. |

|

So each of these unique sounding musics, when originally created by their own peoples on their own indigenous instruments, are created with pitches tuned their own unique ways. And this creates the core of our own musical philosophy; that by joining in rhythm, all the pitches work in the making Americana musics. And the basis of this rhythm ? |

|

Why ... swing of course :) Count Basie "Jumpin' At The Woodside", swing !!! |

|

Overview / American tuning. With an initial distinction between melody and harmony. our theory musings begin anew. For in tuning the pitches of these two components therein lies the rub. Exclusive melody players such as singers and horn players, may inevitably adjust their pitch to best sound and portray the emotional statement of the line they're performing. With practice, doable. |

For there's surely room for slight variations in intonation, i.e., the tuning of a pitch, in finding the 'sweet spot' of a particular note in a particular line. One very common way they achieve this is by adding varying degrees of vibrato to the pitches. If we measure vibrato on a strobe tuner, we see that the actual frequency number of the pitch goes up and down a few cents ... or more as the case might be when achieving big rubs. |

|

Slight variations in pitch? Yes, slight variations of pitch when compared or combined with the instruments that the melody instrument is performing with. And if that accompanying instrument is capable of playing chords, such as guitar or piano, then there's a better chance of subtle differences in pitch between the two.

|

Do we hear it as being out of tune? Well, this can range from a no, absolutely not, to a more general no not really and then to well, they're really really pushing the tuning envelope. For in the modern blending of musical styles that have come before us, and forward together in our modern weaving of musical sounds, we dig this nuance in pitch. For it's a rather big part of what makes 'American music sound like American music.' |

Most recently, in the last 20 years or so, there's been a new interest in vocalists adding a more 'gospel' interpretation of the melodic line into really all of our 'popish' styles. Known also by the classical music technique called 'melisma', the coolness is created by adding in a bluesy sort of filigree of notes surrounding the various predominant pitches or cadential points of the melody line. Often these melismatic pitches are slurred a bit, so there's also a corresponding sliding of intonation of pitch. |

|

So where is the tuning rub? Well chordal instruments, to properly function and provide the full spectrum of harmony we've come to enjoy, must be tuned with a greater degree of precision to get all of this chordal potential to sound equally in tune all the time. And in this process, some of the sweetness of pitch that a singer or horn player looks for is potentially compromised. |

Compromised pitches ... really? Yep. And these slight variations of pitch and different degrees in the exactness of tuning pitch and intervals were super controversial in the 17th and 18th centuries in continental Europe. For as the various keyboard instruments developed and composers and players purchased them, they surely demanded that the instrument play in tune but in tune to what ... ; thus better tuned harmonies over a wider range and eventually all key centers. |

So any one specific controversial pitch? Any guesses here? If you're thinking along the lines of the major 3rd then you're right in the zone. Its companion major six is also in this mix. Six of course being the major 3rd of the Four chord yes? Motion to Four? Yep. For over the survey of our entire American songbook we'll probably find major key compositions predominant. Its major third interval carries the bulk of responsibilities for making things sound right and getting to the Four chord and back is the core of most of our harmonic journeys. |

If the major 3rd is out of tune ... you'll know it. So while an intune piano's major 3rd works just fine, singers and horn players might choose to soften their third ever so slightly, just a faint vibrato will often do the trick. Artists term this to 'warm the pitch up a bit' and the higher we go in registration, the tighter the vibrato will be. |

A balance. And if the major 3rd is crucial, the minor 3rd is too. An essential blue note, the minor 3rd defines the minor triad. Equal temper tuned, it'll sound flat, but just a wee bit. So give it a push and see what what happens. Give it a big push and enter into the world of finding your own blues hue :) |

And for us guitar players? Bending strings to find the sweet spots is potentially a huge part in the music. While not so much in folk music, any influence of the blue notes opens up the possibilities for bending pitches. Slide too? Yep, slide too bigtime. In my very early guitar playing days Richard Betts had one of the sweetest sounding 'bent to' major third in the biz, pure magic that sold a ton of records and influenced many who followed. With jazz guitar players not so much bending, until the fusion cats arrive, then the gloves come off as various electronic treatments such as fuzz obscure the tuning and bending is a dream. A big difference here becoming whether one is mostly playing / creating melodies ... 'over the changes or through the changes', and knowing of each help define the other. |

|

Cool so far? Curiously that the earlier European tuning issues were not only non-issues here but were super naturally acclimated here in the States, all simply by the way things were in the land that set in motion the melting pot of the pitches, and the eventual global appreciation of the Americana melting pot of musical sounds, styles and genres. This may be attributed to the fact that here in the States we merged many unique cultures. We simply made room for both systems and their pitches, i.e., tuned chords and flexible melody pitches, thus the equal inclusiveness of all artists as a center point within the American dream. |

Evolutions of tuning match evolutions of style. As modern Americans musicians today, we inherit three distinct compositional styles whose historical evolution coincides with developments in the mathematical systems of how the pitches were tuned. Into the wayback to ancient Greece to find monophony; one melody no chords. A similar sound to our own early Native Indian and African music. |

Back to the first millennia or so for polyphony; which eventually becomes a couple of independent melody lines, but still no chords. And then back to 1500's or so for the beginnings of homophony, which will eventually be one melody line backed with chords. Which is of course the way we generally still compose our music today. |

Our story begins anew. So if our music is only in one key, and is comprised of just one melody line, chances are we're good to go with a basic set of naturally derived, harmonic series pitches. Add a couple of independent melody lines together and we'll probably have to tweak our natural pitches a bit. If we want to have a few triads / chords to back up and support any combination of melody lines, we'll probably have to tweak or temper tune our pitches a bit more to allow us to stack up these pitches atop one another and sound them together as chords. |

|

Further, if we want a few of these chords in a few different keys to create variety within our music, further tuning tweakings to our pitches will be necessary. And if we want it all; all of the melodies, arpeggios and chords in all of the keys, and all on one instrument such as the piano, as we so often do today, then it turns out that we'll need a rather dramatic, modern tempering of our naturally occurring pitches to achieve this musical nirvana. But remember, not without some sacrifices of the naturalness of pitch. |

A question and summation. So has our overall evolution in tuning been mainly driven by wanting to have chord changes to back our lines and include all of our pitches into the mix? That seems to be the case. |

Anything from anywhere. For with today's evolved tuning we not only get a fully functioning instrument for creating 12 unique major and 12 unique minor keys worth of melodies, arpeggios, chords and rhythms, but we can still find the blue notes in between, simply by bending strings, using a slide or vocally enhancing the pitches we need to express the art in our hearts :) |

The sacrifice. The sacrifice we make in tweaking our pitches to gain our full resource is that in doing so, we subtly change the actual pitches in relation to one another from their natural state. The major third, a center pitch in so much of our music, was the sticking point in this for a couple of centuries in Europe during the Middle Ages into the Renaissance. |

The tonal difference between a pure, natural major third and its tempering to create a full system of functioning harmony becoming the core of the rub. Our modern tempered third is a wee bit sharp pitchwise from a naturally derived major third. We measure this difference as three cycles per second or 14 cents of the 50 cents that constitutes an equal tempered half step. |

In today's American music, in part thanks to our blues music and even just the blue note influences in any style, knowing about the tuning possibilities that have been created over the last 3000 years or so may help to understand our music. Luckily we've had the pitches we need since our earliest times in America, and to a greater or lessor extent, all of it perfectly built right into our modern six string guitars :) |

Merging the music of three peoples. In early America, three distinct cultures merged together, each contributing their own indigenous musics to our collective Americana sound, an ever evolving combination which we enjoy to this very day. Two of these groups, our Native Indian and African brethren, each brought the ancient natural tuned melody pitches. These are for the most part pure melody pitches. The third group, our European brethren of many nations combined, while also having the ancient pitches, also brought a more recent, more precisely tuned version of the ancient pitches with which we can create both melody and chords and mix these in any way imaginable. |

|

Turns out today that we generally assemble our music by combining pitches from these two unique tuning systems to create the American core of folk and blues from which most everything else 'stylewise Americana' flows unimpeded. Everything we needed pitchwise and tuning to make the sounds we dig most we already had from our most humble, modest and early pioneering days. |

The telling power is in the melody. Probably super biased to say but here at Essentials the melody is believed to have the best chance to convey the artistic, emotional content of the music. Subordinate to lyrics if that be the case, or a rhythm that sets a five elements mood, the melody's potential to tell the tale usually and traditionally reigns supreme. |

Tuning America's music past and present. So in a section of the popular Americana library of music of the last 100 years or so we've combined melodies created from an ancient lineage of pitch with chords, whose pitches come from a mathematically enhanced tuning of these same pitches. This combination of ancient and modern tunings on the same core pitches creates that purely unique Americana sound. |

American melody ~ just intonation. When we hear original Native Indian or African melodies, whether the chantings or singing of voices or the swirling winds of flutes, these pitches are initially tuned according to the pitches of our naturally occurring harmonic series. Termed 'just intonation', these pitches have an organic naturalness that our ears readily accept and deeply cherish. |

And if we follow along our harmonic series from its fourth and into its fifth octave, then consolidate our pitches to within a one octave span, we create a reasonable approximation of the 12 pitch chromatic scale. While these 12 pitches form the central core, there is simply not a high enough degree of tuning accuracy to allow us to stack these ancient pitches into chords, at least not to any degree that measures up to the fully functioning harmony of our more modern system of equal temper tuning. |

Music from other lands justly intonated. We look no further than the classical musics of India and Africa, the Gregorian Chant and Scottish bagpipes of the British Isles, the pentatonic colors of China and Japans, back to our own barbershop quartets even, that all include just intonated pitches. On and on to anywhere that a culture's pitches are derived and balanced mainly through the natural harmonic series. |

The musical textures we hear in their traditional songs most often combine strong melodies and steady rhythms. While harmonies are surely created among voices singing together, there are no true chords in a Western sense in any of these musics. Lower pitched tonic bass note or dominant pedal tone or pitches provide a bass line story for the melody to lean against. |

And here's the rub. So over the last 3000 years or so our European musical ancestors have been gradually tweaking the way they've tuned their pitches. The most recent artistic innovations in harmony of the last 200 years becomes part of our next catalyst in our tuning evolution. |

As so much of the world's doings embraced the sciences in the 1800's, we musicians too sought and found a mathematical solution to our existing tuning schemes. And low and behold, that by adapting a newer more precise math to our ancient original pitches, the ability to create a vast array of stacked pitches sounded together into chords begins a whole new era of musical art called homophonic music, a style we still thoroughly enjoy to this very day. |

The new math / equal temper tuning. In 'equal temper tuning', the original twenty four potential key centers, 12 major and 12 minor, now become fully functioning diatonic key centers, each equally capable in creating an endlessly astonishing array of melodies, arpeggios and chords, available 24 ~ 7, through limitless modulation and substitution. And if that's not enough, all of this tempered resource now becomes available on one new powerful and fully percussive instrument, Cristofori's piano forte.

|

|

Our recorded history also tells us that we guitarists today have for the most part have enjoyed this complete resource and its ability to create the potential of 'anything from anywhere' grandfathered in from our early lute ancestors. This inner, tempered versatility may also be evident in how the guitar family, and its theory as we know it today, has been able to survive fairly intact, or through its past stringed ancestors, all the way back to one of our three original American musical pioneering peoples, the ancient Greeks. |

As it turns out ... Our basic six string guitar and really anything with strings, is perfectly suited to merge these two tunings. For in properly fretted instruments, we not only get all of the chords in tune, we also have two very common ways to get at the ancient melody pitches. We can bend strings to find the sweetness or use a slide, both techniques having enduring legacies in Americana performance as the blues hue. |

Review; the essential difference. The essential difference between the two systems is in the degree of precision in how we divide the octave into its 12 parts and then understanding what we gain and what we lose. Greater precision enables us to stack pitches and sound them all together, i.e., our harmony, chords, the changes etc. For while a few key chords are also available in the ancient system, the modern tuning was developed and integrated to advance our system of harmony, driven on by our Euro composer brethren. |

Our modern sense of American chords first came over from Europe, probably in the form of written music. Books of songs for Sunday singing with a piano part. There was a piano on the Mayflower right? Regardless, this one aspect of chords clearly separates the music capabilities of the two basic tuning systems in use today. |

|

So in general terms, any music that has clear chords or harmony supporting a melody is from our more recently developed tuning system. We call this 'equal temper tuning.' Music that is melody centered without chords, is probably part of an older system of pitches tuned from the natural harmonic series we call 'just intonation'. Cool? |

"That's one of the wonderful things about science; not a one of us has to believe it yet it can still be 100% correct." |

paraphrased from a local bumper sticker |