~ Four ~ 4 ~ perfect 4th ~ IV ~ iv ~ XI ~ ~ the subdominate ~ ~ motion to Four brings our Americana gospel ~ '... and to our home away from home :)

~ the subdominant ~ Lydian mode ~ ~ motion to Four ~ a plagal cadence ~ and Four up one octave becomes the ... 'a rising of the spirits in our Americana gospel' |

In a nutshell ~ 'Four.' That our most common destination in any song of any style is to Four, should come as no surprise. For in both major and minor songs, the interval makeup of their triads and color tones are near identical. Thus, the 'stability' of home we associate with One makes going to Four just like a second casa. |

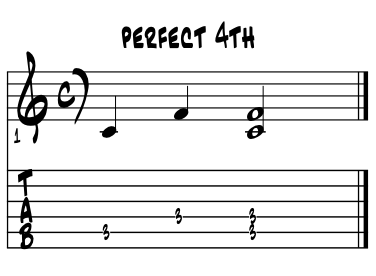

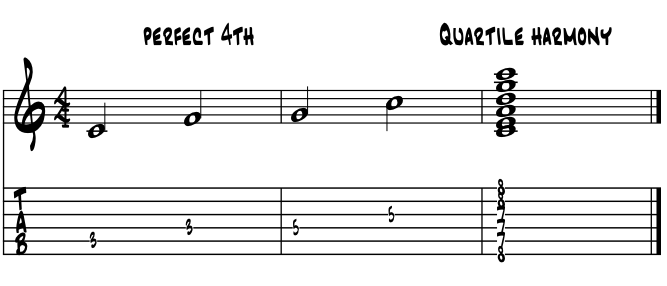

The interval of a perfect fourth is said to be 'perfect' simply by its aural purity when rung together with its tonic pitch. The purity of the octave, then perfect 5th and then 4th, form our interval / structural basis for help finding all of the other intervals. They, as perfect, just sound most pleasing of all of our possible combinations, and this aural perfection of sound is the founding basis of our entire system of music theory. We can trace this aural purity / theory foundation all the way back in our recorded history to antiquity. Based on their simple ratio of numbers and positions in the natural overtone series, the perfect intervals are the structural basis of the 'silent architecture' of our musics. |

"Blue Sky." A mostly three chords and the truth' Americana classic, "Blue Sky" is nearly all about the natural rocking (chair) motion between One and Four and Four back to One. Just a great folksy, country leaning, pure Southern rock love song of a story, with some solid, and some might say, historically 'essential' lyrical guitar playing. And it's the motion from One to Four, and back, that gets it all done. For country, folk, rock, lead guitar leaning cats, well worth a spin ... or 2. |

|

Theorywise here, we've three key aspects of energizing the discussion of Four. The first examines Four as a pitch within the diatonic scale; so melody and harmony concepts. The second is how closely Four resembles One in sound quality, colors and function in both major and minor within a key center. This is the basis for the third aspect of this discussion often termed throughout the discussions of this text as 'motion to Four'; that in most of our Americana musics, we are either somehow moving towards Four or have or started on Four, and we're working our way back to the tonic One. |

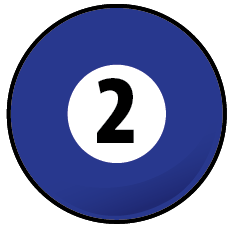

The subdominant pitch Four in melodies. These next pure Americana musical examples are based in C major. So, the pitch C is One, making the pitch F number Four. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 C D E F G A B C Locating the Four in a few lines here, can you 'name that tune' from just these fragments? This first one just might go way back into your memories. Example 1. |

|

|

Easy right? Cool. Here's a few more to ponder. |

|

|

|

|

|

Know these songs from these bits of their melody? Prolly do :) Learn their melodies here if need be. |

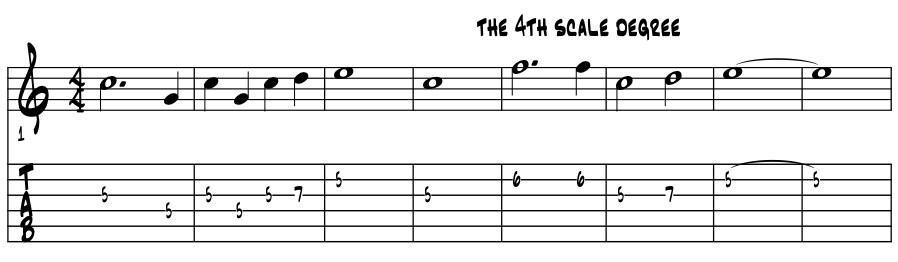

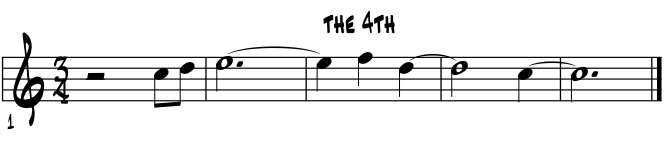

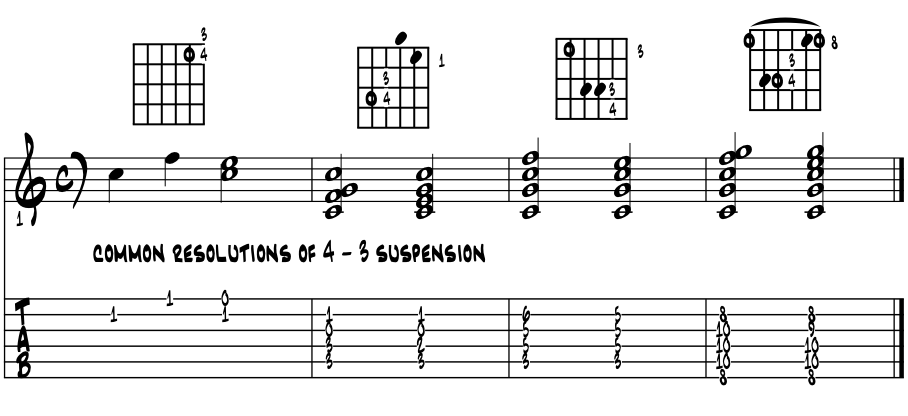

The 4-3 suspension. A most common and essential motion with Four is to hold it over a bit, creating that sense of 'aural suspension', before resolving to Three, thus its numerical name, a 4-3 suspension. We can locate it in most of our styles somewhere both major and minor, often used to dramatic effect. Here's the 4-3 theory basics in chord voicings. Example 1c. |

|

Hearing, sensing the gospel 'aaah ... men' in the music ? Cool. |

Perfect 4th / theory names and where in the music. And why termed perfect 4th? Termed 'perfect' by quality of its aural blending with its tonic pitch. That when compared with our other intervals, this perfect 4th just sounds nicer, really nice, perfect sort of nice. That 'perfect' flips, or inverts, the perfect fourth (p.4) into a perfect fifth (p.5) / interval shows it close position to the tonic also. No surprise we find Four in songs of all the styles, tempos, musical forms and genres we dig all through the centuries. |

For in storytelling, musical motion to the subdominant is as spiritually uplifting as we might ever get. Essential to the gospel sounds, it's also a central component of the 12 bar blues form. That Four provides a very similar diatonic sense of rest as the tonic / One, we gain a second resting point and respite, all while remaining within our original diatonic realm or key center. This similarity of chord / pitch quality holds true in songs written in both major and minor. And even as we ascend through their color tones, near all match. |

Lydian mode. The mode built on Four is Lydian, it's interval / pitch sequence goes all the way back to the Greeks. It's one of the four original modes we have record of; Lydian, Dorian, Phrygian and Mixolydian. Today, the Lydian color is a modern guitarist's dream come true as it provides a solid launch to polytonal realms and makes the tritone in V7 go away. We gain a major triad and the '-7b5' goes away. Think 'C' Lydian; CEG / DF#A / FAC / GBD ~ major triads EGB / ACE / BDF# ~ minor triads So, A tonic chord with two major triads, a 'C' major 9 #11 chord, a Five of Five, and a 'double major' 1 4 5 progression; for C major and G major. Modern cats also alter Lydian by lowering it's 7th, creating 'Lydian b7.' This group is a fave for some in improvisation in jazz as a substitute 'group' of pitches that sustains its own character in complex mixings of the pitches. Akin to the melodic minor group, we're as close to diatonic major as we can get ... and keep a blue 3rd :) |

So powerful is the Lydian color that it has its own book. Titled, The Lydian Chromatic Concept Of Tonal Organization, by George Russell, this work examines in depth the theory of and use of the Lydian group in American jazz from the 1950's onward. |

Americana gospel magic. The idea of gospel magic is simply that the melodic and harmonic motion to Four creates a depth of emotion like no other moves we have. In every music we have here at home as well as abroad, every culture and style can and often does have this same One to Four pitch motion and its effect. We just happen to call it gospel here in America. |

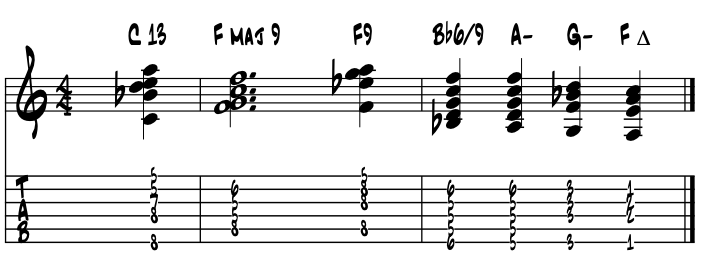

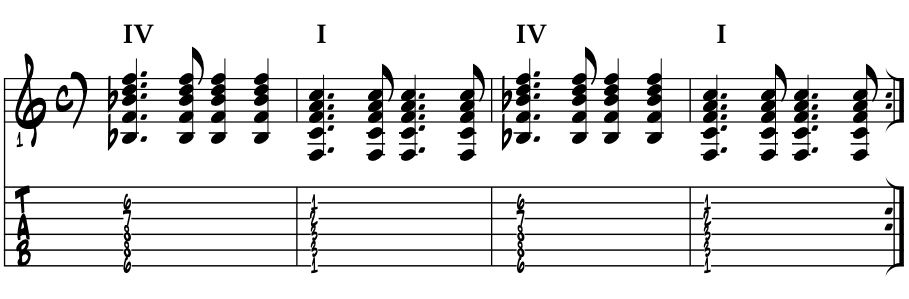

The gospel motion to Four. An essential core of all that is Americana music, the gospel sounds reconnect us with our natural roots for freedom and worship of the spirit of truth within us all. In this next song, once we establish our tonic, we swiftly move to Four and start the journey back to find a place to rest. In 'F' major, moving to Four / Bb, then back stepwise to our tonic 'F.' Example 2. |

|

Swing Low Sweet Chariot. Does it get any more gospel Americana than this lovely melody? The subdominant Bb 6/9 in the second bar is as deep, rich and loving as it might ever get for us wee mere guitar playing mortals. This chord melody is of course a bit on the blockier side of things but might be a good place to start for getting into this style of playing. Click the Swing Low link for the whole chord melody arrangement. |

The 'fast Four.' In nearly all of our Americana blues, the Four chord plays a super important role. There are two common ways this happens. The first move to Four is also a big part of the 12 bar blues form. It happens in the fifth bar, to begin the second four bar phrase. The second common motion is the 'fast four', where in the first phrase, we quickly move from One to Four in the second bar, then back to One for the remainder of the phrase. Fairly common in slower tempos to jazz it up a bit, here is the 'fast Four' motion. Example 2a. |

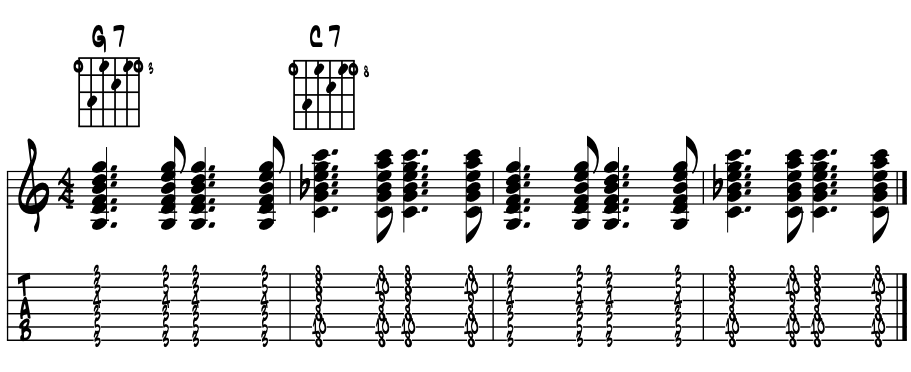

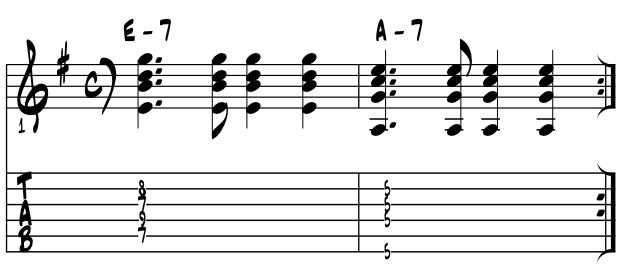

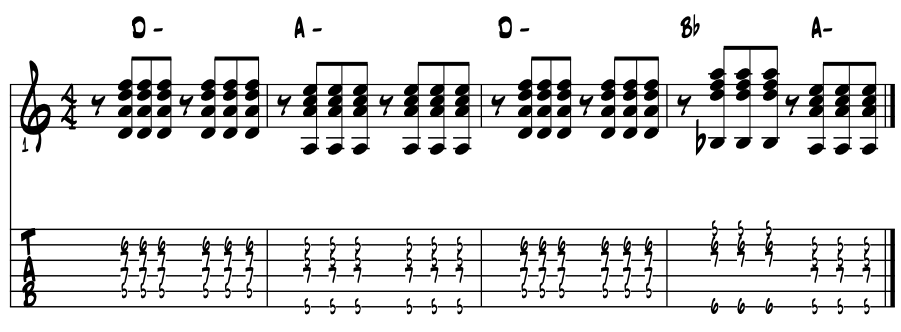

Tonic to subdominant vamps. Back in the early days of the funk stylings, songs such as "Feelin' Alright" by Dave Mason, come together simply with a cool vocal hook over a tonic One / sub-dominant Four back and forth vamp. While there are many variations, this motion we'll find in most of the improvisational American musical styles somewhere along the way, or make our own up too. |

|

In this next idea, based on a rhythm pattern, we vamp back and forth again using dominant chords for both One and Four. Make your own melody line, find a hook, write some lyrics. These types of vamps lend themselves well to the jam sessions we all love to partake in. Ex. 2b. |

Find the line. Cool with these changes? Barre chords can yield us a lot of music. These chord voicings in blues feature the hammer-on for the note on the 3rd string. |

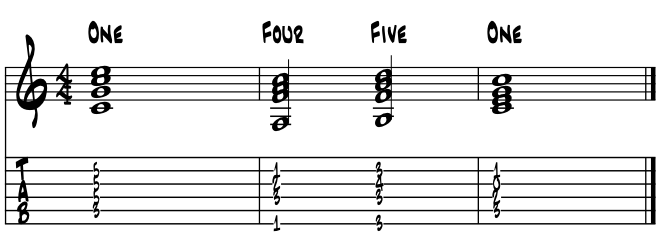

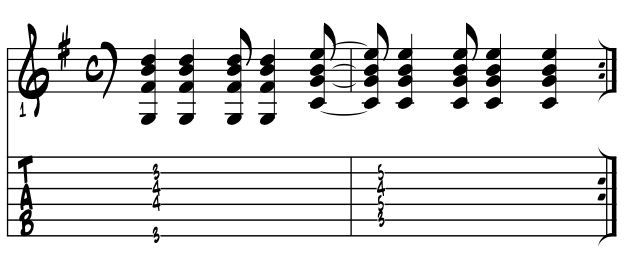

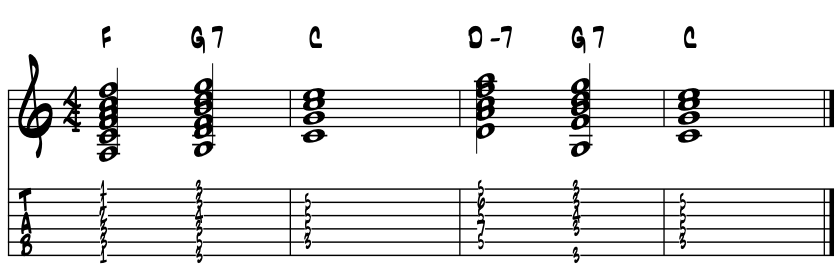

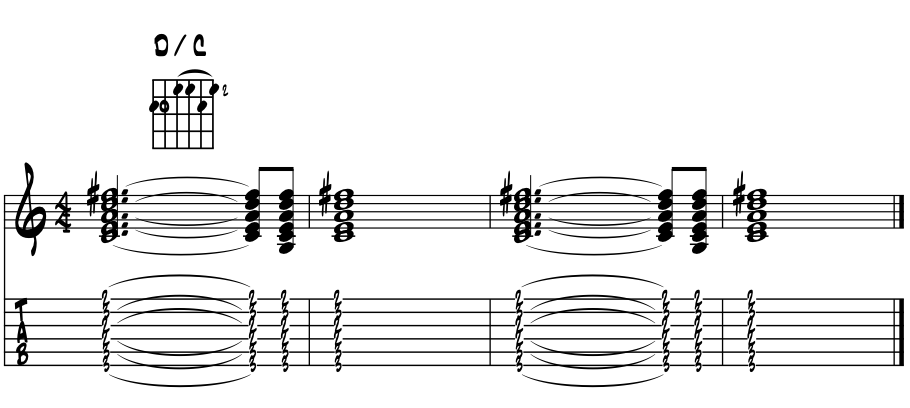

plagal cadence. While the chord built on Four does not get to have its own chord type designation, it does have its own chord cadence. Recognize the following motion in F using two core barre chord shapes? Example 3. |

|

Termed 'plagal', the motion is simply any Four chord to really any One type chord. We'll find this basic back and forth harmonic motion in every style we might imagine. Very popular as a reggae vamp, there's that sense of 'uplift' in the plagal cadence that will generate its own energy to continue forward. Please re-create the following plagal cadences / vamps by ear. Example 3a. |

A perfect authentic cadence. There's this essential idea that we have to unequivocally (without any doubt) establish one pitch as a tonal center and come to a point of 'at rest' in the flow of the music. It comes from the harmony, a chord progression that closes on our chosen tonic pitch, as we create art within one key center. Termed a 'perfect authentic cadence', the Four chord plays the initiating role, setting the direction to the Five chord and then to tonic pitch and chord in play. All chords are root position with the tonic chord having its root note and top note as the tonic pitch. Please examine this resolving cadence. Thinking 'C' major, example 3b. |

|

Sense the motion to resolution?Any doubt as to our tonal destination? Cool, that's the resolute resolution we be after. From this aural bedrock of resolution, we then find ways to imply such stability yet leave some wiggle to what might be coming next. There's a half dozen or so common cadential motions to know of, and those to be created by the modernists among us :) And what if we didn't resolve to One ? What ? We set up all this tonal direction and tension and then not resolve to a resting spot ? Oh well, depending how a story goes, composers will play with expectations yes ... ? What we theorists are often interested in is what creates the degree of aural and emotional confidence in the degree of the sense of resolution. All root position chords help. That our tonic pitch is the top and bottom note of the last chord voicing helps. All of these contribute to a maximum sense of coming home, of being at rest. Perfection. And yet again, we bump into the idea of 'perfect', of perfection, that we've reached the apex of quality in a component, in this case a chord cadence. Our sense of 'perfect' creating the highest standard, which in a perfect authentic cadence is in the finality of chord resolution to our tonic pitch. |

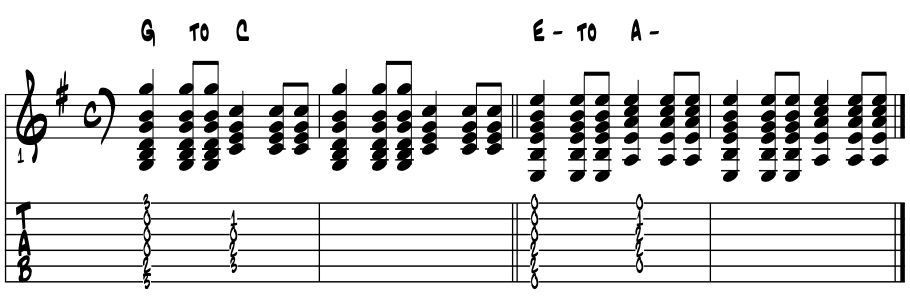

One and Four / major and minor. So thanks to the way we've tuned up our pitches over the last 500 years or so, we get fully functioning One and Four chords in both the relative major and minor tonalities, all within one key center. Let's examine the pitches and spell out the triads for the One and Four chords, here presented in the relative keys of G major and E minor. Example 4. |

G major scale |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

G major arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

One / G major triad |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / C major triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

E minor scale |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

E minor arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

One / E minor triad |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / A minor triad |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

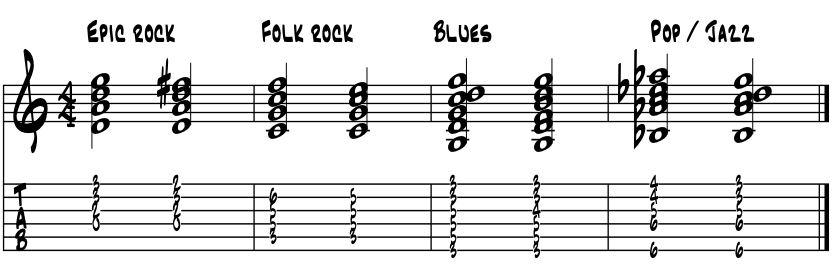

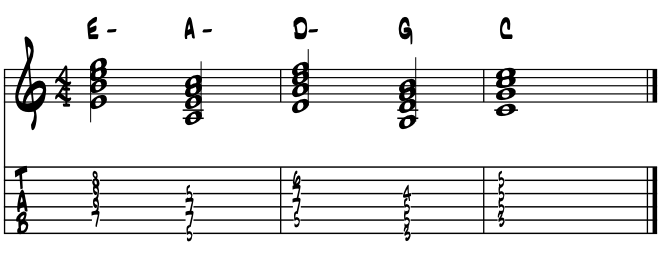

Major and minor One to Four. So from the above charting of the pitches we can see the One and Four chords emerge in both the major and minor tonalities. This in and of itself gives us a lot to work with. Let's create a few of the common chord motions between One and Four, keeping track of musical style, major / minor and using our 'number of pitches philosophy' to generally define a musical style. |

Triads. These next motions using the open triad chords are surely more common throughout the spectrum of styles from children's songs, folk and on into rock and pop. Example 4a. |

|

Ah, the essential motion of One to Four creates so much of the music we love. The core motion of the gospel sounds, easy intros and outs, endless varieties of vamps, probably could rap over these changes, major, minor, bluesy, bossa or jazz, the One to Four motion is not only deep in our collective history but great for dancing too :) |

Add a 7th / minor. We can evolve our triad motion as shown just above by adding a 7th to our chords. In doing so we can add in a bit of the blues hue. Here the theory gets a bit tricky in that we need our 7th to be a blue or minor 7th from our root pitch. Easy do for sure as our pitches are all diatonic. Please examine the spelling of the triad pitches with their diatonic 7th. Example 5. |

E minor |

E |

F# |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

. |

arpeggio |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

. |

|||||||||

One / E minor |

E |

G |

B |

D |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / A minor |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

A |

C |

E |

G |

Using our two essential barre chord shapes, here is the realization of adding the 7th to One and Four in the minor tonality. Example 5a. |

|

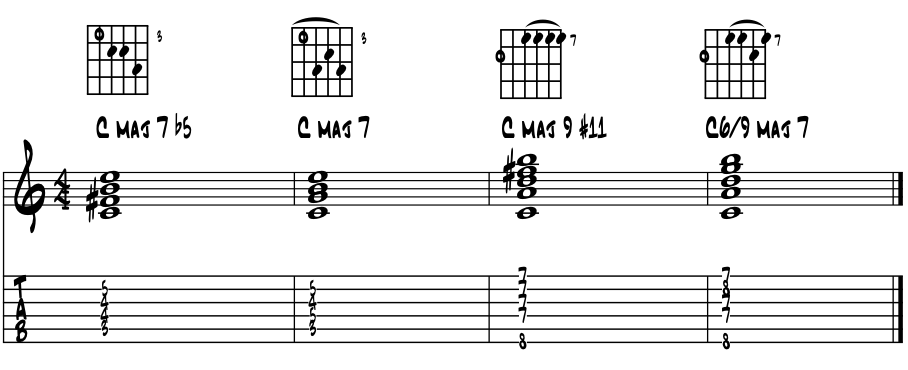

Add a 7th / major. In getting to the blue 7th, we should also look at the diatonic major 7th that our paired relative key centers provide. Cats call this color a 'major 7' chord and while they are found in a more 60's and 70's style pop sounds, moving beyond into bossa and jazz stylings they become simply essential. Please examine the evolution of the triad pitches of One and Four by adding their diatonic 7th's. Example 6. |

G major |

G |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F# |

G |

. |

arpeggio |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

E |

G |

B |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

One / G major |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Four / C major |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

C |

E |

G |

B |

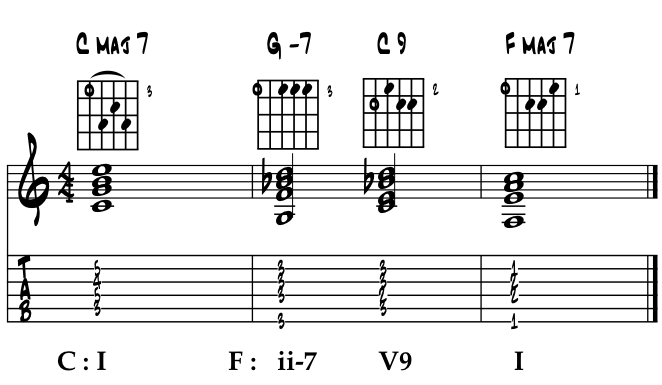

Using essential bossa / jazz chord shapes, dig the motion of One to Four now with colortones. Example 6a. |

|

Surely more of a stiffer 70's pop sound than anything too bossa or jazz. The notation and its playback does have challenges. Oh well, get these shapes under your fingers and make-your-own-ian :) |

'Proper' motion to Four. In this next bit of theory we examine the motion of One moving to Four using the two pitch tritone within V7. In sounding such pitches we are just creating a greater sense of direction of getting to Four. For anytime V7 is involved, we've the potential to direct our musical traffic to resolve to targeted pitches. |

What do we need? So what do we need to properly get to Four? Proper here implies some sort of tension / resolution within a chord. So a tritone interval ? Yep. And what better way to diatonically encapsulate this tension that by placing it within V7. So instead of just chomping from One to Four as in the above ideas, we'll now treat the subdominant as a new key center. |

We can temporarily modulate or change keys when moving from One to Four. In doing this we make available a wide range of possibilities. We do this by adding a new pitch on our palette, a borrowed one from the key we're going to. F major? Yep. Compare the pitches and sounds. Example 7. |

scale degree |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

C major |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

B |

C |

F major |

F |

G |

A |

Bb |

C |

D |

E |

F |

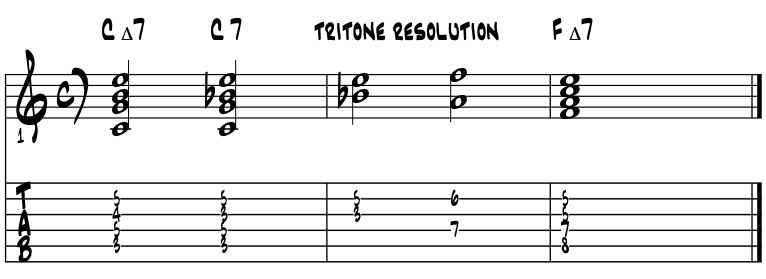

Hmmm ... so our B natural becomes Bb in the key of F major. And if we respell our C chord with added 7th to include the Bb of F major, then our tonic chord becomes a dominant V7 chord; 'C E G Bb.' We use its tension to set up the need to find resolution. Which according these pitches takes us to the key of F major. Please examine these pitches, evolution, sounds and V7 motion to Four. Example 7a. |

|

Cool? This last idea is the 'proper' way we might, in theory, go to Four. Does 'proper' = using a V7 chord to get there? Yes pretty much. Seems like a lot just to get there. Well it is and that's the theory of it. Which once we're in the know of, we're in the know :) |

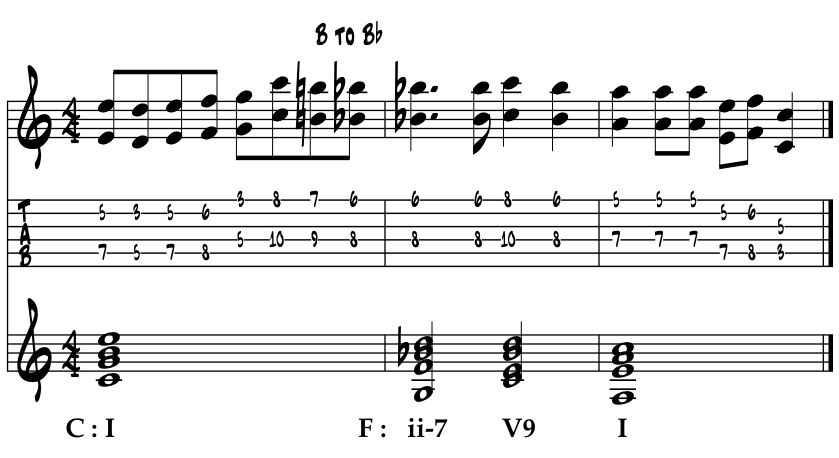

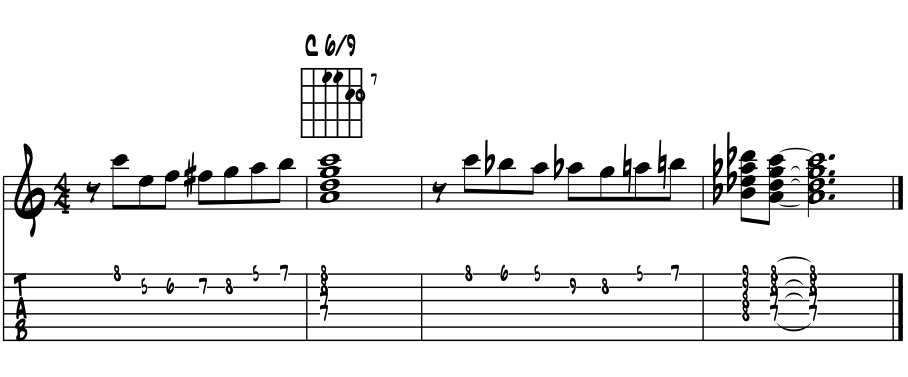

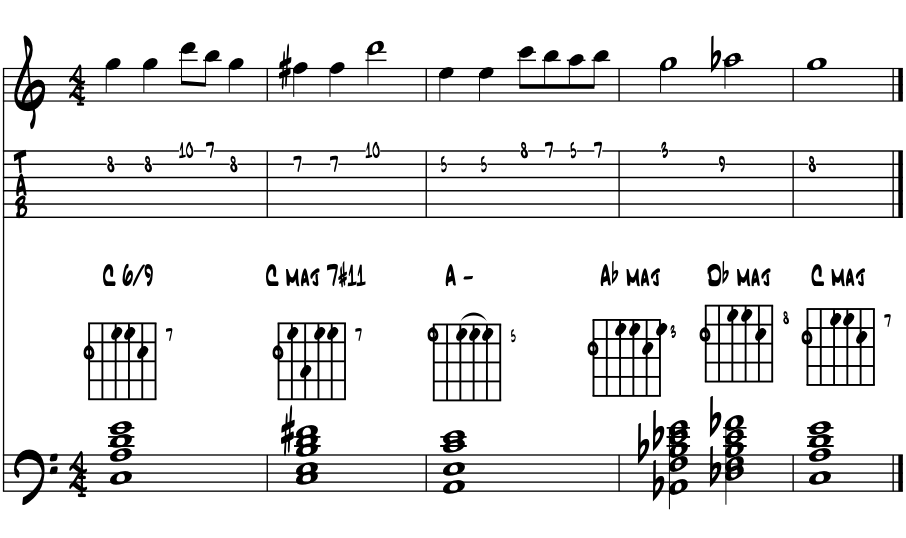

Let's extend this last idea by looking at the transition of the melody pitches and a bit more proper cadential motion by using the Two / Five progression to move to Four. Using a pop style melody line, the pitches of the melody clearly hug the pitches of the chords. The chromatic B to Bb signals the transition keywise from C to F, with octave doubling to add some hip. Example 7b. |

|

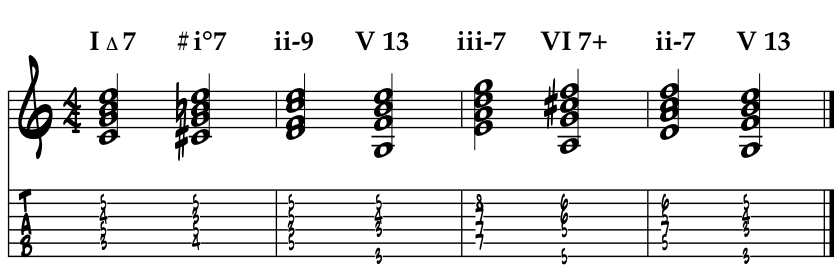

The melody transition in the above idea is a keeper. One of five, these 'transitions' type licks help to clearly direct where the music is going. For in each of the five pitch transitions we generate a tritone bearing V7 chord to direct the music. Here's the above chords in shapes and sounds. For newly emerging jazz cats, these chord shapes together are total butter. Using the Two / Five cadential motion to move from One to Four. Ex. 7c. |

|

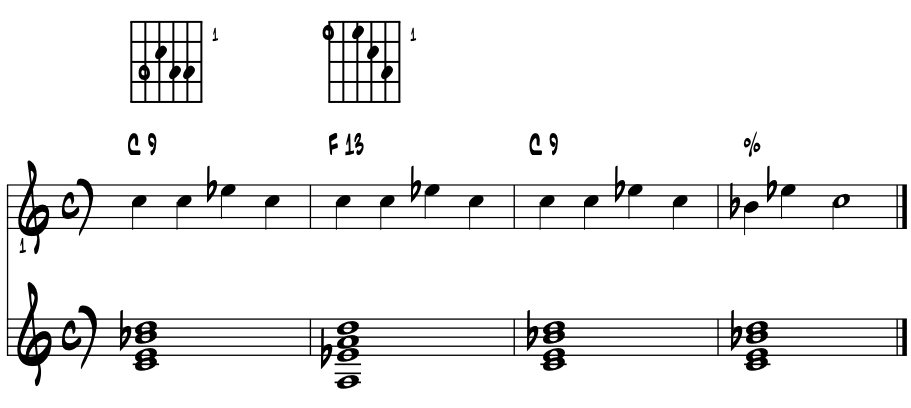

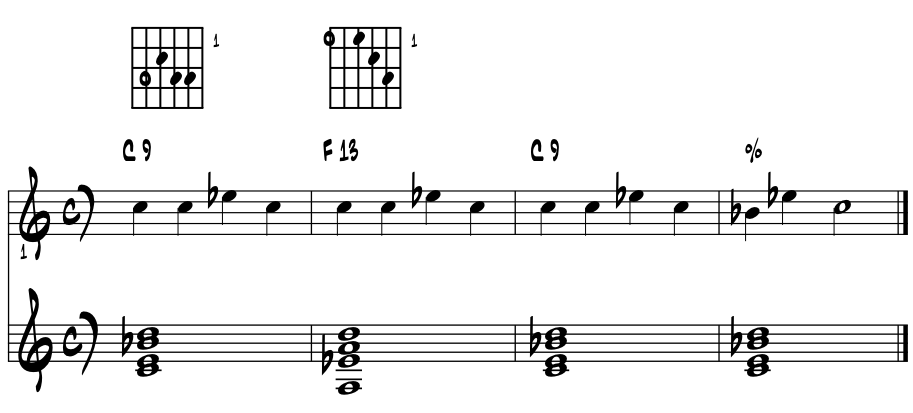

V7 / blues motion to Four. In getting back to the blues and the tonic to subdominant motion in this style, we need V7 chords to make it happen. As we transitioned above keywise from C to F we found C9 and its two pitch tritone interval (maj 3rd and b7) to further energize the sense of forward motion to move. Well, these V7 chords and their need to move are also the core basics of blues harmony. So while our root motion from One to Four is identical, our chords become all V7 / dominant chords. Example 7d. |

|

The last chord shapes and motion are quite common in really any of the blues styles. And us such they make for solid jazz V7 chord shapes too. |

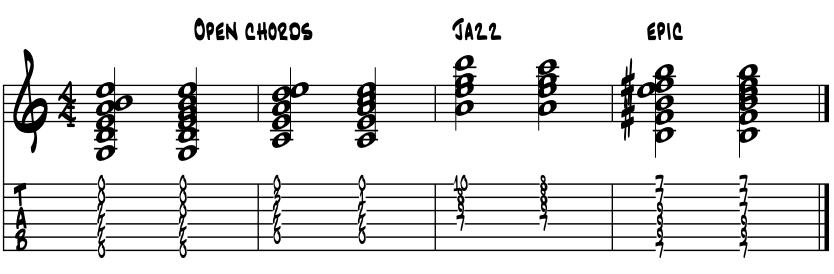

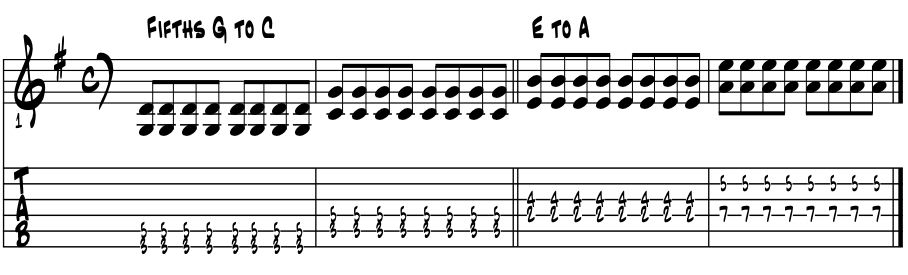

Just the fifths. Dropping the middle pitch of the triads we get the core interval for all of our metallic, shred sounds. The One to Four motion is very common in many of these rock genres. Example 8. |

|

No third ? Then no major / minor distinction of a triad. So we loose the third of the triad and no longer get the major or minor distinction of the pitches. Oh well, we can add that with melody, bass, keys and vocals etc. In today's world of rockin' the house, these plain 'ol perfecto fifths signal process WAY better through the electronical digital / pedals amps and all the newer designed gear of modern today. That said, any of the cool ya find with chords and their progressions, thinking root to root, this 'root ~ fifth' 'old horn' pairing will work just fine ... especially if ya stomp on a something to make the big noise, fill the dance floor, kinda light things ... ya know ? |

The Two / Four evolution revolution. In an above ideas we used the Two / Five motion to move from One to Four. Depending on our musical style and artistic directions, our Four chord easily morphs into Two, becoming a minor 7th ( ii-7 ), with the addition of the root pitch of Two. Please examine the letter names of the diatonic triad built on Four becoming Two, in C major. Example 9. |

F major triad |

becomes |

D - 7th chord |

|||||

F |

A |

C |

D |

F |

A |

C |

|

A stylistic / cadential evolution. As we evolve as players, if we start using Two instead of Four in our cadential motions we're just not in the same Kansas anymore. The sleeker Two chord not only handles the brighter tempos more adroitly but it's proximity to the tonic pitch opens up some wider substitution possibilities for the improvising artist. Compare the two cadences. Example 12a. |

|

Here the subtle difference between the two cadences? The barre chord voicings probably do not best illustrate the idea but are oftentimes a good place to start as their sound is very, very solid in representing the colors. |

So why Two instead of Four? So if you're a jazz leaning theorist, there's no real explanation necessary here as you probably already know just how deeply this cadential motion is woven in the jazz standards. When we get towards the brighter tempos, say 160 and beyond, and get to visit two or three different key centers within one song, we're often glad we have the sleekness of Two. And for those so inclined to venture into our chord substitution possibilities, in combination with brighter tempos and more modulation, this cadential Two / Five / One motion is king. |

|

In our non-jazz styles, the Two chord is often a part of songs that use the cycle of fourths backpedaling root motions or the step wise more gospel sounds when 'stepping' from say One up to Four, or Four down to One; Four, Three, Two, One. Pop artists often love the Two chord, as it's a clear break from the 'three chords and the truth' of One / Four / Five of the blues / rock and roll essential 12 bar form, while still getting us to the same basic places. In evolving '145 into 251' the '3 chord truth' simplicity rolls right over. Look no further than "Just My Imagination" for the power of Two. Penned, recorded and released by the vocal quartet 'The Temptations', in 1971. |

Jazz evolution of Four. We can begin to see the evolutionary influence of transitioning from Four to Two in the American songbook towards the later 30's and into the bebop of the 40's and onward from there. Here, Two paired with Five, together they become a catalyst for getting to points within and beyond the diatonic realm. So while Four has, is and always will be an essential diatonic destination, how we get there, and even 'hint to get there', is a core evolutionary for leaning jazz and a core component of the bop styling. |

From this mid 1940's period onward, jazz music is in general even more modulatory and the sleeker Two / Five root / cadential motion mostly predominates in the various types of modulations. At this point in history we've collectively started on our way to "Giant Steps." |

Coltrane gets a hold of all this and his search begins. From the 50's onward, 2 / 5 motion to the subdominant is very common. Pop arrangers have loved it for many singers, for creating an 'oh ... we went somewhere in the story and thus the music reflects it', while remaining within the same key center. For indeed by chord and pitch by pitch, interval by interval, the diatonic One and Four are perfectly identical to one another until ... |

Essential jazz standards such as "Misty" and "Here's That Rainy Day", written in this 1950's period follow this scheme. As these were the 'pop songs' on American radio in their day. Remember that in every music globally; the folk, blues, rock and pop and their endless subgenres, the subdominant Four will always be an essential musical destination, a starter for the motor and the way to bring some gospel with a flick of the wrist. |

|

Passing diminished chord. Known here in Essentials as the great 'accelerator', in working with Two we immediately gain the possibility of slipping in a diminished chord between tonic One and Two. While surely a jazz harmonic motion, historically it's important and there's some nice potential energy in these changes. Diminished acceleration 101. Example 12b. |

|

Rhythm changes. These last four bars are one version of what we often call rhythm changes. They come from the 1930 hit song by George and Ira Gershwin simply titled "I Got Rhythm." Anything but simple really, the above idea is a cycle of chords, that when twice repeated, become the eight bar A section of our 32 bar song form. A mainstay for jazz improvisors, the passing diminished chord on the second half of the first bar, helps get things cookin' right out the gate. |

|

So is Four eliminated in this art? No, not at all. Even in the most advanced of the writing, motion to the subdominant Four is nearly always present, and can always retain its essential gospel, its secondary tonic appeal and create its glowing sense of gladness of heart and be a numero uno spirit lifter. And when there's no motion to Four in a song ? It certainly has its own vibe. |

In between, we'll often see the Two chord jet setting around the circle of fifths, setting up the dominant chord to traffic cop the direction of the music. It is really all good because in the American fabric of life and its music, all can find a spot to contribute, to be a part of a bigger thing, to help our collective stories get told. |

Subdominant chord in the minor tonality. Our theory name for our diatonic fourth scale degree in both major and minor keys is 'subdominant.' The diatonic core of our Four chord in the minor tonality is a minor triad. Defaulting to our root pitch of 'A' and the diatonic natural minor grouping of pitches, examine the letter names as we extract its Four chord. Example 13. |

|

By now easy do yes? OK with the spelling of chords? How our scales become arpeggios and arpeggios become chords? Cool. If not, I'll be honored to be the one to hip you to these changes ... follow these three links :) |

A too cool motion by far. While much has gone over to Four so far, this loop in the minor starts on Four and finds its way to back to One. Thinking A minor in a reggae feel, three chords and the truth. Example 13a. |

|

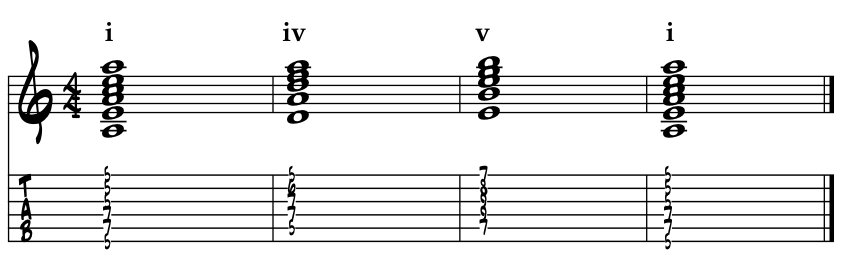

One / Four / Five. This next idea is simply the chord progression One / Four / Five / One using diatonic triads in the key of A minor. Any three chord minor blues will be based along these changes. Classic Americana songs such as "Let My People Go" are based around these three chords. Jazz guitar wizard Mark Whitfield covered this a while back. What follows here are just straight, powerful 1960's styled barre chords. Example 13b. |

|

|

The minor 9. One very powerful emotional color is created by adding in the 9th to the minor 7 chord. When we use this color when moving to Four, good things can happen. The following voicings are very common in many styles of playing. Oh, and the minor nice shape used here is a very adaptable one to all sorts of Latin / bossa guitar. First we'll spell out the chords. Ex. 13c. |

scale degrees |

root |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

. |

. |

minor scale formula |

. |

1 |

1 / 2 |

1 |

1 |

1 / 2 |

1 |

1 |

. |

. |

A minor scale |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

A |

A |

B |

arpeggio degrees |

root |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

15 |

. |

. |

A minor arpeggio |

A |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F |

A |

C |

E |

A - 7 |

A |

C |

E |

G |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

arpeggio degrees |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

D - 9 |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

D |

F |

A |

C |

E |

|

Try the above shapes as a vamp with your band. Just jam back and forth and see what shakes loose. It'll work in all sorts of grooves and styles, especially if you play for the dancers :) Works great in reggae and Latin grooves. And I'll bet U $100 bucks, if you record the session, your band will write a song from it. |

|

Perfect fourths / Quartile harmony. Bending off track a bit here, dig this next essential coolness. |

|

The chord in the last measure above is a combination of one major 3rd and the stacked 4th's. Thirds of course are the building blocks of the way more common tertian harmony. Stacking fourth's we call quartile. And while nearly all of our American styles use tertian harmony, we'll find the quartile chords in some very consistent spots through all of the styles. |

Perhaps the most common spot we'd find a quartile harmony would be as the 'final hold', more commonly known as the last chord of an arrangement. For us guitarists, their sound is very tight and bright. We'll hear it of course in jazz, but also country swing and some pop. Cat's like rockabilly monster Brian Setzer will often close a swinging, bluesy rockin' 2 and 4, 12 bar number with a quartile color. When we need a super bright, not too vanilla tonic chord color, with the key center's tonic pitch in the lead, quartile voiced chords can win the day just about every time. Example 14a. |

|

|

Two common endings. The two ideas above are perhaps as cliche an ending as we have in the Americana, jazz it up, rockabilly songbook. There's endless variations and capping the line with 6 / 9 ends the tune brightly. That half step lead in from above in the last measure is often played as what we term a slur. Simply strike the chord and slide it down by half step. |

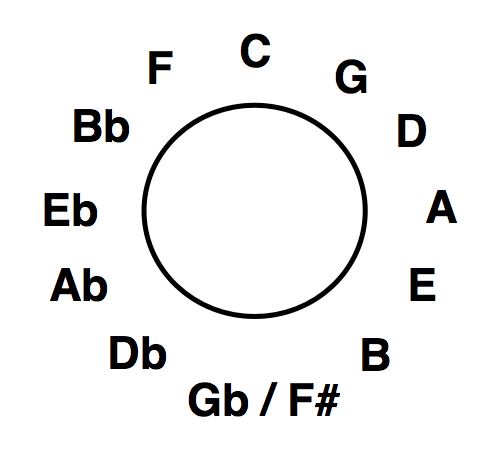

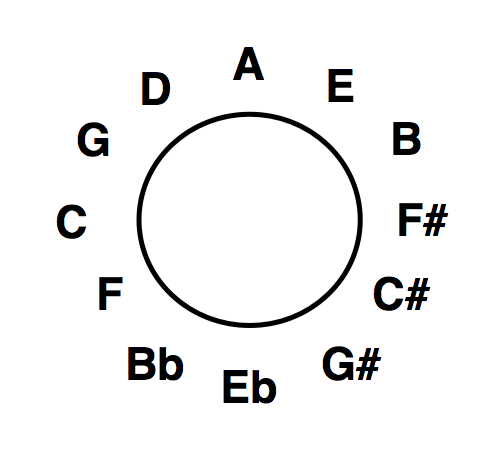

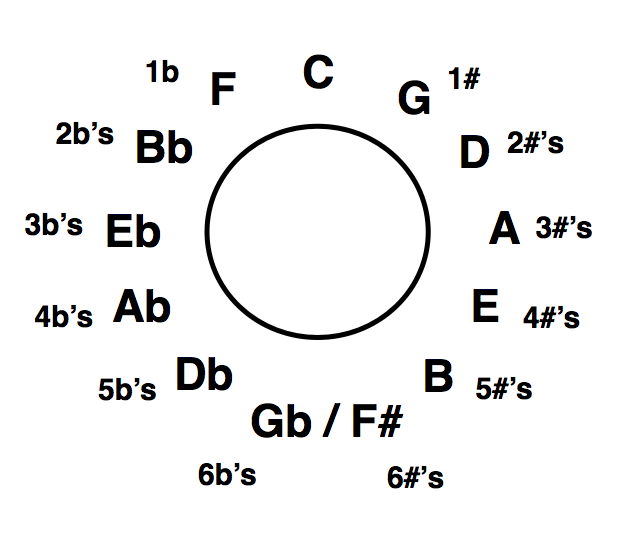

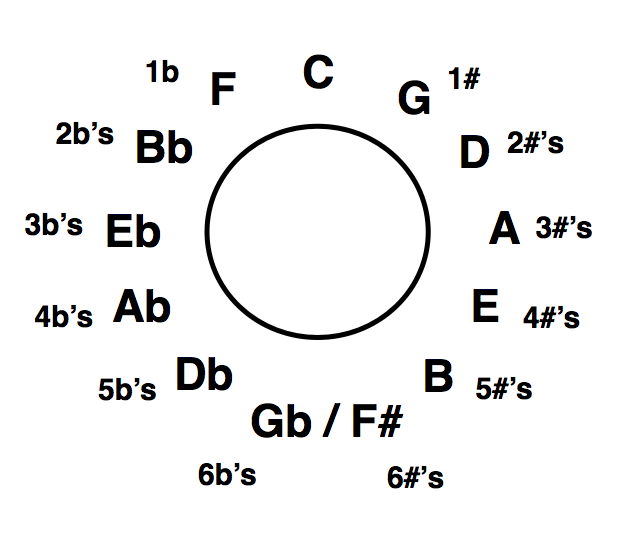

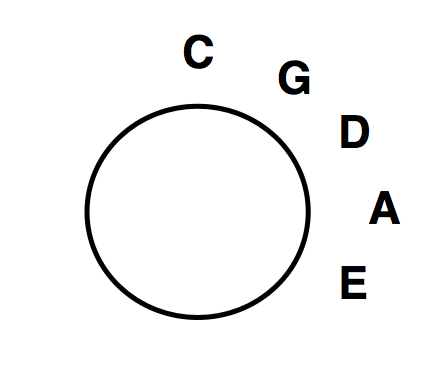

Backpedaling. While we're stacking and thinking of cool musical things in fourths, we should examine our keyclock and discuss the idea of backpedaling. While we generally associate the term with riding bicycles, as we spin our pedals backwards to coast a bit. In our music studies we do the same thing, as we backpedal our letter named pitches back towards the 12 o'clock position of our cycle of fifths. In these examples, the relatives C major and A natural minor top the charts at the 12:00 positions. This depiction is global now. Example 15. |

arranged by major keys |

arranged by minor keys |

|

|

clockwise = 5th's |

counterclockwise = 4th's |

Have to start somewhere. This closed circle symbolically represents the unbreakable looping perfection of our pitches. We use the accidentals, the flats and sharps, to properly execute our diatonic scale formula for each of our 12 key centers. Whichever will be easiest to notate and easiest to read wins the day. |

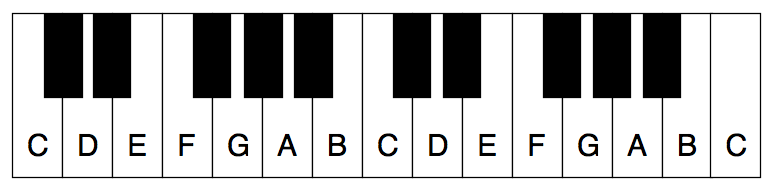

So why are C major and A minor at the top of our key clocks? Because in our system of music, their groups of pitches contain no accidentals. So on a piano, these key centers are created by just the white keys. Quick rote review. The letter name at the top of the circles represents our starting point as its key signature and pitches use no sharps or flats, just the white keys on the piano. The letter name / pitch A at the top of the minor keys illustration becomes our starting point, as the pitches of A natural minor are also just the white keys on the piano. Same with C major. Thus, yet another way to look at the major / minor / Yin / Yang magics of the system and organization of our musical resources. |

Piano white keys. Here's an illustration of the white keys of our piano and their letter names. Do note the 'two / three' repeating pattern of the black keys. And do also note where there is no black key in between two sets of white keys. For these are the 'built right in', naturally located half step intervals that build up these two groups. Example 15a. |

|

|

Natural half steps. In the above keyboard illustration we note that there is no black key between the two pitches E and F and between the two pitches B and C. For we guitarists, these are two half step intervals, so one fret. Historically, we had these pitches and half step locations long before we had keyboards. |

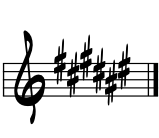

Clockwise / 5th's. Thinking major keys, we move clockwise to the right and the intervals between our letter names is the perfect 5th. This puts us in the 'sharp keys' territory of our keyclock. With each clockwise hourly click, we pick up another sharp as we move through our keys. Thus from the illustration which follows, G major will have one sharp, D major will have two sharps and so forth around. Example 15b. |

the sharp keys are clockwise |

|

Sharp key signatures. Here are the sharp key signatures for our major / relative minor key centers. Example 15c. |

G major |

D major |

A major |

E major |

B major |

F# major |

|

|

|

|

|

|

E minor |

B minor |

F# minor |

C# minor |

G# minor |

D# minor |

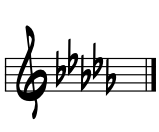

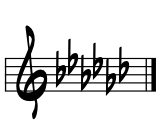

Counterclockwise / 4th's. Reversing our direction to the left or counterclockwise, we encounter our 'flat keys.' Example 15d. |

the flat keys are counterclockwise |

|

Flat key signatures. Here are the flat key signatures for our major / relative minor key centers. Example 15e. |

F major |

Bb major |

Eb major |

Ab major |

Db major |

Gb major |

|

|

|

|

|

|

D minor |

B minor |

F# minor |

C# minor |

G# minor |

D# minor |

Cool so far. A bit of a digression perhaps from the immediate topic at hand. But all of our theory roads do eventually lead to that proverbial Rome, which in its day was the modern Mt. Parnassus, all of toga fashion fame. |

Back to backpedaling. So with the above ideas in mind, all we're doing when we backpedal is simply working our way back towards a predetermined point within the cycle. In most cases when we find this in our songs, we're simply moving by perfect fourth back to our tonic pitch, the key center of the song. Examine this bit of an incomplete circle of pitches which follows, thinking diatonically in the key of C major. Example 15f. |

|

|

Cool so far? So we can see and hear from the above illustrations how our chord cycle is backpedaling, or moving counterclockwise, to our tonic pitch C. Can you sense the direction of the motion of the chords? That's tonal gravity. And can you sense where it's going to land (resolve)? That's aural predictability. |

While most of our American music uses less root notes in regards to the number of pitches we backpedal, the last idea common throughout. That jazz cats do this all the time, often also adding color tones to triads and even chord substitutions along the way ... to as they say ... jazz things up a bit :) |

Chord progressions. The above harmonic motion is of course a famous jazz chord progression we commonly termed a Three / Six / Two / Five / One. We simply backpedaled from Three, by the interval of a perfect fourth, to get to One. This type of motion is not only a very very common way to create a sequence, it is one of music's strongest foundational components, spanning styles and cultures through centuries of songs. Dr. Miller often quipped about chord progressions of the jazz standard songs from the 30's through the 50's that we learned at school,"that if it's not root motion by fourth, it's probably by half step." |

Our earlier Baroque brethren always loved a good sequence. So not only is our circle of 4th's / 5th's a way to arrange our keys but it can also illustrate pathways back towards our starting point. It's a good way to organize our shedding and keep track of things, all depending of course on one's own art / resource needs. |

|

The whole tamale. In completing this discussion of backpedaling for now, this next idea starts and ends on the pitch C. In between we rapidly visit all of our remaining eleven pitches via the counter - clockwise, backpedaling interval of our perfect 4th. Example 15g. |

|

Off to Rodney. Wow, well that didn't take long did it. All we did was a mix'em-upian modal style octave transpositional approach to the backpedaling cycle of our 12 pitches, brighten the tempo a bit and the next thing ya know ... we're just not in Kansas anymore. We simply moved from our diatonic 'inside' to 'outside' in a rather rapid way. Hey ... somebody harmonize this line! |

So needless to say, the rather harmless look and nature of our cycle of 5th's illustration contains a bit more than potentially meets the eye. Just might be about what we each bring to the conversation. For emerging jazz cats hunting new tunes, Jerome Kern's "All The Things You Are" from 1939 vintage is not only a solid standard song but a backpedaling extravaganza ta boot ! |

|

The 'sus 4' chord. Calling all pinball wizards ... start you're B sus chords! The sus 4 chord is a such solid component of so much rocking coolness. Of course the reference above is to The Who's epic "Tommy." Their song "Pinball Wizard", oh and "Help" by the Beatles, are two classic imports that all start strongly with sus 4 chord. West Coast legends Van Halen's "Jump" uses the same 'sus 4' colors to get their roar roaring. |

|

This epic 'sus 4' sound should find a home somewhere on everyone's palette, as we can use it in nearly all of our styles somewhere. That it's just too easy to create and rocks too hard to not to. To create the sus 4, find the major or minor third in any chord and raise it to its diatonic fourth. Here are various common major chord shapes morphed into their 'sus 4' mode. Example 16. |

Recognize some of those sounds? Cat's in power trio formats like Eddie Van Halen, The Edge, Jimmy Page, often use these sus colors to suspend the major / minor sound and suspending the sense of time in the music, giving a cat a chance to catch their breath so to speak, before rocking onward. These next few shapes work the sus 4 colors in the minor tonality. Example 16a. |

Sus - ing our pitches. Here are the letter pitches of the above chords and their 'sus 4' morphing. Example 16b. |

|

Cool ? yea 'sus 4' is all about raising the 3rd, thus the major / minor character of the triad goes away. |

The 'sus 4' in open G. In the open G tuning, the earlier holdover of the four and five string banjo onto the six string guitar, the 'sus 4' color is right under the fingers as a one pitch addition to the index finger bar. For those readers who want to rock on out ... this color is surely a common and cool way to get there. |

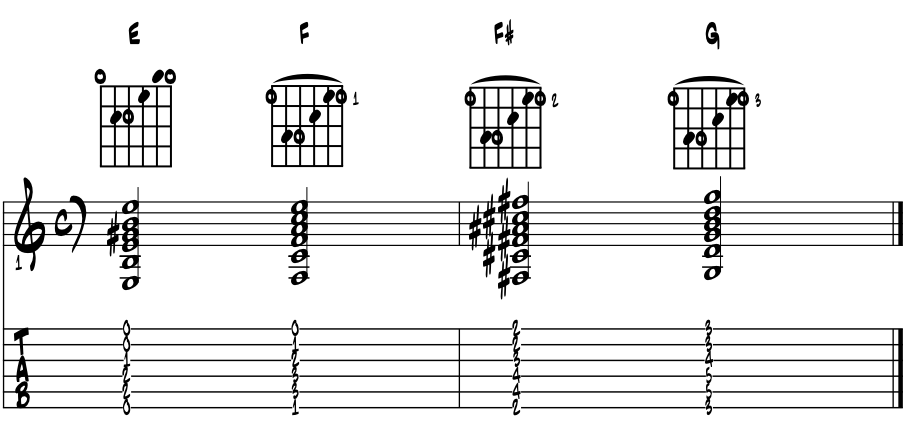

Barre chords. The changes used in the last idea are based on the core open E to movable barre shape. The idea that by learning one shape we get lots of chords of different roots, keys etc., simply by moving the same shape up and down the neck. Let's take a moment to project this core evolutionary concept in regards to putting our theory knowledge into practice. |

One becomes many. The idea here is that one barre chord shape could become many different named chords simply by changing its root pitch. Cats call this a movable form. As this idea applies to other aspects of our theory as well, this a perfect spot in the discussion to get hip if need be. Example 17. |

Easy enough eh? Surely run the shape as best you can and rote memorize the letter names of the root pitches on the low E string. Movable forms makes it all seem a bit easier n'est-ce pas? |

In theory. That our chord progressions can be evolved from a series of letter names into numerals, facilitating their projection from each of our 12 pitches, begs for barre chords. So in movable forms, any of our musical components can be projected from each of our twelve pitches, advancing our artistic resources. |

Advanced theory. Another way of understanding the resources is by categorizing like objects into groups that function in the same musical capacities. Understanding things in this way can accelerate our learning process by allowing us to group like functioning elements into definable sets or categories. Examples of this way of thinking would be viewing our harmony by chord type, or learning the musical form of the songs we play, thinking of a key center as a 'movable One', or understanding the subdivision of our rhythmic note values. |

So as you go through the theory and discover these theoretical 'shorthand' possibilities, reflect a moment on them and decide how important they might be to the music you dream to create. And if there is some potential there, then by all means dig in, master the principle and run it up and down the neck to get some of it under your fingers. Once there's a trace, it'll evolve over time and as artistic needs are met. |

For so much of creating well crafted art can be about perspective. And perspective can include a reordering of our resources, based on the core commonality of the elements. For oftentimes we can modernize our own work simply by the re-juxtaposition of elements. |

So in essence, by understanding the core theory commonalities of like functioning elements, new combinations, patterns and our ability to balance them into new and potentially exciting art, can evolve by our own gumption and creative process. This is the empowerment potential of understanding the Essentials. |

Lydian mode. Upon the fourth degree of our diatonic major / minor scale we can locate the Lydian mode. As one of four original ancient Greek modes, carried through our history evolution of the pitches, Lydian songs herald triumph. Essentially a diatonic major scale with an augmented or raised fourth scale degree, today we'll find this distinctive color in the jazz styles, as it becomes a portal to the polytonal and when 'corrected', the essential basis for evolution to the #15 portal. |

Lydian's whole tone aural quality is created by its initial three whole step interval formula which really sets it apart, makes it unique. These whole steps create a tritone interval ( three tones ) between root and the augmented 4th as depicted in the chart. Please examine the pitches and formulas as we extract F Lydian from its parent scale of C major. Example 18. |

|

Transposing our pitches. Now that we have located our Lydian pitches from within our diatonic major / minor parent core, let's project or transpose it to our common theory root pitch to create C Lydian, then compare the pitches to C major and then examine the results. Example 18a. |

|

All in the one pitch? Yep, the Lydian distinction all centers on it's raised 4th degree, which in its arpeggio form becomes the #11chordal colortone. Otherwise these groups are identical; One and Four. |

Lydian melody / harmony. Mostly a jazz color in Americana musics, the Lydian colors become yet another way to shape our tension / release dynamic. There are two reasonably common tonic function chords with Lydian characteristics. Lydian then to Ionian. Example 18b. |

# 4 / b 5. The F# in the first bar probably should be written as Gb, just didn't want to confuse things here from the chart, as the sound is of course the same. The tonic major 7 b5 simply creates a bit of tension that is released in bar two. |

Same idea with the #11 chord in bar 3, here we've simply moved the #4 up an octave and filled in the diatonic tonic color tones underneath. In both cases there's a major 3rd in the chords and the #4 resolves to 5th of C major. So an upward resolving tension or suspension? Yep. |

Rule of thumb. When numerically identifying our color tones, we should at least in theory include all of the pitches that 'properly' support it. Thus the #11 has its major triad and 7th and 9th underneath supporting. Ideally we would include them in our #11 voicings. Piano players often do. Please examine the pitches and numbers. Example 18c. |

arpeggio degrees |

root / 1 |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

#11 |

13 |

15 |

C Lydian pitches |

C |

E |

G |

B |

D |

F# |

A |

C |

So we notate things as best we can, learn our parts and hopefully get to rehearse the music in a professional manner. Things surely change under the lights and our ability to stay focused and concentrate is a big part of the performing success. |

In this next trending Lydian melodic idea, we broadly support the line's #4 / #11 of bar 2 with C major 7/9. Example 18d. |

|

An interesting and quite modern Lydian sequence between our essential core major / minor tonal centers. |

Polytonality. Another common spot for the Lydian #4 / #11 pitch is in creating a sense of two tonal key centers simultaneously, i.e., polytonality. In this next idea we simply create an open D major triad over part of a C major chord to support our melody line. Example 18e. |

|

It's a fine line. Pretty rich sound yes? This chord shape makes for a nice bossa feel with the root / Five bass motion. In all of this Lydian analysis there's often a few ways to look at the pitches. Are they polytonal, a #11 chord, Five of Five in third inversion etc. As modernists, we need to strive to understand the sounds, eventually recognize them by ear them and label them accordingly. Thinking from the root keeps things sorted out. |

Review. Well after all this discussion, needless to say just how important Four is in the American sounds. That 8 out of 10 tunes in the Americana songbook include some kind of Four chord. In every style and genre, vamp and progression, Four or some derivation thereof, is helping to create and work the magic. Cool? So, next by half step to #4 yes? Yes indeed. |

"It is not so hard for me to jam." |

wiki ~ MC Hammer (attributed to ?) |

Review. References for this page's information comes from school, books and the bandstand and made way easier by the folks along the way. |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References. References for this page come from the included bibliography from formal music schools and the bandstand, made way easier by the folks along the way. In addition, books of classical literature; from Homer, Stendahl and Laudurie to Rand, Walker and Morrison and of today, provided additional life puzzle pieces to the musical ones, to shape the 'art' page and discussions of this book. Special thanks to PSUC musicology professor Dr. Y. Guibbory, who 40 years ago provided the initial insights of weaving the history of all the fine arts into one colossal story telling of the evolution of AmerAftroEurolatin musical arts. And to teacher-ed training master, Dr. Joyce Honeychurch of UAA, whose new ideas of education come to fruition in an e-book. |

"Life is about creating yourself." |

wiki ~ Bob Dylan |

Find an e-book mentor. Always good to have a mentor when learning about things new to us. And with music and its magics, nice to have a friend or two ask questions and collaborate with. Seek and ye shall find. Local high schools, libraries, friends and family, musicians in your home town ... just ask around, someone will know someone who knows someone about music who can help you with your studies of the musical arts with this e-book. |

Intensive tutoring. Luckily for musical artists like us, the learning dip of the 'covid years' can vanish quickly with intensive tutoring. For all disciplines; including all the sciences and the 'hands on' trade schools, that with tutoring, learning blossoms to 'catch us up.' In music ? The 'theory' of making musical art is built with just the 12 unique pitches, so easy to master with mentorship. And in 'practice ?' Luckily old school, the foundation that 'all responsibility for self betterment is ours alone.' Which in music, and same for all the arts, means to do what we really love to do ... to make music :) |

|

"These books, and your capacity to understand them, are just the same in all places. Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed, is more important than any other one thing." |

|

Academia references of Alaska. And when you need university level answers to your questions and musings, and especially if you are considering a career in music and looking to continue your formal studies, begin to e-reach out to the Alaska University Music Campus communities and begin a dialogue with some of Alaska's finest resident maestros ! |

|

Formal academia references near your home. Let your fingers do the clicking to search and find the formal music academies in your own locale. |

"Who is responsible for your education ... ? |

'We energize our learning in life through natural curiosity and exploration, and in doing so, create our own pathways of discovery.' Comments or questions ? |